1932 United States presidential election

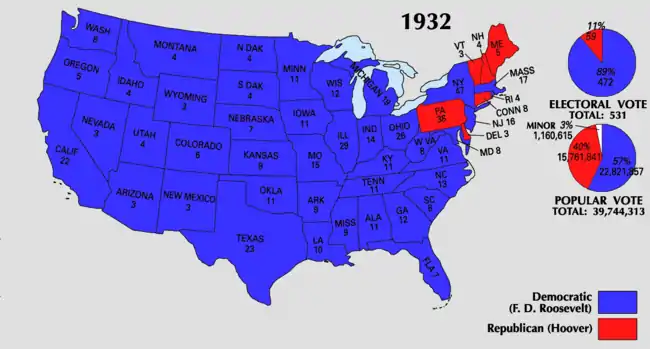

The 1932 United States presidential election was the 37th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 1932. The election took place against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Incumbent Republican President Herbert Hoover was defeated in a landslide by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Governor of New York and the vice presidential nominee of the 1920 presidential election. Roosevelt was the first Democrat in 80 years to win an outright majority in the popular and electoral votes, the last one being Franklin Pierce in 1852. Hoover was the last elected incumbent president to lose reelection until Jimmy Carter lost 48 years later. The election marked the effective end of the Fourth Party System, which had been dominated by Republicans.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

531 members of the Electoral College 266 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 52.6%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

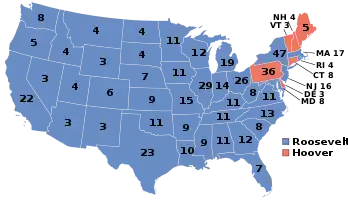

Presidential election results map. Blue denotes those won by Roosevelt/Garner, red denotes states won by Hoover/Curtis. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Despite poor economic conditions due to the Great Depression, Hoover faced little opposition at the 1932 Republican National Convention. Roosevelt was widely considered the front-runner at the start of the 1932 Democratic National Convention, but was not able to clinch the nomination until the fourth ballot of the convention. The Democratic convention chose a leading Southern Democrat, Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas, as the party's vice presidential nominee. Roosevelt united the party around him, campaigning on the failures of the Hoover administration. He promised recovery with a "New Deal" for the American people.

Roosevelt won by a landslide in both the electoral and popular vote, carrying every state outside of the Northeast and receiving the highest percentage of the popular vote of any Democratic nominee up to that time. Hoover had won over 58% of the popular vote in the 1928 presidential election, but saw his share of the popular vote decline to 39.7%. Socialist Party nominee Norman Thomas won 2.2% of the popular vote. Subsequent Democratic landslides in the 1934 mid-term elections and the 1936 presidential election confirmed the commencement of the Fifth Party System, which would be dominated by Roosevelt's New Deal Coalition.[2]

Nominations

Democratic Party nomination

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | John Nance Garner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.jpg.webp) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 44th Governor of New York (1929–1932) |

39th Speaker of the House (1931–1933) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Democratic candidates:

- Franklin D. Roosevelt, governor of New York

- Al Smith (campaign), former governor of New York and 1928 Democratic presidential nominee

- John Nance Garner, U.S. Speaker of the House, of Texas

Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas

Speaker of the House John Nance Garner of Texas

The leading candidate for the Democratic nomination in 1932 was New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had won most of the primaries by wide margins.[3] However, the practice of state primaries was still uncommon in 1932, and most of the delegates at the convention were unbound by the results of a popular vote. Additionally, a two-thirds majority was required in order for any candidate to obtain the nomination. Speaker of the House John Nance Garner and former New York Governor Al Smith were the next two leading candidates behind Roosevelt, and while they did not have nearly as much support as he did, it was the hope of Roosevelt's opponents that he would be unable to obtain the two-thirds majority and that they could gain votes on later ballots or coalesce behind a dark horse candidate.[4]:3–4

The convention was held in Chicago between June 27 and July 2. The first vote was taken at 4:28 on the morning of July 2, after ten hours of speeches that had begun at 5:00 on the previous afternoon.[5] After three ballots, although Roosevelt had received far more delegates than any other candidate each time, he still did not have a two-thirds majority.[6] The delegates retired to get some rest, and over the next several hours, two major events occurred that shifted the results in Roosevelt's favor. First, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst, who had previously supported Garner, decided to support Roosevelt instead.[5] Then, Roosevelt's campaign managers, James Farley and Louis McHenry Howe, struck a deal with Garner: Garner would drop out of the race and support Roosevelt, and in return Roosevelt would name Garner as his running mate. With this agreement, Garner's supporters in California and Texas voted for Roosevelt on the fourth ballot, giving the governor a two-thirds majority and with it the presidential nomination.[4][6]

Republican Party nomination

| Herbert Hoover | Charles Curtis | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 31st President of the United States (1929–1933) |

31st Vice President of the United States (1929–1933) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Republican candidates:

- Herbert Hoover, President of the United States

- John J. Blaine, Senator from Wisconsin

- Joseph I. France, former Senator from Maryland

- James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr., former Senator from New York

Former Senator Joseph I. France from Maryland

Former Senator Joseph I. France from Maryland Former Senator James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr. from New York

Former Senator James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr. from New York

As the year 1932 began, the Republican Party believed Hoover's protectionism and aggressive fiscal policies would solve the depression. Whether they were successful or not, President Herbert Hoover controlled the party and had little trouble securing a re-nomination. Little-known former United States Senator Joseph I. France ran against Hoover in the primaries, but Hoover was often unopposed. France's primary wins were tempered by his defeat to Hoover in his home state of Maryland and the fact that few delegates to the national convention were chosen in the primaries.

Hoover's managers at the Republican National Convention, which met in Chicago between June 14 and 16, ran a tight ship, not allowing expressions of concern for the direction of the nation. He was nominated on the first ballot with 98% of the delegate vote.

The tally was spectacularly lopsided:

| Presidential Ballot, RNC 1932 | |

|---|---|

| Herbert Hoover | 1126.5 |

| John J. Blaine | 13 |

| Calvin Coolidge | 4.5 |

| Joseph I. France | 4 |

| James Wolcott Wadsworth, Jr. | 1 |

Both rural Republicans and hard-money Republicans (the latter hoping to nominate former President Calvin Coolidge) balked at the floor managers and voted against the renomination of Vice-President Charles Curtis, who won with just 55% of the delegate votes.

General election

Campaign

After making an airplane trip to the Democratic convention, Roosevelt accepted the nomination in person. In his speech, he stated, "ours must be a party of liberal thought, of planned action, of the enlightened international outlook, and of the greatest good to the greatest number of our citizens."[7] Roosevelt's trip to Chicago was the first of several successful, precedent-making moves designed to make him appear to be the candidate of change in the election.[8] Large crowds greeted Roosevelt as he traveled around the nation; his campaign song "Happy Days Are Here Again" became one of the most popular in American political history[4]:244 – and, indeed, the unofficial anthem of the Democratic Party.[9]

After their divisive convention, Democrats united around Roosevelt, who was able to draw more universal support than Al Smith had in 1928.[10] Roosevelt's Protestant background nullified the anti-Catholic attacks Smith faced in 1928, and The Depression seemed to be of much greater concern among the American public than previous cultural battles. Prohibition was a favorite Democratic target, with few Republicans trying to defend it given mounting demand to end prohibition and bring back beer, liquor, and the resulting tax revenues.[11]

In contrast, Hoover was not supported by many of the more prominent Republicans and violently opposed by others, in particular by a number of senators who had fought him throughout his administration and whose national reputation made their opposition of considerable importance. Many prominent Republicans even went so far as to espouse the cause of the Democratic candidate openly.[12]

Making matters worse for Hoover was the fact that many Americans blamed him for the Great Depression. The outrage caused by the deaths of veterans in the Bonus Army incident in the summer of 1932, combined with the catastrophic economic effects of Hoover's domestic policies, reduced his chances of a second term from slim to none. His attempts to campaign in public were a disaster, as he often had objects thrown at him or his vehicle as he rode through city streets.[13][14] Hoover's unpopularity resulted in Roosevelt adopting a cautious campaign strategy, focused on minimizing gaffes and keeping public attention directed towards his opponent.[15]

As Governor of New York, Roosevelt had garnered a reputation for promoting government help for the impoverished, providing a welcome contrast for many who saw Hoover as a do-nothing president.[16] Roosevelt emphasized working collectively through an expanded federal government to confront the economic crisis, a contrast to Hoover's emphasis on individualism.[15] During the campaign, Roosevelt ran on many of the programs that would later become part of the New Deal during his presidency.[17] It was said that "even a vaguely talented dog-catcher could have been elected president against the Republicans."[18] Hoover even received a letter from an Illinois man that advised, "Vote for Roosevelt and make it unanimous." [19]

Roosevelt employed the radio to great effect during the campaign. He was able to outline his platform while also improving the perception of his personality.[20] In March, 1932, The New York Times quoted radio producer John Carlile, who said that Roosevelt had a "tone of perfect sincerity," while for Hoover, "the microphone betrays deliberate effort in his radio voice."[21] The technology not only allowed Roosevelt to reach far more voters than he could via in-person campaigning, but also drew attention away from his paralysis due to polio.[20] Roosevelt took great pains to hide the effects of the disease from voters, instituting a "gentleman's agreement" with the press that he not be photographed in ways that would highlight his disability.[22]

The election was held on November 8, 1932.

Results

This was the first election since 1916 (16 years earlier) in which the Democratic candidate won.

Although the "other" vote (the combined vote total for candidates other than the nominees of the two major parties) of 1932 was three times that of 1928, it was considerably less than what had been recorded in 1920, the time of the greatest "other" vote, with the exception of the unusual conditions prevailing in 1912 and 1924.

Roosevelt, the Democratic candidate, received 22,817,883 votes (57.41%), the largest vote ever cast for a candidate for the Presidency up until that time, and over 1,425,000 more than that cast for Hoover four years earlier.

While Hoover had won a greater percentage of the vote in 1928 (as did Harding in 1920), the national swing of 17.59% to the Democrats impressed all who considered the distribution of the vote: more than one-sixth of the electorate had switched from supporting the Republicans to the Democrats. Only once before had there been a comparable shift, in 1920, when there was a 14.65% swing to the Republicans (while there had been a swing to the Democrats of 13.6% in 1912, this was from a three-candidate election).[12]

As of 2021, the swing for the Democrats from Smith in 1928 to Roosevelt remains the largest national swing of the electorate between presidential elections in the history of the United States. The largest swing since came for the Democrats in 1976, when the swing from George McGovern in 1972 to Jimmy Carter was 12.61%.

1932 was a political realignment election: not only did Roosevelt win a sweeping victory over Hoover, but Democrats significantly extended their control over the U.S. House, gaining 101 seats, and also gained 12 seats in the U.S. Senate to gain control of the chamber. Twelve years of Republican leadership came to an end, and 20 consecutive years of Democratic control of the White House began.[24]

Until 1932, the Republicans had controlled the Presidency for 52 of the previous 72 years, dating back to Abraham Lincoln being elected president in 1860. After 1932, Democrats would control the Presidency for 28 of the next 36 years.

Roosevelt led the poll in 2,722 counties, the greatest number ever carried by a candidate up until that time. Of these, 282 had never before been Democratic. Only 374 remained loyally Republican. However, that half of the total vote of the nation was cast in just eight states (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin) and that in these states, Hoover polled 8,592,163 votes. In one section (West South Central), the Republican percentage sank to 16.21%, but in no other section did the party poll less than 30% of the vote cast. However, the relative appeal of the two candidates in 1932 and the decline of the appeal of Hoover as compared with 1928 are shown in the fact that the Republican vote increased in 1932 in only 87 counties, while the Democratic vote increased in 3,003 counties.

The vote cast for Hoover, and the fact that in only one section of the nation (West South Central) did he have less than 500,000 votes and in only three states outside of the South less than 50,000 votes, made it clear that the nation remained a two-party electorate, and that everywhere, despite the overwhelming triumph of the Democrats, there was a party membership devoted to neither the new administration nor the proposals of the Socialist candidate who had polled 75% of the "other" vote (as well as the highest raw vote total of his campaigns).[25]

This election marks the last time as of 2021 that a Republican presidential candidate won a majority of black and African-American votes: as New Deal policies took effect, the strong support of black voters for these programs began a transition from their traditional support for Republicans to providing solid majorities for Democrats.

The Roosevelt ticket swept every region of the country except the Northeast, and carried many reliable Republican states that had not been carried by the Democrats since their electoral landslide of 1912, when the Republican vote was split in two.

Michigan voted Democratic for the first time since the emergence of the Republican Party in 1854, and Minnesota was carried by a Democrat for the first time since its admission to statehood in 1858, leaving Vermont as the only remaining state never to be carried by a Democratic candidate (which it would not be until 1964).

In contrast to the state's solid support of Republicans prior to this election, Minnesota has continued supporting Democrats in every presidential election but three since 1932 (the exceptions were in 1952, 1956, and 1972).

Roosevelt's victory with 472 electoral votes stood until the 1964 victory of Lyndon B. Johnson, who won 486 electoral votes in 1964, as the most ever won by a first-time contestant in a presidential election. Roosevelt also bettered the national record of 444 electoral votes set by Hoover only four years earlier, but would shatter his own record when he was re-elected in 1936 with 523 votes.

This was the last election in which Connecticut, Delaware, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania voted Republican until 1948.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Franklin Delano Roosevelt | Democratic | New York | 22,821,277 | 57.41% | 472 | John Nance Garner III | Texas | 472 |

| Herbert Clark Hoover (Incumbent) | Republican | California | 15,761,254 | 39.65% | 59 | Charles Curtis | Kansas | 59 |

| Norman Mattoon Thomas | Socialist | New York | 884,885 | 2.23% | 0 | James Hudson Maurer | Pennsylvania | 0 |

| William Edward Foster | Communist | Illinois | 103,307 | 0.26% | 0 | James W. Ford | Alabama | 0 |

| William David Upshaw | Prohibition | Georgia | 81,905 | 0.21% | 0 | Frank Stewart Regan | Illinois | 0 |

| William Hope Harvey | Liberty | Arkansas | 53,425 | 0.13% | 0 | Frank Hemenway | Washington | 0 |

| Verne L. Reynolds | Socialist Labor | New York | 34,038 | 0.09% | 0 | John William Aiken | Massachusetts | 0 |

| Jacob Sechler Coxey Sr. | Farmer-Labor | Ohio | 7,431 | 0.02% | 0 | Julius Reiter | Minnesota | 0 |

| Other | 4,376 | 0.01% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 39,751,898 | 100% | 531 | 531 | ||||

| Needed to win | 266 | 266 | ||||||

Source (popular vote): Leip, David. "1932 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 31, 2005.Source (electoral vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

Geography of results

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Cartographic gallery

Presidential election results by county

Presidential election results by county Democratic presidential election results by county

Democratic presidential election results by county Republican presidential election results by county

Republican presidential election results by county "Other" presidential election results by county

"Other" presidential election results by county Cartogram of presidential election results by county

Cartogram of presidential election results by county Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Democratic presidential election results by county Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county

Cartogram of Republican presidential election results by county Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Cartogram of "Other" presidential election results by county

Results by state

| States/districts won by Roosevelt/Garner |

| States/districts won by Hoover/Curtis |

| State | Roosevelt/Garner Democratic |

Hoover/Curtis Republican |

Thomas/Maurer Socialist |

Other | Margin | Total votes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | Votes | % | |||||||

| Alabama | 11 | 207,910 | 84.74 | 11 | 34,675 | 14.13 | – | 2,030 | 0.83 | – | 739 | 0.30 | – | 173,235 | 70.61 | 245,354 |

| Arizona | 3 | 79,264 | 67.03 | 3 | 36,104 | 30.53 | – | 2,618 | 2.21 | – | 265 | 0.22 | – | 43,160 | 36.50 | 118,251 |

| Arkansas | 9 | 189,602 | 85.96 | 9 | 28,467 | 12.91 | – | 1,269 | 0.58 | – | 1,224 | 0.55 | – | 161,135 | 73.06 | 220,562 |

| California | 22 | 1,324,157 | 58.39 | 22 | 847,902 | 37.39 | – | 63,299 | 2.79 | – | 32,608 | 1.44 | – | 476,255 | 21.00 | 2,267,966 |

| Colorado | 6 | 250,877 | 54.81 | 6 | 189,617 | 41.43 | – | 13,591 | 2.97 | – | 3,611 | 0.79 | – | 61,260 | 13.38 | 457,696 |

| Connecticut | 8 | 281,632 | 47.40 | – | 288,420 | 48.54 | 8 | 20,840 | 3.45 | – | 3,651 | 0.61 | – | −6,788 | −1.14 | 594,183 |

| Delaware | 3 | 54,319 | 48.11 | – | 57,073 | 50.55 | 3 | 1,376 | 1.22 | – | 133 | 0.12 | – | −2,754 | −2.44 | 112,901 |

| Florida | 7 | 206,307 | 74.68 | 7 | 69,170 | 25.04 | – | 775 | 0.28 | – | – | – | – | 137,137 | 49.64 | 276,252 |

| Georgia | 12 | 234,118 | 91.60 | 12 | 19,863 | 7.77 | – | 461 | 0.18 | – | 1,148 | 0.45 | – | 214,255 | 83.83 | 255,590 |

| Idaho | 4 | 109,479 | 58.66 | 4 | 71,417 | 38.27 | – | 526 | 0.28 | – | 5,203 | 2.79 | – | 38,062 | 20.39 | 186,625 |

| Illinois | 29 | 1,882,304 | 55.23 | 29 | 1,432,756 | 42.04 | – | 67,258 | 1.97 | – | 25,608 | 0.75 | – | 449,548 | 13.19 | 3,407,926 |

| Indiana | 14 | 862,054 | 54.67 | 14 | 677,184 | 42.94 | – | 21,388 | 1.36 | – | 16,301 | 1.03 | – | 184,870 | 11.72 | 1,576,927 |

| Iowa | 11 | 598,019 | 57.69 | 11 | 414,433 | 39.98 | – | 20,467 | 1.97 | – | 3,768 | 0.36 | – | 183,586 | 17.71 | 1,036,687 |

| Kansas | 9 | 424,204 | 53.56 | 9 | 349,498 | 44.13 | – | 18,276 | 2.31 | – | – | – | – | 74,706 | 9.43 | 791,978 |

| Kentucky | 11 | 580,574 | 59.06 | 11 | 394,716 | 40.15 | – | 3,853 | 0.39 | – | 3,920 | 0.40 | – | 185,858 | 18.91 | 983,063 |

| Louisiana | 10 | 249,418 | 92.79 | 10 | 18,853 | 7.01 | – | – | – | – | 533 | 0.20 | – | 230,565 | 85.77 | 268,804 |

| Maine | 5 | 128,907 | 43.19 | – | 166,631 | 55.83 | 5 | 2,489 | 0.83 | – | 417 | 0.14 | – | −37,724 | −12.64 | 298,444 |

| Maryland | 8 | 314,314 | 61.50 | 8 | 184,184 | 36.04 | – | 10,489 | 2.05 | – | 2,067 | 0.40 | – | 130,130 | 25.46 | 511,054 |

| Massachusetts | 17 | 800,148 | 50.64 | 17 | 736,959 | 46.64 | – | 34,305 | 2.17 | – | 8,702 | 0.55 | – | 63,189 | 4.00 | 1,580,114 |

| Michigan | 19 | 871,700 | 52.36 | 19 | 739,894 | 44.44 | – | 39,205 | 2.35 | – | 13,966 | 0.84 | – | 131,806 | 7.92 | 1,664,765 |

| Minnesota | 11 | 600,806 | 59.91 | 11 | 363,959 | 36.29 | – | 25,476 | 2.54 | – | 12,602 | 1.26 | – | 236,847 | 23.62 | 1,002,843 |

| Mississippi | 9 | 140,168 | 95.98 | 9 | 5,180 | 3.55 | – | 686 | 0.47 | – | – | – | – | 134,988 | 92.44 | 146,034 |

| Missouri | 15 | 1,025,406 | 63.69 | 15 | 564,713 | 35.08 | – | 16,374 | 1.02 | – | 3,401 | 0.21 | – | 460,693 | 28.62 | 1,609,894 |

| Montana | 4 | 127,286 | 58.80 | 4 | 78,078 | 36.07 | – | 7,891 | 3.65 | – | 3,224 | 1.49 | – | 49,208 | 22.73 | 216,479 |

| Nebraska | 7 | 359,082 | 62.98 | 7 | 201,177 | 35.29 | – | 9,876 | 1.73 | – | 2 | 0.00 | – | 157,905 | 27.70 | 570,137 |

| Nevada | 3 | 28,756 | 69.41 | 3 | 12,674 | 30.59 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 16,082 | 38.82 | 41,430 |

| New Hampshire | 4 | 100,680 | 48.99 | – | 103,629 | 50.42 | 4 | 947 | 0.46 | – | 264 | 0.13 | – | −2,949 | −1.43 | 205,520 |

| New Jersey | 16 | 806,394 | 49.49 | 16 | 775,406 | 47.59 | – | 42,988 | 2.64 | – | 4,719 | 0.29 | – | 30,988 | 1.90 | 1,629,507 |

| New Mexico | 3 | 95,089 | 62.72 | 3 | 54,217 | 35.76 | – | 1,776 | 1.17 | – | 524 | 0.35 | – | 40,872 | 26.96 | 151,606 |

| New York | 47 | 2,534,959 | 54.07 | 47 | 1,937,963 | 41.33 | – | 177,397 | 3.78 | – | 38,295 | 0.82 | – | 596,996 | 12.73 | 4,688,614 |

| North Carolina | 13 | 497,566 | 69.93 | 13 | 208,344 | 29.28 | – | 5,591 | 0.79 | – | – | – | – | 289,222 | 40.65 | 711,501 |

| North Dakota | 4 | 178,350 | 69.59 | 4 | 71,772 | 28.00 | – | 3,521 | 1.37 | – | 2,647 | 1.03 | – | 106,578 | 41.58 | 256,290 |

| Ohio | 26 | 1,301,695 | 49.88 | 26 | 1,227,319 | 47.03 | – | 64,094 | 2.46 | – | 16,620 | 0.64 | – | 74,376 | 2.85 | 2,609,728 |

| Oklahoma | 11 | 516,468 | 73.30 | 11 | 188,165 | 26.70 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 328,303 | 46.59 | 704,633 |

| Oregon | 5 | 213,871 | 57.99 | 5 | 136,019 | 36.88 | – | 15,450 | 4.19 | – | 3,468 | 0.94 | – | 77,852 | 21.11 | 368,808 |

| Pennsylvania | 36 | 1,295,948 | 45.33 | – | 1,453,540 | 50.84 | 36 | 91,223 | 3.19 | – | 18,466 | 0.65 | – | −157,592 | −5.51 | 2,859,177 |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 146,604 | 55.08 | 4 | 115,266 | 43.31 | – | 3,138 | 1.18 | – | 1,162 | 0.44 | – | 31,338 | 11.77 | 266,170 |

| South Carolina | 8 | 102,347 | 98.03 | 8 | 1,978 | 1.89 | – | 82 | 0.08 | – | – | – | – | 100,369 | 96.13 | 104,407 |

| South Dakota | 4 | 183,515 | 63.62 | 4 | 99,212 | 34.40 | – | 1,551 | 0.54 | – | 4,160 | 1.44 | – | 84,303 | 29.23 | 288,438 |

| Tennessee | 11 | 259,473 | 66.49 | 11 | 126,752 | 32.48 | – | 1,796 | 0.46 | – | 2,235 | 0.57 | – | 132,721 | 34.01 | 390,256 |

| Texas | 23 | 760,348 | 88.06 | 23 | 97,959 | 11.35 | – | 4,450 | 0.52 | – | 669 | 0.08 | – | 662,389 | 76.72 | 863,426 |

| Utah | 4 | 116,750 | 56.52 | 4 | 84,795 | 41.05 | – | 4,087 | 1.98 | – | 946 | 0.46 | – | 31,955 | 15.47 | 206,578 |

| Vermont | 3 | 56,266 | 41.08 | – | 78,984 | 57.66 | 3 | 1,533 | 1.12 | – | 197 | 0.14 | – | −22,718 | −16.58 | 136,980 |

| Virginia | 11 | 203,979 | 68.46 | 11 | 89,637 | 30.09 | – | 2,382 | 0.80 | – | 1,944 | 0.65 | – | 114,342 | 38.38 | 297,942 |

| Washington | 8 | 353,260 | 57.46 | 8 | 208,645 | 33.94 | – | 17,080 | 2.78 | – | 35,829 | 5.83 | – | 144,615 | 23.52 | 614,814 |

| West Virginia | 8 | 405,124 | 54.47 | 8 | 330,731 | 44.47 | – | 5,133 | 0.69 | – | 2,786 | 0.37 | – | 74,393 | 10.00 | 743,774 |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 707,410 | 63.46 | 12 | 347,741 | 31.19 | – | 53,379 | 4.79 | – | 6,278 | 0.56 | – | 359,669 | 32.26 | 1,114,808 |

| Wyoming | 3 | 54,370 | 56.07 | 3 | 39,583 | 40.82 | – | 2,829 | 2.92 | – | 180 | 0.19 | – | 14,787 | 15.25 | 96,962 |

| Total | 531 | 22,821,277 | 57.41 | 472 | 15,761,254 | 39.65 | 59 | 884,885 | 2.23 | – | 284,482 | 0.72 | 7,060,023 | 17.76 | 39,751,898 | |

| Roosevelt/Garner Democratic |

Hoover/Curtis Republican |

Thomas/Maurer Socialist |

Others | Margin | Total votes | |||||||||||

Close states

Margin of victory less than 5% (74 electoral votes):

- Connecticut, 1.14%

- New Hampshire, 1.43%

- New Jersey, 1.90%

- Delaware, 2.44%

- Ohio, 2.85%

- Massachusetts, 4.00%

Margin of victory between 5% and 10% (64 electoral votes):

- Pennsylvania, 5.51%

- Michigan, 7.92%

- Kansas, 9.43%

Tipping point state:

- Iowa, 17.71%

Statistics

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Democratic)

- Wilkinson County, Georgia 100.00%

- Armstrong County, South Dakota 100.00%

- Lancaster County, South Carolina 99.84%

- Sharkey County, Mississippi 99.82%

- Colleton County, South Carolina 99.69%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Republican)

- Johnson County, Tennessee 84.51%

- Jackson County, Kentucky 84.28%

- Leslie County, Kentucky 82.96%

- Owsley County, Kentucky 79.08%

- Sevier County, Tennessee 77.01%

Counties with Highest Percent of Vote (Other)

- Sheridan County, Montana 32.54%

- Thurston County, Washington 23.12%

- Clallam County, Washington 22.73%

- Berks County, Pennsylvania 22.17%

- Lake County, Minnesota 21.75%

See also

References

- "Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara.

- History of American Political Parties

- Kalb, Deborah, ed. (2015). Guide to U.S. Elections (7th ed.). CQ Press.

- Neal, Stephen (2010). Happy Days Are Here Again: The 1932 Democratic Convention, the Emergence of FDR--and How America Was Changed Forever. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780062015419.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 94.

- Henning, Arthur S. (July 2, 1932). "Pick Roosevelt; Here Today". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 13, 2020.(subscription required)

- "Address Accepting the Presidential Nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Alter, Jonathan (2006). The defining moment : FDR's hundred days and the triumph of hope. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-0-7432-4600-2.

- Arnold Shaw, The jazz age: popular music in the 1920s (1989) p. 228

- "The Election of 1932 – Franklin D. Roosevelt and the First New Deal". boundless.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- William E. Leuchtenburg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal 1932–1940 (1963) pp. 1–17

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, pg. 29

- "Overall Unemployment Rate in the U.S. Civilian Labor Force, 1920–2007 – Infoplease.com". Infoplease.com. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- "Timeline of the Great Depression". Hyperhistory.com. Retrieved November 4, 2008.

- William E. Leuchtenburg. "Franklin D. Roosevelt: Campaigns and Elections". Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Leuchtenberg, William E. (2009). Herbert Hoover. Times Books. pp. 138–139.

- Rauchway, Eric (2019). "The New Deal Was on the Ballot in 1932". Modern American History. 2 (2): 201–213. doi:10.1017/mah.2018.42. ISSN 2515-0456.

- Cambell, Jeff (November 19, 2008). "Hoover's Popularity". Lonely Planet.

- Will, George F. (November 9, 2000). "No, the System Worked". Washington Post. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- O'Mara, Margaret. Pivotal Tuesdays. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 97.

- "Search For Ideal Radio Voice Is An Unending Task". The New York Times. March 20, 1932. Retrieved October 13, 2020.(subscription required)

- Pressman, Matthew (July 12, 2013). "The myth of FDR's secret disability". Time. Retrieved August 12, 2013.

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932 – Google Books. Stanford University Press. 1934. ISBN 9780804716963. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- Gibbs, Nancy (November 10, 2008). "When New President Meets Old, It's Not Always Pretty". Time.

- The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932, Edgar E. Robinson, p. 30

- "1932 Presidential General Election Data – National". Retrieved April 8, 2013.

Further reading

- Andersen, Kristi. The Creation of a Democratic Majority: 1928–1936 (1979), statistical study of voting patterns

- Burns, James Macgregor. Roosevelt the Lion and the Fox (1956) online pp 123–52.

- Carcasson, Martin. "Herbert Hoover and the presidential campaign of 1932: The failure of apologia." Presidential Studies Quarterly 28.2 (1998): 349–365. in JSTOR

- Eden, Robert (1993). "On the Origins of the Regime of Pragmatic Liberalism: John Dewey, Adolf A. Berle, and FDR's Commonwealth Club Address of 1932". Studies in American Political Development. 7: 74–150. doi:10.1017/S0898588X00000699.

- Freidel, Frank Franklin D. Roosevelt The Triumph (1956) covers 1929–32 in depth online

- Freidel, Frank. "Election of 1932", in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., ed., The Coming to Power: Critical Presidential Elections in American History (1981)

- Gosnell, Harold F., Champion Campaigner: Franklin D. Roosevelt (1952)

- Gosnell, Harold F.; Gill, Norman N. (1935). "An Analysis of the 1932 Presidential Vote in Chicago". American Political Science Review. 29 (6): 967–984. doi:10.2307/1947313. JSTOR 1947313.

- Houck, Davis W. (2004). "FDR's Commonwealth Club Address: Redefining Individualism, Adjudicating Greatness". Rhetoric & Public Affairs. 7 (3): 259–282. doi:10.1353/rap.2005.0006.

- Hoover, Herbert. The Memoirs of Herbert Hoover: The Great Depression, 1929–1941 (1952)

- Nicolaides, Becky M. (1988). "Radio electioneering in the American presidential campaigns of 1932 and 1936". Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television. 8 (2): 115–138. doi:10.1080/01439688800260171.

- O'Mara, Margaret (2015). Pivotal Tuesdays. doi:10.9783/9780812291711. ISBN 9780812291711.

- Peel, Roy V.; Donnelly, Thomas C. (1936). "The 1932 Campaign: An Analysis". Journal of Educational Sociology. 9 (8): 510. doi:10.2307/2262331. JSTOR 2262331.

- Pietrusza, David 1932: The Rise of Hitler and FDR: Two Tales of Politics, Betrayal and Unlikely Destiny (2015)

- Ritchie, Donald A. Electing FDR: The New Deal Campaign of 1932 (2007)

- Ritchie, Donald A. (2011). "The Election of 1932". A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt. pp. 77–95. doi:10.1002/9781444395181.ch5. ISBN 9781444395181.

- Robinson, Edgar Eugene. The Presidential Vote, 1896–1932 (Stanford university press, 1940) voting returns for every county

- Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M. The Crisis of the Old Order (1957), pp 427–54 online

Primary sources

- Chester, Edward W A guide to political platforms (1977) online

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840-1964 (1965) online 1840-1956

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to United States presidential election, 1932. |

- United States presidential election of 1932 at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- 1932 popular vote by counties

- How close was the 1932 election? – Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Election of 1932 in Counting the Votes