Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II

The Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II is a single-seat, twin turbofan engine, straight wing jet aircraft developed by Fairchild-Republic for the United States Air Force (USAF). It is commonly referred to by the nicknames "Warthog" or "Hog", although the A-10's official name comes from the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, a World War II fighter-bomber effective at attacking ground targets.[4] The A-10 was designed for close air support (CAS) of friendly ground troops, attacking armored vehicles and tanks, and providing quick-action support against enemy ground forces. It entered service in 1976 and is the only production-built aircraft that has served in the USAF that was designed solely for CAS. Its secondary mission is to provide forward air controller-airborne support, by directing other aircraft in attacks on ground targets. Aircraft used primarily in this role are designated OA-10.

| A-10 / OA-10 Thunderbolt II | |

|---|---|

| |

| An A-10 from the 74th Fighter Squadron after taking on fuel over Afghanistan | |

| Role | Close air support attack aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Fairchild Republic |

| First flight | 10 May 1972 |

| Introduction | October 1977[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 1972–1984[2] |

| Number built | 716[3] |

The A-10 was intended to improve on the performance and firepower of the A-1 Skyraider. The A-10 was designed around the 30 mm GAU-8 Avenger rotary cannon. Its airframe was designed for durability, with measures such as 1,200 pounds (540 kg) of titanium armor to protect the cockpit and aircraft systems, enabling it to absorb a significant amount of damage and continue flying. Its short takeoff and landing capability permits operation from airstrips close to the front lines, and its simple design enables maintenance with minimal facilities. The A-10 served in the Gulf War (Operation Desert Storm), the American–led intervention against Iraq's invasion of Kuwait, where the aircraft distinguished itself. The A-10 also participated in other conflicts such as in Grenada, the Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, and against the Islamic State in the Middle East.

The A-10A single-seat variant was the only version produced, though one pre-production airframe was modified into the YA-10B twin-seat prototype to test an all-weather night capable version. In 2005, a program was started to upgrade remaining A-10A aircraft to the A-10C configuration, with modern avionics for use with precision weaponry. The U.S. Air Force had stated the F-35 would replace the A-10 as it entered service, but this remains highly contentious within the USAF and in political circles. With a variety of upgrades and wing replacements, the A-10's service life can be extended to 2040; the service has no planned retirement date as of June 2017.[5]

Development

Background

Post-World War II development of conventionally armed attack aircraft in the United States had stagnated.[6] Design efforts for tactical aircraft focused on the delivery of nuclear weapons using high-speed designs like the F-101 Voodoo and F-105 Thunderchief.[7] Designs concentrating on conventional weapons had been largely ignored, leaving their entry into the Vietnam War led by the Korean War-era Douglas A-1 Skyraider. While a capable aircraft for its era, with a relatively large payload and long loiter time, the propeller-driven design was also relatively slow and vulnerable to ground fire. The U.S. Air Force and Marine Corps lost 266 A-1s in action in Vietnam, largely from small arms fire.[8] The A-1 Skyraider also had poor firepower.[9]

The lack of modern conventional attack capability prompted calls for a specialized attack aircraft.[10][11] On 7 June 1961, Secretary of Defense McNamara ordered the USAF to develop two tactical aircraft, one for the long-range strike and interdictor role, and the other focusing on the fighter-bomber mission. The former became the Tactical Fighter Experimental, or TFX, which emerged as the F-111, while the second was filled by a version of the U.S. Navy's F-4 Phantom II. While the Phantom went on to be one of the most successful fighter designs of the 1960s, and proved to be a capable fighter-bomber, its lack of loiter time was a major problem, and to a lesser extent, its poor low-speed performance. It was also expensive to buy and operate, with a flyaway cost of $2 million in FY1965 ($16.2 million today), and operational costs over $900 per hour ($7,000 per hour today).[12]

After a broad review of its tactical force structure, the U.S. Air Force decided to adopt a low-cost aircraft to supplement the F-4 and F-111. It first focused on the Northrop F-5, which had air-to-air capability.[9] A 1965 cost-effectiveness study shifted the focus from the F-5 to the less expensive LTV A-7D, and a contract was awarded. However, this aircraft doubled in cost with demands for an upgraded engine and new avionics.[9]

Helicopter competition

During this period, the United States Army had been introducing the UH-1 Iroquois into service. First used in its intended role as a transport, it was soon modified in the field to carry more machine guns in what became known as the helicopter gunship role. This proved effective against the lightly armed enemy, and new gun and rocket pods were added. Soon the AH-1 Cobra was introduced. This was an attack helicopter armed with long-range BGM-71 TOW missiles able to destroy tanks from outside the range of defensive fire. The helicopter was effective, and prompted the U.S. military to change its defensive strategy in Europe by blunting any Warsaw Pact advance with anti-tank helicopters instead of the tactical nuclear weapons that had been the basis for NATO's battle plans since the 1950s.[13]

The Cobra was a quickly made helicopter based on the UH-1 Iroquois, and in the late 1960s the U.S. Army was also designing the Lockheed AH-56 Cheyenne, a much more capable attack aircraft with greater speed. These developments worried the USAF, which saw the anti-tank helicopter overtaking its nuclear-armed tactical aircraft as the primary anti-armor force in Europe. A 1966 Air Force study of existing close air support (CAS) capabilities revealed gaps in the escort and fire suppression roles, which the Cheyenne could fill. The study concluded that the service should acquire a simple, inexpensive, dedicated CAS aircraft at least as capable as the A-1, and that it should develop doctrine, tactics, and procedures for such aircraft to accomplish the missions for which the attack helicopters were provided.[14]

A-X program

On 8 September 1966, General John P. McConnell, Chief of Staff of the USAF, ordered that a specialized CAS aircraft be designed, developed, and obtained. On 22 December, a Requirements Action Directive was issued for the A-X CAS airplane,[14] and the Attack Experimental (A-X) program office was formed.[15] On 6 March 1967, the Air Force released a request for information to 21 defense contractors for the A-X. The objective was to create a design study for a low-cost attack aircraft.[11] In 1969, the Secretary of the Air Force asked Pierre Sprey to write the detailed specifications for the proposed A-X project; Sprey's initial involvement was kept secret due to his earlier controversial involvement in the F-X project.[11] Sprey's discussions with Skyraider pilots operating in Vietnam and analysis of aircraft used in the role indicated the ideal aircraft should have long loiter time, low-speed maneuverability, massive cannon firepower, and extreme survivability;[11] possessing the best elements of the Ilyushin Il-2, Henschel Hs 129, and Skyraider. The specifications also demanded that each aircraft cost less than $3 million (equivalent to $20.9 million today).[11] Sprey required that the biography of World War II Luftwaffe attack pilot Hans-Ulrich Rudel be read by people on the A-X program.[16]

In May 1970, the USAF issued a modified, more detailed request for proposals for the aircraft. The threat of Soviet armored forces and all-weather attack operations had become more serious. The requirements now included that the aircraft would be designed specifically for the 30 mm rotary cannon. The RFP also specified a maximum speed of 460 mph (400 kn; 740 km/h), takeoff distance of 4,000 feet (1,200 m), external load of 16,000 pounds (7,300 kg), 285-mile (460 km) mission radius, and a unit cost of US$1.4 million ($9.2 million today).[17] The A-X would be the first USAF aircraft designed exclusively for close air support.[18] During this time, a separate RFP was released for A-X's 30 mm cannon with requirements for a high rate of fire (4,000 round per minute) and a high muzzle velocity.[19] Six companies submitted aircraft proposals, with Northrop and Fairchild Republic selected to build prototypes: the YA-9A and YA-10A, respectively. General Electric and Philco-Ford were selected to build and test GAU-8 cannon prototypes.[20]

Two YA-10 prototypes were built in the Republic factory in Farmingdale, New York, and first flown on 10 May 1972 by pilot Howard "Sam" Nelson. Production A-10s were built by Fairchild in Hagerstown, Maryland. After trials and a fly-off against the YA-9, on 18 January 1973, the USAF announced the YA-10's selection for production.[21] General Electric was selected to build the GAU-8 cannon in June 1973.[22] The YA-10 had an additional fly-off in 1974 against the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7D Corsair II, the principal USAF attack aircraft at the time, to prove the need for a new attack aircraft. The first production A-10 flew in October 1975, and deliveries commenced in March 1976.[23]

One experimental two-seat A-10 Night Adverse Weather (N/AW) version was built by converting an A-10A.[24] The N/AW was developed by Fairchild from the first Demonstration Testing and Evaluation (DT&E) A-10 for consideration by the USAF. It included a second seat for a weapons system officer responsible for electronic countermeasures (ECM), navigation and target acquisition. The N/AW version did not interest the USAF or export customers. The two-seat trainer version was ordered by the Air Force in 1981, but funding was canceled by U.S. Congress and the jet was not produced.[25] The only two-seat A-10 built now resides at Edwards Air Force Base's Flight Test Center Museum.[26]

Production

On 10 February 1976, Deputy Secretary of Defense Bill Clements authorized full-rate production, with the first A-10 being accepted by the Air Force Tactical Air Command on 30 March 1976. Production continued and reached a peak rate of 13 aircraft per month. By 1984, 715 airplanes, including two prototypes and six development aircraft, had been delivered.[2][23]

When A-10 full-rate production was first authorized the aircraft's planned service life was 6,000 hours. A small reinforcement to the design was quickly adopted when the A-10 failed initial fatigue testing at 80% of testing; with the fix, the A-10 passed the fatigue tests. 8,000-flight-hour service lives were becoming common at the time, so fatigue testing of the A-10 continued with a new 8,000-hour target. This new target quickly discovered serious cracks at Wing Station 23 (WS23) where the outboard portions of the wings are joined to the fuselage. The first production change was to add cold working at WS23 to address this problem. Soon after, the Air Force determined that the real-world A-10 fleet fatigue was more harsh than estimated, forcing them to change their fatigue testing and introduce "spectrum 3" equivalent flight-hour testing.[9]

Spectrum 3 fatigue testing started in 1979. This round of testing quickly determined that more drastic reinforcement would be needed. The second change in production, starting with aircraft #442, was to increase the thickness of the lower skin on the outer wing panels. A tech order was issued to retrofit the "thick skin" to the whole fleet, but the tech order was rescinded after roughly 242 planes, leaving about 200 planes with the original "thin skin". Starting with aircraft #530, cold working at WS0 was performed, and this retrofit was performed on earlier aircraft. A fourth, even more drastic change was initiated with aircraft #582, again to address the problems discovered with spectrum 3 testing. This change increased the thickness on the lower skin on the center wing panel, but it required modifications to the lower spar caps to accommodate the thicker skin. The Air Force determined that it was not economically feasible to retrofit earlier planes with this modification.[9]

Upgrades

The A-10 has received many upgrades since entering service. In 1978, the A-10 received the Pave Penny laser receiver pod, which receives reflected laser radiation from laser designators to allow the aircraft to deliver laser guided munitions. The Pave Penny pod is carried on a pylon mounted below the right side of the cockpit and has a clear view of the ground.[27][28] In 1980, the A-10 began receiving an inertial navigation system.[29]

In the early 1990s, the A-10 began to receive the Low-Altitude Safety and Targeting Enhancement (LASTE) upgrade, which provided computerized weapon-aiming equipment, an autopilot, and a ground-collision warning system. In 1999, aircraft began receiving Global Positioning System navigation systems and a multi-function display.[30] The LASTE system was upgraded with an Integrated Flight & Fire Control Computer (IFFCC).[31]

Proposed further upgrades included integrated combat search and rescue locator systems and improved early warning and anti-jam self-protection systems, and the Air Force recognized that the A-10's engine power was sub-optimal and had been planning to replace them with more powerful engines since at least 2001 at an estimated cost of $2 billion.[32]

HOG UP and Wing Replacement Program

In 1987, Grumman Aerospace took over support for the A-10 program. In 1993, Grumman updated the damage tolerance assessment and Force Structural Maintenance Plan and Damage Threat Assessment. Over the next few years, problems with wing structure fatigue, first noticed in production years earlier, began to come to the fore. The process of implementing the maintenance plan was greatly delayed by the base realignment and closure commission (BRAC), which led to 80% of the original workforce being let go.[33]

During inspections in 1995 and 1996, cracks at the WS23 location were found on many aircraft, most of them in line with updated predictions from 1993. However, two of these were classified as "near-critical" size, well beyond predictions. In August 1998, Grumman produced a new plan to address these issues and increase life span to 16,000 hours. This resulted in the "HOG UP" program, which commenced in 1999. Over time, additional aspects were added to HOG UP, including new fuel bladders, changes to the flight control system, and inspections of the engine nacelles. In 2001, the cracks were reclassified as "critical", which meant they were considered repairs and not upgrades, which allowed bypassing normal acquisition channels for more rapid implementation.[34]

An independent review of the HOG UP program at this point concluded that the data on which the wing upgrade relied could no longer be trusted. This independent review was presented in September 2003. Shortly thereafter, fatigue testing on a test wing failed prematurely and also mounting problems with wings failing in-service inspections at an increasing rate became apparent. The Air Force estimated that they would run out of wings by 2011. Of the plans explored, replacing the wings with new ones was the least expensive, with an initial cost of $741 million, and a total cost of $1.72 billion over the life of the program.[9]

In 2005, a business case was developed with three options to extend the life of the fleet. The first two options involved expanding the service life extension program (SLEP) at a cost of $4.6 billion and $3.16 billion, respectively. The third option, worth $1.72 billion, was to build 242 new wings and avoid the cost of expanding the SLEP. In 2006, option 3 was chosen and Boeing won the contract.[35] The base contract is for 117 wings with options for 125 additional wings.[36] In 2013, the Air Force exercised a portion of the option to add 56 wings, putting 173 wings on order with options remaining for 69 additional wings.[37][38] In November 2011, two A-10s flew with the new wings fitted. The new wings improved mission readiness, decreased maintenance costs, and allowed the A-10 to be operated up to 2035 if necessary.[39] The re-winging effort was organized under the Thick-skin Urgent Spares Kitting (TUSK) Program.[37]

In 2014, as part of plans to retire the A-10, the USAF considered halting the wing replacement program to save an additional $500 million;[40][41] however, by May 2015 the re-winging program was too far into the contract to be financially efficient to cancel.[42] Boeing stated in February 2016 that the A-10 fleet with the new TUSK wings could operate to 2040.[37]

A-10C

In 2005, the entire fleet of 356 A-10 and OA-10 aircraft began receiving the Precision Engagement upgrades including an improved fire control system (FCS), electronic countermeasures (ECM), and smart bomb targeting. The aircraft receiving this upgrade were redesignated A-10C.[43] The Government Accounting Office in 2007 estimated the cost of upgrading, refurbishing, and service life extension plans for the A-10 force to total $2.25 billion through 2013.[18][44] In July 2010, the USAF issued Raytheon a contract to integrate a Helmet Mounted Integrated Targeting (HMIT) system into the A-10C.[44][45] The Air Force Material Command's Ogden Air Logistics Center at Hill AFB, Utah completed work on its 100th A-10 precision engagement upgrade in January 2008.[46] The final aircraft was upgraded to A-10C configuration in June 2011.[47] The aircraft also received all-weather combat capability,[31] and a Hand-on-Throttle-and-Stick configuration mixing the F-16's flight stick with the F-15's throttle. Other changes included two multifunction displays, a modern communications suite including a Link-16 radio and SATCOM.[31][48] The LASTE system was replaced with the integrated flight and fire control computer (IFFCC) included in the PE upgrade.[31]

Throughout its life, the platform's software has been upgraded several times, and although these upgrades were due to be stopped as part of plans to retire the A-10 in February 2014, Secretary of the Air Force Deborah Lee James ordered that the latest upgrade, designated Suite 8, continue in response to Congressional pressure. Suite 8 software includes IFF Mode 5, which modernizes the ability to identify the A-10 to friendly units.[49] Additionally, the Pave Penny pods and pylons are being removed as their receive-only capability has been replaced by the AN/AAQ-28(V)4 LITENING AT targeting pods or Sniper XR targeting pod, which both have laser designators and laser rangefinders.[50]

In 2012, Air Combat Command requested the testing of a 600-US-gallon (2,300 l; 500 imp gal) external fuel tank which would extend the A-10's loitering time by 45–60 minutes; flight testing of such a tank had been conducted in 1997, but did not involve combat evaluation. Over 30 flight tests were conducted by the 40th Flight Test Squadron to gather data on the aircraft's handling characteristics and performance across different load configurations. It was reported that the tank slightly reduced stability in the yaw axis, but there was no decrease in aircraft tracking performance.[51]

Design

Overview

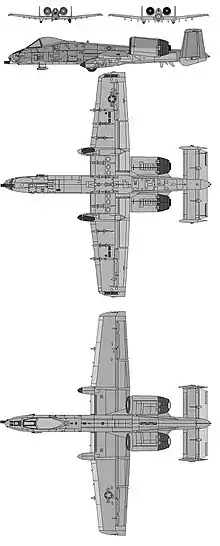

The A-10 has a cantilever low-wing monoplane wing with a wide chord.[32] The aircraft has superior maneuverability at low speeds and altitude because of its large wing area, high wing aspect ratio, and large ailerons. The wing also allows short takeoffs and landings, permitting operations from primitive forward airfields near front lines. The aircraft can loiter for extended periods and operate under 1,000-foot (300 m) ceilings with 1.5-mile (2.4 km) visibility. It typically flies at a relatively low speed of 300 knots (350 mph; 560 km/h), which makes it a better platform for the ground-attack role than fast fighter-bombers, which often have difficulty targeting small, slow-moving targets.[52]

The leading edge of the wing has a honeycomb structure panel construction, providing strength with minimal weight; similar panels cover the flap shrouds, elevators, rudders and sections of the fins.[53] The skin panels are integral with the stringers and are fabricated using computer-controlled machining, reducing production time and cost. Combat experience has shown that this type of panel is more resistant to damage. The skin is not load-bearing, so damaged skin sections can be easily replaced in the field, with makeshift materials if necessary.[54] The ailerons are at the far ends of the wings for greater rolling moment and have two distinguishing features: The ailerons are larger than is typical, almost 50 percent of the wingspan, providing improved control even at slow speeds; the aileron is also split, making it a deceleron.[55][56]

The A-10 is designed to be refueled, rearmed, and serviced with minimal equipment.[57] Its simple design enables maintenance at forward bases with limited facilities.[58][59] An unusual feature is that many of the aircraft's parts are interchangeable between the left and right sides, including the engines, main landing gear, and vertical stabilizers. The sturdy landing gear, low-pressure tires and large, straight wings allow operation from short rough strips even with a heavy aircraft ordnance load, allowing the aircraft to operate from damaged airbases, flying from taxiways, or even straight roadway sections.[60]

The front landing gear is offset to the aircraft's right to allow placement of the 30 mm cannon with its firing barrel along the centerline of the aircraft.[61] During ground taxi, the offset front landing gear causes the A-10 to have dissimilar turning radii. Turning to the right on the ground takes less distance than turning left.[Note 1] The wheels of the main landing gear partially protrude from their nacelles when retracted, making gear-up belly landings easier to control and less damaging. All landing gears retract forward; if hydraulic power is lost, a combination of gravity and aerodynamic drag can lower and lock the gear in place.[56]

Durability

The A-10 is exceptionally tough, being able to survive direct hits from armor-piercing and high-explosive projectiles up to 23 mm. It has double-redundant hydraulic flight systems, and a mechanical system as a back up if hydraulics are lost. Flight without hydraulic power uses the manual reversion control system; pitch and yaw control engages automatically, roll control is pilot-selected. In manual reversion mode, the A-10 is sufficiently controllable under favorable conditions to return to base, though control forces are greater than normal. The aircraft is designed to be able to fly with one engine, half of the tail, one elevator, and half of a wing missing.[62]

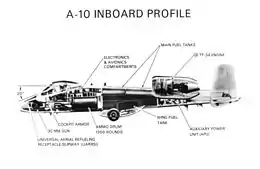

The cockpit and parts of the flight-control systems are protected by 1,200 lb (540 kg) of titanium aircraft armor, referred to as a "bathtub".[63][64] The armor has been tested to withstand strikes from 23 mm cannon fire and some strikes from 57 mm rounds.[59][63] It is made up of titanium plates with thicknesses varying from 0.5 to 1.5 inches (13 to 38 mm) determined by a study of likely trajectories and deflection angles. The armor makes up almost six percent of the aircraft's empty weight. Any interior surface of the tub directly exposed to the pilot is covered by a multi-layer nylon spall shield to protect against shell fragmentation.[65][66] The front windscreen and canopy are resistant to small arms fire.[67]

The A-10's durability was demonstrated on 7 April 2003 when Captain Kim Campbell, while flying over Baghdad during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, suffered extensive flak damage. Iraqi fire damaged one of her engines and crippled the hydraulic system, requiring the aircraft's stabilizer and flight controls to be operated via the 'manual reversion mode.' Despite this damage, Campbell flew the aircraft for nearly an hour and landed safely.[68][69]

The A-10 was intended to fly from forward air bases and semi-prepared runways with high risk of foreign object damage to the engines. The unusual location of the General Electric TF34-GE-100 turbofan engines decreases ingestion risk, and allows the engines to run while the aircraft is serviced and rearmed by ground crews, reducing turn-around time. The wings are also mounted closer to the ground, simplifying servicing and rearming operations. The heavy engines require strong supports: four bolts connect the engine pylons to the airframe.[70] The engines' high 6:1 bypass ratio contributes to a relatively small infrared signature, and their position directs exhaust over the tailplanes further shielding it from detection by infrared homing surface-to-air missiles. The engines' exhaust nozzles are angled nine degrees below horizontal to cancel out the nose-down pitching moment that would otherwise be generated from being mounted above the aircraft's center of gravity and avoid the need to trim the control surfaces to prevent pitching.[70]

To reduce the likelihood of damage to the A-10's fuel system, all four fuel tanks are located near the aircraft's center and are separated from the fuselage; projectiles would need to penetrate the aircraft's skin before reaching a tank's outer skin.[65][66] Compromised fuel transfer lines self-seal; if damage exceeds a tank's self-sealing capabilities, check valves prevent fuel flowing into a compromised tank. Most fuel system components are inside the tanks so that fuel will not be lost due to component failure. The refueling system is also purged after use.[71] Reticulated polyurethane foam lines both the inner and outer sides of the fuel tanks, retaining debris and restricting fuel spillage in the event of damage. The engines are shielded from the rest of the airframe by firewalls and fire extinguishing equipment. In the event of all four main tanks being lost, two self-sealing sump tanks contain fuel for 230 miles (370 km) of flight.[65][66]

Since the A-10 operates extremely close to enemy positions, where it is an easy target for MANPADS, surface-to-air missiles (SAMs), and enemy fighters, it can carry up to 480 flares and 480 chaff cartridges, which is more than any other fighter, but usually flies with a mix of both.[72]

Weapons

Although the A-10 can carry a considerable amount of munitions, its primary built-in weapon is the 30×173 mm GAU-8/A Avenger autocannon. One of the most powerful aircraft cannons ever flown, it fires large depleted uranium armor-piercing shells. The GAU-8 is a hydraulically driven seven-barrel rotary cannon designed specifically for the anti-tank role with a high rate of fire. The cannon's original design could be switched by the pilot to 2,100 or 4,200 rounds per minute;[73] this was later changed to a fixed rate of 3,900 rounds per minute.[74] The cannon takes about half a second to reach top speed, so 50 rounds are fired during the first second, 65 or 70 rounds per second thereafter. The gun is accurate enough to place 80 percent of its shots within a 40-foot (12.4 m) diameter circle from 4,000 feet (1,220 m) while in flight.[75] The GAU-8 is optimized for a slant range of 4,000 feet (1,220 m) with the A-10 in a 30-degree dive.[76]

The fuselage of the aircraft is built around the cannon. The GAU-8/A is mounted slightly to the port side; the barrel in the firing location is on the starboard side at the 9 o'clock position so it is aligned with the aircraft's centerline. The gun's 5-foot, 11.5-inch (1.816 m) ammunition drum can hold up to 1,350 rounds of 30 mm ammunition,[61] but generally holds 1,174 rounds.[76] To protect the GAU-8/A rounds from enemy fire, armor plates of differing thicknesses between the aircraft skin and the drum are designed to detonate incoming shells.[61][66]

The AGM-65 Maverick air-to-surface missile is a commonly used munition for the A-10, targeted via electro-optical (TV-guided) or infrared. The Maverick allows target engagement at much greater ranges than the cannon, and thus less risk from anti-aircraft systems. During Desert Storm, in the absence of dedicated forward-looking infrared (FLIR) cameras for night vision, the Maverick's infrared camera was used for night missions as a "poor man's FLIR".[77] Other weapons include cluster bombs and Hydra rocket pods.[78] The A-10 is equipped to carry GPS and laser-guided bombs, such as the GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb, Paveway series bombs, JDAM, WCMD and glide bomb AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon.[79] A-10s usually fly with an ALQ-131 ECM pod under one wing and two AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles under the other wing for self-defense.[80]

Modernization

The A-10 Precision Engagement Modification Program from 2006 to 2010 updated all A-10 and OA-10 aircraft in the fleet to the A-10C standard with a new flight computer, new glass cockpit displays and controls, two new 5.5-inch (140 mm) color displays with moving map function, and an integrated digital stores management system.[18][43][44][81]

Since then, the A-10 Common Fleet Initiative has led to further improvements: a new wing design, a new data link, the ability to employ smart weapons such as the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) and Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser, as well as the newer GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb, and the ability to carry an integrated targeting pod such as the Northrop Grumman LITENING or the Lockheed Martin Sniper Advanced Targeting Pod (ATP). Also included is the Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) to provide sensor data to personnel on the ground.[43] The A-10C has a Missile Warning System (MWS), which alerts the pilot to whenever there is a missile launch, friendly or non-friendly. The A-10C can also carry a ALQ-184 ECM Pod, which works with the MWS to detect a missile launch, figure out what kind of vehicle is launching the missile or flak (i.e.: SAM, aircraft, flak, MANPAD, etc.) and then jams it with confidential emitting, and selects a countermeasure program that the pilot has pre-set, that when turned on, will automatically dispense flare and chaff at pre-set intervals and amounts.[82]

Colors and markings

Since the A-10 flies low to the ground and at subsonic speed, aircraft camouflage is important to make the aircraft more difficult to see. Many different types of paint schemes have been tried. These have included a "peanut scheme" of sand, yellow and field drab; black and white colors for winter operations and a tan, green and brown mixed pattern.[83] Many A-10s also featured a false canopy painted in dark gray on the underside of the aircraft, just behind the gun. This form of automimicry is an attempt to confuse the enemy as to aircraft attitude and maneuver direction.[84][85] Many A-10s feature nose art, such as shark mouth or warthog head features.

The two most common markings applied to the A-10 have been the European I woodland camouflage scheme and a two-tone gray scheme. The European woodland scheme was designed to minimize visibility from above, as the threat from hostile fighter aircraft was felt to outweigh that from ground-fire. It uses dark green, medium green and dark gray in order to blend in with the typical European forest terrain and was used from the 1980s to the early 1990s. Following the end of the Cold War, and based on experience during the 1991 Gulf War, the air-to-air threat was no longer seen to be as important as that from ground fire, and a new color scheme known as "Compass Ghost" was chosen to minimize visibility from below. This two-tone gray scheme has darker gray color on top, with the lighter gray on the underside of the aircraft, and started to be applied from the early 1990s.[86]

Operational history

Entering service

The first unit to receive the A-10 Thunderbolt II was the 355th Tactical Training Wing, based at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, in March 1976.[87] The first unit to achieve full combat-readiness was the 354th Tactical Fighter Wing at Myrtle Beach Air Force Base, South Carolina, in October 1977.[1] Deployments of A-10As followed at bases both at home and abroad, including England AFB, Louisiana; Eielson AFB, Alaska; Osan Air Base, South Korea; and RAF Bentwaters/RAF Woodbridge, England. The 81st TFW of RAF Bentwaters/RAF Woodbridge operated rotating detachments of A-10s at four bases in Germany known as Forward Operating Locations (FOLs): Leipheim, Sembach Air Base, Nörvenich Air Base, and RAF Ahlhorn.[88]

A-10s were initially an unwelcome addition to many in the Air Force. Most pilots switching to the A-10 did not want to because fighter pilots traditionally favored speed and appearance.[89] In 1987, many A-10s were shifted to the forward air control (FAC) role and redesignated OA-10.[90] In the FAC role, the OA-10 is typically equipped with up to six pods of 2.75 inch (70 mm) Hydra rockets, usually with smoke or white phosphorus warheads used for target marking. OA-10s are physically unchanged and remain fully combat capable despite the redesignation.[91]

A-10s of the 23rd TFW were deployed to Bridgetown, Barbados during Operation Urgent Fury, the American Invasion of Grenada. They provided air cover for the U.S. Marine Corps landings on the island of Carriacou in late October 1983, but did not fire weapons as Marines met no resistance.[92][93][94]

Gulf War and Balkans

The A-10 was used in combat for the first time during the Gulf War in 1991, destroying more than 900 Iraqi tanks, 2,000 other military vehicles and 1,200 artillery pieces.[10] A-10s also shot down two Iraqi helicopters with the GAU-8 cannon. The first of these was shot down by Captain Robert Swain over Kuwait on 6 February 1991 for the A-10's first air-to-air victory.[95][96] Four A-10s were shot down during the war by surface-to-air missiles. Another two battle-damaged A-10s and OA-10As returned to base and were written off. Some sustained additional damage in crash landings.[97][98] The A-10 had a mission capable rate of 95.7 percent, flew 8,100 sorties, and launched 90 percent of the AGM-65 Maverick missiles fired in the conflict.[99] Shortly after the Gulf War, the Air Force abandoned the idea of replacing the A-10 with a close air support version of the F-16.[100]

U.S. Air Force A-10 aircraft fired approximately 10,000 30 mm rounds in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1994–95. Following the seizure of some heavy weapons by Bosnian Serbs from a warehouse in Ilidža, a series of sorties were launched to locate and destroy the captured equipment. On 5 August 1994, two A-10s located and strafed an anti-tank vehicle. Afterward, the Serbs agreed to return remaining heavy weapons.[101] In August 1995, NATO launched an offensive called Operation Deliberate Force. A-10s flew close air support missions, attacking Bosnian Serb artillery and positions. In late September, A-10s began flying patrols again.[102]

A-10s returned to the Balkan region as part of Operation Allied Force in Kosovo beginning in March 1999.[102] In March 1999, A-10s escorted and supported search and rescue helicopters in finding a downed F-117 pilot.[103] The A-10s were deployed to support search and rescue missions, but over time the Warthogs began to receive more ground attack missions. The A-10's first successful attack in Operation Allied Force happened on 6 April 1999; A-10s remained in action until combat ended in late June 1999.[104]

Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and recent deployments

During the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, A-10s did not take part in the initial stages. For the campaign against Taliban and Al Qaeda, A-10 squadrons were deployed to Pakistan and Bagram Air Base, Afghanistan, beginning in March 2002. These A-10s participated in Operation Anaconda. Afterwards, A-10s remained in-country, fighting Taliban and Al Qaeda remnants.[105]

Operation Iraqi Freedom began on 20 March 2003. Sixty OA-10/A-10 aircraft took part in early combat there.[106] United States Air Forces Central Command issued Operation Iraqi Freedom: By the Numbers, a declassified report about the aerial campaign in the conflict on 30 April 2003. During that initial invasion of Iraq, A-10s had a mission capable rate of 85 percent in the war and fired 311,597 rounds of 30 mm ammunition. A single A-10 was shot down near Baghdad International Airport by Iraqi fire late in the campaign. The A-10 also flew 32 missions in which the aircraft dropped propaganda leaflets over Iraq.[107]

In September 2007, the A-10C with the Precision Engagement Upgrade reached initial operating capability.[81] The A-10C first deployed to Iraq in 2007 with the 104th Fighter Squadron of the Maryland Air National Guard.[108] The A-10C's digital avionics and communications systems have greatly reduced the time to acquire a close air support target and attack it.[109]

A-10s flew 32 percent of combat sorties in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. The sorties ranged from 27,800 to 34,500 annually between 2009 and 2012. In the first half of 2013, they flew 11,189 sorties in Afghanistan.[110] From the beginning of 2006 to October 2013, A-10s conducted 19 percent of CAS missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, more than the F-15E Strike Eagle and B-1B Lancer, but less than the 33 percent flown by F-16s.[111]

In March 2011, six A-10s were deployed as part of Operation Odyssey Dawn, the coalition intervention in Libya. They participated in attacks on Libyan ground forces there.[112][113]

The USAF 122nd Fighter Wing revealed it would deploy to the Middle East in October 2014 with 12 of the unit's 21 A-10 aircraft. Although the deployment had been planned a year in advance in a support role, the timing coincided with the ongoing Operation Inherent Resolve against ISIL militants.[114][115][116] From mid-November, U.S. commanders began sending A-10s to hit IS targets in central and northwestern Iraq on an almost daily basis.[117][118] In about two months time, A-10s flew 11 percent of all USAF sorties since the start of operations in August 2014.[119] On 15 November 2015, two days after the ISIL attacks in Paris, A-10s and AC-130s destroyed a convoy of over 100 ISIL-operated oil tanker trucks in Syria. The attacks were part of an intensification of the U.S.-led intervention against ISIL called Operation Tidal Wave II (named after Operation Tidal Wave during World War II, a failed attempt to raid German oil fields) in an attempt to cut off oil smuggling as a source of funding for the group.[120]

On 19 January 2018, 12 A-10s from the 303d Expeditionary Fighter Squadron were deployed to Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan, to provide close-air support, marking the first time in more than three years A-10s had been deployed to Afghanistan.[121]

Future

The future of the platform remains the subject of debate. In 2007, the USAF expected the A-10 to remain in service until 2028 and possibly later,[122] when it would likely be replaced by the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II.[38] However, critics have said that replacing the A-10 with the F-35 would be a "giant leap backwards" given the A-10's performance and the F-35's high costs.[123] In 2012, the Air Force considered the F-35B STOVL variant as a replacement CAS aircraft, but concluded that the aircraft could not generate sufficient sorties.[124] In August 2013, Congress and the Air Force examined various proposals, including the F-35 and the MQ-9 Reaper unmanned aerial vehicle filling the A-10's role. Proponents state that the A-10's armor and cannon are superior to aircraft such as the F-35 for ground attack, that guided munitions other planes rely upon could be jammed, and that ground commanders frequently request A-10 support.[110]

In the USAF's FY 2015 budget, the service considered retiring the A-10 and other single-mission aircraft, prioritizing multi-mission aircraft; cutting a whole fleet and its infrastructure was seen as the only method for major savings. The U.S. Army had expressed interest in obtaining some A-10s should the Air Force retire them,[125][126] but later stated there was "no chance" of that happening.[127] The U.S. Air Force stated that retirement would save $3.7 billion from 2015 to 2019. The prevalence of guided munitions allow more aircraft to perform the CAS mission and reduces the requirement for specialized aircraft; since 2001 multirole aircraft and bombers have performed 80 percent of operational CAS missions. The Air Force also said that the A-10 was more vulnerable to advanced anti-aircraft defenses, but the Army replied that the A-10 had proved invaluable because of its versatile weapons loads, psychological impact, and limited logistics needs on ground support systems.[128]

In January 2015, USAF officials told lawmakers that it would take 15 years to fully develop a new attack aircraft to replace the A-10;[129] that year General Herbert J. Carlisle, the head of Air Combat Command, stated that a follow-on weapon system for the A-10 may need to be developed.[130] It planned for F-16s and F-15Es to initially take up CAS sorties, and later by the F-35A once sufficient numbers become operationally available over the next decade.[131] In July 2015, Boeing held initial discussions on the prospects of selling retired or stored A-10s in near-flyaway condition to international customers.[42] However, the Air Force then said that it would not permit the aircraft to be sold.[132]

Plans to develop a replacement aircraft were announced by the US Air Combat Command in August 2015.[133][134] Early the following year, the Air Force began studying future CAS aircraft to succeed the A-10 in low-intensity "permissive conflicts" like counterterrorism and regional stability operations, admitting that the F-35 would be too expensive to operate in day-to-day roles. A wide range of platforms were under consideration, including everything from low-end AT-6 Wolverine and A-29 Super Tucano turboprops and the Textron AirLand Scorpion as more basic off-the-shelf options to more sophisticated clean-sheet attack aircraft or "AT-X" derivatives of the T-X next-generation trainer as entirely new attack platforms.[131][135][136]

In January 2016, the USAF was "indefinitely freezing" plans to retire the A-10 for at least several years. In addition to Congressional opposition, its use in anti-ISIL operations, deployments to Eastern Europe as a response to Russia's military intervention in Ukraine, and reevaluation of F-35 numbers necessitated its retention.[137][138] In February 2016, the Air Force deferred the final retirement of the aircraft until 2022 after being replaced by F-35s on a squadron-by-squadron basis.[139][140] In October 2016, the Air Force Material Command brought the depot maintenance line back to full capacity in preparation for re-winging the fleet.[141] In June 2017, it was announced that the aircraft "...will now be kept in the air force’s inventory indefinitely."[142][5]

Other uses

On 25 March 2010, an A-10 conducted the first flight of an aircraft with all engines powered by a biofuel blend. The flight, performed at Eglin Air Force Base, used a 1:1 blend of JP-8 and Camelina-based fuel.[143] On 28 June 2012, the A-10 became the first aircraft to fly using a new fuel blend derived from alcohol; known as ATJ (Alcohol-to-Jet), the fuel is cellulosic-based and can be produced using wood, paper, grass, or any cellulose based material, which are fermented into alcohols before being hydro-processed into aviation fuel. ATJ is the third alternative fuel to be evaluated by the Air Force as a replacement for the petroleum-derived JP-8 fuel. Previous types were a synthetic paraffinic kerosene derived from coal and natural gas and a bio-mass fuel derived from plant-oils and animal fats known as Hydroprocessed Renewable Jet.[144]

In 2011, the National Science Foundation granted $11 million to modify an A-10 for weather research for CIRPAS at the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School[145] and in collaboration with scientists from the South Dakota School of Mines & Technology (SDSM&T),[146] replacing SDSM&T's retired North American T-28 Trojan.[147] The A-10's armor is expected to allow it to survive the extreme meteorological conditions, such as 200 mph hailstorms, found in inclement high-altitude weather events.[148]

Variants

- YA-10A

- Pre-production variant. 12 were built.[149]

- A-10A

- Single-seat close air support, ground-attack production version.

- OA-10A

- A-10As used for airborne forward air control.

- YA-10B Night/Adverse Weather (N/AW)

- Two-seat experimental prototype, for work at night and in bad weather. The one YA-10B prototype was converted from an A-10A.[150][151]

- A-10C

- A-10As updated under the incremental Precision Engagement (PE) program.[43]

- A-10PCAS

- Proposed unmanned version developed by Raytheon and Aurora Flight Sciences as part of DARPA's Persistent Close Air Support program.[152] The PCAS program eventually dropped the idea of using an optionally manned A-10.[153]

- Civilian A-10

- Proposed by the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology to replace its North American T-28 Trojan thunderstorm penetration aircraft. The A-10 would have its military engines, avionics, and oxygen system replaced by civilian versions. The engines and airframe would receive protection from hail, and the GAU-8 Avenger would be replaced with ballast or scientific instruments.[154]

Operators

.jpg.webp)

The A-10 has been flown exclusively by the United States Air Force and its Air Reserve components, the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) and the Air National Guard (ANG). As of 2017, 282 A-10C aircraft are reported as operational, divided as follows: 141 USAF, 55 AFRC, 86 ANG.[155]

- United States Air Force

- Air Force Materiel Command

- 514th Flight Test Squadron (Hill AFB, Utah) (1993-)

- 23rd Wing

- 74th Fighter Squadron (Moody AFB, Georgia) (1980-1992, 1996-)

- 75th Fighter Squadron (Moody AFB, Georgia) (1980-1991, 1992-)

- 51st Fighter Wing

- 25th Fighter Squadron (Osan AFB, South Korea) (1982-1989, 1993-)

- 53d Wing

- 422d Test and Evaluation Squadron (Nellis AFB, Nevada) (1977-)

- 57th Wing

- 66th Weapons Squadron (Nellis AFB, Nevada) (1977-1981, 2003-)

- 96th Test Wing

- 40th Flight Test Squadron (Eglin AFB, Florida) (1982-)

- 122nd Fighter Wing (Indiana ANG)

- 163d Fighter Squadron (Fort Wayne ANGS, Indiana) (2010-)

- 124th Fighter Wing (Idaho ANG)

- 190th Fighter Squadron (Gowen Field ANGB, Idaho) (1996-)

- 127th Wing (Michigan ANG)

- 107th Fighter Squadron (Selfridge ANGB, Michigan) (2008-)

- 175th Wing (Maryland ANG)

- 104th Fighter Squadron (Warfield ANGB, Maryland) (1979-)

- 355th Fighter Wing

- 354th Fighter Squadron (Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona) (1979-1982, 1991-)

- 357th Fighter Squadron (Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona) (1979-)

- 442nd Fighter Wing (AFRC)

- 303d Fighter Squadron (Whiteman AFB, Missouri) (1982-)

- 476th Fighter Group (AFRC)

- 76th Fighter Squadron (Moody AFB, Georgia) (1981-1992, 2009-)

- 495th Fighter Group (AFRC)

- 358th Fighter Squadron (Whiteman AFB, Missouri) (1979-2014, 2015-)

- 924th Fighter Group (AFRC)

- 45th Fighter Squadron (Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona) (1981-1994, 2009-)

- 47th Fighter Squadron (Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona) (1980-)

- 926th Wing (AFRC)

- 706th Fighter Squadron (Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona) (1982-1992, 1997-)

- Air Force Materiel Command

Former squadrons

- 18th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1982-1991)

- 23d Tactical Air Support Squadron (1987-1991) (OA-10 unit)

- 55th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1994-1996)

- 70th Fighter Squadron (1995-2000)

- 78th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1979-1992)

- 81st Fighter Squadron (1994-2013)

- 91st Tactical Fighter Squadron (1978-1992)

- 92d Tactical Fighter Squadron (1978-1993)

- 103d Fighter Squadron (Pennsylvania ANG) (1988-2011) (OA-10 unit)

- 118th Fighter Squadron (Connecticut ANG) (1979-2008)

- 131st Fighter Squadron (Massachusetts ANG) (1979-2007)

- 138th Fighter Squadron (New York ANG) (1979-1989)

- 172d Fighter Squadron (Michigan ANG) (1991-2009)

- 176th Tactical Fighter Squadron (Wisconsin ANG) (1981-1993)

- 184th Fighter Squadron (Arkansas ANG) (2007-2014)

- 353d Tactical Fighter Squadron (1978-1992)

- 355th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1978-1992, 1993–2007)

- 356th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1977-1992)[156]

- 509th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1979-1992)

- 510th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1979-1994)

- 511th Tactical Fighter Squadron (1980-1992)

Aircraft on display

United Kingdom

- A-10A

- 77-0259 – American Air Museum at Imperial War Museum Duxford[159]

- 80-0219 – Bentwaters Cold War Museum[160]

United States

- YA-10A

- 71-1370 – Joint Base Langley-Eustis (Langley AFB), Hampton, Virginia[161]

- YA-10B

- A-10A

- 73-1666 – Hill Aerospace Museum, Hill AFB, Utah[163]

- 73-1667 – Flying Tiger Heritage Park at the former England AFB, Louisiana[164]

- 75-0263 – Empire State Aerosciences Museum, Glenville, New York[165]

- 75-0270 – McChord Air Museum, McChord AFB, Washington[166]

- 75-0293 – Wings of Eagles Discovery Center, Elmira, New York[167]

- 75-0288 – Air Force Armament Museum, Eglin AFB, Florida[168]

- 75-0289 – Heritage Park, Eielson AFB, Alaska[169]

- 75-0298 – Pima Air & Space Museum (adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB), Tucson, Arizona[170]

- 75-0305 – Museum of Aviation, Robins AFB, Warner Robins, Georgia[171]

- 75-0308 – Moody Heritage Park, Moody AFB, Valdosta, Georgia[172]

- 75-0309 – Shaw AFB, Sumter, South Carolina. Marked as AF Ser. No. 81-0964 assigned to the 55 FS from 1994 to 1996. The represented aircraft was credited with downing an Iraqi Mi-8 Hip helicopter on 15 Feb 1991 while assigned to the 511 TFS.[173][174]

- 76-0516 – Wings of Freedom Aviation Museum at the former NAS Willow Grove, Horsham, Pennsylvania[175]

- 76-0530 – Whiteman AFB, Missouri[176]

- 76-0535 – Cradle of Aviation, Garden City, New York[177]

- 76-0540 – Aerospace Museum of California, McClellan Airport (former McClellan AFB), Sacramento, California[178]

- 77-0199 – Stafford Air & Space Museum, Weatherford, Oklahoma

- 77-0205 – USAF Academy collection, Colorado Springs, Colorado[179]

- 77-0228 – Grissom Air Museum, Grissom ARB (former Grissom AFB), Peru, Indiana[180]

- 77-0244 – Wisconsin Air National Guard Museum, Volk Field ANGB, Wisconsin[181]

- 77-0252 – Cradle of Aviation, Garden City, New York (nose section only)[182]

- 77-0667 – England AFB Heritage Park, Alexandria, Louisiana[183]

- 78-0681 – National Museum of the United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson AFB, Dayton, Ohio[184]

- 78-0687 – Don F. Pratt Memorial Museum, Fort Campbell, Kentucky[185]

- 79-0097 – Warbird Park, former Myrtle Beach Air Force Base, South Carolina[186]

- 79-0100 – Barnes Air National Guard Base, Westfield, Massachusetts[187]

- 79-0103 – Bradley Air National Guard Base, Windsor Locks, Connecticut[188]

- 79-0116 – Warrior Park, Davis-Monthan AFB, Tucson, Arizona[189]

- 79-0173 – New England Air Museum, Windsor Locks, Connecticut[190]

- 80-0247 – American Airpower Museum, Republic Airport, Farmingdale, New York[191]

- 80-0708 – Selfridge Military Air Museum, Selfridge Air National Guard Base, Harrison Township, Michigan[192]

Specifications (A-10A)

Data from The Great Book of Modern Warplanes,[193] Fairchild-Republic A/OA-10,[194] USAF[81]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 53 ft 4 in (16.26 m)

- Wingspan: 57 ft 6 in (17.53 m)

- Height: 14 ft 8 in (4.47 m)

- Wing area: 506 ft2 (47.0 m2)

- Airfoil: NACA 6716 root, NACA 6713 tip

- Empty weight: 24,959 lb (11,321 kg)

- Loaded weight: 30,384 lb (13,782 kg)

CAS mission: 47,094 lb (21,361 kg)

Anti-armor mission: 42,071 lb (19,083 kg) - Max. takeoff weight: 50,000 lb[195] (22,700 kg)

- Internal fuel capacity: 11,000 lb (4,990 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric TF34-GE-100A turbofans, 9,065 lbf (40.32 kN) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 381 knots (439 mph, 706 km/h) at sea level, clean[194]

- Cruise speed: 300 knots (340 mph, 560 km/h)

- Stall speed: 120 knots (138 mph, 220 km/h) [196]

- Never exceed speed: 450 knots (518 mph,[194] 833 km/h) at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) with 18 Mk 82 bombs[197]

- Combat radius:

- Ferry range: 2,240 nmi (2,580 mi, 4,150 km) with 50 knot (55 mph, 90 km/h) headwinds, 20 minutes reserve

- Service ceiling: 45,000 ft (13,700 m)

- Rate of climb: 6,000 ft/min (30 m/s)

- Wing loading: 99 lb/ft2 (482 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.36

Armament

- Guns: 1× 30 mm (1.18 in) GAU-8/A Avenger rotary cannon with 1,174 rounds (original capacity was 1,350 rd)

- Hardpoints: 11 (8× under-wing and 3× under-fuselage pylon stations) with a capacity of 16,000 lb (7,260 kg) and provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets:

- Missiles:

- 2× AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles for self-defense

- 6× AGM-65 Maverick air-to-surface missiles

- Bombs:

- Mark 80 series of unguided iron bombs or

- Mk 77 incendiary bombs or

- BLU-1, BLU-27/B, CBU-20 Rockeye II, BL755[201] and CBU-52/58/71/87/89/97 cluster bombs or

- Paveway series of Laser-guided bombs or

- Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) (A-10C)[202] or

- Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser (A-10C)

- Other:

- SUU-42A/A Flares/Infrared decoys and chaff dispenser pod or

- AN/ALQ-131 or AN/ALQ-184 ECM pods or

- Lockheed Martin Sniper XR or LITENING targeting pods (A-10C) or

- 2× 600 US gal (2,300 L) Sargent Fletcher drop tanks for increased range/loitering time.

- Rockets:

Avionics

- AN/AAS-35(V) Pave Penny laser tracker pod[203] (mounted beneath right side of cockpit) for use with Paveway LGBs (currently the Pave Penny is no longer in use)

- Head-up display (HUD)[31]

Notable appearances in media

Nicknames

The A-10 Thunderbolt II received its popular nickname "Warthog" from the pilots and crews of the USAF attack squadrons who flew and maintained it. The A-10 is the last of Republic's jet attack aircraft to serve with the USAF. The Republic F-84 Thunderjet was nicknamed the "Hog", F-84F Thunderstreak nicknamed "Superhog", and the Republic F-105 Thunderchief tagged "Ultra Hog".[204] The saying Go Ugly Early has been associated with the aircraft in reference to calling in the A-10 early to support troops in ground combat.[205]

See also

- Craig D. Button – USAF pilot who crashed mysteriously in an A-10

- 190th Fighter Squadron, Blues and Royals friendly fire incident

- 1988 Remscheid A-10 crash

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- With the inner wheel on a turn stopped, the minimum radius of the turn is dictated by the distance between the inner wheel and the nose wheel. Since the distance is less between the right main wheel and the nose gear than the same measurement on the left, the aircraft can turn more tightly to the right.

Citations

- Spick 2000, p. 51.

- Spick 2000, pp. 17, 52.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 42.

- "Fairchild Republic A-10A Thunderbolt II" Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine. National Museum of the US Air Force

- Keller, Jared (8 June 2017). "Fighter Pilot Turned Congresswoman Throws Wrench in Quiet Plans To Cut A-10 Squadrons". Task & Purpose. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

Air Force R&D Chief Lt. General Arnold Bunch testified that the service "is committed to maintaining a minimum of six A-10 combat squadrons flying and contributing to the fight through 2030 [with] additional A-10 force structure is contingent on future budget levels and force structure requirements.

- Piehler, G. Kurt, ed. (2013). Encyclopedia of Military Science. associate editor: M. Houston Johnson. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1412969338.

- Knaack 1978, p. 151.

- Hobson, Chris (2001). Vietnam Air Losses, USAF/USN/USMC, Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast Asia, 1961–1973. Specialty Press. ISBN 978-1-85780-115-6.

- Jacques & Strouble 2010.

- Burton 1993

- Coram 2004

- Knaack 1978, pp. 265–76.

- NATO. "A Pledge for Peace and Progress". Canadian War Museum. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2016.

- Jacques & Strouble 2010, p. 24.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 12.

- Coram 2004, p. 235.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 16–17.

- "GAO-07-415: Tactical Aircraft, DOD Needs a Joint and Integrated Investment Strategy." Archived 14 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Government Accountability Office, April 2007. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 19.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 18, 20.

- Spick 2000, p. 18.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 21.

- Pike, Chris. "A-10/OA-10 Thunderbolt II." Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 18 July 2010.

- "Fact Sheet: Republic Night/Adverse Weather A-10." Archived 14 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 18 July 2010.

- Spick 2000, pp. 52–55.

- "Aircraft inventory". Flight Test Historical Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- Spick 2000, p. 48.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 652.

- Spick 2000, p. 49.

- Donald and March 2004, p. 46.

- Jensen, David. "All New Warthog." Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine Avionics Magazine, 1 December 2005.

- "Fairchild A-10 Thunderbolt II". Military Aircraft Forecast. Forecast International. 2002. Archived from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Garland & Colombi 2010, pp. 192–93.

- Garland & Colombi 2010, pp. 193–94.

- Jacques, David (23 October 2008). "Sustaining Systems Engineering: The A-10 Example (Based on A-10 Systems Engineering Case Study)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- "Boeing Awarded $2 Billion A-10 Wing Contract." Boeing, 29 June 2007. Retrieved 1 July 2011. Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Drew, James (4 February 2016). "USAF to continue A-10 'Warthog' wing production". FlightGlobal. Reed Business. Archived from the original on 8 April 2018. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

The same day, the air force released a draft statement of work regarding construction of slightly updated versions of the A-10 enhanced wing assembly currently built by Boeing and Korean Aerospace Industries. Boeing’s contract includes 173 wings with options for 69 more, but the air force confirms that ordering period ends in September. Boeing has said those wings, based on 3D models of the original thick-skin wing design of the 1970s, could keep the aircraft flying past 2040.

- Tirpak, John A. "Making the Best of the Fighter Force." Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Air Force magazine, Vol. 90, no. 3, March 2007.

- "US Air Force to Build 56 Additional A-10 Wings to Keep the Type Operating Through 2035" Archived 11 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Deagel.com, 4 September 2013.

- "Air Force Budget Proposal Preserves Cherished Modernization Programs" Archived 23 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nationaldefensemagazine.org, 4 March 2014.

- "A-10: Been There, Considered That" Archived 24 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Airforcemag.com, 24 April 2014.

- "Boeing discussing international A-10 Warthog sales." Archived 22 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Flightglobal.com, 20 May 2015.

- Schanz, Marc V. "Not Fade Away." Archived 10 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, June 2008. Retrieved: 9 October 2016.

- "A Higher-Tech Hog: The A-10C PE Program." Archived 24 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily, 21 July 2010. Retrieved: 11 June 2011.

- "Defence & Security Intelligence & Analysis". IHS Jane's 360 (janes.com). Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Orndorff, Bill. "Maintenance unit completes upgrade of 100th A-10." Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Air Force, 14 January 2008. Retrieved: 10 October 2016.

- "A-10 Precision Engagement program holds its final roll-out ceremony." Archived 20 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Hilltop Times via Ogden Publishing Corporation, 14 January 2008. Retrieved: 10 October 2016.

- "A-10C Capabilities Briefing" Archived 20 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force via media.jrn.com. Retrieved: 22 December 2016.

- Majumdar, Dave. "Air Force Reluctantly Upgrades A-10s After Congress Complains." Archived 27 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine War is Boring blog

- Liveoak, Brian. "AFSO21 Event for Osan's A-10 Phase Dock" (PDF). The Exceptional Release (Winter 2014): 28. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- 40th FTS expands A-10 fuel limitations in combat Archived 1 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Eglin.AF.mil, 26 August 2013

- Donald and March 2004, p. 8.

- Air International, May 1974, p. 224.

- Drendel 1981, p. 12.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal. Spring 1994, p. 64.

- Taylor 1982, pp. 363–64.

- Spick 2000, pp. 64–65.

- "Fairchild Republic A-10A Thunderbolt II". Air Force National Museum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- Donald and March 2004, p. 18.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 58.

- Spick 2000, p. 44.

- Henderson, Breck W. "A-10 'Warthogs' damaged heavily in Gulf War bug survived to fly again." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 5 August 1991.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 47, 49.

- Spick 2000, p. 32.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal Spring 1994, p. 42.

- Air International June 1979, p. 270.

- Spick 2000, pp. 30–33.

- Haag, Jason. "Wounded Warthog: an A-10 Thunderbolt II pilot safely landed her "Warthog" after it sustained significant damage from enemy fire." Archived 9 July 2012 at Archive.today Combat Edge, April 2004.

- "Capt. Kim Campbell." stripes.com. Retrieved: 21 August 2011.

- Bell 1986, p. 64.

- Wilson 1976, p. 714.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II". U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Stephens 1995, p. 18.

- TCTO 1A-10-1089, Flight manual TO 1A-10A-1 (20 February 2003, Change 8), pp. vi, 1–150A.

- Sweetman 1987, p. 46.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 64–73.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal Spring 1994, pp. 53–54.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal, Spring 1994, pp. 54–56.

- "Tłumacz Google". translate.google.pl.

- Stephens. World Air Power Journal, Spring 1994, p. 53.

- "Fact Sheet: A-10 Thunderbolt II". USAF. 22 September 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II". U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- Neubeck 1999, p. 92.

- Neubeck 1999, pp. 72–73, 76–77.

- Shaw 1985, p. 382.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal, Spring 1994, p. 47.

- Spick 2000, p. 21.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 42, 56–59.

- Campbell 2003, pp. 117, 175–83.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 63.

- Stephens World Air Power Journal, Spring 1994, pp. 50, 56.

- Haulman, Daniel L. "Crisis in Grenada: Operation Urgent Fury" (PDF). Air Force Historical Support Division, US Air Force. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 October 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Peeters, Sander. "Grenada, 1983: Operation "Urgent Fury"". acig.info. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "Factsheets: Operation Urgent Fury". af.mil. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Coyne, James P. (June 1992). "Total Storm", Air Force magazine. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- Frantz, Douglas (8 February 1991). "Pilot Chalks Up First 'Warthog' Air Kill" Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "Fixed-wing Combar Aircraft Attrition, list of Gulf War fixed-wing aircraft losses." Gulf War Airpower Survey, Vol. 5, 1993. Retrieved: 24 October 2014. Archived 16 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Friedman, Norman. "Desert Victory." World Air Power Journal.

- "A-10/OA-10 fact sheet." Archived 30 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Air Force, October 2007. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- "A-16 Close Air Support." Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine F-16.net. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck. "U.S. Hits Bosnian Serb Target in Air Raid." Archived 7 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 6 August 1994.

- Donald and March 2004, pp. 42–43.

- "Pilot Gets 2nd Chance to Thank Rescuer." Air Force Times, 27 April 2009.

- Haave |, Col. Christopher and Lt. Col. Phil M. Haun. "A-10s over Kosovo." Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama, December 2003. Retrieved: 21 August 2011.

- Donald and March 2004, p. 44.

- Donald and March 2004, pp. 44–45.

- "30 Apr OIF by the Numbers UNCLASS.doc (pdf)." Archived 13 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Maier, Staff Sgt. Markus. "Upgraded A-10s prove worth in Iraq." U.S. Air Force, 7 November 2007. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Doscher, Staff Sgt. Thomas J. "A-10C revolutionizes close air support." Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Air Force, 21 February 2008. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- "Fight to Keep A-10 Warthog in Air Force Inventory Reaches End Game" Archived 7 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Nationaldefensemagazine.org, September 2013.

- "Air Force, lawmakers clash over future of A-10 again" Archived 30 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Militarytimes.com, 29 April 2014.

- "New air missions attack Kadhafi troops: Pentagon." Archived 29 March 2011 at WebCite AFP, 29 March 2011.

- Schmitt, Eric "U.S. Gives Its Air Power Expansive Role in Libya." Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 29 March 2011, p. A13. Retrieved: 29 March 2011.

- 122nd Fighter Wing deploying 300 airmen to Mideast Archived 24 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Journalgazette.net, 17 September 2014

- "Pentagon to deploy 12 A-10s to Middle East". TheHill. Archived from the original on 7 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "House Dem: A-10 jets crucial to ISIS fight". TheHill. Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "A-10s Hitting ISIS Targets in Iraq" Archived 18 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Military.com, 17 December 2014

- "A-10 attacking Islamic State targets in Iraq" Archived 19 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Militarytimes.com, 19 December 2014

- "A-10 Performing 11 Percent of Anti-ISIS Sorties". Defensenews.com, 19 January 2015

- "US A-10 Attack Planes Hit ISIS Oil Convoy to Crimp Terror Funding" Archived 20 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Military.com, 16 November 2015.

- "Air Force deploys A-10s to Afghanistan to ramp up Taliban fight". Fox News. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- Trimble, Steven. "US Air Force may extend Fairchild A-10 life beyond 2028." Archived 20 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 29 August 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- Goozner, Merill. "$382 Billion for a Slightly Better Fighter Plane?: F-35 has plenty of support in Congress." Archived 12 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Fiscal Times, 11 February 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2011

- "F-35B cannot generate enough sorties to replace A-10" Archived 19 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Flight global, 16 May 2012.

- "USAF Weighs Scrapping KC-10, A-10 Fleets." Defense News, 15 September 2013.

- "USAF General: A-10 Fleet Likely Done if Sequestration Continues." Defense News, 17 September 2013.

- Army Not Interested in Taking A-10 Warthogs from Air Force Archived 26 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine DoD Buzz, 25 January 2015

- "A-10: Close Air Support Wonder Weapon or Boneyard Bound?", Breaking defense, 19 December 2013, archived from the original on 22 December 2013, retrieved 22 December 2013.

- Pentagon Unveils Program to Help Build 6th Generation Fighter Archived 30 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine – DoD Buzz, 28 January 2015

- Air Force considering A-10 replacement for future close air support Archived 13 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Flight global, 13 February 2015

- One-week study re-affirms A-10 retirement decision: USAF Archived 18 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal, 6 March 2015

- "USAF rules out international A-10 sales" Archived 26 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Flightglobal.com, 24 July 2015.

- Drew. James. "A-10 replacement? USAF strategy calls for 'future CAS platform'" FlightGlobal, August 2015. Archive

- "Strategy 2015: Securing the High Ground" (PDF). Air Combat Command, US Air Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- USAF studying future attack aircraft options Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 9 March 2016

- Osborn, Kris. "The Air Force Will Build a New A-10-like Close Air Support Aircraft". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- Report: A-10 retirement indefinitely delayed – Airforcetimes.com, 13 January 2016

- Brad Lendon, CNN (21 January 2016). "ISIS may have saved the A-10". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2016.

- DOD reveals 'arsenal plane' and microdrones in budget speech Archived 3 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 2 February 2016

- Bennett, Jay (19 September 2016). "The A-10 Retirement Could Be Delayed Yet Again". Popular Mechanics. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Bennett, Jay (25 October 2016). "Air Force Fires Up the A-10 Depot Line to Keep Warthogs Flying 'Indefinitely'". popularmechanics.com. Hearst Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- Haynes, Deborah (9 June 2017). "A-10 Warthog a 'badass plane with a big gun' saved from scrapheap". The Australian. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- Graham, Ian. "Air Force scientists test, develop bio jet fuels." af.mil, 30 March 2010. Retrieved: 18 July 2010.

- 46th tests alcohol-based fuel in A-10 Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Eglin.AF.mil, 2 July 2012

- "NSF to Turn Tank Killer Into Storm Chaser" Archived 11 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine Science, 11 November 2011. Retrieved: 22 July 2012.

- Dept. of Atmospheric and Environmental Sciences, Research Facilities: A10 Storm Penetrating Aircraft Archived 21 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine South Dakota School of Mines & Technology. Retrieved: 20 February 2017.

- "T-28 Instrumented Research Aircraft" Archived 1 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine South Dakota School of Mines & Technology. Retrieved: 22 July 2012.

- "Plane Has Combative Attitude toward Storms" Archived 30 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. American Meteorological Society, 8 December 2011. Retrieved: 4 May 2013.

- Donald and March 2004, pp. 9–10.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 92–93.

- Donald and March 2004, pp. 12, 16.

- "Unmanned version of A-10 on way." Archived 23 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine SpaceDaily.com, 20 February 2012.

- "Darpa Refocuses Precision Close Air Support Effort On Manned Aircraft" Archived 23 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Aviation Week, 10 September 2013

- "Next-generation Storm-penetrating Aircraft" (PDF). South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (2018). The Military Balance. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-1857439557.

- First unit to become operational with the A-10.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0264." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/76-0505." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "Welcome to the American Air Museum Home Page". iwm.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- "Bentwaters Cold War Museum". bcwm.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/71-1370." Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/73-1664." Archived 2 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Flight Test Center Museum. Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/73-1666." Archived 23 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Hill Aerospace Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/73-1667." Archived 23 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0263." Archived 29 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Empire State Aerosciences Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0270." Archived 24 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine McChord Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0293." Archived 2 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Wings of Eagles Discovery Center. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0288." Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Armament Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0289." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0298." Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Pima Air & Space Museum. Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0305." Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Museum of Aviation. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0308." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/75-0309." Archived 4 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "The last strike: A-10 Thunderbolt II preserved in Shaw's Air Park". af.mil. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/76-0516." Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Wings of Freedom Museum. Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "Team Whiteman recovers A-10 aircraft." Archived 2 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Whiteman AFB. Retrieved: 21 July 2011.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/76-0535." Archived 25 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Cradle of Aviation. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/76-0540." Archived 7 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Aerospace Museum of California. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0205." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0228." Archived 13 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Grissom Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0244." Archived 23 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0252." Archived 25 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine Cradle of Aviation. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/77-0667." Archived 7 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine "England AFB Heritage Park." Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/78-0681." Archived 26 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the USAF. Retrieved: 29 August 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/78-0687." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/79-0079." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/79-0100." Archived 2 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/79-0103." Archived 2 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/79-0116." Archived 13 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II." Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine New England Air Museum. Retrieved: 5 April 2013.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/80-0247." Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine American Airpower Museum. Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- "A-10 Thunderbolt II/80-0708." Archived 2 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Selfridge Military Air Museum. Retrieved: 1 July 2015.

- Spick 2000, pp. 21, 44–48.

- Jenkins 1998, p. 54.

- Donald, David, ed. The Complete Encyclopedia of World Aircraft, pp. 391–392. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7607-0592-5.

- Aalbers, Willem "Palerider". "History of the Fairchild-Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II, Part Two." Archived 4 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine Simhq.com. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Flight manual TO 1A-10A-1 (20 February 2003, Change 8), pp. 5–24.

- "U.S. Air Force Deploys APKWS Laser-Guided Rockets on F-16s". baesystems.com. BAE. 8 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Flight manual TO 1A-10A-1 (15 March 1988, Change 8), pp. 5-28, 5–50.

- Flight manual TO 1A-10C-1 (2 April 2012, Change 10), pp. 5-33, 5–49.

- Flight Manual TO 1A-10A-1 (20 February 2003, Change 8), pp. 5–30.

- Pike, John. "A-10 Specs." Archived 18 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine Global Security. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- "Lockheed Martin AN/AAS-35(V) Pave Penny laser tracker." Jane's Electro-Optic Systems, 5 January 2009. Retrieved: 5 March 2010.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 4, backcover.

- Jenkins 1998, pp. 64–65.

Bibliography

- Bell, Dana. A-10 Warthog in Detail & Scale, Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: TAB Books, 1986. ISBN 0-8168-5030-5.

- Burton, James G. The Pentagon Wars: Reformers Challenge the Old Guard, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1993. ISBN 1-55750-081-9.