1976 Italian general election

General elections were held in Italy on 20 June 1976, to select the Seventh Republican Parliament.[1] They were the first after the voting age was lowered to 18.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

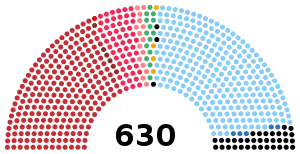

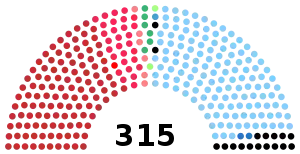

All 630 seats in the Chamber of Deputies 315 seats in the Senate | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 93.4% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

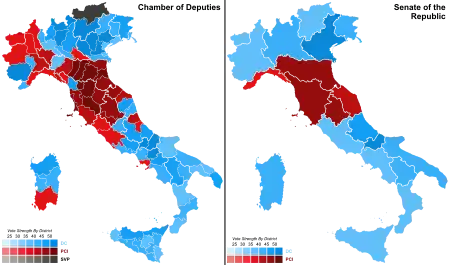

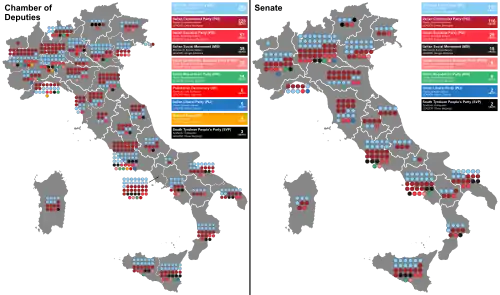

Results of the election in the Chamber and Senate. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If Christian Democracy remained stable with around 38% of votes, Enrico Berlinguer's Italian Communist Party made a great jump winning 7 points more than four years before: this result, which was quite homogeneous in the entire society because confirmed by the electors of the age-restricted Senate,[lower-alpha 1] began to show the possibility of a future change of the Italian government leadership. All minor parties lost many votes to the DC in the attempt to fight the Communist progress: between them, the historic Italian Liberal Party was nearly annihilated. Two new leftist forces made their debut in this election: the ultra-liberal Radical Party, which had led a successful referendum on divorce, and the far-left Trotskyist Proletarian Democracy.

Electoral system

The pure party-list proportional representation had traditionally become the electoral system for the Chamber of Deputies. Italian provinces were united in 32 constituencies, each electing a group of candidates. At constituency level, seats were divided between open lists using the largest remainder method with Imperiali quota. Remaining votes and seats were transferred at national level, where they were divided using the Hare quota, and automatically distributed to best losers into the local lists.

For the Senate, 237 single-seat constituencies were established, even if the assembly had risen to 315 members. The candidates needed a landslide victory of two thirds of votes to be elected, a goal which could be reached only by the German minorities in South Tirol. All remained votes and seats were grouped in party lists and regional constituencies, where a D'Hondt method was used: inside the lists, candidates with the best percentages were elected.

Historical background

Although the 1970s in Italy was marked by violence, it was also a time of great social and economic progress. Following the civil disturbances of the 1960s, Christian Democracy and its allies in government (including the Socialist Party) introduced a wide range of political, social, and economic reforms. Regional governments were introduced in the spring of 1970, with elected councils provided with the authority to legislate in areas like public works, town planning, social welfare, and health. Spending on the relatively poor South was significantly increased, while new laws relating to index-linked pay, public housing, and pension provision were also passed. In 1975, a law was passed entitling redundant workers to receive at least 80% of their previous salary for up to a year from a state insurance fund.[2] Living standards also continued to rise, with wages going up by an average of about 25% a year from the early 1970s onwards, and between 1969 and 1978, average real wages rose by 72%. Various fringe benefits were raised to the extent that they amounted to an additional 50% to 60% on wages, the highest in any country in the Western world. In addition, working hours were reduced so that by the end of the decade they were lower than any other country apart from Belgium. Some categories of workers who were laid off received generous unemployment compensation which represented only a little less than full wages, often years beyond eligibility. Initially, these benefits were primarily enjoyed by industrial workers in northern Italy where the “Hot Autumn” had its greatest impact, but these benefits soon spread to other categories of workers in other areas. In 1975, the escalator clause was strengthened in wage contracts, providing a high proportion of workers with nearly 100% indexation, with quarterly revisions, thereby increasing wages nearly as fast as prices.

A statute of worker’s rights that was drafted and pushed into enactment in 1970 by the Socialist labour minister Giacomo Brodolini, greatly strengthened the authority of the trade unions in the factories, outlawed dismissal without just cause, guaranteed freedom of assembly and speech on the shop floor, forbade employers to keep records of the union or political affiliations of their workers, and prohibited hiring except through the state employment office.[3]

In 1973, the Italian Communist Party's General Secretary Enrico Berlinguer launched a proposal for a "democratic alliance" with the Christian Democracy, embraced by Aldo Moro. This alliance was inspired by the Allende Government in Chile, that was composed by a left-wing coalition Popular Unity and supported by the Christian Democratic Party. After the Chilean coup of the same year, there was an approach between PCI and DC, that became a political alliance in 1976. In this time, the Berlinguer's PCI attempted to distance his party from the USSR, with the launch of the "Eurocommunism" along with the Spanish Communist Party and the French Communist Party.

In July 1975, a Christian leftist, Benigno Zaccagnini, became the new Secretary of Christian Democracy.

Parties and leaders

Results

Faced with the rise of the PCI, many centrist politicians and businessmen began to think how to avoid the possibility of a Communist victory that could turn Italy into a Soviet-aligned State. The DC leadership thought to gradually involve the Communists in governmental policies so as to moderate their aims, as had been done with the Socialists previously. The man who was chosen to lead this attempt did not belong to the leftist wing of the DC, as had happened with the PSI moderation effort, but the moderate leader and former-PM Giulio Andreotti, so as to balance the situation and calm the markets. The first government reliant on support from the communists was thus formed, when the PCI decided to grant its external support. However this process, called National Solidarity, was dramatically ended by the terrorist attacks of the Red Brigades, which saw the kidnapping and murder of former-PM Aldo Moro. The country was shocked by these killings, and the Communists returned to full opposition. Giulio Andreotti's subsequent attempt to form a classic centre-left government with the Socialists failed, and a new general election was called for 1979.

Chamber of Deputies

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy (DC) | 14,209,519 | 38.71 | 262 | −4 | |

| Italian Communist Party (PCI) | 12,614,650 | 34.37 | 228 | +49 | |

| Italian Socialist Party (PSI) | 3,540,309 | 9.64 | 57 | −4 | |

| Italian Social Movement (MSI) | 2,238,339 | 6.10 | 35 | −21 | |

| Italian Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) | 1,239,492 | 3.38 | 15 | −14 | |

| Italian Republican Party (PRI) | 1,135,546 | 3.09 | 14 | −1 | |

| Proletarian Democracy (DP) | 557,025 | 1.52 | 6 | New | |

| Italian Liberal Party (PLI) | 480,122 | 1.31 | 5 | −15 | |

| Radical Party (PR) | 394,439 | 1.07 | 4 | New | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 184,375 | 0.50 | 3 | ±0 | |

| PCI – PSI – PdUP | 26,748 | 0.07 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Others | 87,014 | 0.24 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,045,512 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 37,755,090 | 100 | 630 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 40,426,658 | 93.39 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

Senate of the Republic

| |||||

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democracy (DC) | 12,227,353 | 38.88 | 135 | ±0 | |

| Italian Communist Party (PCI) | 10,637,772 | 33.83 | 116 | +22 | |

| Italian Socialist Party (PSI) | 3,208,164 | 10.20 | 29 | −4 | |

| Italian Social Movement (MSI) | 2,086,430 | 6.63 | 15 | −11 | |

| Italian Democratic Socialist Party (PSDI) | 974,940 | 3.10 | 6 | −5 | |

| Italian Republican Party (PRI) | 846,415 | 2.69 | 6 | +1 | |

| Italian Liberal Party (PLI) | 438,265 | 1.39 | 2 | −6 | |

| PLI – PRI – PSDI | 334,898 | 1.06 | 2 | ±0 | |

| Radical Party (PR) | 265,947 | 0.85 | 0 | New | |

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 158,584 | 0.50 | 2 | ±0 | |

| Proletarian Democracy (DP) | 78,170 | 0.25 | 0 | New | |

| PCI – PSI | 52,922 | 0.17 | 1 | +1 | |

| PLI – PRI | 51,353 | 0.16 | 0 | ±0 | |

| DC – RV – UV – UVP – PRI | 22,917 | 0.07 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Others | 65,301 | 0.22 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,888,027 | – | – | – | |

| Total | 32,621,581 | 100 | 315 | ±0 | |

| Registered voters/turnout | 34,928,214 | 93.4 | – | – | |

| Source: Ministry of the Interior | |||||

Notes

- While the electorate for the House had been expanded from 21-year-old citizens to 18, it had remained unvaried at 25 for the Senate.

References

- Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1048 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796 by Christopher Duggan

- Italy, a difficult democracy: a survey of Italian politics by Frederic Spotts and Theodor Wieser