Slavs

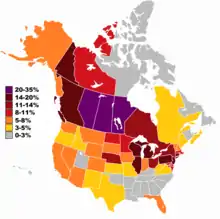

Slavs are ethnolinguistic groups of people who speak the various Slavic languages of the larger Balto-Slavic linguistic group of the Indo-European language family. They are native to Eurasia, stretching from Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe all the way north and eastwards to Northeast Europe, Northern Asia (Siberia) and Central Asia (especially Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan), as well as historically in Western Europe (particularly in Eastern Germany) and Western Asia (including Anatolia). From the early 6th century they spread to inhabit most of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe. Today, there is a large Slavic diaspora throughout North America, particularly in the United States and Canada as a result of immigration.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Slavs are the largest ethno-linguistic group in Europe.[2][3] Present-day Slavic people are classified into East Slavs (chiefly Belarusians, Russians, Rusyns, and Ukrainians), West Slavs (chiefly Czechs, Kashubs, Poles, Slovaks and Sorbs) and South Slavs (chiefly Bosniaks, Bulgarians, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs and Slovenes).[4][5][6][7]

Most Slavs are traditionally Christians. Eastern Orthodox Christianity, first introduced by missionaries from the Byzantine empire, is practiced by the majority of Slavs. The Orthodox Slavs include the Belarusians, Bulgarians, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Russians, Serbs, and Ukrainians and are defined by Orthodox customs and Cyrillic script (Montenegrins and Serbs also use Latin script on equal terms).

The second most common type of Christianity among the Slavs is Catholicism, introduced by Latin-speaking missionaries from Western Europe. The Catholic Slavs include Croats, Czechs, Kashubs, Poles, Silesians, Slovaks, Slovenes and Sorbs and are defined by their Latinate influence and heritage and connection to Western Europe. Millions of Slavs also belong to Greek Catholic churches—that is, historically Orthodox communities that are now in visible unity with Rome and the Catholic Church, but which retain Byzantine practices, such as the Rusyns. There are also substantial Protestant, in particular Lutheran, minorities, especially among the West Slavs, such as the historical Bohemian (Czech) Hussites.

A small number of Slavic ethnic groups traditionally adhere to Islam. Muslim Slavs include the Bosniaks, Pomaks (Bulgarian Muslims), Gorani, Torbeši (Macedonian Muslims) and other Muslims of the former Yugoslavia.

Modern Slavic nations and ethnic groups are considerably diverse both genetically and culturally, and relations between them – even within the individual groups – range from "ethnic solidarity to mutual feelings of hostility".[8]

Ethnonym

The oldest mention of the Slavic ethnonym is the 6th century AD Procopius, writing in Byzantine Greek, using various forms such as Sklaboi (Σκλάβοι), Sklabēnoi (Σκλαβηνοί), Sklauenoi (Σκλαυηνοί), Sthlabenoi (Σθλαβηνοί), or Sklabinoi (Σκλαβῖνοι),[9] while his contemporary Jordanes refers to the Sclaveni in Latin.[10] The oldest documents written in Old Church Slavonic, dating from the 9th century, attest the autonym as Slověne (Словѣне). These forms point back to a Slavic autonym which can be reconstructed in Proto-Slavic as *Slověninъ, plural Slověne.

The reconstructed autonym *Slověninъ is usually considered a derivation from slovo ("letter"), originally denoting "people who speak (the same language)", i. e. people who understand each other, in contrast to the Slavic word denoting German people, namely *němьcь, meaning "silent, mute people" (from Slavic *němъ "mute, mumbling"). The word slovo ("word") and the related slava ("glory, fame") and slukh ("hearing") originate from the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱlew- ("be spoken of, glory"), cognate with Ancient Greek κλέος (kléos "fame"), as in the name Pericles, Latin clueo ("be called"), and English loud.

In Medieval and Early Modern sources written in Latin, Slavs are most commonly referred to as Sclaveni, or in shortened version Sclavi.[11]

Origins

First mentions

Ancient Roman sources refer to the Early Slavic peoples as Veneti, who dwelt in a region of central Europe east of the Germanic tribe of Suebi, and west of the Iranian Sarmatians in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD.[13][14] The Slavs under name of the Antes and the Sclaveni first appear in Byzantine records in the early 6th century. Byzantine historiographers under emperor Justinian I (527–565), such as Procopius of Caesarea, Jordanes and Theophylact Simocatta describe tribes of these names emerging from the area of the Carpathian Mountains, the lower Danube and the Black Sea, invading the Danubian provinces of the Eastern Empire.

Jordanes, in his work Getica (written in 551 AD),[15] describes the Veneti as a "populous nation" whose dwellings begin at the sources of the Vistula and occupy "a great expanse of land". He also describes the Veneti as the ancestors of Antes and Slaveni, two early Slavic tribes, who appeared on the Byzantine frontier in the early 6th century. Procopius wrote in 545 that "the Sclaveni and the Antae actually had a single name in the remote past; for they were both called Sporoi in olden times". The name Sporoi derives from Greek σπείρω ("I scatter grain"). He described them as barbarians, who lived under democracy, believed in one god, "the maker of lightning" (Perun), to whom they made a sacrifice. They lived in scattered housing and constantly changed settlement. In war, they were mainly foot soldiers with small shields and spears, lightly clothed, some entering battle naked with only genitals covered. Their language is "barbarous" (that is, not Greek), and the two tribes are alike in appearance, being tall and robust, "while their bodies and hair are neither very fair or blond, nor indeed do they incline entirely to the dark type, but they are all slightly ruddy in color. And they live a hard life, giving no heed to bodily comforts..."[16] Jordanes described the Sclaveni having swamps and forests for their cities.[17] Another 6th-century source refers to them living among nearly impenetrable forests, rivers, lakes, and marshes.[18]

Menander Protector mentions a Daurentius (circa 577–579) who slew an Avar envoy of Khagan Bayan I for asking the Slavs to accept the suzerainty of the Avars; Daurentius declined and is reported as saying: "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs – so it shall always be for us".[19]

Migrations

According to eastern homeland theory, prior to becoming known to the Roman world, Slavic-speaking tribes were part of the many multi-ethnic confederacies of Eurasia – such as the Sarmatian, Hun and Gothic empires. The Slavs emerged from obscurity when the westward movement of Germanic tribes in the 5th and 6th centuries CE (thought to be in conjunction with the movement of peoples from Siberia and Eastern Europe: Huns, and later Avars and Bulgars) started the great migration of the Slavs, who settled the lands abandoned by Germanic tribes fleeing the Huns and their allies: westward into the country between the Oder and the Elbe-Saale line; southward into Bohemia, Moravia, much of present-day Austria, the Pannonian plain and the Balkans; and northward along the upper Dnieper river. It has also been suggested that some Slavs migrated with the Vandals to the Iberian Peninsula and even North Africa.[20]

Around the 6th century, Slavs appeared on Byzantine borders in great numbers.[21] Byzantine records note that Slav numbers were so great, that grass would not regrow where the Slavs had marched through. After a military movement even the Peloponnese and Asia Minor were reported to have Slavic settlements.[22] This southern movement has traditionally been seen as an invasive expansion.[23] By the end of the 6th century, Slavs had settled the Eastern Alps regions.

Pope Gregory I in 600 wrote to the bishop of Salona Maximus in which he expresses concern about the arrival of Slavs "Et quidem de Sclavorum gente, quae vobis valde imminet, et affligor vehementer et conturbor. Affligor in his quae jam in vobis patior; conturbor, quia per Istriae aditum jam ad Italiam intrare coeperunt" (And as for the people of the Slavs who are really approaching you, I am very depressed and confused. I am depressed because I sympathize with you, confused because they over the Istria began to enter the Italy)[24]

Middle Ages

When Slav migrations ended, their first state organizations appeared, each headed by a prince with a treasury and a military force. In the 7th century, the Frankish merchant Samo supported the Slavs against their Avar rulers and became the ruler of the first known Slav state in Central Europe, Samo's Empire. This early Slavic polity probably did not outlive its founder and ruler, but it was the foundation for later West Slavic states on its territory. The oldest of them was Carantania; others are the Principality of Nitra, the Moravian principality (see under Great Moravia) and the Balaton Principality. The First Bulgarian Empire was founded in 681 as an alliance between the ruling Bulgars and the numerous slavs in the area, and their South Slavic language, the Old Church Slavonic, became the main and official language of the empire in 864. Bulgaria was instrumental in the spread of Slavic literacy and Christianity to the rest of the Slavic world. The expansion of the Magyars into the Carpathian Basin and the Germanization of Austria gradually separated the South Slavs from the West and East Slavs. Later Slavic states, which formed in the following centuries, included the Kievan Rus', the Second Bulgarian Empire, the Kingdom of Poland, Duchy of Bohemia, the Kingdom of Croatia, Banate of Bosnia and the Serbian Empire.

Modern era

In the late 19th century, there were only four Slavic states in the world: the Russian Empire, the Principality of Serbia, the Principality of Montenegro and the Principality of Bulgaria. In the Austro-Hungarian Empire, out of approximately 50 million people, about 23 million were Slavs. The Slavic peoples who were, for the most part, denied a voice in the affairs of Austria-Hungary, called for national self-determination. Because of the vastness and diversity of the territory occupied by Slavic people, there were several centers of Slavic consolidation. At the beginning of the 20th century, following the end of World War I and the collapse of the Central Powers, several Slavic nations re-emerged and became independent, such as the Second Polish Republic, First Czechoslovak Republic, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (officially named Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes until 1929). After the end of the Cold War and subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, additional new Slavic states emerged, such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Belarus, Russia and Ukraine.

Pan-Slavism

Pan-Slavism, a movement which came into prominence in the mid-19th century, emphasized the common heritage and unity of all the Slavic peoples. The main focus was in the Balkans where the South Slavs had been ruled for centuries by other empires: the Byzantine Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice.

Languages

Slovene

Proto-Slavic, the supposed ancestor language of all Slavic languages, is a descendant of common Proto-Indo-European, via a Balto-Slavic stage in which it developed numerous lexical and morphophonological isoglosses with the Baltic languages. In the framework of the Kurgan hypothesis, "the Indo-Europeans who remained after the migrations [from the steppe] became speakers of Balto-Slavic".[25] Proto-Slavic is defined as the last stage of the language preceding the geographical split of the historical Slavic languages. That language was uniform, and on the basis of borrowings from foreign languages and Slavic borrowings into other languages, cannot be said to have any recognizable dialects – this suggests that there was, at one time, a relatively small Proto-Slavic homeland.[26]

Slavic linguistic unity was to some extent visible as late as Old Church Slavonic (or Old Bulgarian) manuscripts which, though based on local Slavic speech of Thessaloniki, could still serve the purpose of the first common Slavic literary language.[27] Slavic studies began as an almost exclusively linguistic and philological enterprise. As early as 1833, Slavic languages were recognized as Indo-European.

Standardised Slavic languages that have official status in at least one country are: Belarusian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Croatian, Czech, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Polish, Russian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, and Ukrainian.

The alphabets used for Slavic languages are frequently connected to the dominant religion among the respective ethnic groups. Orthodox Christians use the Cyrillic alphabet while Catholics use the Latin alphabet; the Bosniaks, who are Muslim, also use the Latin alphabet. Additionally, some Eastern Catholics and Western Catholics use the Cyrillic alphabet. Serbian and Montenegrin use both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets. There is also a Latin script to write in Belarusian, called Łacinka.

Ethno-cultural subdivisions

Slavs are customarily divided along geographical lines into three major subgroups: West Slavs, East Slavs, and South Slavs, each with a different and a diverse background based on the unique history, religion and culture of particular Slavic groups within them. Apart from prehistorical archaeological cultures, the subgroups have had notable cultural contact with non-Slavic Bronze- and Iron Age civilisations. Modern Slavic nations and ethnic groups are considerably diverse both genetically and culturally, and relations between them – even within the individual ethnic groups themselves – are varied, ranging from a sense of connection to mutual feelings of hostility.[8]

West Slavs originate from early Slavic tribes which settled in Central Europe after the East Germanic tribes had left this area during the migration period.[28] They are noted as having mixed with Germanics, Hungarians, Celts (particularly the Boii), Old Prussians, and the Pannonian Avars.[29] The West Slavs came under the influence of the Western Roman Empire (Latin) and of the Catholic Church.

East Slavs have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed and contacted with Finno-Ugric peoples and Balts.[30][31] Their early Slavic component, Antes, mixed or absorbed Iranians, and later received influence from the Khazars and Vikings.[32] The East Slavs trace their national origins to the tribal unions of Kievan Rus' and Rus' Khaganate, beginning in the 10th century. They came particularly under the influence of the Byzantine Empire and of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

South Slavs from most of the region have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed with the local Proto-Balkanic tribes (Illyrian, Dacian, Thracian, Paeonian, Hellenic tribes), and Celtic tribes (particularly the Scordisci), as well as with Romans (and the Romanized remnants of the former groups), and also with remnants of temporarily settled invading East Germanic, Asiatic or Caucasian tribes such as Gepids, Huns, Avars, Goths and Bulgars. The original inhabitants of present-day Slovenia and continental Croatia have origins in early Slavic tribes who mixed with Romans and romanized Celtic and Illyrian people as well as with Avars and Germanic peoples (Lombards and East Goths). The South Slavs (except the Slovenes and Croats) came under the cultural sphere of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire), of the Ottoman Empire and of the Eastern Orthodox Church and Islam, while the Slovenes and the Croats were influenced by the Western Roman Empire (Latin) and thus by the Catholic Church in a similar fashion to that of the West Slavs.

Religion

%22%252C_Krak%C3%B3w_2013.2.jpg.webp)

The pagan Slavic populations were Christianized between the 7th and 12th centuries. Orthodox Christianity is predominant among East and South Slavs, while Catholicism is predominant among West Slavs and some western South Slavs. The religious borders are largely comparable to the East–West Schism which began in the 11th century.

The majority of contemporary Slavic populations who profess a religion are Orthodox, followed by Catholic, while a small minority are Protestant. There are minor Slavic Muslim groups. Religious delineations by nationality can be very sharp; usually in the Slavic ethnic groups, the vast majority of religious people share the same religion. In the Czech Republic 75% had no stated religion according to the 2011 census.

|

Mainly Eastern Orthodoxy:

|

Mainly Catholicism:

|

Mainly Islam:

|

Relations with non-Slavic people

Throughout their history, Slavs came into contact with non-Slavic groups. In the postulated homeland region (present-day Ukraine), they had contacts with the Iranian Sarmatians and the Germanic Goths. After their subsequent spread, the Slavs began assimilating non-Slavic peoples. For example, in the Balkans, there were Paleo-Balkan peoples, such as Romanized and Hellenized (Jireček Line) Illyrians, Thracians and Dacians, as well as Greeks and Celtic Scordisci and Serdi.[36] Because Slavs were so numerous, most indigenous populations of the Balkans were Slavicized. Thracians and Illyrians mixed as ethnic groups in this period. A notable exception is Greece, where Slavs were Hellenized because Greeks were more numerous, especially with more Greeks returning to Greece in the 9th century and the influence of the church and administration,[37] however, Slavicized regions within Macedonia, Thrace and Moesia Inferior also had a larger portion of locals compared to migrating Slavs.[38] Other notable exceptions are the territory of present-day Romania and Hungary, where Slavs settled en route to present-day Greece, North Macedonia, Bulgaria and East Thrace but assimilated, and the modern Albanian nation which claims descent from Illyrians and other Balkan tribes.

Ruling status of Bulgars and their control of land cast the nominal legacy of the Bulgarian country and people onto future generations, but Bulgars were gradually also Slavicized into the present-day South Slavic ethnic group known as Bulgarians. The Romance speakers within the fortified Dalmatian cities retained their culture and language for a long time.[39] Dalmatian Romance was spoken until the high Middle Ages, but, they too were eventually assimilated into the body of Slavs.

In the Western Balkans, South Slavs and Germanic Gepids intermarried with invaders, eventually producing a Slavicized population. In Central Europe, the West Slavs intermixed with Germanic, Hungarian, and Celtic peoples, while in Eastern Europe the East Slavs had encountered Finnic and Scandinavian peoples. Scandinavians (Varangians) and Finnic peoples were involved in the early formation of the Rus' state but were completely Slavicized after a century. Some Finno-Ugric tribes in the north were also absorbed into the expanding Rus population.[40] In the 11th and 12th centuries, constant incursions by nomadic Turkic tribes, such as the Kipchak and the Pecheneg, caused a massive migration of East Slavic populations to the safer, heavily forested regions of the north.[41] In the Middle Ages, groups of Saxon ore miners settled in medieval Bosnia, Serbia and Bulgaria, where they were Slavicized.

Saqaliba refers to the Slavic mercenaries and slaves in the medieval Arab world in North Africa, Sicily and Al-Andalus. Saqaliba served as caliph's guards.[42][43] In the 12th century, Slavic piracy in the Baltics increased. The Wendish Crusade was started against the Polabian Slavs in 1147, as a part of the Northern Crusades. The pagan chief of the Slavic Obodrite tribes, Niklot, began his open resistance when Lothar III, Holy Roman Emperor, invaded Slavic lands. In August 1160 Niklot was killed, and German colonization (Ostsiedlung) of the Elbe-Oder region began. In Hanoverian Wendland, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lusatia, invaders started germanization. Early forms of germanization were described by German monks: Helmold in the manuscript Chronicon Slavorum and Adam of Bremen in Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum.[44] The Polabian language survived until the beginning of the 19th century in what is now the German state of Lower Saxony.[45] In Eastern Germany, around 20% of Germans have historic Slavic paternal ancestry, as revealed in Y-DNA testing.[46] Similarly, in Germany, around 20% of the foreign surnames are of Slavic origin.[47]

Cossacks, although Slavic-speaking and practicing Orthodox Christianity, came from a mix of ethnic backgrounds, including Tatars and other Turks. Initially, the Cossacks were a mini-subethnos, but now they are less than 5%, and most of them live in the east of Ukraine.[48] Many early members of the Terek Cossacks were Ossetians. The Gorals of southern Poland and northern Slovakia are partially descended from Romance-speaking Vlachs, who migrated into the region from the 14th to 17th centuries and were absorbed into the local population. The population of Moravian Wallachia also descended from the Vlachs. Conversely, some Slavs were assimilated into other populations. Although the majority continued towards Southeast Europe, attracted by the riches of the area that became the state of Bulgaria, a few remained in the Carpathian Basin in Central Europe and were assimilated into the Magyar people. Numerous river and other place names in Romania have Slavic origin.[49]

Population

There is an estimated ca. 350 million Slavs worldwide.

See also

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Gord (archaeology)

- Lech, Čech, and Rus

- List of modern ethnic groups

- List of Slavic tribes

- Panethnicity

- Pan-Slavic colors

- Slavic names

- Bulgarisation

- Russification

- Serbianisation

- Polonization

References

Citations

- "Geography and ethnic geography of the Balkans to 1500". 25 February 1999. Archived from the original on 25 February 1999.

- "Slavic Countries". WorldAtlas.

- Barford 2001, p. 1.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (18 September 2006). "Slav (people) – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 18 August 2010.

- Kamusella, Tomasz; Nomachi, Motoki; Gibson, Catherine (2016). The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137348395.

- Serafin, Mikołaj (January 2015). "Cultural Proximity of the Slavic Nations" (PDF). Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Živković, Tibor; Crnčević, Dejan; Bulić, Dejan; Petrović, Vladeta; Cvijanović, Irena; Radovanović, Bojana (2013). The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Belgrade: Istorijski institut. ISBN 978-8677431044.

- Robert Bideleux; Ian Jeffries (January 1998). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-16112-1.

- Procopius, History of the Wars,\, VII. 14. 22–30, VIII.40.5

- Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, V.33.

- Curta 2001, p. 41-42, 50, 55, 60, 69, 75, 88.

- Balabanov, Kosta (2011). Vinica Fortress : mythology, religion and history written with clay. Skopje: Matica. pp. 273–309.

- Coon, Carleton S. (1939) The Peoples of Europe. Chapter VI, Sec. 7 New York: Macmillan Publishers.

- Tacitus. Germania, page 46.

- Curta 2001: 38. Dzino 2010: 95.

- "Procopius, History of the Wars, VII. 14. 22–30". Clas.ufl.edu. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Jordanes, The Origin and Deeds of the Goths, V. 35.

- Maurice's Strategikon: handbook of Byzantine military strategy, trans. G.T. Dennis (1984), p. 120.

- Curta 2001, pp. 91–92, 315.

- Mallory & Adams "Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture

- Cyril A. Mango (1980). Byzantium, the empire of New Rome. Scribner. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-684-16768-8.

- Tachiaos, Anthony-Emil N. 2001. Cyril and Methodius of Thessalonica: The Acculturation of the Slavs. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press.

- Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou 1992: Middle Ages

- Željko Rapanić; (2013) O početcima i nastajanju Dubrovnika (The origin and formation of Dubrovnik. additional considerations) p. 94; Starohrvatska prosvjeta, Vol. III No. 40,

- F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies, vol. 18 (1990), pp. 131–140. Online version, p.4.

- F. Kortlandt, The spread of the Indo-Europeans, Journal of Indo-European Studies, vol. 18 (1990), pp. 131–140. Online version, p.3.

- J.P. Mallory and D.Q. Adams, The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World (2006), pp. 25–26.

- Kobyliński, Zbigniew (1995). "The Slavs". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 1, c.500-c.700. Cambridge University Press. p. 531. ISBN 9780521362917.

- Roman Smal Stocki (1950). Slavs and Teutons: The Oldest Germanic-Slavic Relations. Bruce.

- Raymond E. Zickel; Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1 December 1991). Soviet Union: A Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-8444-0727-2.

- Comparative Politics. Pearson Education India. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-81-317-6033-8.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 237.

- "Релігійні вподобання населення України | Infolight". infolight.org.ua.

- "FIELD LISTING :: RELIGIONS". CIA.

- GUS, Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludnosci 2011: 4.4. Przynależność wyznaniowa (National Survey 2011: 4.4 Membership in faith communities) p. 99/337 (PDF file, direct download 3.3 MB). ISBN 978-83-7027-521-1 Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3, Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries BC by John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, and N. G. L. Hammond, ISBN 0521227178, 1992, page 600: „In the place of the vanished Treres and Tilataei we find the Serdi for whom there is no evidence before the first century BC. It has for long being supposed on convincing linguistic and archeological grounds that this tribe was of Celtic origin.“

- Fine 1991, p. 41.

- Florin Curta's An ironic smile: the Carpathian Mountains and the migration of the Slavs, Studia mediaevalia Europaea et orientalia. Miscellanea in honorem professoris emeriti Victor Spinei oblata, edited by George Bilavschi and Dan Aparaschivei, 47–72. Bucharest: Editura Academiei Române, 2018.

- Fine 1991, p. 35.

- Balanovsky, O; Rootsi, S; Pshenichnov, A; Kivisild, T; Churnosov, M; Evseeva, I; Pocheshkhova, E; Boldyreva, M; et al. (2008). "Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 236–250. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.09.019. PMC 2253976. PMID 18179905.

- Klyuchevsky, Vasily (1987). "1: Mysl". The course of the Russian history (in Russian). ISBN 5-244-00072-1. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- Lewis (1994). "ch 1". Archived from the original on 1 April 2001.

- Eigeland, Tor. 1976. "The golden caliphate". Saudi Aramco World, September/October 1976, pp. 12–16.

- "Wend". Britannica.com. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Polabian language". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- "Contemporary paternal genetic landscape of Polish and German populations: from early medieval Slavic expansion to post-World War II resettlements". European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (4): 415–22. 2013. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.190. PMC 3598329. PMID 22968131.

- "Y-chromosomal STR haplotype analysis reveals surname-associated strata in the East-German population". European Journal of Human Genetics. 14 (5): 577–582. 2006. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201572. PMID 16435000.

- The number of Cossacks according to the 2010 census.

- Alexandru Xenopol, Istoria românilor din Dacia Traiană, 1888, vol. I, p. 540

- Анатольев, Сергей (29 September 2003). "Нас 150 миллионов Немного. А могло быть меньше". russkie.org. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- Estimates range between 129 and 134 million. 111 million in the Russian Federation (2010 census), about 16 million ethnic Russians in post-Soviet states (8 M in Ukraine, 4.5 M in Kazakhstan, 1 M in Belarus, 0.6 M Latvia, 0.6 M in Uzbekistan, 0.6 M in Kyrgyzstan. Up to 10 million Russian diaspora elsewhere (mostly Americas and Western Europe).

- "Нас 150 миллионов -Русское зарубежье, российские соотечественники, русские за границей, русские за рубежом, соотечественники, русскоязычное население, русские общины, диаспора, эмиграция". Russkie.org. 20 February 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2013.

- "Чеченцы требуют снести памятник Юрию Буданову - Новости @ inform - РООИВС "Русичи"". 23 June 2012. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012.

- 37.5–38 million in Poland and 21–22 million ethnic Poles or people of ethnic Polish extraction elsewhere. "Polmap. Rozmieszczenie ludności pochodzenia polskiego (w mln)" Archived 15 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- including 36,522,000 single ethnic identity, 871,000 multiple ethnic identity (especially 431,000 Polish and Silesian, 216,000 Polish and Kashubian and 224,000 Polish and another identity) in Poland (according to the census 2011) and estimated over 20,000,000 Polish Diaspora Świat Polonii, witryna Stowarzyszenia Wspólnota Polska: "Polacy za granicą" Archived 8 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine (Polish people abroad as per summary by Świat Polonii, internet portal of the association Wspólnota Polska)

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (January 2013). Ludność. Stan i struktura demograficzno-społeczna [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Główny Urząd Statystyczny. pp. 89–101. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Struktura narodowo-etniczna, językowa i wyznaniowa ludności Polski [Narodowy Spis Powszechny Ludności i Mieszkań 2011] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Główny Urząd Statystyczny. November 2015. pp. 129–136. ISBN 978-83-7027-597-6.

- Paul R. Magocsi (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. University of Toronto Press. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-4426-1021-7.

- "People groups: Ukrainian". Joshua Project. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Vic Satzewich (2003). The Ukrainian Diaspora. Routledge. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-134-43495-4.

- "Svaki drugi Srbin živi izvan Srbije" (PDF). Novosti. May 2014. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- "Serbs around the World by region" (PDF). Serbian Unity Congress. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - web.archive.org

- "Tab. 6.2 Obyvatelstvo podle národnosti podle krajů" [Table. 6.2 Population by nationality, by region] (PDF). Czech Statistical Office (in Czech). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012.

- "Tab. 6.2 Obyvatelstvo podle národnosti podle krajů: výsledky podle trvalého bydliště" [Tab. 6.2 Population by nationality by regions: results for permanent residence] (PDF). Czech Statistical Office (CZSO) (in Czech). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013.

- "Czech Republic". CIA - The World Factbook. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Karatnycky, Adrian (2001). Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties, 2000–2001. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7658-0884-4. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- "Changes in the populations of the majority ethnic groups". belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- "Demographic situation in 2015". Belarus Statistical Office. 27 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- Kolev, Yordan, Българите извън България 1878 – 1945, 2005, р. 18 Quote:"В началото на XXI в. общият брой на етническите българи в България и зад граница се изчислява на около 10 милиона души/In 2005 the number of Bulgarians is 10 million people

- The Report: Bulgaria 2008. Oxford Business Group. 2008. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-902339-92-4. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Danver, Steven L. (10 March 2015). Native Peoples of the World. google.bg. ISBN 9781317464006.

- Cole, Jeffrey E. (25 May 2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. google.bg. ISBN 9781598843033.

- Conference, Foundation for Endangered Languages; Argenter, Joan A.; McKenna Brown, R. (2004). On the Margins of Nations. google.bg. ISBN 9780953824861.

- Daphne Winland (2004), "Croatian Diaspora", in Melvin Ember; Carol R. Ember; Ian Skoggard (eds.), Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures Around the World. Volume I: Overviews and Topics; Volume II: Diaspora Communities, 2 (illustrated ed.), Springer Science+Business, p. 76, ISBN 978-0-306-48321-9,

It is estimated that 4.5 million Croatians live outside Croatia ...

- "Hrvatski Svjetski Kongres". Archived from the original on 23 June 2003. Retrieved 1 June 2016., Croatian World Congress, "4.5 million Croats and people of Croatian heritage live outside of the Republic of Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina"

- Palermo, Francesco (2011). "National Minorities in Inter-State Relations: Filling the Legal Vacuum?". In Francesco Palermo (ed.). National Minorities in Inter-State Relations. Natalie Sabanadze. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 978-90-04-17598-3.

- including 4,353,000 in Slovakia (according to the census 2011), 147,000 single ethnic identity, 19,000 multiple ethnic identity (especially 18,000 Czech and Slovak and 1,000 Slovak and another identity) in Czech Republic (according to the census 2011), 53,000 in Serbia (according to the census 2011), 762,000 in the USA (according to the census 2010 Archived 12 February 2020 at Archive.today), 2,000 single ethnic identity and 1,000 multiple ethnic identity Slovak and Polish in Poland (according to the census 2011), 21,000 single ethnic identity, 43,000 multiple ethnic identity in Canada (according to the census 2006)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Zupančič, Jernej (August 2004). "Ethnic Structure of Slovenia and Slovenes in Neighbouring Countries" (PDF). Slovenia: a geographical overview. Association of the Geographic Societies of Slovenia. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- Nasevski, Boško; Angelova, Dora; Gerovska, Dragica (1995). Матица на Иселениците на Македонија [Matrix of Expatriates of Macedonia] (in Macedonian). Skopje: Macedonian Expatriation Almanac '95. pp. 52–53.

- http://www.stat.gov.mk/Publikacii/knigaX.pdf

- "Volkszählung vom 27. Mai 1970" Germany (West). Statistisches Bundesamt. Kohlhammer Verlag, 1972, OCLC Number: 760396

- "The Institute for European Studies, Ethnological institute of UW" (PDF). Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013. p. 3. Retrieved 2013-03-06.

- Tab. 614a Obyvatelstvo podle věku, národnosti a pohlaví - Český statistický úřad

- "Bilancia podľa národnosti a pohlavia - SR-oblasť-kraj-okres, m-v [om7002rr]" (in Slovak). Statistics of Slovakia. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- including 521,800 single ethnic identity, 99,000 multiple ethnic identity Czech and Moravian, 4,600 multiple ethnic identity Moravian and Silesian, 1,700 multiple ethnic identity Moravian and Slovak in the Czech Republic (according to the census 2011) and 3,300 in Slovakia (according to the census 2011)

- 23,000 in Serbia (according to the census 2011), 327,000 in the USA (according to the census 2010 Archived 12 February 2020 at Archive.today), 21,000 single ethnic identity and 44,000 multiple ethnic identity in Canada (according to the census 2006)

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1995). "The Rusyn Question". Political Thought. http://www.litopys.org.ua/rizne/magocie.htm. 2–3 (6): 221–231.

- including 6,000 single ethnic identity, 4,000 multiple ethnic identity Lemko-Polish, 1,000 multiple ethnic identity Lemko and another in Poland (according to the census 2011).

- Jacques Bacid, PhD. Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University, 1983.

- L. M. Danforth, The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995, Princeton University Press

- "UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile". Lmp.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 9 February 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile". Lmp.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "National Conflict in a Transnational World: Greeks and Macedonians at the CSCE". Gate.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 1-85065-238-4.

- Shea, John (15 November 1994). Macedonia and Greece: The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation - John Shea - Google Books. ISBN 9780786402281. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- "Greece". State.gov. 4 March 2002. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- 304,000 in the USA (according to the census 2010 Archived 12 February 2020 at Archive.today), 6,000 single ethnic identity and 31,000 multiple ethnic identity in Canada (according to the census 2006)

- Montenegrin Census' from 1909 to 2003 — Aleksandar Rakovic<

- Radio i Televizija Crne Gore

- including 16,000 single ethnic identity, 216,000 multiple ethnic identity Polish and Kashubian, 1,000 multiple ethnic identity Kashubian and another in Poland (according to the census 2011).

- [The Kashubs Today: Culture-Language-Identity" http://instytutkaszubski.republika.pl/pdfy/angielski.pdf]

- ["Polen-Analysen. Die Kaschuben" (PDF). Länder-Analysen (in German). Polen NR. 95: 10–13. September 2011. http://www.laender-analysen.de/polen/pdf/PolenAnalysen95.pdf]

- 137,000 in the USA (according to the census 2010 Archived 12 February 2020 at Archive.today), in Canada (according to the census 2006) and 2,000 single ethnic identity and 4,000 multiple ethnic identity in Canada (according to the census 2006)

- Đečević, Vuković-Ćalasan & Knežević 2017, p. 137-157.

- "Popis 2013 BiH". www.popis.gov.ba. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Bloomberg Germany's Sorb Minority Fights to Save Villages From Vattenfall, 18 December 2007

- "Progam političke stranke GIG".

Do Nato intervencije na Srbiju, 24.03.1999.godine, u Gori je živelo oko 18.000 Goranaca. U Srbiji i bivšim jugoslovenskim republikama nalazi se oko 40.000 Goranaca, a značajan broj Goranaca živi i radi u zemljama Evropske unije i u drugim zemljama. Po našim procenama ukupan broj Goranaca, u Gori u Srbiji i u rasejanju iznosi oko 60.000.

- "Национална припадност, Попис 2011". stat.gov.rs. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији (PDF) (in Serbian). Retrieved 22 April 2017.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472061860.

- Secondary sources

- Allentoft, ME (11 June 2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. Nature Research. 522 (7555): 167–172. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..167A. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507. S2CID 4399103.

- Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801439773.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.

- Curta Florin, The early Slavs in Bohemia and Moravia: a response to my critics

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472081493.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0472082605.

- Lacey, Robert. 2003. Great Tales from English History. Little, Brown and Company. New York. 2004. ISBN 0-316-10910-X.

- Lewis, Bernard. Race and Slavery in the Middle East. Oxford Univ. Press.

- Mathieson, Iain (21 February 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. Nature Research. 555 (7695): 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou, Maria. 1992. The "Macedonian Question": A Historical Review. © Association Internationale d'Etudes du Sud-Est Europeen (AIESEE, International Association of Southeast European Studies), Comité Grec. Corfu: Ionian University. (English translation of a 1988 work written in Greek.)

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500–1453. London: Cardinal. ISBN 9780351176449.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Rębała, Krzysztof, et al.. 2007. Y-STR variation among Slavs: evidence for the Slavic homeland in the middle Dnieper basin. Journal of Human Genetics, May 2007, 52(5): 408–414.

- Vlasto, Alexis P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521074599.

Further reading

- "Linguistic Marginalia on Slavic Ethnogensis" (PDF). Sorin Palgia, University of Bucharest.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slavs. |

| Look up Slav in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeny in Eastern and Western Slavs, B. Malyarchuk, T. Grzybowski, M. Derenko, M. Perkova, T. Vanecek, J. Lazur, P. Gomolcaknd I. Tsybovsky, Oxford Journals

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Slavs". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- "Slavs". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- Leopold Lénard (1913). "The Slavs". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.