Jesairosaurus

Jesairosaurus is an extinct genus of early archosauromorph reptile known from the Illizi Province of Algeria. It is known from a single species, Jesairosaurus lehmani.[1] Although a potential relative of the long-necked tanystropheids, this lightly-built reptile could instead be characterized by its relatively short neck as well as various skull features.[2]

| Jesairosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

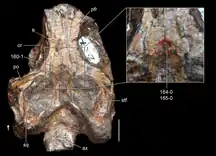

| The holotype (ZAR 06) of Jesairosaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Genus: | †Jesairosaurus Jalil, 1997 |

| Species: | †J. lehmani |

| Binomial name | |

| †Jesairosaurus lehmani Jalil, 1997 | |

Etymology and discovery

Zarzaïtine fossil material has been known since 1957. Much of the material has been recovered by French expeditions in the late 1950s and 1960s, and deposited at the Laboratoire de Paleontologie (Paleontology department) at the Museum national d'Histoire naturalle in Paris. Algerian fossils were prepared at this institution over subsequent years. Several putative procolophonid skeletons reported in 1971 were later determined to belong to "prolacertiforms" in 1990. The term "prolacertiform" is now considered to refer to an unnatural polyphyletic grouping of early archosauromorphs, distant relatives of crocodylians and dinosaurs (including birds). These hematite-encrusted skeletons were finally prepared and described by Nour-Eddine Jalil as the new genus and species Jesairosaurus lehmani in 1997.[1]

The generic name Jesairosaurus means "Al Jesaire lizard" (although Jesairosaurus is not a true lizard), in reference to the Arabic name for Algeria. The specific name honors J.-P. Lehman for describing for the first time vertebrate material from the Triassic of Algeria.[1]

The holotype of Jesairosaurus lehmani is ZAR 06, a partial skeleton including an articulated and three-dimensionally preserved skull, pectoral girdle, cervical (neck) vertebrae, and a partial left humerus (forearm bone). It is also known from nine paratypes including ZAR 07 (a partial skull), ZAR 08 (a partial skull and postcranial skeletons), ZAR 09 (two partial postcranial skeletons), and ZAR 10-15, various postcranial material including vertebrae, pectoral and pelvic girdles, and even a partial hindlimb in ZAR 15. These specimens were collected in the Gour Laoud, locality 5n003 from the base of lower sandstones of the Lower Zarzaïtine Formation of Zarzaïtine Series, dating to the Anisian-Olenekian stages of the Early to the Middle Triassic.[1]

Description

Snout bones and palate

The skull is low, with large orbits (eye holes) and a narrow and relatively short preorbital region (portion in front of the eyes). The precise form of the nares (nostrils) is unknown, but they were probably completely surrounded by the large yet narrow premaxillae (paired tooth-bearing bones of the snout tip) based on the structure of the bones of the snout.[1] The ventral process (lower extension) of each premaxilla was long and possessed a large number of tooth positions. Although only 6 teeth were preserved in the right premaxilla of the holotype, there was room for up to 9 or 10 more teeth.[2]

Each maxilla (a tooth-bearing bone on the side of the snout) has a short anterior and dorsal process (forward and upward extensions in the front part of each maxilla), but a long and boxy posterior (rear) process which forms most of the lower edge of the orbit. The front part of the maxilla is concave and has a hole above the third tooth. An estimated 20 to 21 teeth were present in each maxilla. The front edge of each orbit was formed by a prefrontal bone, and a thin lacrimal was present between each prefrontal and maxilla. The lacrimal likely did not form part of the border of either the orbit or nares.[1][2]

The palatine bones of the roof of the mouth in the front part of the snout extensively contacted the maxillae. Some bones in the front part of the palate (likely the vomers) were also covered in small denticles. Denticles were also present in the back of the palate, likely on the pterygoids and rear parts of the palatine bones. The interpterygoid vacuities (large holes on the side of the palate) were long and thin, while the subtemporal fenestrae (holes in the back of the palate where muscles stretch through) are large.[1]

Postorbital region

The rear lower corners of the orbits are formed by the jugal bones, which extend to the lower part of the skull's postorbital region (behind the eyes). Each jugal had a long and spur-like rear projection which reached as far back as the squamosal bone in the back of the skull. However, this rear projection stretches above each lower temporal fenestra, a hole in the side of the rear part of the skull. This leaves the hole completely open at the bottom, while in many other reptiles the jugal encloses the hole from the bottom.[2]

Just above each jugal lies a triangular postorbital bone. The thin dorsal process of each postorbital forms part of the front edge of each upper temporal fenestra, a large and circular hole at the upper part of the back of the skull. The front edge of each postorbital contacts a moderately large postfrontal bone, which forms part of both the rear edge of the orbit and the front edge of the upper temporal fenestra. Behind the rear tip of each jugal lies a diamond-shaped squamosal bone, which forms the lower edge of the upper temporal fenestra. The concave rear edge of each squamosal articulates with the convex front edge of each quadrate bone, creating a robust and inflexible "peg-and-socket" joint. Each quadrate is robust and points down and back, but there is no evidence that Jesairosaurus possessed quadratojugals (bones which link the jugal and quadrate).[1] In addition, the quadrate lacks a prominently concave rear edge and outwards-projecting front edge, in contrast to the condition in lepidosauromorphs (reptiles closer to lizards than to crocodiles and dinosaurs).[2]

Skull roof and braincase

The frontal bones, which occupy the part of the skull roof between the eyes, are rectangular and form most of the upper edge of the orbits. The parietals, which are situated behind the frontals and between the upper temporal fenestrae, are smaller than the frontals and have lateral (outward) extensions which project downwards to form the rear edge of the upper temporal fenestrae.[1] The front part of the parietals taper inwards above the orbits, and in some specimens (such as ZAR 07), a small pineal foramen can be seen, completely enclosed by that part of the parietals. The pineal foramen is a hole in the middle of the skull which in some modern reptiles houses a sensory organ sometimes referred to as a "third eye".[2]

The supraoccipital bone, the part of the braincase directly above the foramen magnum (the skull's opening for the spinal cord), is large and visible from above, but does not contact the parietals. The paroccipital processes of the opisthotic (inner ear bones on the side of the foramen magnum) are wide enough to reach the squamosals, quadrates, and lateral extensions of the parietals on the sides of the head. The basioccipital bone directly below the foramen magnum has a slight keel along its lower edge. The occipital condyle, an extension of the basioccipital which connects to the vertebrae, is positioned further forward on the skull than the joint between the cranium and the lower jaw.[1][2]

Lower jaw and teeth

The mandibles (lower jaws) are straight and slender, formed by the tooth-bearing dentary bones at the front and the splenial and angular bones at the back. The front tip of the mandibles curves very slightly downwards and inwards. The teeth of Jesairosaurus are pointed and very slightly curved, although they are also conical (particularly so in the maxilla) and only slightly flattened from the side. In addition, the teeth are subthecodont (also known as pleurothecodont). This means that the teeth were positioned in sockets within a long groove edged by walls of bone, with the labial (outer) wall being higher than the lingual (inner) wall.[1][2]

Spine and ribs

Jesairosaurus possessed 9 cervical (neck) vertebrae, and it had an unusually short neck compared to many other basal archosauromorphs, notably the bizarre tanystropheids which it was related to.[2] The neural spines, which jutted out of the top of each vertebrae, were low and narrow, with the exception of the tall neural spine of the axis (second cervical vertebra). In some specimens, all of the neural spines were tilted forwards while in other specimens only the last few had such a condition, with the other vertebrae rising straight up. This is an example of individual variation within the genus. Although poorly preserved, the cervical ribs of Jesairosaurus specimens were long and thin for all cervicals except the axis, in which they were short.[1]

At least 15 dorsal (back) vertebrae were present. The neural spines of these vertebrae were also low and narrow, although they would increase in height towards the back of the body. In some specimens the middle dorsals have additional forward or backward spurs at the base of their neural spines. The centra (main bodies) of the first few dorsal vertebrae are higher than they are broad and also rounded, with each having a concave lower edge. Some also have a shallow depression on the sides. The vertebrae become wider and more robust towards the rear of the body. Mature specimens of this genus lacked a channel for the spinal cord in their vertebrae. Large, plate-like zygapophyses (joints between vertebrae) are also present, along with diapophyses and forward-pointing parapophyses (different types of rib joints at the side and front of each vertebra, respectively). On the other hand, this genus completely lacks intercentra, small bones wedged between the centra of each vertebra in some tetrapod groups. Most of the dorsal ribs are long and project outwards and backwards, except for the last 3 which are short and point slightly forwards. Three rows of long gastralia (belly ribs) are also present.[1][2]

2 sacral (hip) vertebrae were present, possessing tall and thin neural spines. The first few cervical (tail) vertebrae also had tall and thin neural spines, although the majority of the tail is unknown. The caudal ribs are short, point backwards, and are fused to their vertebrae.

Pectoral girdle and forelimbs

Each scapula (shoulder blade) and coracoid (shoulder girdle) is fused into a scapulocoracoid, although they can still be differentiated by a pinched area in the bone. The thin scapula widens into a fan-shaped structure as it extends upwards and backwards. Each coracoid is preserved as a large and broad plate which is expanded towards the rear and pierced by a hole (a coracoid foramen). In head-on view the two sides of the pectoral girdle would have formed an angle of 80 degrees. A rod-like clavicle bone was present along the front edge of each coracoid, and a narrow T-shaped interclavicle was placed between the two coracoids. Possible oval-shaped sternal plates were present behind the pectoral girdle. These plates are bony components of the sternum (breastplate), which in most reptiles is completely cartilaginous and in birds is completely bony.[2]

Each humerus (upper arm bone, the only portion of the forelimbs which is completely preserved) is narrow at the mid-shaft but has expanded proximal (near to the body) and distal (away from the body) ends. The proximal end is the widest part while the distal end has a large notch along its front edge creating a hooked structure. Both the ectepicondylar and entepicondylar foramina (two holes on the distal end of the humerus) are completely closed up. The proximal tips of the radius and ulna (lower arm bones) were also preserved, indicating that they were slender bones.[1]

Pelvis and hindlimbs

Each ilium (upper plate of the pelvis) was very similar to that of Prolacerta and Trilophosaurus. Each ilium was triangular and was bisected by a thick ridge which formed the upper rim of the large acetabulum (hip socket). The lower part of each side of the pelvis was composed of an "puboischiadic plate", formed by the fusion of the forward-projecting pubis and the backwards-projecting ischium. The ischium does not project further back than the rear tip of the ilium. The two puboischiadic plates on either side of the pelvis fuse at the bottom at an 80 degree angle in head-on view.[1]

The femur (thigh bone) was straight and rod-like, with a concave and bony head, although many details are unknown due to the bone being incomplete in all specimens. The tibia and fibula (lower leg bones) were also long, straight, and closely connected. As a whole the hindlimbs seemed to have been longer than the forelimbs, which may have allowed the animal to have been capable of running on two legs for part of the time. The tarsals (ankle bones) are poorly preserved, but the calcaneum (heel bone) seemingly lacked a calcaneal tuber (large bony bump on the side of the bone).[1][2]

Classification

In Jalil's 1997 description, Jesairosaurus was evaluated in a phylogenetic analysis which was conducted in two stages. The first stage analyzed many putative "prolacertiforms" as well as other reptiles, while the second stage omitted four fragmentary taxa: Prolacertoides, Trachelosaurus, Kadimakara, and Malutinisuchus. Both of these analyses recovered Jesairosaurus as a prolacertiform archosauromorph due to features of the skull and neck. Although the first stage of the analysis could not determine specific lineages within Prolacertiformes, the second stage clarified the inner relations of the group. In this second stage, Jesairosaurus was found to be closely related to Malerisaurus due to both of them sharing a thin scapula. In addition, these two were grouped with other advanced prolacertiformes such as the tanystropheids due to having lost their quadratojugal bones.[1]

Jalil's analysis was among the last to find support for the group Prolacertiformes; practically every subsequent analysis starting with Dilkes (1998) found that it was an unnatural grouping of various long-necked archosauromorphs. Since 1998, most analyses placed the majority of prolacertiformes, including Tanystropheus, Macrocnemus, and Protorosaurus, into the group Protorosauria, which resided at the base of Archosauromorpha. Prolacerta, the namesake of Prolacertiformes, was put in a more derived position, closer to archosauriformes (a group of advanced archosauromorphs including animals such as Proterosuchus, Euparkeria, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and other reptiles).[3]

Not only has Prolacertiformes been abandoned by most paleontologists, the validity of Protorosauria has also been called into question. Some paleontologists, such as Martin Ezcurra, have argued that tanystropheids are more closely related to advanced archosauromorphs than they are to Protorosaurus, thus rendering Protorosauria a paraphyletic grade of early archosauromorphs. Ezcurra's 2016 analysis which supported this interpretation also incorporated Jesairosaurus into a variety of large-scale phylogenetic analyses. It was found to be the sister taxon to tanystropheids regardless of whether they were closer to advanced archosauromorphs or to Protorosaurus. Although Jesairosaurus lacked many specific vertebral and pelvic features of tanystropheids, not to mention their long necks, it shared a number of other features with the family.[2]

For example, each premaxilla of Jesairosaurus and tanystropheids had more than five teeth, and the parietal bones of the skull roof stretched forward as far as the orbits. The interclavicle of Jesairosaurus and tanystropheids had a small notch on the front tip, a feature acquired independently of the clade including Prolacerta, Tasmaniosaurus, and Archosauriformes. The lateral branch of the pterygoid bone on the roof of the mouth is also toothless in these reptiles. Finally, they have an expanded entepicondyle (the portion of the distal part of the humerus which faces backwards and inwards).[2]

A phylogenetic analysis performed by De-Oliveira et al. (2020) instead suggests that Jesairosaurus occupies a clade with Dinocephalosaurus at the base of Archosauromorpha, detached from Tanystropheidae entirely.[4]

References

- Nour-Eddine Jalil (1997). "A new prolacertiform diapsid from the Triassic of North Africa and the interrelationships of the Prolacertiformes". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (3): 506–525. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010998. JSTOR 4523832.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Ezcurra, Martín D. (2016-04-28). "The phylogenetic relationships of basal archosauromorphs, with an emphasis on the systematics of proterosuchian archosauriforms". PeerJ. 4: e1778. doi:10.7717/peerj.1778. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4860341. PMID 27162705.

- Dilkes, David W. (1998-04-29). "The early Triassic rhynchosaur Mesosuchus browni and the interrelationships of basal archosauromorph reptiles". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 353 (1368): 501–541. doi:10.1098/rstb.1998.0225. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 1692244.

- De-Oliveira, Tiane M.; Pinheiro, Felipe L.; Da-Rosa, Átila Augusto Stock; Dias-Da-Silva, Sérgio; Kerber, Leonardo (2020-04-08). "A new archosauromorph from South America provides insights on the early diversification of tanystropheids". PLOS ONE. 15 (4): e0230890. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230890. ISSN 1932-6203.