Doswelliidae

Doswelliidae is an extinct family of carnivorous archosauriform reptiles that lived in North America and Europe during the Middle to Late Triassic period.[1] Long represented solely by the heavily-armored reptile Doswellia, the family's composition has expanded since 2011, although two supposed South American doswelliids (Archeopelta and Tarjadia) were later redescribed as erpetosuchids. Doswelliids were not true archosaurs, but they were close relatives and some studies have considered them among the most derived non-archosaurian archosauriforms.[2] They may have also been related to the Proterochampsidae, a South American family of crocodile-like archosauriforms.[3]

| Doswelliidae | |

|---|---|

| |

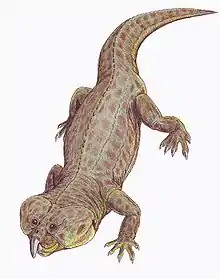

| Life restoration Doswellia kaltenbachi, the most well known dosweliid | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Proterochampsia |

| Family: | †Doswelliidae Weems, 1980 |

| Genera | |

Description

Doswelliids are believed to be semiaquatic carnivores similar to crocodilians in appearance, as evidenced by their short legs and eyes and nostrils which are set high on the head, though the putative member Scleromochlus has been interpreted as a frog-like hopper by one study.[4] They had long bodies and tails, and their front legs were shorter than their hind legs. Unlike in some other groups of archosauriforms, doswelliids retain teeth on the pterygoid, on the roof of the mouth. Although Vancleavea had a short and deep skull, most doswelliids had slender and elongated snouts, similar to other members of Proterochampsia. Advanced doswelliids possessed dorsal ribs which splay outwards (rather than downwards), making their bodies wide and low.[5]

Doswelliids were armored with multiple rows of bony scutes (osteoderms) on their backs. With the exception of Vancleavea, which had many different forms of smooth osteoderms, doswelliid osteoderms were characteristically covered by deep, circular pits. There is also a smooth area (an anterior articular lamina) on the front edge of each osteoderm where the preceding osteoderm overlaps. This combination of osteoderm features is also present in erpetosuchids and some aetosaurs, although the osteoderms of the latter group differ in the arrangement of the pits and the fact that the anterior articular lamina is formed by a raised bar.[3] Doswellia had at least ten rows of osteoderms, creating a flattened carapace-like armor plate on its back. Jaxtasuchus had lighter armor, with only four rows.[5]

Classification

The family was originally named by R. E. Weems in 1980 and was placed in its own suborder, Doswelliina. The Doswelliidae has long been considered a monospecific family of basal archosauriforms represented by Doswellia kaltenbachi from the Late Triassic of North America.[6]

However, a 2011 cladistic analysis by Desojo, Ezcurra, & Schultz recovered the newly named Brazilian genus Archeopelta as well as the enigmatic Argentinian archosauriform Tarjadia as close relatives of Doswellia, within a monophyletic Doswelliidae. These authors defined the family as the most inclusive clade containing all archosauromorphs more closely related to Doswellia kaltenbachi than to Proterochampsa barrionuevoi, Erythrosuchus africanus, Caiman latirostris, (the broad-snouted caiman) or Passer domesticus (the house sparrow).[2]

Within the next few years, several other genera of archosauriforms were classified as Dosweliids. A second New Mexican species of Doswellia was described in 2012;[7] however, this species was subsequently transferred to the separate doswelliid genus Rugarhynchos.[8] Two additional dosweliids were named in 2013: Jaxtasuchus salomoni based on several skeletons found in the Ladinian-age Lower Keuper of Germany,[5] and Ankylosuchus chinlegroupensis based on fragments of four vertebrae, parts of the skull and of a limb bone from the early Carnian Colorado City Formation.[9]

Desojo, Ezcurra, & Schultz (2011)'s analysis placed Doswellidae as the closest large monophyletic clade to Archosauria, with only the Chinese archosauriform Yonghesuchus nested closer to archosaurs.[2] However, a phylogenetic analysis by Ezcurra (2016) recovered Doswelliidae alongside the family Proterochampsidae within the clade Proterochampsia, which was found to be the sister taxon of Archosauria. The unusual aquatic archosauriform Vancleavea was also referred to Doswelliidae in this analysis.[3] Subsequently, Ezcurra et al. (2017) excluded Archeopelta and Tarjadia from Doswelliidae, considering them to be archosaurs of the family Erpetosuchidae instead.[10] Litorosuchus, an aquatic archosauriform which is considered a close relative of Vancleavea, may also be a doswelliid if Vancleavea is a member of the family.

The following cladogram is after Ezcurra (2016):[3]

| Eucrocopoda |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Sues, Hans-Dieter; Desojo, Julia B.; Ezcurra, Martín D. (2013-01-01). "Doswelliidae: a clade of unusual armoured archosauriforms from the Middle and Late Triassic". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 379 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1144/SP379.13. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Julia B. Desojo; Martin D. Ezcurra; Cesar L. Schultz (2011). "An unusual new archosauriform from the Middle–Late Triassic of southern Brazil and the monophyly of Doswelliidae". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (4): 839–871. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2010.00655.x.

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- Bennett, S.C. (2020). "Reassessment of the Triassic archosauriform Scleromochlus taylori: neither runner nor biped, but hopper". PeerJ. 8: e8418. doi:10.7717/peerj.8418. ISSN 2167-8359.

- Schoch, R. R.; Sues, H. D. (2013). "A new archosauriform reptile from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) of Germany". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 12: 113–131. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.781066.

- R. E. Weems (1980). "An unusual newly discovered archosaur from the Upper Triassic of Virginia, U.S.A." Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. New Series. 70 (7): 1–53. doi:10.2307/1006472. JSTOR 1006472.

- Heckert, Andrew B.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A. (2012). "A new species of the enigmatic archosauromorph Doswellia from the Upper Triassic Bluewater Creek Formation, New Mexico, USA". Palaeontology. 55 (6): 1333–1348. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01200.x.

- Brenen M. Wynd; Sterling J. Nesbitt; Michelle R. Stocker; Andrew B. Heckert (2020). "A detailed description of Rugarhynchos sixmilensis, gen. et comb. nov. (Archosauriformes, Proterochampsia), and cranial convergence in snout elongation across stem and crown archosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. in press: e1748042. doi:10.1080/02724634.2019.1748042.

- Lucas, S.G.; Spielmann, J.A.; Hunt, A.P. (2013). "A new doswelliid archosauromorph from the Upper Triassic of West Texas" (PDF). In Tanner, L.H.; Spielmann, J.A.; Lucas, S.G. (eds.). The Triassic System. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 61. pp. 382–388.

- Martín D. Ezcurra; Lucas E. Fiorelli; Agustín G. Martinelli; Sebastián Rocher; M. Belén von Baczko; Miguel Ezpeleta; Jeremías R. A. Taborda; E. Martín Hechenleitner; M. Jimena Trotteyn; Julia B. Desojo (2017). "Deep faunistic turnovers preceded the rise of dinosaurs in southwestern Pangaea". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 1 (10): 1477–1483. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0305-5. PMID 29185518.

| Wikispecies has information related to Doswelliidae. |