Sauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct, diverse taxon of aquatic reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosauria became extinct at the end of that period. The plesiosaurs would continue to diversify until the end of the Mesozoic. Sauropterygians are united by a radical adaptation of their pectoral girdle, adapted to support powerful flipper strokes. Some later sauropterygians, such as the pliosaurs, developed a similar mechanism in their pelvis. Uniquely among reptiles, sauropterygians moved their tail vertically like modern cetaceans and sirenians.[1]

| Sauropterygians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton of Thalassomedon hanningtoni, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Pantestudines (?) |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia Owen, 1860 |

| Subgroups | |

Origins and evolution

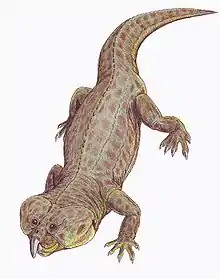

The earliest sauropterygians appeared about 245 million years ago (Ma), at the start of the Triassic period: the first definite sauropterygian with exact stratigraphic datum lies within the Spathian division of the Olenekian era in South China.[2] Early examples were small (around 60 cm), semi-aquatic lizard-like animals with long limbs (pachypleurosaurs), but they quickly grew to be several metres long and spread into shallow waters (nothosaurs). The Triassic-Jurassic extinction event wiped them all out except for the plesiosaurs. During the Early Jurassic, these diversified quickly into both long-necked small-headed plesiosaurs proper, and short-necked large-headed pliosaurs. Originally, it was thought that plesiosaurs and pliosaurs were two distinct superfamilies that followed separate evolutionary paths. It now seems that these were simply morphotypes in that both types evolved a number of times, with some pliosaurs evolving from plesiosaur ancestors, and vice versa.

Classification

Classification of sauropterygians has been difficult. The demands of an aquatic environment caused the same features to evolve multiple times among reptiles, an example of convergent evolution. Sauropterygians are diapsids, and since the late 1990s, scientists have suggested that they may be closely related to turtles. The bulky-bodied, mollusc-eating placodonts may also be sauropterygians, or intermediate between the classic eosauropterygians and turtles. Several analyses of sauropterygian relationships since the beginning of the 2010s have suggested that they are more closely related to archosaurs (birds and crocodilians) than to lepidosaurs (lizards and snakes).[3]

The cladogram shown hereafter is the result of an analysis of sauropterygian relationships (using just fossil evidence) conducted by Neenan and colleagues, in 2013.[4]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Size and ecology

Each morphotype filled a specific ecological role. The large pliosaurs, such as the Jurassic Rhomaleosaurus, Liopleurodon and Pliosaurus, and the Cretaceous Kronosaurus and Brachauchenius, were the superpredators of the Mesozoic seas, around 7 to 12 meters in length, and filled a similar ecological role to that of killer whales today. The long-necked plesiosaurs, meanwhile, included both those with medium-long necks, such as the 3 to 5 metre-long Plesiosauridae and Cryptoclididae, and the Jurassic and Cretaceous Elasmosauridae, which evolved progressively longer and more flexible necks, so that by the middle and late Cretaceous the entire animal was over 13 metres in length (e.g. Elasmosaurus) - although, as most of this was the neck, the actual body size was much smaller than that of the larger pliosaurs. These long-necked forms undoubtedly fed on fish, which they probably snared in their tooth-lined jaws with rapid lunges of the neck and head.

References

- Sennikov, A. G. (2019). "Peculiarities of the Structure and Locomotor Function of the Tail in Sauropterygia". Biology Bulletin. 46 (7): 751–762. doi:10.1134/S1062359019070100. S2CID 211217453.

- Ji Cheng, et al. 2013. "Highly diversified Chaohu fauna (Olenekian, Early Triassic) and sequence of Triassic marine reptile faunas from South China", in Reitner, Joachim et al., eds. Palaeobiology and Geobiology of Fossil Lagerstätten through Earth History p. 80

- Lee, M. S. Y. (2013). "Turtle origins: Insights from phylogenetic retrofitting and molecular scaffolds". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 26 (12): 2729–2738. doi:10.1111/jeb.12268. PMID 24256520. S2CID 2106400.

- Neenan, J. M.; Klein, N.; Scheyer, T. M. (2013). "European origin of placodont marine reptiles and the evolution of crushing dentition in Placodontia". Nature Communications. 4: 1621. doi:10.1038/ncomms2633. PMID 23535642.

External links

- Unit 220: 100: Lepidosauromorpha. Palaeos. July 15, 2003. Retrieved January 19, 2004.

- A review of the Sauropterygia. Adam Stuart Smith. The Plesiosaur Directory. Retrieved April 17, 2006.

- Paleofile taxalist - lists every species and synonyms. Retrieved February 26, 2006

.png.webp)