Taurotragus

Taurotragus is a genus of large antelopes of the African savanna, commonly known as elands. It contains two species: the common eland T. oryx and the giant eland T. derbianus.

| Eland | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Taurotragus oryx | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Tribe: | Tragelaphini |

| Genus: | Taurotragus Wagner, 1855 |

| Type species | |

| Antilope oreas Pallas, 1777 | |

| Species | |

| |

Taxonomy

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships of the Taurotragus species in relation to the species from a paraphyletic Tragelaphus. From combined analysis of all molecular data (Willows-Munro et.al. 2005) |

Taurotragus is a genus of large African antelopes, placed under the subfamily Bovinae and family Bovidae. The genus authority is the German zoologist Johann Andreas Wagner, who first mentioned it in the journal Die Säugthiere in Abbildungen nach der Natur, mit Beschreibungen in 1855.[1] The name is composed of two Greek words: Taurus or Tauros, meaning a bull or bullock;[2][3] and Tragos, meaning a male goat, in reference to the tuft of hair that grows in the eland's ear which resembles a goat's beard.[4]

The genus consists of two species:[1]

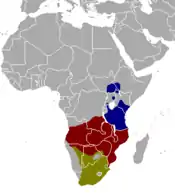

| Species | Subspecies | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Common eland (Taurotragus oryx) (Pallas, 1766)

|

Three subspecies of common eland are recognized, though their validity has been in dispute.[5][6]

|

|

| Giant eland (Taurotragus derbianus) (Gray, 1847)

|

The largest antelope in the world. It has two subspecies:[7]

|

|

Taurotragus is sometimes considered part of the genus Tragelaphus on the basis of molecular phylogenetics. Together with the bongo, giant eland and common eland are the only antelopes in the tribe Tragelaphini (consisting of Taurotragus and Tragelaphus) to be given a generic name other than Tragelaphus.[8] Although some authors, like Theodor Haltenorth, regarded the giant eland as conspecific with the common eland, they are generally considered two distinct species.[9]

Genetics and evolution

The eland have 31 male chromosomes and 32 female chromosomes. In a 2008 phylogenomic study of spiral-horned antelopes, chromosomal similarities were observed between cattle (Bos taurus) and eight species of spiral-horned antelopes, namely: nyala (Tragelaphus angasii), lesser kudu (T. imberbis), bongo (T. eurycerus), bushbuck (T. scriptus), greater kudu (T. strepsiceros), sitatunga (T. spekei), giant eland and common eland. It was found that chromosomes involved in centric fusions in these species used a complete set of cattle painting probes generated by laser microdissection. The study confirmed the presence of the chromosome translocation known as Robertsonian translocation (1;29), a widespread evolutionary marker common to all known tragelaphid species.[10]

An accidental mating between a male giant eland and a female kudu produced a male offspring, but it was azoospermic. Analysis showed that it completely lacked germ cells, which produce gametes. Still, the hybrid had a strong male scent and exhibited male behaviour. Chromosomal examination showed that chromosomes 1, 3, 5, 9, and 11 differed from the parental karyotypes. Notable mixed inherited traits were pointed ears as the eland's, but a bit widened like kudu's. The tail was half the length of that of an eland, with a terminal tuft of hair as in kudu.[11] Female elands can also act as surrogates for bongos.[8]

The bovid ancestors of the eland evolved approximately 20 million years ago in Africa; fossils are found throughout Africa and France but the best record appears in sub-Saharan Africa. The first members of the tribe Tragelaphini appear 6 million years in the past during the late Miocene. An extinct ancestor of the common eland (Taurotragus arkelli) appears in the Pleistocene in northern Tanzania and the first T. oryx fossil appears in the Holocene in Algeria.[8] Previous genetic studies of African savanna ungulates revealed the presence of a long-standing Pleistocene refugium in eastern and southern Africa, which also includes the giant eland. The common eland and giant eland have been estimated to have diverged about 1.6 million years ago.[12]

Differences between species

Both the species of eland are large spiral-horned antelopes. Though the giant eland broadly overlaps in size with the common eland, the former is somewhat larger on average than the latter. In fact, the giant eland is the largest species of antelope in the world.[13][14][15][16] Eland are sexually dimorphic, as the females are smaller than males. The two eland species are nearly similar in height, ranging from 130–180 cm (51–71 in).[17] In both species, males typically weigh 400 to 1,000 kg (880 to 2,200 lb) while females weigh 300 to 600 kg (660 to 1,320 lb).[17][18]

The coat of the common eland is tan for females, and darker with a bluish tinge for males.[19] The giant eland is reddish-brown to chestnut. The coat of the common eland varies geographically; the eland in southern Africa lack the distinctive markings (torso stripes, markings on legs, dark garters and a spinal crest) present in those from the northern half of the continent. Similarly, the giant eland displays 8 to 12 well-defined vertical white torso stripes. In both species the coat of the males darken with age. According to zoologist Jakob Bro-Jørgensen, the colour of the male's coat can reflect the levels of androgen, a male hormone, which is highest during rutting.[20]

References

- Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M., eds. (2005). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- "Taurus". Encyclopædia Britannica. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Harper, Douglas. "Taurus". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- "Tragos". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 696–7. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Skinner, JD; Chimimba, CT (2005). "Ruminantia". The Mammals of the Southern African Subregion (3rd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 637–9. ISBN 0-521-84418-5.

- Hildyard, A (2001). "Eland". In Anne Hildyard (ed.). Endangered wildlife and plants of the world. Marshall Cavendish. pp. 501–503. ISBN 0-7614-7198-7.

- Pappas, L. A.; Anderson, Elaine; Marnelli, Lui; Hayssen, Virginia (2002). "Taurotragus oryx" (PDF). Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists. 689: 1–5. doi:10.1644/1545-1410(2002)689<0001:TO>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2011.

- Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Artiodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Rubes, J; Kubickova, S; Pagacova, E; Cernohorska, H; Di Berardino, D; Antoninova, M; Vahala, J; Robinson, TJ (2008). "Phylogenomic study of spiral-horned antelope by cross-species chromosome painting". Chromosome Research. 16 (7): 935–947. doi:10.1007/s10577-008-1250-6. PMID 18704723. S2CID 23066105.

- Jorge, W; Butler, S; Benirschke, K (1976). "Studies on a male eland X kudu hybrid". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 46 (1): 13–16. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0460013. PMID 944778.

- Lorenzen, Eline D.; Masembe, Charles; Arctander, Peter; Siegismund, Hans R. (2010). "A long-standing Pleistocene refugium in southern Africa and a mosaic of refugia in East Africa: insights from mtDNA and the common eland antelope". Journal of Biogeography. 37 (3): 571–581. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2009.02207.x.

- "Ecology". Czech University of Life Sciences. Giant eland conservation. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Prothero, Donald R.; Schoch, Robert M. (2002). "Hollow horns". Horns, tusks, and flippers : the evolution of hoofed mammals. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-8018-7135-2.

- Lill, Dawid van (2004). Van Lill's South African miscellany. Zebra Press. p. 4. ISBN 1-86872-921-4.

- Carwardine, Mark (2008). "Artiodactyl". Animal Records. Sterling. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4027-5623-8.

- Atlan, B. "Taurotragus derbianus". University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Kingdon, J (1997). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11692-X.

- Estes, RD (1999). "Bushbuck Tribe". The Safari Companion: A Guide to Watching African Mammals, Including Hoofed Mammals, Carnivores, and Primates. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 154. ISBN 0-9583223-3-3.

- "Biological characteristics". Czech University of Life Sciences. Giant eland conservation. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

_3_crop.jpg.webp)