United States presidential election

The election of the president and the vice president of the United States is an indirect election in which citizens of the United States who are registered to vote in one of the fifty U.S. states or in Washington, D.C., cast ballots not directly for those offices, but instead for members of the Electoral College.[note 1] These electors then cast direct votes, known as electoral votes, for president, and for vice president. The candidate who receives an absolute majority of electoral votes (at least 270 out of 538, since the Twenty-Third Amendment granted voting rights to citizens of D.C.) is then elected to that office. If no candidate receives an absolute majority of the votes for president, the House of Representatives elects the president; likewise if no one receives an absolute majority of the votes for vice president, then the Senate elects the vice president.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the United States |

|

|

The Electoral College and its procedure are established in the U.S. Constitution by Article II, Section 1, Clauses 2 and 4; and the Twelfth Amendment (which replaced Clause 3 after its ratification in 1804). Under Clause 2, each state casts as many electoral votes as the total number of its Senators and Representatives in Congress, while (per the Twenty-third Amendment, ratified in 1961) Washington, D.C., casts the same number of electoral votes as the least-represented state, which is three. Also under Clause 2, the manner for choosing electors is determined by each state legislature, not directly by the federal government. Many state legislatures previously selected their electors directly, but over time all switched to using the popular vote to choose electors. Once chosen, electors generally cast their electoral votes for the candidate who won the plurality in their state, but 18 states do not have provisions that specifically address this behavior; those who vote in opposition to the plurality are known as "faithless" or "unpledged" electors.[1] In modern times, faithless and unpledged electors have not affected the ultimate outcome of an election, so the results can generally be determined based on the state-by-state popular vote. In addition, most of the time, the winner of a US presidential election also wins the national popular vote. There were four exceptions since all states had the electoral system we know today. They happened in 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016 and were all losses of three percentage points or less.

Presidential elections occur quadrennially on leap years with registered voters casting their ballots on Election Day, which since 1845 has been the first Tuesday after November 1.[2][3][4] This date coincides with the general elections of various other federal, state, and local races; since local governments are responsible for managing elections, these races typically all appear on one ballot. The Electoral College electors then formally cast their electoral votes on the first Monday after December 12 at their state's capital. Congress then certifies the results in early January, and the presidential term begins on Inauguration Day, which since the passage of the Twentieth Amendment has been set at January 20.

The nomination process, consisting of the primary elections and caucuses and the nominating conventions, was not specified in the Constitution, but was developed over time by the states and political parties. These primary elections are generally held between January and June before the general election in November, while the nominating conventions are held in the summer. Though not codified by law, political parties also follow an indirect election process, where voters in the fifty states, Washington, D.C., and U.S. territories, cast ballots for a slate of delegates to a political party's nominating convention, who then elect their party's presidential nominee. Each party may then choose a vice presidential running mate to join the ticket, which is either determined by choice of the nominee or by a second round of voting. Because of changes to national campaign finance laws since the 1970s regarding the disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns, presidential candidates from the major political parties usually declare their intentions to run as early as the spring of the previous calendar year before the election (almost 21 months before Inauguration Day).[5]

History

Electoral College

Article Two of the Constitution originally established the method of presidential elections, including the creation of the Electoral College, the result of a compromise between those constitutional framers who wanted the Congress to choose the president, and those who preferred a national popular vote.[6]

As set forth in Article Two, each state is allocated a number of electors equal to the number of its delegates in both houses of Congress, combined. In 1961, the ratification of the Twenty-Third Amendment granted a number of electors to the District of Columbia, an amount equal to the number of electors allocated to the least populous state. However, U.S. territories are not allocated electors, and therefore are not represented in the Electoral College.

State legislatures

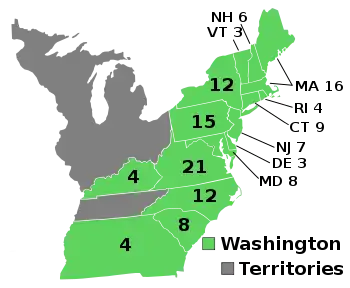

Constitutionally, the legislature of each state determines how its electors are chosen; Article II, Section 1, Clause 2 states that each state shall appoint electors "in such Manner as the Legislature Thereof May Direct".[7] During the first presidential election in 1789, only 6 of the 13 original states chose electors by any form of popular vote.[note 2]

Gradually throughout the years, the states began conducting popular elections to choose their slate of electors. In 1800, only five of the 16 states chose electors by a popular vote; by 1824, after the rise of Jacksonian democracy, the proportion of states that chose electors by popular vote had sharply risen to 18 out of 24 states.[8] This gradual movement toward greater democratization coincided with a gradual decrease in property restrictions for the franchise.[8] By 1840, only one of the 26 states (South Carolina) still selected electors by the state legislature.[9]

Vice presidents

Under the original system established by Article Two, electors cast votes for two different candidates for president. The candidate with the highest number of votes (provided it was a majority of the electoral votes) became the president, and the second-place candidate became the vice president. This presented a problem during the presidential election of 1800 when Aaron Burr received the same number of electoral votes as Thomas Jefferson and challenged Jefferson's election to the office. In the end, Jefferson was chosen as the president because of Alexander Hamilton's influence in the House.

In response to the 1800 election, the Twelfth Amendment was passed, requiring electors to cast two distinct votes: one for president and another for vice president. While this solved the problem at hand, it reduced the prestige of the vice presidency, as the office was no longer held by the leading challenger for the presidency. The separate ballots for president and vice president became something of a moot issue later in the 19th century when it became the norm for popular elections to determine a state's Electoral College delegation. Electors chosen this way are pledged to vote for a particular presidential and vice presidential candidate (offered by the same political party). Although the president and vice president are legally elected separately, in practice they are chosen together.

Tie votes

The Twelfth Amendment also established rules when no candidate wins a majority vote in the Electoral College. In the presidential election of 1824, Andrew Jackson received a plurality, but not a majority, of electoral votes cast. The election was thrown to the House, and John Quincy Adams was elected president. A deep rivalry resulted between Andrew Jackson and House Speaker Henry Clay, who had also been a candidate in the election.

Popular vote

Since 1824, aside from the occasional "faithless elector", the popular vote indirectly determines the winner of a presidential election by determining the electoral vote, as each state or district's popular vote determines its electoral college vote. Although the nationwide popular vote does not directly determine the winner of a presidential election, it does strongly correlate with who is the victor. In 54 of the 59 total elections held so far (about 91 percent), the winner of the national popular vote has also carried the Electoral College vote. The winners of the nationwide popular vote and the Electoral College vote have differed only in close elections. In highly competitive elections, candidates focus on turning out their vote in the contested swing states critical to winning an electoral college majority, so they do not try to maximize their popular vote by real or fraudulent vote increases in one-party areas.[10]

However, candidates have failed to get the most votes in the nationwide popular vote in a presidential election and still won. In the 1824 election, Jackson won the popular vote, but no one received a majority of electoral votes. According to the Twelfth Amendment, the House must choose the president out of the top three people in the election. Clay had come in fourth, so he threw his support to Adams, who then won. Because Adams later named Clay his Secretary of State, Jackson's supporters claimed that Adams gained the presidency by making a deal with Clay. Charges of a "corrupt bargain" followed Adams through his term.

In 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016, the winner of the electoral vote lost the popular vote outright. Numerous constitutional amendments have been submitted seeking to replace the Electoral College with a direct popular vote, but none has ever successfully passed both Houses of Congress. Another alternate proposal is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an interstate compact whereby individual participating states agree to allocate their electors based on the winner of the national popular vote instead of just their respective statewide results.

Election dates

The presidential election day was established on a Tuesday in November because of the factors involved (weather, harvests and worship) when voters used to travel to the polls by horse, Tuesday was an ideal day because it allowed people to worship on Sunday, ride to their county seat on Monday, and vote on Tuesday—all before market day, Wednesday. November also fits nicely between harvest time and harsh winter weather, which could be especially bad to people traveling by horse and buggy.[11]

Electoral Count Act of 1887

Congress passed the Electoral Count Act in 1887 in response to the disputed 1876 election, in which several states submitted competing slates of electors. The law established procedures for the counting of electoral votes. It has subsequently been codified into law in Title 3 of the United States Code. It also includes a "safe harbor" deadline where states must finally resolve any controversies over the selection of their electors.[12]

Inauguration day

Until 1937, presidents were not sworn in until March 4 because it took so long to count and report ballots, and because of the winner's logistical issues in moving to the capital. With improvements in transportation and the passage of the Twentieth Amendment, presidential inaugurations were moved forward to noon on January 20, thereby allowing presidents to start their duties sooner.[11]

Campaign spending

The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 was enacted to increase disclosure of contributions for federal campaigns. Subsequent amendments to law require that candidates to a federal office must file a Statement of Candidacy with the Federal Election Commission before they can receive contributions aggregating in excess of $5,000 or make expenditures aggregating in excess of $5,000. Thus, this began a trend of presidential candidates declaring their intentions to run as early as the Spring of the previous calendar year so they can start raising and spending the money needed for their nationwide campaign.[5]

Political parties

The first president, George Washington, was elected as an independent. Since the election of his successor, John Adams, in 1796, all winners of U.S. presidential elections have represented one of two major parties. Third parties have taken second place only twice, in 1860 and 1912. The last time a third (independent) candidate achieved significant success (although still finishing in third place) was Ross Perot in 1992, and the last time a third-party candidate received any electoral votes not from faithless electors was George Wallace in 1968.

Procedure

Eligibility requirements

Article Two of the Constitution stipulates that for a person to serve as president, the individual must be a natural-born citizen of the United States, at least 35 years old, and a resident of the United States for a period of no less than 14 years. A candidate may start running his or her campaign early before turning 35 years old or completing 14 years of residency, but must meet the age and residency requirements by Inauguration Day.[13] The Twenty-second Amendment to the Constitution also sets a term limit: a president cannot be elected to more than two terms.

The U.S. Constitution also has two provisions that apply to all federal officers appointed by the President, and debatably also to the presidency. When Senator Barack Obama was elected President a legal debate concluded that the President was not an “office under the United States”[14] for many reasons, but most significantly because Article I, Section 3, Clause 7 would violate the legal principle of surplussage[15] if the President were also a civil officer. There exists no case law to resolve the debate however public opinion seems to favor that the Presidency is also bound by the following qualifications:

Upon conviction at impeachment, the Senate may vote to disqualify that person from holding any “public office... under the United States” in the future. Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the election to any federal office of any person who engaged in insurrection after having held any federal or state office, rebellion or treason; this disqualification can be waived if such an individual gains the consent of two-thirds of both houses of Congress.

In addition, the Twelfth Amendment establishes that the vice-president must meet all the qualifications of being a president.

Although not a mandatory requirement, Federal campaign finance laws including the Federal Election Campaign Act state that a candidate who intends to receive contributions aggregating in excess of $5,000 or make expenditures aggregating in excess of $5,000, among others, must first file a Statement of Candidacy with the Federal Election Commission.[16] This has led presidential candidates, especially members from the two major political parties, to officially announce their intentions to run as early as the spring of the previous calendar year so they can start raising or spending the money needed for their nationwide campaign.[5] Potential candidates usually form exploratory committees even earlier to determine the feasibility of them actually running.

Decentralized election system and voter eligibility

The U.S. presidential election process, like all other elections in the United States, is a highly decentralized system.[17] While the U.S. Constitution does set parameters for the election of the president and other federal officials, state law, not federal, regulates most aspects of elections in the U.S., including the primaries, the eligibility of voters (beyond the basic constitutional definition), and the specific details of running each state's electoral college meeting. All elections, including federal, are administered by the individual states.[18]

Thus, the presidential election is really an amalgamation of separate state elections instead of a single national election run by the federal government. Candidates must submit separate filings in each of the 50 states if they want to qualify on each state's ballot, and the requirements for filing vary by state.[19]

The eligibility of an individual for voting is set out in the Constitution and regulated at state level. The 15th, 19th and 26th Amendments to the Constitution state that suffrage cannot be denied on grounds of race or color, sex, or age for citizens eighteen years or older, respectively. Beyond these basic qualifications, it is the responsibility of state legislatures to regulate voter eligibility and registration.[18] And the specific requirements for voter eligibility and registration also vary by state, e.g. some states ban convicted felons from voting.[20]

Nominating process

The modern nominating process of U.S. presidential elections consists of two major parts: a series of presidential primary elections and caucuses held in each state, and the presidential nominating conventions held by each political party. This process was never included in the Constitution, and thus evolved over time by the political parties to clear the field of candidates.

The primary elections are run by state and local governments, while the caucuses are organized directly by the political parties. Some states hold only primary elections, some hold only caucuses, and others use a combination of both. These primaries and caucuses are staggered generally between January and June before the federal election, with Iowa and New Hampshire traditionally holding the first presidential state caucus and primary, respectively.

Like the general election, presidential caucuses or primaries are indirect elections. The major political parties officially vote for their presidential candidate at their respective nominating conventions, usually all held in the summer before the federal election. Depending on each state's law and state's political party rules, when voters cast ballots for a candidate in a presidential caucus or primary, they may be voting to award delegates "bound" to vote for a candidate at the presidential nominating conventions, or they may simply be expressing an opinion that the state party is not bound to follow in selecting delegates to their respective national convention.

Unlike the general election, voters in the U.S. territories can also elect delegates to the national conventions. Furthermore, each political party can determine how many delegates to allocate to each state and territory. In 2012 for example, the Democratic and Republican party conventions each used two different formulas to allocate delegates. The Democrats-based theirs on two main factors: the proportion of votes each state gave to the Democratic candidate in the previous three presidential elections, and the number of electoral votes each state had in the Electoral College.[21] In contrast, the Republicans assigned to each state 10 delegates, plus three delegates per congressional district.[22] Both parties then gave a fixed number of delegates to each territory, and finally bonus delegates to states and territories that passed certain criteria.[21][22]

Along with delegates chosen during primaries and caucuses, state and U.S. territory delegations to both the Democratic and Republican party conventions also include "unpledged" delegates who have a vote. For Republicans, they consist of the three top party officials from each state and territory. Democrats have a more expansive group of unpledged delegates called "superdelegates", who are party leaders and elected officials.

Each party's presidential candidate also chooses a vice presidential nominee to run with him or her on the same ticket, and this choice is rubber-stamped by the convention.

If no single candidate has secured a majority of delegates (including both pledged and unpledged), then a "brokered convention" results. All pledged delegates are then "released" and can switch their allegiance to a different candidate. Thereafter, the nomination is decided through a process of alternating political horse trading, and additional rounds of re-votes.[23][24][25][26]

The conventions have historically been held inside convention centers, but since the late 20th century both the Democratic and Republican parties have favored sports arenas and domed stadiums to accommodate the increasing attendance.

Campaign strategy

One major component of getting elected to any office is running a successful campaign. There are, however, multiple ways to go about creating a successful campaign. Several strategies are employed by candidates from both sides of the political spectrum. Though the ideas may differ the goal of them all are the same, “…to mobilize supporters and persuade undecided voters…” (Sides et al., pg. 126 para, 2).[27]

The goal of any campaign strategy is to create an effective path to victory for the intended candidate. Joel Bradshaw is a political scientist who has four propositions necessary to develop such a strategy. The first one being, the separation of the eligible voters into three groups: Undecided voters, opponent voters, and your voting base. Second, is the utilization of previous election results and survey data that can be used to identify who falls into the categories given in section one. Third, it is not essential, nor possible to get the support of every voter in an election. The campaign focus should be held mostly to keeping the base and using data to determine how to swing the undecided voters. Fourth, now that the campaign has identified the ideal base strategy, it is now time to allocate resources properly to make sure your strategy is fulfilled to its extent, (Sides et al. pg. 126, para 4, and pg. 127, para 1).[27]

Campaign tactics are also an essential part of any strategy and rely mostly on the campaign's resources and the way they use them to advertise. Most candidates draw on a wide variety of tactics in the hopes to flood all forms of media, though they do not always have the finances. The most expensive form of advertising is running adds on broadcast television and is the best way to reach the largest number of potential voters. This tactic does have its drawback however as it is the most expensive form of advertisement. Even though it reaches the largest number of potential voters it is not the most effective way of swaying voters. The most effective way is believed to be through personal contact as many political scientists agree. It is confirmed that it is much more effective than contacting potential voters by email or by phone, (Sides et al., pg. 147 para, 2, 3).[27] These are just some of the wide variety of tactics used in campaigns.

The popular vote on Election Day

.jpg.webp)

Under the United States Constitution, the manner of choosing electors for the Electoral College is determined by each state's legislature. Although each state designates electors by popular vote, other methods are allowed. For instance, instead of having a popular vote, a number of states used to select presidential electors by a direct vote of the state legislature itself.

However, federal law does specify that all electors must be selected on the same day, which is "the Tuesday next after the first Monday in November,"[2] i.e., a Tuesday no earlier than November 2 and no later than November 8.[28] Today, the states and the District of Columbia each conduct their own popular elections on Election Day to help determine their respective slate of electors.

Generally, voters are required to vote on a ballot where they select the candidate of their choice. The presidential ballot is a vote "for the electors of a candidate" meaning the voter is not voting for the candidate, but endorsing a slate of electors pledged to vote for a specific presidential and vice presidential candidate.

Many voting ballots allow a voter to "blanket vote" for all candidates in a particular political party or to select individual candidates on a line by line voting system. Which candidates appear on the voting ticket is determined through a legal process known as ballot access. Usually, the size of the candidate's political party and the results of the major nomination conventions determine who is pre-listed on the presidential ballot. Thus, the presidential election ticket will not list every candidate running for president, but only those who have secured a major party nomination or whose size of their political party warrants having been formally listed. Laws allow other candidates pre-listed on a ticket, provided enough voters have endorsed that candidate, usually through a signature list.

The final way to be elected for president is to have one's name written in at the time of election as a write-in candidate. This method is used for candidates who did not fulfill the legal requirements to be pre-listed on the voting ticket. However, since a slate of electors must be associated with these candidates to vote for them (and someone for vice president) in the electoral college in the event they win the presidential election in a state, most states require a slate of electors be designated before the election in order for a write-in candidate to win, essentially meaning that most write-in votes do not count.[29] In any event, a write-in candidate has never won an election in a state for president of the United States. Write-in votes are also used by voters to express a distaste for the listed candidates, by writing in an alternative candidate for president such as Mickey Mouse or comedian Stephen Colbert (whose application was voted down by the South Carolina Democratic Party).

Because U.S. territories are not represented in the Electoral College, U.S. citizens in those areas do not vote in the general election for president. Guam has held straw polls for president since the 1980 election to draw attention to this fact.[30]

Electoral college

Most state laws establish a winner-take-all system, wherein the ticket that wins a plurality of votes wins all of that state's allocated electoral votes, and thus has their slate of electors chosen to vote in the Electoral College. Maine and Nebraska do not use this method, instead of giving two electoral votes to the statewide winner and one electoral vote to the winner of each Congressional district.

Each state's winning slate of electors then meets at their respective state's capital on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December to cast their electoral votes on separate ballots for president and vice president. Although Electoral College members can vote for anyone under the U.S. Constitution, 32 states plus the District of Columbia have laws against faithless electors,[31][32] those electors who do not cast their electoral votes for the person for whom they have pledged to vote. The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in the case Chiafalo v. Washington on July 6, 2020, that the constitution does not prevent states from penalizing or replacing faithless electors.

In early January, the total Electoral College vote count is opened by the sitting vice president, acting in his capacity as President of the Senate, and read aloud to a joint session of the incoming Congress, which was elected at the same time as the President. Members of Congress are free to object to any or all of a state's electoral vote count, provided that the objection is presented in writing and is signed by at least one member of each house of Congress. If such an objection is submitted, both houses of Congress adjourn to their respective chambers to debate and vote on the objection. The approval of both houses of Congress are required to invalidate those electoral votes in question.[33]

If no candidate receives a majority of the electoral vote (at least 270), the President is determined by the rules outlined by the Twelfth Amendment. Specifically, the selection of President would then be decided by a contingent election in a ballot of the House of Representatives. For the purposes of electing the President, each state has only one vote. A ballot of the Senate is held to choose the Vice President. In this ballot, each senator has one vote. The House has chosen the victor of the presidential race only twice, in 1800 and 1824; the Senate has chosen the victor of the vice-presidential race only once, in 1836.

If the president is not chosen by Inauguration Day, the vice president-elect acts as president. If neither are chosen by then, Congress by law determines who shall act as President, pursuant to the Twentieth Amendment.

Unless there are faithless electors, disputes, or other controversies, the events in December and January mentioned above are largely a formality since the winner can be determined based on the state-by-state popular vote results. Between the general election and Inauguration Day, this apparent winner is referred to as the "President-elect" (unless it is a sitting president who has won re-election).

Election calendar

The typical periods of the presidential election process are as follows, with the dates corresponding to the 2020 general election:

- Late 2018 to early 2019 – Candidates announce their intentions to run, and (if necessary) file their Statement of Candidacy with the Federal Election Commission

- June 2019 to April 2020 – Primary and caucus debates

- February 3 to June 16, 2020 – Primaries and caucuses

- Late May to August 2020 – Nominating conventions (including those of the minor third parties)

- September and October 2020 – Presidential election debates

- Tuesday November 3, 2020 – Election Day

- Monday December 14, 2020 – Electors cast their electoral votes

- Wednesday January 6, 2021 – Congress counts and certifies the electoral votes

Trends

Previous experience

Among the 45 persons who have served as president, only Donald Trump had never held a position in either government or the military prior to taking office.[34] The only previous experience Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, and Dwight D. Eisenhower had was in the military. Herbert Hoover previously served as the Secretary of Commerce. Everyone else served in elected public office before becoming president, such as being Vice President, a member of Congress, or a state or territorial governor.

Fifteen presidents also served as vice president. However, only John Adams (1796), Thomas Jefferson (1800), Martin Van Buren (1836), Richard Nixon (1968), George H. W. Bush (1988), and Joe Biden (2020) began their first term after winning an election. The remaining nine began their first term as president according to the presidential line of succession after the intra-term death or resignation of their predecessor. Of these, Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Harry S. Truman, and Lyndon B. Johnson were subsequently elected to a full term of their own, while John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, Andrew Johnson, Chester A. Arthur, and Gerald Ford were not. Ford's accession to the presidency is unique in American history in that he became vice president through the process prescribed by the Twenty-fifth Amendment rather than by winning an election, thus making him the only U.S. president to not have been elected to either office.

Sixteen presidents had previously served in the U.S. Senate, including four of the five who served between 1945 and 1974. However, only three were incumbent senators at the time they were elected president (Warren G. Harding in 1920, John F. Kennedy in 1960, and Barack Obama in 2008). Eighteen presidents had earlier served in the House of Representatives. However, only one was a sitting representative when elected to the presidency (James A. Garfield in 1880).

Four of the last seven presidents (Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush) have been governors of a state. Geographically, these presidents were from either very large states (Reagan from California, Bush from Texas) or from a state south of the Mason–Dixon line and east of Texas (Carter from Georgia, Clinton from Arkansas). In all, sixteen presidents have been former governors, including seven who were incumbent governors at the time of their election to the presidency.

The most common job experience, occupation or profession of U.S. presidents has been lawyer;[35] 26 presidents had served as attorneys. Twenty-two presidents were also in the military. Eight presidents had served as Cabinet Secretaries, with five of the six Presidents who served between 1801 and 1841 having held the office of U.S. Secretary of State.

After leaving office, one president, William Howard Taft, served as Chief Justice of the United States. Two others later served in Congress – John Quincy Adams in the House and Andrew Johnson in the Senate.

Technology and media

Advances in technology and media have also affected presidential campaigns. The invention of radio and then television gave way to reliance upon national political advertisements such as Lyndon B. Johnson's 1964 "Daisy", Ronald Reagan's 1984 "Morning in America", and George H. W. Bush's 1988 "Revolving Door", all of which became major factors. In 1992, George H. W. Bush's promise of "Read my lips: no new taxes" was extensively used in the commercials of Bill Clinton and Bush's other opponents with significant effect during the campaign.

Since the development of the internet in the mid-90s, Internet activism has also become an invaluable component of presidential campaigns, especially since 2000. The internet was first used in the 1996 presidential elections, but primarily as a brochure for the candidate online.[36] It was only used by a few candidates and there is no evidence of any major effect on the outcomes of that election cycle.[36]

In 2000, both candidates (George W. Bush and Al Gore) created, maintained, and updated campaign websites. But it was not until the 2004 presidential election cycle was the potential value of the internet seen. By the summer of 2003, ten people competing in the 2004 presidential election had developed campaign websites.[37] Howard Dean's campaign website from that year was considered a model for all future campaign websites. His website played a significant role in his overall campaign strategy.[37] It allowed his supporters to read about his campaign platform and provide feedback, donate, get involved with the campaign, and connect with other supporters.[36] A Gallup poll from January 2004 revealed that 49 percent of Americans have used the internet to get information about candidates, and 28 percent said they use the internet to get this information frequently.[36]

Use of the Internet for grassroots fundraising by US presidential candidates such as Howard Dean, Barack Obama, Ron Paul and Bernie Sanders established it as an effective political tool. In 2016, the use of social media was a key part of Donald Trump campaign. Trump and his opinions were established as constantly "trending" by posting multiple times per day, and his strong online influence was constantly reinforced.[38] Internet channels such as YouTube were used by candidates to share speeches and ads and to attack candidates by uploading videos of gaffes.[36]

A study done by the Pew Internet & American Life Project in conjunction with Princeton Survey Research Associates in November 2010 shows that 54% of adults in the United States used the internet to get information about the 2010 midterm elections and about specific candidates. This represents 73% of adult internet users. The study also showed that 22 percent of adult internet users used social networking sites or [[Twitter] to get information about and discuss the elections and 26 percent of all adults used cell phones to learn about or participate in campaigns.[39]

E-campaigning, as it has come to be called, is subject to very little regulation. On March 26, 2006, the Federal Election Commission voted unanimously to "not regulate political communication on the Internet, including emails, blogs and the creating of Web sites".[40] This decision made only paid political ads placed on websites subject to campaign finance limitations.[41] A comment was made about this decision by Roger Alan Stone of Advocacy Inc. which explains this loophole in the context of a political campaign: "A wealthy individual could purchase all of the e-mail addresses for registered voters in a congressional district ... produce an Internet video ad, and e-mail it along with a link to the campaign contribution page ... Not only would this activity not count against any contribution limits or independent expenditure requirements; it would never even need to be reported."[40]

A key part of the United States presidential campaigns is the use of media and framing. Candidates are able to frame their opponents and current issues in ways to affect the way voters will see events and the other presidential candidates.[42] This is known as "priming". For example, during the 2016 presidential election with candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, Trump successfully influenced the way voters thought about Clinton, while Clinton was less successful in doing so in return. Trump primed voters to think of Clinton as "Crooked Hillary" or a "Nasty Woman".[43] Trump played to the interests of his voters, and, while Clinton did so as well, her concentration of advertisements about defeating Trump was not always beneficial to her campaign. The media, and Trump, tended to focus on what was presented as her email scandal, and when voters thought about her that is what came to mind. Trump played into voters' anti-government interests, while Clinton appealed to the future of the country for the better of future children.[44] Trump was unexpectedly successful at connecting to what a huge portion of Americans perceived as their interests. It was not always Clinton's strong point, but that may not have been her fault. Americans vote based on whether they feel the country is in a time of gain or a time of loss.[42] Trump's campaigning and well-known slogan, "Make America Great Again", made Americans feel like the country was in a time of loss. When that happens, the electorate will be willing to take a risk on voting for a candidate without political experience as long as he or she is convincing enough.[42] Trump was convincing with his anti-everything rhetoric, and his message reached the electorate with the help of the media. Over half of the media coverage on Trump was focused on where he stood in the race, while only 12% focused on issues, stances, and political beliefs (including problematic comments).[43]

Criticism

|

January 2012 (4)

February 2012 (7)

March 2012 (23)

|

April 2012 (9)

May 2012 (7)

June 2012 (6)

|

The presidential election process is controversial, with critics arguing that it is inherently undemocratic, and discourages voter participation and turnout in many areas of the country. Because of the staggered nature of the primary season, voters in Iowa, New Hampshire and other small states which traditionally hold their primaries and caucuses first in January usually have a major impact on the races. Campaign activity, media attention, and voter participation are usually higher in these states, as the candidates attempt to build momentum and generate a bandwagon effect in these early primaries. Conversely, voters in California and other large states which traditionally hold their primaries last in June usually end up having no say in who the presidential candidates will be. The races are usually over by then, and thus the campaigns, the media, and voters have little incentive to participate in these late primaries. As a result, more states vie for earlier primaries to claim a greater influence in the process. However, compressing the primary calendar in this way limits the ability of lesser-known candidates to effectively corral resources and raise their visibility among voters, especially when competing with better-known candidates who have more financial resources and the institutional backing of their party's establishment. Primary and caucus reform proposals include a National Primary held on a single day; or the Interregional Primary Plan, where states would be grouped into six regions, and each region would rotate every election on who would hold their primaries first.

With the primary races usually over before June, the political conventions have mostly become scripted, ceremonial affairs. As the drama has left the conventions, and complaints grown that they were scripted and dull pep rallies, public interest and viewership has fallen off. After having offered gavel-to-gavel coverage of the major party conventions in the mid-20th century, the Big Three television networks now devote only approximately three hours of coverage (one hour per night).

Critics also argue that the Electoral College is archaic and inherently undemocratic. With all states, except Maine and Nebraska, using a winner-take-all system, both the Democratic and the Republican candidates are almost certain to win all the electoral votes from those states whose residents predominantly vote for the Democratic Party or the Republican Party, respectively. This encourages presidential candidates to focus exponentially more time, money, and energy campaigning in a few so-called "swing states", states in which no single candidate or party has overwhelming support. Such swing states like Ohio are inundated with campaign visits, saturation television advertising, get-out-the-vote efforts by party organizers, and debates. Meanwhile, candidates and political parties have no incentive to mount nationwide campaign efforts, or work to increase voter turnout, in predominantly Democratic Party "safe states" like California or predominantly Republican Party "safe states". In practice, the winner-take-all system also both reinforces the country's two-party system and decreases the importance of third and minor political parties.[45] Furthermore, a candidate can win the electoral vote without securing the greatest amount of the national popular vote, such as during the 1824, 1876, 1888, 2000 and 2016 elections. It is also possible to secure the necessary 270 electoral votes from only the eleven most populous states and then ignore the rest of the country.

Proposed changes to the election process

In 1844, Representative Samuel F. Vinton of Ohio proposed an amendment to the constitution that would replace the electoral college system with a lot system. The Joint Resolution called for each state to elect, by a simple majority, a presidential candidate of said state. Each state would notify Congress of the presidential election results. Congress would then inscribe the name of every state on uniform balls, equal to the number of said state's members of Congress, and deposit into a box. In a joint session of Congress, a ball would be drawn, and the elected candidate of the state of which is written on the drawn ball would be named president. A second ball would immediately be drawn after, and that state's candidate would be named vice-president. The resolution did not pass the House. Representative Vinton proposed an identical amendment in 1846. Again, it was unsuccessful. The driving force behind the introduction of the resolution is unclear, as there is no recorded debate for either proposal.[46]

Other constitutional amendments, such as the Every Vote Counts Amendment, have been proposed seeking to replace the Electoral College with a direct popular vote, which proponents argue would increase turnout and participation. Other proposed reforms include the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an interstate compact without Congressional authorization, whereby individual participating states agree to allocate their electors based on the winner of the national popular vote, instead of voting their respective statewide results. Another proposal is for every state to simply adopt the District system used by Maine and Nebraska: give two electoral votes to the statewide winner and one electoral vote to the winner of each Congressional district. The Automatic Plan would replace the Electors with an automatic tallying of votes to eliminate the faithless elector affecting the outcome of the election. The Proportional Plan, often compared to the District Plan, would distribute electoral votes in each state in proportion to the popular vote, introducing third party effects in election outcomes. The House Plan would require a constitutional amendment to allocate electors based on the House apportionment alone to lessen small state advantage. Direct election plans and bonus plans both place a higher valuation on the popular vote for president.[47]

Electoral college results

This is a table of electoral college results. Included are candidates who received at least one electoral vote or at least five percent of the popular vote.

Popular vote results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | George Washington | 43,782 | 100% | |

| Federalist | John Adams (vice)[note 44] | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | John Jay | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Robert H. Harrison | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | John Rutledge | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | John Hancock | n/a | n/a | |

| Anti-Administration | George Clinton | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Samuel Huntington | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | John Milton | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | James Armstrong | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Benjamin Lincoln | n/a | n/a | |

| Anti-Administration | Edward Telfair | n/a | n/a | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent | George Washington | 28,579 | 100% | |

| Federalist | John Adams (vice) | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | George Clinton | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | Thomas Jefferson | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | Aaron Burr | n/a | n/a | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federalist | John Adams | 35,726 | 53.4% | |

| Democratic–Republican | Thomas Jefferson (vice) | 31,115 | 46.5% | |

| Democratic–Republican | Aaron Burr | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | Samuel Adams | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Oliver Ellsworth | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | George Clinton | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | John Jay | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | James Iredell | n/a | n/a | |

| Independent | George Washington | n/a | n/a | |

| Democratic–Republican | John Henry | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Samuel Johnston | n/a | n/a | |

| Federalist | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | n/a | n/a | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | Thomas Jefferson/Aaron Burr | 41,330 | 61.4% | |

| Federalist | John Adams/Charles Cotesworth Pinckney | 25,952 | 38.6% | |

| Federalist | John Adams/John Jay | 0 | 0% | |

| House Vote for President, 1801 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| CT | DE | GA | KY | MD | MA | NH | NJ | NY | NC | PN | RI | SC | TN | VT | VI | ||||||||

| 0-7 | 0-0-1 | 1-0 | 2-0 | 4-0-4 | 3-11 | 0-4 | 3-2 | 6-4 | 6-4 | 9-4 | 0-2 | 0-0-4 | 1-0 | 1-0-1 | 14-5 | ||||||||

| State delegations won by Jefferson are color coded in green, and those won by Burr in red. Vote results listed in that order, with abstentions at end. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | Thomas Jefferson/George Clinton | 104,110 | 72.8% | |

| Federalist | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney/Rufus King | 38,919 | 27.2% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

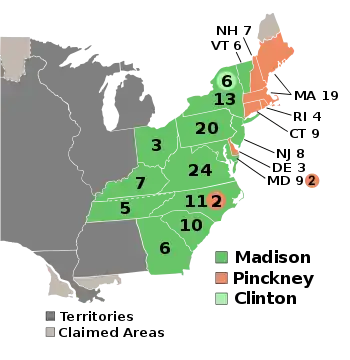

| Democratic–Republican | James Madison/George Clinton | 124,732 | 64.7% | |

| Federalist | Charles Cotesworth Pinckney/Rufus King | 62,431 | 32.4% | |

| Democratic–Republican | George Clinton/James Madison and James Monroe | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | James Madison/Elbridge Gerry | 140,431 | 50.4% | |

| Democratic–Republican | DeWitt Clinton[note 45]/Jared Ingersoll and Elbridge Gerry | 132,781 | 47.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | James Monroe/Daniel D. Tompkins | 76,592 | 68.2% | |

| Federalist | Rufus King/Multiple | 34,740 | 30.9% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | James Monroe/Daniel D. Tompkins | 87,343 | 80.6% | |

| Democratic–Republican | John Quincy Adams/Richard Rush (Federalist) | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic–Republican | John Quincy Adams/John C. Calhoun and Andrew Jackson | 113,122 | 30.9%[note 46] | |

| Democratic–Republican | Andrew Jackson/John C. Calhoun | 151,271 | 41.4% | |

| Democratic–Republican | William H. Crawford/Multiple | 40,856 | 11.2% | |

| Democratic–Republican | Henry Clay/Multiple | 47,531 | 13% | |

This election was in many ways unique in American history: several different factions of the Democratic-Republican Party were named after the last names of the candidates in this race, and nominated their own candidates. As no candidate received a majority of electoral votes, the House of Representatives chose Adams to be president.

| House Vote for President, 1824 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| AL | CT | DE | GA | IL | IN | KY | LA | ME | MD | MA | MS | MO | NH | NJ | NY | NC | OH | PN | RI | SC | TN | VT | VI |

| 0-3-0 | 6-0-0 | 0-0-1 | 0-0-7 | 1-0-0 | 0-3-0 | 8-4-0 | 2-1-0 | 7-0-0 | 5-3-1 | 12-1-0 | 0-1-0 | 1-0-0 | 6-0-0 | 1-5-0 | 18-2-14 | 1-1-10 | 10-2-2 | 1-25-0 | 2-0-0 | 0-9-0 | 0-9-0 | 5-0-0 | 1-1-19 |

| State delegations that Adams won are colored in green, blue for Jackson, and orange for Crawford. Vote results listed in that order. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andrew Jackson/John C. Calhoun | 642,553 | 56.0% | |

| National Republican | John Quincy Adams/Richard Rush | 500,897 | 43.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Andrew Jackson/Martin Van Buren | 701,780 | 54.2% | |

| National Republican | Henry Clay/John Sergeant | 484,205 | 37.4% | |

| Nullifier | John Floyd/Henry Lee | 0 | 0% | |

| Anti-Masonic | William Wirt/Amos Ellmaker | 100,715 | 7.8% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Martin Van Buren/Richard Mentor Johnson | 764,176 | 56.0% | |

| Whig | William Henry Harrison/Francis Granger | 549,907 | 36.6% | |

| Whig | Hugh L. White/John Tyler | 146,107 | 9.7% | |

| Whig | Daniel Webster/Francis Granger | 41,201 | 2.7% | |

| Whig | Willie Person Mangum/John Tyler | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whig | William Henry Harrison/John Tyler | 1,275,390 | 52.9% | |

| Democratic | Martin Van Buren/Richard Mentor Johnson | 1,128,854 | 46.8% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James K. Polk/George M. Dallas | 1,339,494 | 49.5% | |

| Whig | Henry Clay/Theodore Frelinghuysen | 1,300,004 | 48.1% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whig | Zachary Taylor/Millard Fillmore | 1,361,393 | 47.3% | |

| Democratic | Lewis Cass/William Orlando Butler | 1,223,460 | 42.5% | |

| Free Soil | Martin Van Buren/Charles Francis Adams Sr. | 291,501 | 10.1% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Franklin Pierce/William R. King | 1,607,510 | 50.8% | |

| Whig | Winfield Scott/William Alexander Graham | 1,386,942 | 43.9% | |

| Free Soil | John P. Hale/George Washington Julian | 155,210 | 4.9% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James Buchanan/John C. Breckinridge | 1,836,072 | 45.3% | |

| Republican | John C. Frémont/William L. Dayton | 1,342,345 | 33.1% | |

| Know Nothing | Millard Fillmore/Andrew Jackson Donelson | 873,053 | 21.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Abraham Lincoln/Hannibal Hamlin | 1,865,908 | 39.8% | |

| Southern Democratic | John C. Breckinridge/Joseph Lane | 848,019 | 18.1% | |

| Constitutional Union | John Bell/Edward Everett | 590,901 | 12.6% | |

| Democratic | Stephen A. Douglas/Herschel V. Johnson | 1,380,202 | 29.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Abraham Lincoln/Andrew Johnson | 2,218,388 | 55.0% | |

| Democratic | George B. McClellan/George H. Pendleton | 1,812,807 | 45.0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ulysses S. Grant/Schuyler Colfax | 3,013,650 | 52.7% | |

| Democratic | Horatio Seymour/Francis Preston Blair Jr. | 2,708,744 | 47.3% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ulysses S. Grant/Henry Wilson | 3,598,235 | 55.6% | |

| Liberal Republican | Horace Greeley/Benjamin Gratz Brown | 2,834,761 | 43.8% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rutherford B. Hayes/William A. Wheeler | 4,034,142 | 47.9%[note 46] | |

| Democratic | Samuel J. Tilden/Thomas A. Hendricks | 4,286,808 | 50.9% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | James A. Garfield/Chester A. Arthur | 4,446,158 | 48.3% | |

| Democratic | Winfield Scott Hancock/William Hayden English | 4,444,260 | 48.3% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Grover Cleveland/Thomas A. Hendricks | 4,914,482 | 48.9% | |

| Republican | James G. Blaine/John A. Logan | 4,856,903 | 48.3% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Benjamin Harrison/Levi P. Morton | 5,443,892 | 47.8%[note 46] | |

| Democratic | Grover Cleveland/Allen G. Thurman | 5,534,488 | 48.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Grover Cleveland/Adlai Stevenson I | 5,553,898 | 46% | |

| Republican | Benjamin Harrison/Whitelaw Reid | 5,190,819 | 43% | |

| Populist | James B. Weaver/James G. Field | 1,026,595 | 8.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William McKinley/Garret Hobart | 7,111,607 | 51% | |

| Democratic | William Jennings Bryan/Arthur Sewall | 6,509,052 | 46.7% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William McKinley/Theodore Roosevelt | 7,228,864 | 51.6% | |

| Democratic | William Jennings Bryan/Adlai Stevenson I | 6,370,932 | 45.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Theodore Roosevelt/Charles W. Fairbanks | 7,630,457 | 56.4% | |

| Democratic | Alton B. Parker/Henry G. Davis | 5,083,880 | 37.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | William Howard Taft/James S. Sherman | 7,678,335 | 51.6% | |

| Democratic | William Jennings Bryan/John W. Kern | 6,408,979 | 43% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Woodrow Wilson/Thomas R. Marshall | 6,296,284 | 41.8% | |

| Progressive | Theodore Roosevelt/Hiram Johnson | 4,122,721 | 27% | |

| Republican | William Howard Taft/Nicholas Murray Butler | 3,486,242 | 23.2% | |

| Socialist | Eugene V. Debs/Emil Seidel | 901,551 | 6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

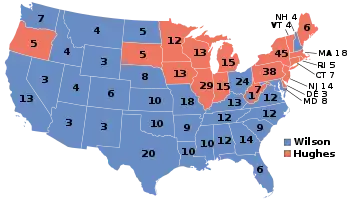

| Democratic | Woodrow Wilson/Thomas R. Marshall | 9,126,868 | 49.2% | |

| Republican | Charles Evans Hughes/Charles W. Fairbanks | 8,548,728 | 46.1% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Warren G. Harding/Calvin Coolidge | 16,114,093 | 60.3% | |

| Democratic | James M. Cox/Franklin D. Roosevelt | 9,139,661 | 34.2% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Calvin Coolidge/Charles G. Dawes | 15,723,789 | 54% | |

| Democratic | John W. Davis/Charles W. Bryan | 8,386,242 | 28.8% | |

| Progressive | Robert La Follette/Burton K. Wheeler | 4,831,706 | 16.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Herbert Hoover/Charles Curtis | 21,427,123 | 58.2% | |

| Democratic | Al Smith/Joseph Taylor Robinson | 15,015,464 | 40.8% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

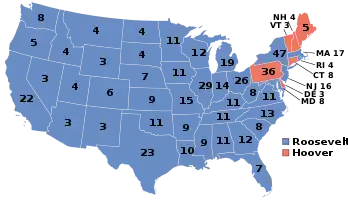

| Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt/John Nance Garner | 22,821,277 | 57.4% | |

| Republican | Herbert Hoover/Charles Curtis | 15,761,254 | 39.7% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt/John Nance Garner | 27,752,648 | 60.8% | |

| Republican | Alf Landon/Frank Knox | 16,681,862 | 36.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt/Henry A. Wallace | 27,313,945 | 54.7% | |

| Republican | Wendell Willkie/Charles L. McNary | 22,347,744 | 44.8% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Franklin D. Roosevelt/Harry S. Truman | 25,612,916 | 53.4% | |

| Republican | Thomas E. Dewey/John W. Bricker | 22,017,929 | 45.9% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harry S. Truman/Alben W. Barkley | 24,179,347 | 49.6% | |

| Republican | Thomas E. Dewey/Earl Warren | 21,991,292 | 45.1% | |

| Dixiecrat | Strom Thurmond/Fielding L. Wright | 1,175,930 | 2.4% | |

| Progressive | Henry A. Wallace/Glen H. Taylor | 1,157,328 | 2.4% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Dwight D. Eisenhower/Richard Nixon | 34,075,529 | 55.2% | |

| Democratic | Adlai Stevenson II/John Sparkman | 27,375,090 | 44.3% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Dwight D. Eisenhower/Richard Nixon | 35,579,180 | 57.4% | |

| Democratic | Adlai Stevenson II/Estes Kefauver | 26,028,028 | 42% | |

| Dixiecrat | T. Coleman Andrews/Thomas Werdel | 305,274 | 0.5% | |

| Democratic | Walter Burgwyn Jones/Herman Talmadge | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | John F. Kennedy/Lyndon B. Johnson | 34,220,984 | 49.7% | |

| Republican | Richard Nixon/Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. | 34,108,157 | 49.6% | |

| Dixiecrat | Harry F. Byrd/Strom Thurmond | 610,409 | 0.4% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Lyndon B. Johnson/Hubert Humphrey | 43,127,041 | 61% | |

| Republican | Barry Goldwater/William E. Miller | 27,175,754 | 38.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Richard Nixon/Spiro Agnew | 31,783,783 | 43.4% | |

| Democratic | Hubert Humphrey/Edmund Muskie | 31,271,839 | 42.7% | |

| American Independent | George Wallace/Curtis LeMay | 9,901,118 | 13.5% | |

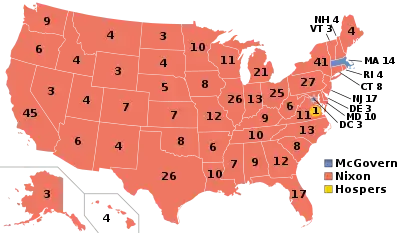

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Richard Nixon/Spiro Agnew | 47,168,710 | 60.7% | |

| Democratic | George McGovern/Sargent Shriver | 29,173,222 | 37.5% | |

| Libertarian | John Hospers/Tonie Nathan | 3,674 | <0.01% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jimmy Carter/Walter Mondale | 40,831,881 | 50.1% | |

| Republican | Gerald Ford/Bob Dole | 39,148,634 | 48% | |

| Republican | Ronald Reagan/Bob Dole | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ronald Reagan/George H. W. Bush | 43,903,230 | 50.7% | |

| Democratic | Jimmy Carter/Walter Mondale | 35,480,115 | 41% | |

| Independent | John B. Anderson/Patrick Lucey | 5,719,850 | 6.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ronald Reagan/George H. W. Bush | 54,455,472 | 58.8% | |

| Democratic | Walter Mondale/Geraldine Ferraro | 37,577,352 | 40.6% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | George H. W. Bush/Dan Quayle | 48,886,597 | 53.4% | |

| Democratic | Michael Dukakis/Lloyd Bentsen | 41,809,476 | 45.6% | |

| Democratic | Lloyd Bentsen/Michael Dukakis | 0 | 0% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Clinton/Al Gore | 44,909,806 | 43% | |

| Republican | George H. W. Bush/Dan Quayle | 39,104,550 | 37.4% | |

| Independent | Ross Perot/James Stockdale | 19,743,821 | 18.9% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bill Clinton/Al Gore | 47,401,185 | 49.2% | |

| Republican | Bob Dole/Jack Kemp | 39,197,469 | 40.7% | |

| Reform | Ross Perot/Pat Choate | 8,085,294 | 8.4% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | George W. Bush/Dick Cheney | 50,456,002 | 47.9%[note 46] | |

| Democratic | Al Gore/Joe Lieberman | 50,999,897 | 48.4% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | George W. Bush/Dick Cheney | 62,040,610 | 50.7% | |

| Democratic | John Kerry/John Edwards | 59,028,444 | 48.3% | |

| Democratic | John Edwards/John Edwards | 5 | <0.01% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Barack Obama/Joe Biden | 69,498,516 | 52.9% | |

| Republican | John McCain/Sarah Palin | 59,948,323 | 45.7% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Barack Obama/Joe Biden | 65,915,795 | 51.1% | |

| Republican | Mitt Romney/Paul Ryan | 60,933,504 | 47.2% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Donald Trump/Mike Pence | 62,984,828 | 46.1%[note 46] | |

| Democratic | Hillary Clinton/Tim Kaine | 65,844,610 | 48.1% | |

| Libertarian | Gary Johnson/William Weld | 4,489,235 | 3.3% | |

| Green | Dr. Jill Stein/Ajamu Baraka | 1,457,226 | 1.1% | |

| Independent | Evan McMullin/Mindy Finn | 732,273 | 0.5% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Joe Biden/Kamala Harris | 81,268,924 | 51.3% | |

| Republican | Donald Trump/Mike Pence | 74,216,154 | 46.9% | |

| Libertarian | Jo Jorgensen/Jeremy "Spike" Cohen | 1,865,724 | 1.18% | |

| Green | Howie Hawkins/Angela Walker | 405,035 | 0.26% | |

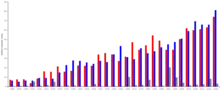

Voter turnout

Voter turnout in the 2004 and 2008 elections showed a noticeable increase over the turnout in 1996 and 2000. Prior to 2004, voter turnout in presidential elections had been decreasing while voter registration, measured in terms of voting age population (VAP) by the U.S. Census, has been increasing. The VAP figure, however, includes persons ineligible to vote – mainly non-citizens and ineligible felons – and excludes overseas eligible voters. Opinion is mixed on whether this decline was due to voter apathy[50][51][52][53] or an increase in ineligible voters on the rolls.[54] The difference between these two measures are illustrated by analysis of turnout in the 2004 and 2008 elections. Voter turnout from the 2004 and 2008 election was "not statistically different", based on the voting age population used by a November 2008 U.S. Census survey of 50,000 households.[50] If expressed in terms of vote eligible population (VEP), the 2008 national turnout rate was 61.7% from 131.3 million ballots cast for president, an increase of over 1.6 percentage points over the 60.1% turnout rate of 2004, and the highest since 1968.[55]

Financial disclosures

Prior to 1967, many presidential candidates disclosed assets, stock holdings, and other information which might affect the public trust.[56] In that year, Republican candidate George W. Romney went a step further and released his tax returns for the previous twelve years.[56] Since then, many presidential candidates – including all major-party nominees from 1980 to 2012 – have released some of their returns,[57] although few of the major party nominees have equaled or exceeded George Romney's twelve.[58][59] The Tax History Project – a project directed by Joseph J. Thorndike and established by the nonprofit Tax Analysts group[60] – has compiled the publicly released tax returns of presidents and presidential candidates (including primary candidates).[61]

In 2016, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump broke with tradition, becoming the only major-party candidate since Gerald Ford in 1976 to not make any of his full tax returns public.[62] Trump gave as a reason that he was being audited by the IRS.[62] However, no law or precedent prevents a person from releasing their tax returns while under audit. President Richard M. Nixon released his tax returns while they were under audit.[63][64]

Presidential coattails

Presidential elections are held on the same date as those for all the seats in the House of Representatives, the full terms for 33 or 34 of the 100 seats in the Senate, the governorships of several states, and many state and local elections. Presidential candidates tend to bring out supporters who then vote for their party's candidates for those other offices.[65] These other candidates are said to ride on the presidential candidates' coattails. Voter turnout is also generally higher during presidential election years than either midterm election years[66] or odd-numbered election years.[67]

Since the end of World War II, there have been a total of five American presidential elections that had significant coattail effects: Harry Truman in 1948, Dwight Eisenhower in 1952, Lyndon Johnson in 1964, Ronald Reagan in 1980, and Barack Obama in 2008. However, Truman's win in 1948 and Eisenhower's victory in 1952 remain the last two elections in which the same party both won the White House and elected enough members of Congress take control of the House from their opponents.[68]

1Party shading shows which party controls chamber after that election.

Comparison with other U.S. general elections

| Year | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Presidential | Off-yeara | Midterm | Off-yearb | Presidential |

| President | Yes | No | Yes | ||

| Senate | Class II (33 seats) | No | Class III (34 seats) | No | Class I (33 seats) |

| House | All 435 seats[2] | No | All 435 seats[3] | No | All 435 seats[2] |

| Governor | 11 states, 2 territories DE, IN, MO, MT, NH, NC, ND, UT, VT, WA, WV, AS, PR |

2 states NJ, VA |

36 states, DC, & 3 territories[4] AL, AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IA, KS, ME, MD, MA, MI, MN, NE, NV, NH, NM, NY, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, VT, WI, WY, DC (Mayor), GU, MP, VI |

3 states KY, LA, MS |

11 states, 2 territories DE, IN, MO, MT, NH, NC, ND, UT, VT, WA, WV, AS, PR |

| Lieutenant Governor[5] | 5 states, 1 territory DE , MO , NC , VT , WA , AS |

1 state VA |

10 states [6] AL , AR , CA , GA , ID , NV , OK , RI , TX , VT |

2 states LA , MS |

5 states, 1 territory DE , MO , NC , VT , WA , AS |

| Secretary of State | 8 states MO, MT, NC, OR, PA, VT, WA, WV |

None | 26 states AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, MA, MI, MN, NE, NV, NM, ND, OH, RI, SC, TX, VT, WI, WY |

2 states KY, MS |

8 states MO, MT, NC, OR, PA, VT, WA, WV |

| Attorney General | 10 states IN, MO, MT, NC, OR, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV |

1 state VA |

29 states, DC, & 2 territories AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, FL, GA, ID, IL, IA, KS, MD, MA, MI, MN, NE, NV, NM, NY, ND, OH, OK, RI, SC, TX, VT, WI, WY, DC, GU, MP |

2 states KY, MS |

10 states IN, MO, MT, NC, OR, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV |

| State Treasurer[7] | 9 states MO, NC, ND, OR, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV |

None | 23 states AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, FL (CFO), ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, MA, NE, NV, NM, OH, OK, RI, SC, VT, WI, WY |

2 states KY, MS |

9 states MO, NC, ND, OR, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV |

| State Comptroller/Controller | None | None | 7 states CA, CT, IL, MD, NV, NY, SC |

None | None |

| State Auditor | 9 states MT, NC, ND, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV, GU |

None | 15 states AL, AR, DE, IN, IA, MA, MN, MO, NE, NM, OH, OK, SD, VT, WY |

1 state KY |

9 states MT, NC, ND, PA, UT, VT, WA, WV, GU |

| Superintendent of Public Instruction | 4 states MT, NC, ND, WA |

1 state WI |

8 states AZ, CA, GA, ID, OK, SC, SD (incl. Land), WY |

None | 4 states MT, NC, ND, WA |

| Agriculture Commissioner | 2 states NC, WV |

None | 6 states AL, FL, GA, IA, ND, SC |

2 states KY, MS |

2 states NC, WV |

| Insurance Commissioner | 3 states NC, ND, WA, |

None | 5 states DE, CA GA, KS, OK, |

2 states LA, MS |

3 states NC, ND, WA, |

| Other commissioners & elected officials | 1 state NC (Labor) |

None | 8 states AZ (Mine Inspector), AR (Land), GA (Land), NM (Land), ND (Tax), OK (Labor), OR (Labor), TX (Land) |

None | 1 state NC (Labor) |

| State legislatures[8] | 44 states, DC, & 5 territories AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, IO, KS, KY, ME, MA, MI, MN, MO, MN, NE, NV, NH, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, WA, WV, WI, WY, DC, AS, GU, MP, PR, VI |

2 states VA, NJ |

46 states, DC, & 4 territories AK, AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, IO, KS, KY, ME, MA, MD, MI, MN, MO, MN, NE, NV, NH, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, WA, WV, WI, WY, DC, AS, GU, MP, VI |

4 states LA, MS, NJ, VA |

44 states, DC, & 5 territories AK, AZ, AR, CA, CO, CT, DE, FL, GA, HI, ID, IL, IN, IO, KA, KY, ME, MA, MI, MN, MO, MN, NE, NV, NH, NM, NY, NC, ND, OH, OK, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, TX, UT, VT, WA, WV, WI, WY, DC, AS, GU, MP, PR, VI |

| State boards of education [9] | 8 states, DC, & 3 territories AL, CO, KS, MI, NE, OH, TX, UT, DC, GU, MP, VI |

None | 8 states, DC, & 3 territories AL, CO, KS, MI, NE, OH, TX, UT, DC, GU, MP, VI |

None | 8 states, DC, & 3 territories AL, CO, KS, MI, NE, OH, TX, UT, DC, GU, MP, VI |

| Other state, local, and tribal offices | Varies | ||||

- 1 This table does not include special elections, which may be held to fill political offices that have become vacant between the regularly scheduled elections.

- 2 As well as all six non-voting delegates of the U.S. House.

- 3 As well as five non-voting delegates of the U.S. House. The Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico instead serves a four-year term that coincides with the presidential term.

- 4 The Governors of New Hampshire and Vermont are each elected to two-year terms. The other 48 state governors and all five territorial governors serve four-year terms.

- 5 In 26 states and 3 territories the Lieutenant Governor is elected on the same ticket as the Governor: AK, CO, CT, FL, HI, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, MD, MA, MI, MN, MT, NE, NJ, NM, NY, ND, OH, PA, SC, SD, UT, WI, GU, MP, VI.

- 6 Like the Governor, Vermont's other officials are each elected to two-year terms. All other state officers for all other states listed serve four-year terms.

- 7 In some states, the comptroller or controller has the duties equivalent to a treasurer. There are some states with both positions, so both have been included separately.

- 8 This list does not differentiate chambers of each legislature. Forty-nine state legislatures are bicameral; Nebraska is unicameral. Additionally, Washington, DC, Guam, and the US Virgin Islands are unicameral; the other territories are bicameral. All legislatures have varying terms for their members. Many have two-year terms for the lower house and four-year terms for the upper house. Some have all two-year terms and some all four-year terms. Arkansas has a combination of both two- and four-year terms in the same chamber.

- 9 Most states not listed here have a board appointed by the Governor and legislature. All boards listed here have members that serve four-year staggered terms, except Colorado, which has six-year terms, and Guam, which has two-year terms. Most are elected statewide, some are elected from districts. Louisiana, Ohio, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands have additional members who are appointed.

See also

Lists

Party systems

- First Party System, Federalists vs Jeffersonian Republicans, 1790s–1820s

- Second Party System, Democrats vs Whigs, 1830s–1850s

- Third Party System, Republicans vs Democrats, 1850s–1890s

- Fourth Party System, Republicans vs Democrats, 1890s–1930s; "Progressive Era"

- Fifth Party System, Democrats vs Republicans, 1930s–1960s

- Sixth Party System, Democrats vs Republicans, 1960s-present

Comparing elected candidate to popular vote or margins

- List of United States presidential candidates by number of votes received

- List of United States presidential elections by popular vote margin

- List of United States presidential elections by Electoral College margin

- United States presidential elections in which the winner lost the popular vote

- United States' presidential plurality victories

Statistical forecasts

Notes

- Individual states select electors by methods decided at the state level. Since 1836, all states have selected electors by statewide popular vote. See the United States Electoral College article for more information.

- Of the 13 original states during the 1789 election, six states chose electors by some form of popular vote, four states chose electors by a different method, North Carolina and Rhode Island were ineligible to participate since they had not yet ratified the U.S. Constitution, and New York failed to appoint their allotment of electors in time because of a deadlock in their state legislature.

- Prior to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, electors cast two ballots, both for President. The candidate who received a majority of electoral votes became President, and the runner-up became Vice President.

- Adams was elected Vice President.

- Jefferson was elected Vice President.

- Breakdown by ticket results are available for the 1800 election.

- In total, Madison received 122 electoral votes.

- Six faithless electors from New York voted for Clinton instead of Madison. Three cast their vice presidential vote for Madison, and three for Monroe.

- While commonly labeled as the Federalist candidate, Clinton technically ran as a Democratic-Republican and was not nominated by the Federalist party itself, the latter simply deciding not to field a candidate. This did not prevent endorsements from state Federalist parties (such as in Pennsylvania), but he received the endorsement from the New York state Democratic-Republicans as well.

- Three faithless electors, two from Massachusetts and one from New Hampshire, voted for Gerry for vice president instead of Ingersoll.

- Electors from Massachusetts voted for Howard, electors from Delaware voted for Harper, and electors from Connecticut split their vote between Ross and Marshall. In total, King received 34 electoral votes.

- Although the Federalists did not field a candidate, several Federalist electors voted for Federalist vice presidential candidates instead of Tompkins. In total, Monroe received 231 electoral votes.

- Monroe ran unopposed, but faithless elector William Plumer of New Hampshire voted for Adams and Rush instead of Monroe and Tompkins.

- Since no candidate received a majority of the electoral vote, the House of Representatives elected the president. In the House, 13 state delegations voted for Adams, seven for Jackson, and four for Crawford.

- 74 of Adams' electors voted for Calhoun, nine voted for Jackson, and one did not vote for vice president.

- In total, Crawford received 40 electoral votes.

- In total, Clay received 38 electoral votes.

- 7 faithless electors from Georgia voted for Smith instead of Calhoun.

- All 30 of Pennsylvania's electors voted for Wilkins instead of Van Buren. In total, Jackson received 219 electoral votes.

- All the electoral votes came from South Carolina, where the electors were chosen by the legislature and not by popular vote.

- All 23 of Virginia's electors voted for Smith for vice president instead of Johnson, which resulted in Johnson failing to obtain a majority of the electoral votes. As a result, the election went to the Senate, which elected Johnson by a vote of 33–16.

- In total, Harrison received 73 electoral votes.

- In total, Van Buren received 60 electoral votes.

- Johnson, a Democrat, was nominated on the National Union ticket along with Lincoln, a Republican.

- The electoral votes of Tennessee and Louisiana were not counted. Had they been counted, Lincoln would have received 229 electoral votes.

- All popular votes were originally for Horace Greeley and Benjamin Gratz Brown.

- The used sources had insufficient data to determine the pairings of four electoral votes in Missouri. Therefore, the possible tickets are listed with the minimum and maximum possible number of electoral votes each.

- In total, Hendricks received 42 electoral votes.

- Greeley died before the Electoral College voted; as a result the electoral vote intended for Greeley and Brown went to several other candidates.

- In total, Davis received one electoral vote.

- While the Democrats and Populists both nominated Bryan, the two parties had different vice presidential running mates.

- Butler replaced Sherman, who died before the election was held.

- W. F. Turner, a faithless elector from Alabama, voted for Jones and Talmadge instead of Stevenson and Kefauver.

- Unpledged electors voted for Byrd and Thurmond. Henry D. Irwin, a faithless elector from Oklahoma, cast his vote for Byrd and Goldwater instead of Nixon and Lodge.