Aljafería

The Aljafería Palace (Spanish: Palacio de la Aljafería; Arabic: قصر الجعفرية, tr. Qaṣr al-Jaʿfariyah) is a fortified medieval palace built during the second half of the 11th century in the Taifa of Zaragoza in Al-Andalus, present day Zaragoza, Aragon, Spain. It was the residence of the Banu Hud dynasty during the era of Abu Jaffar Al-Muqtadir. The palace reflects the splendour attained by the Taifa of Zaragoza at the height of its grandeur. It currently contains the Cortes (regional parliament) of the autonomous community of Aragon.[1]

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Zaragoza, Aragon, Spain |

| Part of | Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 378 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th session) |

| Extensions | 2001 |

| Coordinates | 41°39′23″N 0°53′48″W |

Location in Aragon and Spain  Aljafería (Spain) | |

The structure holds unique importance in that it is the only conserved testimony of a large building of Spanish Islamic architecture of the era of the Taifas (independent kingdoms). The Aljaferia, along with the Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba and the Alhambra are the three best examples of Hispano-Muslim architecture and have special legal protection. In 2001, the original restored structures of the Aljafería were included in the Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon, a World Heritage Site.[2]

The solutions adopted in the ornamentation of the Aljafería, such as the use of mixtilinear arcs and springers, the extension of arabesque in large area, and the schematisation and progressive abstraction of the yeserias of a vegetal nature, decisively influenced Almoravid and Almohad art in the Iberian Peninsula. The transition of the decoration towards more geometric motifs is at the basis of Nasrid art.

After the reconquest of Zaragoza in 1118 by Alfonso I of Aragón, it became the residence of the Christian kings of the Kingdom of Aragón. It was used as a royal residence by Peter IV of Aragón (1319-1387) and later, on the main floor, the reform was carried out that converted these rooms into the palace of the Catholic Monarchs in 1492. In 1593 it underwent another restructuring that would turn it into a military fortress, first according to Renaissance designs (which today can be seen in its surroundings, moat and gardens) and later for quartering military regiments. It underwent continuous restructuring and damage, especially with the Sieges of Zaragoza of the Peninsular War, until, unusually for historical buildings in Spain, it was finally restored in the 20th century.

The palace was built outside Zaragoza's Roman walls, in the plain of the saría. With urban expansion over the centuries, it is now inside the city.

History

Most Aljaferiá was completed by Abu Jaffar Al-Muqtadir during the Banu Hud reign in the taifa of Zaragoza, in the 11th century.

After the reconquest of Zaragoza in 1118 by Alfonso of Aragon "the Battler", the Aljafería became the residence of the Christian kings of Aragon, becoming the main focus of the Aragonese Mudejar diffusion. It was used as a royal residence by Peter IV of Aragon "the Ceremonious" and later, on the main floor, was carried out the reform that turned these paradors into the palace of the Catholic Monarchs in 1492. In 1593 it underwent another reform that would make it into a military fortress, first according to Renaissance designs (which today can be seen in their surroundings, pit and gardens) and later as a quarters of military regiments. It underwent continuous reforms and major damage, especially during the Sieges of Saragossa of the Napoleonic French invasion, until finally it was restored in the second half of the twentieth century and currently houses the Parliament of Aragon.

Originally the building was outside the Roman walls, in the plain of the Saría or place where the Muslims developed the military fanfare known as La Almozara. With the urban expansion through the years, the building has remained within the city. There is a small space with landscaped garden environment.

Troubadour Tower

The oldest construction of the Aljafería is today known as the Troubadour Tower. The tower received this name from Antonio Garcia Gutierrez’s 1836 romantic drama The Troubadour, based largely at the palace. This drama became the libretto for Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Il trovatore in 1853.

.jpg.webp)

The tower is a defensive structure, with a quadrangular base and five levels which date back to the end of the 9th century AD, in the period governed by the first Banu Tujib, Muhammad Alanqur, who was named after Muhammad I of Córdoba, independent Emir of Cordoba. According to Cabañero Subiza (1998) the Tower was built in the second half of the 10th century.[3] In its lower part, the tower contains vestiges of the beginning of the heavy walls of alabaster ashlar bond masonry, and continues upwards with plank lining of simple plaster and lime concrete, which is a thinner substance for reaching greater heights. The exterior does not reflect the division of the five internal floors and appears as an enormous prism, broken by narrow embrasures. Access to the interior was gained through a small door at such height that it was only possible to enter by means of a portable ladder. Its initial function was, by all indications, military.

The first level conserves the building structure of the 9th century and shelters two separated naves and six sections, which are separated by means of two cruciform pillars and divided by lowered horseshoe arcs. In spite of its simplicity, they form a balanced space and could be used as baths.

The second floor repeats the same spatial scheme of the previous one, and remains of a Muslim factory of the 11th century in the brick canvases, which indicates that, from the 14th century something similar happens with the appearance of the last two floors, of Mudéjar invoice, and whose construction would be due to the construction of the palace of Peter IV of Aragon, that is connected with the Tower of the Troubadour thanks to a corridor, and would be configured as tower of homage. The arches of these plants already reflect its Christian structure, because they are slightly pointed arches, and support unveiled roofs, but flat structures in wood.

Its function in the 9th and 10th centuries was the watch tower and defensive bastion. It was surrounded by a moat. It was later integrated by the Banu Hud family in the construction of the castle-palace of the Aljafería, constituting itself in one of the towers of the defensive framework of the outside north canvas. From the Spanish Reconquista, it continued being used like tower of the homage and in 1486 became dungeon of the Inquisition. As a tower-prison was also used in the 18th and 19th centuries, as demonstrated by the numerous graffiti inscribed there by the p2.

Moorish Taifal palace

The building of the palace – mostly made between 1065 and 1081—[4] was ordered by Abú Ja'far Ahmad ibn Sulaymán al-Muqtadir Billah, known by his honorary title of Al-Muqtadir (The powerful), second monarch of the Banu Hud dynasty, as a symbol of the power achieved by the Taifa of Zaragoza in the second half of the 11th century. The sultan himself called his palace "Qasr al-Surur" (Palace of the Joy) and to the throne room which he presided the receptions and embassies of the "Maylis al-Dahab" (Golden Hall) as it is testified in the following verses of the Sultan self:

Oh Palace of the Joy!, Oh Golden Hall!

Because of you, I reached the maximum of my wishes.

And even though in my kingdom I had nothing else,for me you are everything I could wish for.

The name of Aljafería is first documented in a text by Al-Yazzar as-Saraqusti (active between 1085 and 1100) – which also transmits the name of the architect of the Taifal palace, the Slav Al-Halifa Zuhayr—[4] and another from Ibn Idari of 1109, as a derivation from the pre-name of Al-Muqtadir, Abu Ya'far, and "Ya'far", "Al-Yafariyya", which evolved to "Aliafaria" and from there to "Aljafería".

The general layout of the whole palace adopts the archetype of the castles of the desert of Syria and Jordan of the first half of the 8th century (such as Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi,[5] Msatta, Jirbat al-Mafyar, and from the first Abbasid stage, the castle of Ujaydir) which were square-shaped and ultrasemicircular towers in its cloths, with a central tripartite space, which leaves three rectangular spaces of which the central one houses a courtyard with pools and, at the northern and southern ends of the same, the palatial rooms and the dependencies of daily life.

In the Aljafería, this castle-palace model is honored, whose noble zone is located in the central segment of its square plant, although the alignment of the sides of this plant is irregular. It is the central rectangle that houses the palatial dependencies, organized around a courtyard with cisterns in front of the north and south porticos to which the rooms and royal saloons are poured.

At the north and south ends are the porticos and room dependencies, and in the case of the Aljafería, the most important of these sectors is the north, that in origin was endowed with a second plant and had greater depth, besides being preceded by an open and profusely decorated column wall that stretched in two arms by two pavilions on its flanks and served as a theatrical porch to the throne room (the golden hall of the verses of Al-Muqtadir) located at the bottom. It produced a set of heights and cubic volumes beginning with the perpendicular corridors of the ends, it was emphasized by the presence of the height of the second floor and ended with the tower of the troubadour that offered its volume in the background to the look of a spectator located in the courtyard. All this, reflected also in the cistern, enhanced the royal area, which is corroborated by the presence at the eastern end of the northern border of a small private mosque with mihrab.

In the center of the northern wall of the interior of the Golden Hall was a blind arch – where the king stood – in whose thread was a very traditional geometric pattern imitating the latticework of the mihrab façade of the Mosque of Córdoba, building to which it was sought to emulate. In this way, from the courtyard, it appeared half-hidden by the plots of columns of both the archway of access to the Golden Hall and those of the immediate portico, which gave an appearance of latticework, an illusion of depth, which admired the visitor and lent splendor to the figure of the monarch.

In order to remember the appearance of the palace at the end of the 11th century, we must imagine that all the vegetal, geometric and epigraphic reliefs were polychromed in shades in which red and blue predominated for backgrounds and gold for reliefs, which, together with the soffits in alabaster with epigraphic decoration and the floors of white marble, gave the whole an aspect of great magnificence.

The various avatars suffered by the Aljafería, have made disappear from this layout of the 11th century a large part of the stuccos that made up the decoration and, with the construction of the palace of the Catholic Monarchs in 1492, the entire second floor, which broke the ends of the Taifal arches. In the current restoration, the original arabesques are observed in darker color and in white and smooth finishes the reconstruction of plaster of the decoration the arches, whose structure, however, remains undamaged.

The decoration of the walls of the Golden Hall has disappeared for the most part, although remains of its decoration are preserved in the Museo de Zaragoza and in the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid. Francisco Íñiguez began its restoration, restoring the decorations that existed in its places of origin and extracting complete emptyings of the arcades of the south portico.

These were the functions and aspect of the 11th century Banu Hud palace. Below are the most important parts of the building as they are today.

North side halls

In the north wall, the most important complex of buildings of the Banu Hud period is built, as it includes the Throne Room or Golden Hall and the small private mosque, located on the eastern side of the access portico that serves as an antechamber to the oratory). In its interior it houses a mihrab in the southeast corner, whose niche, therefore, is oriented in the direction of Mecca, as it happens in all the mosques except in the one of Córdoba.

The soils of the royal stays were of marble and walked them a plinth of alabaster. The capitels were of alabaster, except some of reused marble of Caliphate period. These rooms were surrounded by a band of epigraphic decoration with Kufic characters reproducing Quran surahs that alluded to the symbolic meaning of ornamentation. The surahs corresponding to these inscriptions have been deduced from the surviving fragments.

In two of these calligraphic reliefs can be the name of Al-Muqtadir, reason why the construction of the palace has been dated, at least in a first phase, between 1065 and 1080. They say verbatim "This [= the Aljafería] was ordered by Ahmed al-Muqtadir Billáh".

Golden Hall

The Golden Hall had at its ends east and west two rooms that were private bedrooms possibly of royal use. Today the bedroom of the western flank has been lost, which was used as a royal bedroom and also used the Aragonese kings until the 14th century.

Most of the yeserias of arabesques, which carpeted the walls of these stays with decorative panels plastered with plaster, as well as an alabaster base of two and a half meters high and the white marble floors of the original palace, have been lost. The remains that have been preserved, both in museums and the few that are in this royal hall, nevertheless allow to reconstruct the appearance of this polychrome decoration, which, in its day, should have been splendid.

Ceilings, wood carvings, reproduced the sky, and the whole room was an image of the cosmos, clothed with symbols of the power exercised over the celestial universe by the monarch of Saragossa, who thus appeared as heir to the caliphs.

The access to the Golden Hall is made through a canvas with three vanes. A very large central one, consisting of five double marble columns with very stylized Islamic alabaster capitals that support four mixtilinear arches, among which, in height, there are other simpler horseshoe.

Entrance portico to the Golden Hall

Towards the south, another dependence of similar size is poured that it pours to the courtyard by a portico of great polilobulated arcades. Again there is a tripartite space, and its east and west ends extend perpendicularly with two lateral galleries which are accessed by wide polyhedral lobes and which end at the end of their arms in separate pointed arches also polilobulated whose alfiz is decorated by complex laqueus and reliefs of arabesques.

This whole structure seeks an appearance of solemnity and majesty that the scant depth of these stays would not give a spectator to access the king's room. In addition, all the ornamentation of yeserias of the palace was polychrome in shades of blue and red in the back and gold in the arabesques. Among the filigrees is the representation of a bird, an unusual zoomorphic figure in Islamic art that could represent a pigeon, a pheasant or a symbol of the king as winged.

The traces of interlocking mixtilinear arches are characteristic of this palace and are given for the first time in the Aljafería, from where they will be diffused to the future Islamic constructions.

On the eastern side of the portico is a sacred space, the mosque, which is accessed through a portal inspired by caliph art and described below.

Mosque and the oratory

At the eastern end of the entrance portico to the Golden Hall, there is a small mosque or private oratory for use by the monarch and his courtiers.[6] It is accessed through a portal that ends in a horseshoe arch inspired by the Mosque of Córdoba but with S-shaped springers, a novelty that will imitate the Almoravid art and Nasrid art. This arch rests on two columns with capitals of leaves very geometricals, in the line of the realizations Granadan art of solutions in Mocárabe. Its alfiz is profusely ornamented with vegetal decoration and on it is arranged a frieze of half-point arcs crossed.

Already inside the oratory there is a reduced space of square plant but with chamfered corners, that turns it into a false octagonal plant. In the southeast sector, oriented towards Mecca, is located the niche of the mihrab. The front of the mihrab is conformed by a very traditional horseshoe arch, with Cordoban shapes and alternating camouflage threads, some decorated with vegetal reliefs and other smooth ones (although originally they were decorated with pictorial decoration), reminiscent of the mihrab thread of the Mosque of Córdoba, only what were rich materials (mosaics and Byzantine bricklayers) in Zaragoza, with greater material poverty than the Caliphian Córdoba, are plaster stucco and polychrome, the latter having been lost in almost the entire Palace. Continuing with the arch of the portal, an alfiz framed its back, in whose curved triangles two mirrored rosettes are recessed, as is the dome of the interior of the mihrab.

The rest of the walls of the mosque are decorated with blind mixtilineal arches linked and decorated throughout the surface with vegetable arabesques of Caliph's inspiration. These arches lean on columns topped with capitals of slender basket. A slab of square marble slabs covers the bottom of the walls of the mosque.

All this is topped with a splendid theory of interlocking polyblocked arches, which, in this case, are not blind in their entirety, because those in the chamfered corners let now see the angles of the square plant structure. This gallery is the only one that conserves remains of the pictorial decoration of the 11th century, whose motives were rescued by Francisco Íñiguez Almech after removing the liming with which they were covered after the passage of the Aljafería to chapel. Unfortunately, this restorer, praiseworthy for having saved from the ruin of the monument, worked in an age of different criteria to the present ones, because he intended to restore all the elements to their original appearance. For this he repainted with acrylic paint the traces of Islamic remains, which makes this performance irreversible and, consequently, we will never see the, although very faded, original pigment.

The dome of the mosque was not preserved, because that is the height in which the palace of the Catholic Monarchs was built; However, the characteristic octagonal plant suggests that the solution should follow literally the existing ones in the maqsurah of the mosque of Córdoba, that is to say, a dome of semicircular arches that are interlaced forming an octagon in the center. The covering proposal of Francisco Íñiguez is, however, in this case, reversible, as it is a detachable dome of plaster. In 2006, Bernabé Cabañero Subiza, C. Lasa Gracia and J. L. Mateo Lázaro postulated that "the nerves of the vault [...] should have the section of horseshoe arches forming an eight-pointed star pattern with a dome agglomerated in the center, as those existing in the two domes of the transept of the Mosque of Córdoba.[7]

South side halls

Completing the tour of the 11th-century palace, one arrives at the south portico, which consists of an arcade on its southern flank that gives access to a portico with two lateral stays.

This portico was the vestibule of a great south hall that would have the same tripartite disposition of the existent one in the north side, and of which only the arcades of access of mixtilineal arches of geometric decoration remains. Perhaps in this southern sector the greatest daring in arches, through the interlocking of lobulated forms, mixtilinea, and the inclusion of small reliefs of shafts and capitals with exclusively ornamental function.

The complexity of laqueus, arabesques and carvings leads to a Baroque aesthetic, which is a prelude to the filigree of the art of the Alhambra and which are some of the most beautiful of all Al-Andalusian art.

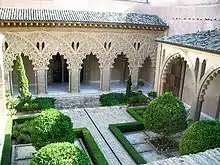

Courtyard of Santa Isabel

It is the open and landscaped space that unified the whole Taifal palace. To it would pour the north and south porticos, and probably rooms and outbuildings to the east and west of this central courtyard.

Its name comes from the birth in the Aljafería of the infanta Elizabeth of Aragon, that was in 1282 Queen of Portugal. The original pool of the south has been conserved, whereas the one of the north front, of the 14th century, has been covered with a wood floor. The restoration tried to give the courtyard the original splendor, and for that a marble floor was arranged in the corridors that surround the orange and flower garden.

The arcade that is contemplated looking towards the south portico is restored by means of the emptying of the original arcs that are deposited in the National Archaeological Museum of Madrid and in the Museo de Zaragoza . They suppose the greater audacity and distance for their innovation with respect to the caliphs models of the arcades of the north side.

According to Christian Ewert, who has studied for fifteen years the arches of the Aljafería, the more related to noble zones (Golden Hall and Mosque) are the ornaments of the arcades, more respect they have to the Córdoban tradition from which they leave.

Palace of Peter IV of Aragon "the Ceremonious"

After the taking of Saragossa by Alfonso the Battler in 1118, the Aljafería was habilitated like palace of the kings of Aragon and the church, not being substantially modified until the 14th century with the performance of Peter IV of Aragon "the Ceremonious".

This king extended the palatial dependencies in 1336 and had constructed the Church of San Martín in the entrance courtyard to the alcázar. In this time the use of the Aljafería is documented like place of departure of the route that took to Cathedral of the Savior of Zaragoza, where the Aragonese monarchs were solemnly crowned and they swore the Fueros of Aragon.

Chapel of San Martín

The chapel of San Martín takes advantage of the canvases of the northwest corner of the wall, to the point that one of its towers was used as sacristy and gave name to the courtyard that gives access to the Taifal enclosure.

The factory, of Gothic-Mudéjar style, consists of two naves of three sections each, in origin orientated to the east and supported in two pillars with semicolumns attached in the half of the faces of the pillar, whose section is remembered in the quadrilobed that shelter the shield of arms of the King of Aragon in the spandrels of the portal, that is already of the first decade of the 15th century and in which we will stop later.

The vaults of these naves, of simple rib vault, are lodged on formeros arches and pointed perpiaños arches, whereas the diagonals are of half point. At the corners of the vaults appear florets with the coat of arms of the Aragonese monarchy. Of its decoration only fragments of the pictorial covering and some mixtilineal arches are preserved directly inspired in the Muslim palace.

It emphasizes in the exterior the Mudéjar portal of brick referred to previously, built in the time of Martin of Aragon "the Humane" and opened in the last section of the south nave.

This portal is articulated by a carpanel arch very recessed, covered by another pointed of greater dimensions. Framing both, a double alfiz decorated with taqueado jaqués motifs forming lozenge cloths.

In the spandrels, as it was pointed out, two quadrilobed medallions appear that harbor shields with the image of the insignia of king of Aragon. In the resulting tympanum between the arches there is a band of interlocking mixtilineal blind arches, which again refer to the series of the Banu Hud palace. This strip is interrupted by a box that houses a newly incorporated relief.

The chapel was remodeled in the 18th century, placing a nave ahead of it and covering the Mudéjar portal previously described. The pillars and walls were refurbished and plastered to the Neoclassical style. All the reform was eliminated during the restorations of Francisco Íñiguez, although by the existing photographic documentation, it is known that there was a slender tower that now appears with a crenellated finish inspired by the aspect of the Mudéjar church, and in the 18th century culminated with a curious bulbous spire.

Mudéjar Palace

It is not an independent palace, but an extension of the Muslim palace that was still in use. Peter IV of Aragon tried to provide more spacious rooms, dining rooms and bedrooms to the Aljafería, because the Taifal bedrooms had remained small for the use of the Ceremonious.

These new rooms are grouped on the northern sector of the Al-Andalusian palace, at different levels of height. This new Mudéjar factory was extraordinarily respectful of the pre-existing construction, both in plan and elevation, and is made up of three large rectangular halls covered by extraordinary aljarfes or wooden mudéjar ceilings.

Also from this time is the western arcade of pointed arches of the Patio de Santa Isabel, intrados in lobed arcs, and a small bedroom of square plant and covered with an octagonal dome of wood and a curious door of entrance in pointed arc of lobed intrados circumscribed in a very fine alfiz, whose spandrel is decked out of arabesque. This door leads to a triple lodge of semicircular arches. The bedroom is located on the building block above the mosque.

Palace of the Catholic Monarchs

In the last years of the 15th century the Catholic Monarchs ordered to construct a palace for royal use on the north wing of the Al-Andalusian enclosure, configuring a second plant superposed to the one of the existing palace. The building broke the high parts of the Taifal stays, where inserted the beams that would support the new palace.

The works are dated between 1488 and 1495 and were followed by Mudéjar masters, maintained the tradition of Mudéjar bricklayers in the Aljafería.

The palace is accessed by climbing the noble staircase, a monumental building composed of two large sections with geometric yeserias gables illuminated by half-angled windows of small decoration of leaves and stems of Gothic roots and Mudéjar influences, topped in crochet on the key of the arches.

The grandiose ceiling, as in the rest of the palace buildings, is covered with superb cross-vaulted vaults arranged between the jácenas, and they are decorated with tempera painting with iconographic motifs related to the Catholic Monarchs: the yoke and the arrows alternate with squares of decoration in grisao of grotesques and candelieri, that announces the typical decoration of the Renaissance.

The stairs give access to a corridor in the first floor that communicates with the palatial dependencies proper. It opens to a gallery of columns of torso stem that rest on shoes with anthropomorphic reliefs at their ends. To support this viewpoint and the rest of the new dependencies it was necessary to section the high areas of the Taifal halls of the 11th century and to have before the north portico five powerful octagonal pillars that, next to some archways pointed behind them, form a new antepartum that unites The two Al-Andalusian perpendicular pavilions above.

It emphasizes the main entrance to the Throne Room: a trilobed recessed arch with a five-lobed tympanum, at the center of which is represented the coat of arms of the monarchy of the Catholic Monarchs, which includes the coats of arms of the kingdoms of Castile, León, Aragon, Sicily and Granada, supported by two lieutenant lions. The rest of the decorative field is finished with a delicate vegetal ornamentation of stamped invoice, which reappears in the capitals of the jambs. The entire portal is made of hardened plaster, which is the predominant material in the interior of the Aljafería, as Mudéjar craftsmen perpetuate the materials and techniques that are common in Islam.

In the same wall, two large windows of triple mixtilineal arc with shutters on their keys are escorted by the entrance, thanks to which the inner space of the royal rooms is illuminated.

Once the space of the gallery is crossed, several rooms are arranged that precede to the great Throne Room, that are denominated "rooms of the lost steps". These are three small rooms of square plan communicated to each other by big windows shut with lattices that give to the Patio de San Martín, and that served as waiting rooms for those who were to be received in audience by the kings.

In our days only two are visible, because the third one was closed when replacing the dome of the mosque. Its roof was moved to a room adjoining the Throne Room.

One of the most valuable elements of these rooms are their floors, which originally were square azulejos and hexagonal ceramic alfardones glazed in colors, forming capricious borders. They were made in the historic pottery of Loza de Muel at the end of the 15th century. From the preserved fragments has been set to restore the entire floor with ceramics that mimics the shape and layout of the former floor, but not its quality glazed reflections.

The other remarkable element is its excellent Mudéjar-Catholic Monarchs style roofs, constituted by three magnificent taujeles of Aragonese Mudéjar carpenters. These ceilings present geometric reticules of wood later carved, painted and gilded with gold leaf, whose moldings show the well-known heraldic motifs of the Catholic Monarchs: the yoke, the arrows and the Gordian knot united to the classic motto "Tanto monta" (both mounts to undo the Gordian knot), both mounts to cut it as to untie it, according to the well-known anecdote attributed to Alexander the Great), as well as a good number of leaflet florets finished with pendant (pinjante) pineapples.

Throne Room

More complex and difficult to describe is the magnificence and sumptuousness of the ceiling that covers the Throne Room. Its dimensions are very considerable (20 metres (66 feet) in length by 8 in width) and its Artesonado coffered ceiling is supported by thick beams and sleepers decorated with laqueus that at intersections form eight-pointed stars, while generating thirty large and deep square coffins.

Inside these coffins are inscribed octagons with a central flower of curly leaf that finish in large hanging pine cones that symbolize fertility and immortality. This ceiling was reflected in the ground, which reproduces the thirty squares with their respective octagons inscribed.

Under the Artesonado coffered ceiling there is an airy gallery of passable arches and with open windows, from which the guests could contemplate the royal ceremonies. Finally, all this structure is based on an arrocabe with moldings in carved navicella with vegetal and zoomorphic themes (cardina, branches, fruits of the vine, winged dragons, fantastic animals...), and in the frieze that surrounds the whole perimeter of the room, there appears a legend of Gothic calligraphy that reads:

Ferdinandus, Hispaniarum, Siciliae, Corsicae, Balearumque rex, principum optimus, prudens, strenuus, pius, constans, iustus, felix, et Helisabeth regina, religione et animi magnitudine supra mulierem, insigni coniuges, auxiliante Christo, victoriosissimi, post liberatam a mauris Bethycam, pulso veteri feroque hoste, hoc opus construendum curarunt, anno salutis MCCCCLXXXXII.

The translation of this inscription is:

Ferdinand, King of the Spains, Sicily, Corsica and Balearic, the best one of the princes, prudent, courageous, pious, constant, just, jocose, and Isabella, queen, superior to all woman because her pity and greatness of spirit, distinguished matrimony very victorious with the help of Christ, after liberating Andalusia from Moors, expelled the old and ferocious enemy, ordered to build this work the year of the Salvation of 1492.

Early-Modern and Modern times

At the beginning of 1486, the area of the Patio de San Martín was destined to the headquarters of the Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition and facilities were installed adjacent to the courtyard to house the officers of this organization. It is likely that this is the origin of the use as a prison of the Tower of the Troubadour.

The new function (which lasted until the early-18th century) triggered an event that would culminate in a reform project undertaken under the mandate of Philip II of Spain by which he would henceforth become a military base. In 1591, in the events known as the Alterations of Aragon, the persecuted secretary of King Philip II, Antonio Pérez took refuge at the Privilege of Manifestation contemplated by the Fuero of Aragon in order to elude the imperial troops. However, the Tribunal of the Inquisition had jurisdiction over all the fueros of the kingdoms, and, for that reason, he was held in a cell of the inquisitorial headquarters of the Aljafería, which provoked an uprising of the people before what they considered a violation of the foral law, and they went to the assault of the Aljafería to rescue him. After the forceful action of the royal army, the revolt was put down, and Philip II decided to consolidate the Aljafería as a fortified citadel under his authority to prevent similar revolts.

The design of the work, which consisted of a military construction, was entrusted to the Italian-Sienese military engineer, Tiburzio Spannocchi. He constructed a set of habitat attached to the south and east walls that hid the ultrasemicircular turrets in its interior, although in the east façade it did not affect those who flanked the entrance door and these onwards. Surrounding the entire building, a marlon wall was erected leaving inside a round space and ending at its four corners in four pentagonal bastions, whose starts can be seen today. The entire complex was surrounded by a moat twenty meters wide, which was saved by two drawbridges on the east and north flanks.

The Aljafería remained without substantial changes until 1705, in which due to the War of Spanish Succession it was lodging of two companies of French troops that took to a regrowth of the parapets of the low wall of the pit effected by the military engineer Dezveheforz.

But the decisive transformation as quartering took place in 1772 at the initiative of Charles III of Spain, in which all the facades were remodeled to the way in which the western one is presently, and that the interior spaces were used as dependencies for the soldiers and officers who were staying in the building. In the western third of the palace was set up a large courtyard to which the rooms of the different companies, made with simplicity and functionality, following the rationalist spirit of the second half of the 18th century and the practical purpose to which the constructed areas were destined so. Only the addition in 1862 by Isabella II of Spain of four Gothic-Revival towers, of which the ones located in the north-western and south-western corner, stand today.

It was precisely in the mid-19th century when Mariano Nougués Secall raised the alarm due to the deterioration of the al-Andalusian and Mudéjar remains of the palace in its 1845 report entitled Descripción e historia del castillo de la Aljafería, a rigorous study in which it was urged to preserve this valuable historical-artistic ensemble. Even the Queen Isabella II of Spain contributed funds for the restoration, and a commission was created in 1848 to undertake it; but in 1862 the Aljafería passed from property of the Royal Patrimony to the Ministry of the War, which aborted its restoration and would aggravate the damages produced.

The deterioration still continued until that since 1947 was being integrally restored by the architect Francisco Íñiguez Almech, the restoration was started and completed during the government of Francisco Franco.

In the 1960s it was used as a military barracks, and the decoration was covered with plaster with the aim of protecting it.

In 1984 the regional parliamentary commission created to find a definitive headquarters to the Cortes of Aragon recommended locating the autonomous parliament into the Aljafería Palace and the City Council of Zaragoza (owner of the building) agreed to transfer the council to a section of the building for a period of 99 years.[14]In this way the section was adapted and the building again restored by Ángel Peropadre, Juan Antonio Souto (archaeological work), Luis Franco Lahoz and Mariano Pemán Gavín, who carried out for the location of the headquarters of the Cortes de Aragon. The Aljafería was finally declared an artistic and historical monument in 1998 with presence of prince Philip VI.

In 1593 Philip II of Spain expanded the site of the Aljafería by building a citadel around it (besides the moat), as seen in this contemporary drawing.[15] Archivo General de Simancas

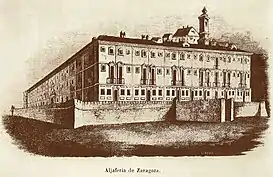

In 1593 Philip II of Spain expanded the site of the Aljafería by building a citadel around it (besides the moat), as seen in this contemporary drawing.[15] Archivo General de Simancas A view of the Aljafería in 1848 before it was restored.

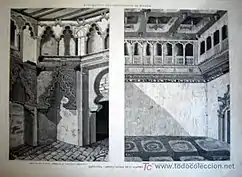

A view of the Aljafería in 1848 before it was restored. Remains of the Interior of the Aljafería in 1879 before it was restored.

Remains of the Interior of the Aljafería in 1879 before it was restored. Remains of the Interior of the Aljafería before the large restoration, photo of 1889.

Remains of the Interior of the Aljafería before the large restoration, photo of 1889. Detail of the interior of the mosque. The Aljafería before the large restoration, photo of 1891.

Detail of the interior of the mosque. The Aljafería before the large restoration, photo of 1891. Ceiling of the Grand Hall of the Palace of the Catholic Monarchs viewed in 1890, before the restoration.

Ceiling of the Grand Hall of the Palace of the Catholic Monarchs viewed in 1890, before the restoration.

References

- Planet, Lonely. "Aljafería in Zaragoza, Spain". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- "Mudéjar Architecture of Aragon". UNESCO World Heritage Center.

- Cabañero Subiza (1998), p. 84.

- Bernabé Cabañero Subiza, op. cit., 1998, page 87.

- image of the palace of Qasr al-Hayr al-Sharqi of Syria.

- "Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum - monument_isl_es_mon01_4_en". www.discoverislamicart.org. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- Bernabé Cabañero Subiza, C. Lasa Gracia y J. L. Mateo Lázaro, "The Aljafería of Zaragoza as an imitation and culmination of the architectural and decorative scheme of the Aljama Mosque of Córdoba", Artigrama, n.º 21, 2006, pág. 275. Apud. María Pilar Biel Ibáñez, 'New news on the Palace of the Aljafería', in Guillermo Fatás (dir.), Guía histórico-artística de Zaragoza, 4ª ed. revised and extended, City Council of Zaragoza, 2008, p. 717. ISBN 978-84-7820-948-4.

- turismodezaragoza.es, December 15, 2017 https://www.turismodezaragoza.es/ciudad/patrimonio/mudejar/palacio-de-la-aljaferia-zaragoza.html Missing or empty

|title=(help) - José Antonio Tolosa, "THE ALJAFERÍA (ZARAGOZA). Palacio mudéjar -Patio de Santa Isabel-", aragonmudejar.com

- José Antonio Tolosa, "THE ALJAFERÍA (ZARAGOZA). Palacio mudéjar -Sala de Pedro IV-", aragonmudejar.com

- José Antonio Tolosa, "THE ALJAFERÍA (ZARAGOZA). Saint George's Chapel", aragonmudejar.com

- José Antonio Tolosa, "Introducción al Palacio de los Reyes Católicos", aragonmudejar.com

- José Antonio Tolosa, "Heraldry in the Palace of the Catholic Kings", aragonmudejar.com

- Pedro I. Sobradiel (1998), La Aljafería entra en el siglo veintiuno totalmente renovada tras cinco décadas de restauración, Grafimar·ca, S. L.. Institution "Fernando el Católico", p. 84, ISBN 84-7820-386-9

- Pedro I. Sobradiel (2006), La Aljafería filipina. 1591-1597. Los Años de Hierro (PDF), Arte Islámico. Collection Fuentes Documentales, Zaragoza: Institute of Islamic Studies and the Near East. Mixed Center between the Courts of Aragon. The Higher Council for Scientific Research and the University of Zaragoza, ISBN 84-95736-38-1

Bibliography

- BORRÁS GUALIS, Gonzalo (1991). "La ciudad islámica". Guillermo Fatás (dir.) Guía histórico-artística de Zaragoza. Zaragoza City Council. pp. 71–100. 3rd ed. ISBN 978-84-86807-76-4

- BIEL IBÁÑEZ, María Pilar (2008). "Nuevas noticias sobre el palacio de la Aljafería". Guillermo Fatás (dir.) Guía histórico-artística de Zaragoza. Zaragoza City Council. pp. 711–727. 4th ed. ISBN 978-84-7820-948-4.

- CABAÑERO SUBIZA, Bernabé et al. (1998), La Aljafería. I. Zaragoza: Cortes de Aragón. 1998. ISBN 978-84-86794-97-2

- EXPÓSITO SEBASTIÁN et al. (2006). La Aljafería de Zaragoza. Zaragoza: Cortes de Aragón. 2006 (6ª ed.) ISBN 978-84-86794-13-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Palacio de la Aljafería (Zaragoza). |

- Aljafería Palace in Museum with no frontiers

- Virtual Visit to the Aljafería Palace

- Al-Andalus: the art of Islamic Spain, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Aljafería (see index)