Geography of Turkey

Turkey is a large, roughly rectangular peninsula[5] that bridges southeastern Europe and Asia. Thrace, the European portion of Turkey comprises 3%[6] of the country and 10%[7] of its population. Thrace is separated from Asia Minor, the Asian portion of Turkey, by the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles.[8]

| |

| Continent | Asia and Europe |

|---|---|

| Region | Western Asia and Southeastern Europe |

| Coordinates | 39°00′N 35°00′E |

| Area | Ranked 36th |

| • Total | 783,562 km2 (302,535 sq mi) |

| • Land | 98% |

| • Water | 2% |

| Coastline | 7,200 km (4,500 mi) |

| Borders | Total land borders: 2648 km Armenia 268 km, Azerbaijan 9 km, Bulgaria 240 km, Georgia 252 km, Greece 206 km, Iran 499 km, Iraq 352 km, Syria 822 km |

| Highest point | Mount Ağrı (Ararat) 5,137 m |

| Lowest point | Mediterranean Sea 0 m |

| Longest river | Kızılırmak 1,350 km |

| Largest lake | Van 3,755 km2 (1,449.81 sq mi) |

| Exclusive economic zone | 261,654 km2 (101,025 sq mi)[1][2][3][4] |

External boundaries

Turkey, surrounded by water on three sides, has well-defined natural borders with its eight neighbors.[9]

Turkey’s frontiers with Greece—206 kilometers—and Bulgaria—240 kilometers— were settled[10] by Treaty of Constantinople (1913) and later confirmed[11] by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. The 1921 treaties of Moscow[12] and Kars with the Soviet Union[13] defines Turkey’s current borders with Armenia (268 kilometers), Azerbaijan (nine kilometers), and Georgia (252 kilometers). The 499-kilometer Iranian border was first settled by the 1639 Treaty of Kasr-ı Şirin and confirmed in 1937.[14] With the exception of Mosul, Turkey ceded the territories of the present-day Iraq and Syria with the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. In 1926, Turkey ceded Mosul to the United Kingdom in exchange for 10% the oil revenues from Mosul for 25 years.[15] Syria does not recognize its border with Turkey because of a dispute of the 1939 transfer of Hatay Province following a referendum that favored union with Turkey.[16]

Regions

The 1st Geography Congress, held in Ankara City between 6–21 June 1941, divided Turkey into seven regions after long discussions and work.[17] These geographical regions were separated according to their climate, location, flora and fauna, human habitat, agricultural diversities, transportation, topography, etc.[17] At the end, 4 coastal regions and 3 inner regions were named according to their proximity to the four seas surrounding Turkey, and their positions in Anatolia.[17]

Black Sea Region

[[KackarDagi_fromNorth_hory.jpg|thumb|left|Kaçkar Mountains

The physical geography of the Black Sea Region landscapes is characterized by the mountain range forming a barrier parallel with the Black Sea Coast and high humidity[18] and precipitation.[19] The Eastern Black Sea Region presents alpine landscapes[20] with steep and densely forested slopes. Steep slopes, as a morphological feature, occur both under the sea, and in the mountain ranges, with the sea floor at below 2000 m[21] along a line from Trabzon to the Turkish–Georgian border, and the mountains quickly reaching over 3000 m, with a maximum of 3971[22] m in Kaçkar Peak. The parallel valleys running north to the Black Sea used to be isolated from one another until a few decades ago because the densely forested ridges made transportation and exchange very difficult.[23] This allowed for the development of a strong cultural[24] identity— the “Laz” language, music and dance—linked to this specific geographic context.

From west to east, the main rivers of the region are the Sakarya (824 km), the Kızılırmak River (1355 km, the longest river of Turkey), the Yeşilırmak (418 km) and the Çoruh (376 km).[25]

Year-round high[26] precipitations—varying from 580 m/year in the west to more than 2200[27] generate dense forests, with oak, beech family trees, hazel (Corylus avellana), hornbeam (Carpinus betulus) and sweet chesnut (Castanea sativa) prevailing.[28]

Isolated from one another because of steep valleys,[29] the Black Sea Region includes 850[30] plant taxa of which 116[31] is endemic to the area, and of which 12 are endangered[32] and 19[33] vulnerable. Hazelnut is a native species[34] for this region, which covers 70 and 82%[35] of the world’s production and exports respectively.

The Kaçkar Range at altitudes of 3000 m and above is heavily glaciated (see map on the right)[36] owing to the suitable geomorphological- climatological conditions[37] during the Pleistocene.

Marmara Region

The European portion of Turkey consists mainly of rolling plateau country well suited to agriculture. It receives about 520 millimeters of rainfall annually.

Densely populated, this area includes the cities of Istanbul and Edirne. The Bosphorus, which links the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, is about twenty-five kilometers long and averages 1.5 kilometers in width but narrows in places to less than 1,000 meters. There are two suspension bridges over the Bosphorus, both its Asian and European banks rise steeply from the water and form a succession of cliffs, coves, and nearly landlocked bays. Most of the shores are densely wooded and are marked by numerous small towns and villages. The Dardanelles (ancient Hellespont) strait, which links the Sea of Marmara (ancient Propontis) and the Aegean Sea, is approximately forty kilometers long and increases in width toward the south. Unlike the Bosphorus, the Dardanelles has fewer settlements along its shores. The Saros Bay is located near the Gallipoli peninsula and is disliked because of dirty beaches. It is a favourite spot among scuba divers for the richness of its underwater fauna and is becoming increasingly popular due to its vicinity to Istanbul.

The most important valleys are the Kocaeli Valley, the Bursa Ovası (Bursa Basin), and the Plains of Troy (historically known as the Troad). The valley lowlands around Bursa is densely populated.

Aegean Region

Located on the western side of Anatolia, the Aegean region has a fertile soil and a typically Mediterranean climate; with mild, wet winters and hot, dry summers. The broad, cultivated valley lowlands contain about half of the country's richest farmlands.

The largest city in the Aegean Region of Turkey is İzmir, which is also the country's third largest city and a major manufacturing center; as well as its second largest port after Istanbul.

Olive and olive oil production is particularly important for the economy of the region. The seaside town of Ayvalık and numerous towns in the provinces of Balıkesir, İzmir and Aydın are particularly famous for their olive oil and related products; such as soap and cosmetics.

The region also has many important centers of tourism which are known both for their historic monuments and for the beauty of their beaches; such as Assos, Ayvalık, Bergama, Foça, İzmir, Çeşme, Sardis, Ephesus, Kuşadası, Didim, Miletus, Bodrum, Marmaris, Datça and Fethiye.

Mediterranean Region

Toward the east, the extensive Çukurova Plain (historically known as the Cilician Plain) around Adana, Turkey's fifth most populous city, consist largely of reclaimed flood lands. In general, rivers have not cut valleys to the sea in the western part of the region. Historically, movement inland from the western Mediterranean coast was difficult. East of Adana, much of the coastal plain has limestone features such as collapsed caverns and sinkholes. Between Adana and Antalya, the Taurus Mountains rise sharply from the coast to high elevations. Other than Adana, Antalya, and Mersin, the Mediterranean coast has few major cities, although it has numerous farming villages.

Paralleling the Mediterranean coast, the Taurus Mountains (Turkish: Toros Dağları) are Turkey's second chain of folded mountains. The range rises just inland from the coast and trends generally in an easterly direction until it reaches the Arabian Platform, where it arcs around the northern side of the platform. The Taurus Mountains are more rugged and less dissected by rivers than the Pontic Mountains and historically have served as a barrier to human movement inland from the Mediterranean coast except where there are mountain passes such as the historic Cilician Gates (Gülek Pass), northwest of Adana.

Central Anatolia Region

Stretching inland from the Aegean coastal plain, the Central Anatolia Region occupies the area between the two zones of the folded mountains, extending east to the point where the two ranges converge. The plateau-like, semi-arid highlands of Anatolia are considered the heartland of the country. The region varies in elevation from 700 to 2000 meters from west to east. Mount Erciyes is the peak at 3916 meters. The two largest basins on the plateau are the Konya Ovası and the basin occupied by the large salt lake, Tuz Gölü. Both basins are characterized by inland drainage. Wooded areas are confined to the northwest and northeast of the plateau. Rain-fed cultivation is widespread, with wheat being the principal crop. Irrigated agriculture is restricted to the areas surrounding rivers and wherever sufficient underground water is available. Important irrigated crops include barley, corn, cotton, various fruits, grapes, opium poppies, sugar beets, roses, and tobacco. There also is extensive grazing throughout the plateau.

Central Anatolia receives little annual rainfall. For instance, the semi-arid center of the plateau receives an average yearly precipitation of only 300 millimeters. However, actual rainfall from year to year is irregular and occasionally may be less than 200 millimeters, leading to severe reductions in crop yields for both rain-fed and irrigated agriculture. In years of low rainfall, stock losses also can be high. Overgrazing has contributed to soil erosion on the plateau. During the summers, frequent dust storms blow a fine yellow powder across the plateau. Locusts occasionally ravage the eastern area in April and May. In general, the plateau experiences extreme heat, with almost no rainfall in summer and cold weather with heavy snow in winter.

Frequently interspersed throughout the folded mountains, and also situated on the Anatolian Plateau, are well-defined basins, which the Turks call ova. Some are no more than a widening of a stream valley; others, such as the Konya Ovası, are large basins of inland drainage or are the result of limestone erosion. Most of the basins take their names from cities or towns located at their rims. Where a lake has formed within the basin, the water body is usually saline as a result of the internal drainage—the water has no outlet to the sea.

Eastern Anatolia Region

Eastern Anatolia, where the Pontic and Anti-Taurus mountain ranges converge, is rugged country with higher elevations, a more severe climate, and greater precipitation than are found on the Anatolian Plateau. The western part of the Eastern Anatolia Region is known as the Anti-Taurus, where the average elevation of mountain peaks exceed 3,000 meters; while the eastern part of the region was historically known as the Armenian Highland and includes Mount Ararat, the highest point in Turkey at 5,137 meters. Many of the East Anatolian peaks apparently are recently extinct volcanoes, to judge from extensive green lava flows. Turkey's largest lake, Lake Van, is situated in the mountains at an elevation of 1,546 meters. The headwaters of three major rivers arise in the Anti-Taurus: the east-flowing Aras, which pours into the Caspian Sea; the south-flowing Euphrates; and the south-flowing Tigris, which eventually joins the Euphrates in Iraq before emptying into the Persian Gulf. Several small streams that empty into the Black Sea or landlocked Lake Van also originate in these mountains.

In addition to its rugged mountains, the area is known for severe winters with heavy snowfalls. The few valleys and plains in these mountains tend to be fertile and to support diverse agriculture. The main basin is the Muş Valley, west of Lake Van. Narrow valleys also lie at the foot of the lofty peaks along river corridors.

Southeastern Anatolia Region

Southeast Anatolia is south of the Anti-Taurus Mountains. It is a region of rolling hills and a broad plateau surface that extends into Syria. Elevations decrease gradually, from about 800 meters in the north to about 500 meters in the south. Traditionally, wheat and barley were the main crops of the region, but the inauguration of major new irrigation projects in the 1980s has led to greater agricultural diversity and development.

Geology

Turkey's varied landscapes are the product of a wide variety of tectonic processes that have shaped Anatolia over millions of years and continue today as evidenced by frequent earthquakes and occasional volcanic eruptions. Except for a relatively small portion of its territory along the Syrian border that is a continuation of the Arabian Platform, Turkey geologically is part of the great Alpide belt that extends from the Atlantic Ocean to the Himalaya Mountains. This belt was formed during the Paleogene Period, as the Arabian, African, and Indian continental plates began to collide with the Eurasian plate. This process is still at work today as the African Plate converges with the Eurasian Plate and the Anatolian Plate escapes towards the west and southwest along strike-slip faults. These are the North Anatolian Fault Zone, which forms the present day plate boundary of Eurasia near the Black Sea coast, and the East Anatolian Fault Zone, which forms part of the boundary of the North Arabian Plate in the southeast. As a result, Turkey lies on one of the world's seismically most active regions.

However, many of the rocks exposed in Turkey were formed long before this process began. Turkey contains outcrops of Precambrian rocks, (more than 520 million years old; Bozkurt et al., 2000). The earliest geological history of Turkey is poorly understood, partly because of the problem of reconstructing how the region has been tectonically assembled by plate motions. Turkey can be thought of as a collage of different pieces (possibly terranes) of ancient continental and oceanic lithosphere stuck together by younger igneous, volcanic and sedimentary rocks.

During the Mesozoic era (about 250 to 66 million years ago) a large ocean (Tethys Ocean), floored by oceanic lithosphere existed in-between the supercontinents of Gondwana and Laurasia (which lay to the south and north respectively; Robertson & Dixon, 2006). This large oceanic plate was consumed at subduction zones (see subduction zone). At the subduction trenches the sedimentary rock layers that were deposited within the prehistoric Tethys Ocean buckled, were folded, faulted and tectonically mixed with huge blocks of crystalline basement rocks of the oceanic lithosphere. These blocks form a very complex mixture or mélange of rocks that include mainly serpentinite, basalt, dolerite and chert (e.g. Bergougnan, 1975). The Eurasian margin, now preserved in the Pontides (the Pontic Mountains along the Black Sea coast), is thought to have been geologically similar to the Western Pacific region today (e.g. Rice et al., 2006). Volcanic arcs (see volcanic arc) and backarc basins (see back-arc basin) formed and were emplaced onto Eurasia as ophiolites (see ophiolite) as they collided with microcontinents (literally relatively small plates of continental lithosphere; e.g. Ustaomer and Robertson, 1997). These microcontinents had been pulled away from the Gondwanan continent further south. Turkey is therefore made up from several different prehistorical microcontinents.

During the Cenozoic folding, faulting and uplifting, accompanied by volcanic activity and intrusion of igneous rocks was related to major continental collision between the larger Arabian and Eurasian plates (e.g. Robertson & Dixon, 1984).

Present-day earthquakes range from barely perceptible tremors to major movements measuring five or higher on the open-ended Richter scale. Turkey's most severe earthquake in the twentieth century occurred in Erzincan on the night of December 28–29, 1939; it devastated most of the city and caused an estimated 160,000 deaths. Earthquakes of moderate intensity often continue with sporadic aftershocks over periods of several days or even weeks. The most earthquake-prone part of Turkey is an arc-shaped region stretching from the general vicinity of Kocaeli to the area north of Lake Van on the border with Armenia and Georgia.

Turkey's terrain is structurally complex. A central massif composed of uplifted blocks and downfolded troughs, covered by recent deposits and giving the appearance of a plateau with rough terrain, is wedged between two folded mountain ranges that converge in the east. True lowlands are confined to the Ergene Ovası (Ergene Plain) in Thrace, extending along rivers that discharge into the Aegean Sea or the Sea of Marmara, and to a few narrow coastal strips along the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea coasts.

Nearly 85% of the land is at an elevation of at least 450 meters; the average and median altitude of the country is 1,332 and 1,128 meters, respectively. In Asiatic Turkey, flat or gently sloping land is rare and largely confined to the deltas of the Kızıl River, the coastal plains of Antalya and Adana, and the valley floors of the Gediz River and the Büyükmenderes River, and some interior high plains in Anatolia, mainly around Tuz Gölü (Salt Lake) and Konya Ovası (Konya Plain). Moderately sloping terrain is limited almost entirely outside Thrace to the hills of the Arabian Platform along the border with Syria.

More than 80% of the land surface is rough, broken, and mountainous, and therefore is of limited agricultural value (see Agriculture, ch. 3). The terrain's ruggedness is accentuated in the eastern part of the country, where the two mountain ranges converge into a lofty region with a median elevation of more than 1,500 meters, which reaches its highest point along the borders with Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran. Turkey's highest peak, Mount Ararat (Ağrı Dağı) — 5,137 meters high — is situated near the point where the boundaries of the four countries meet.

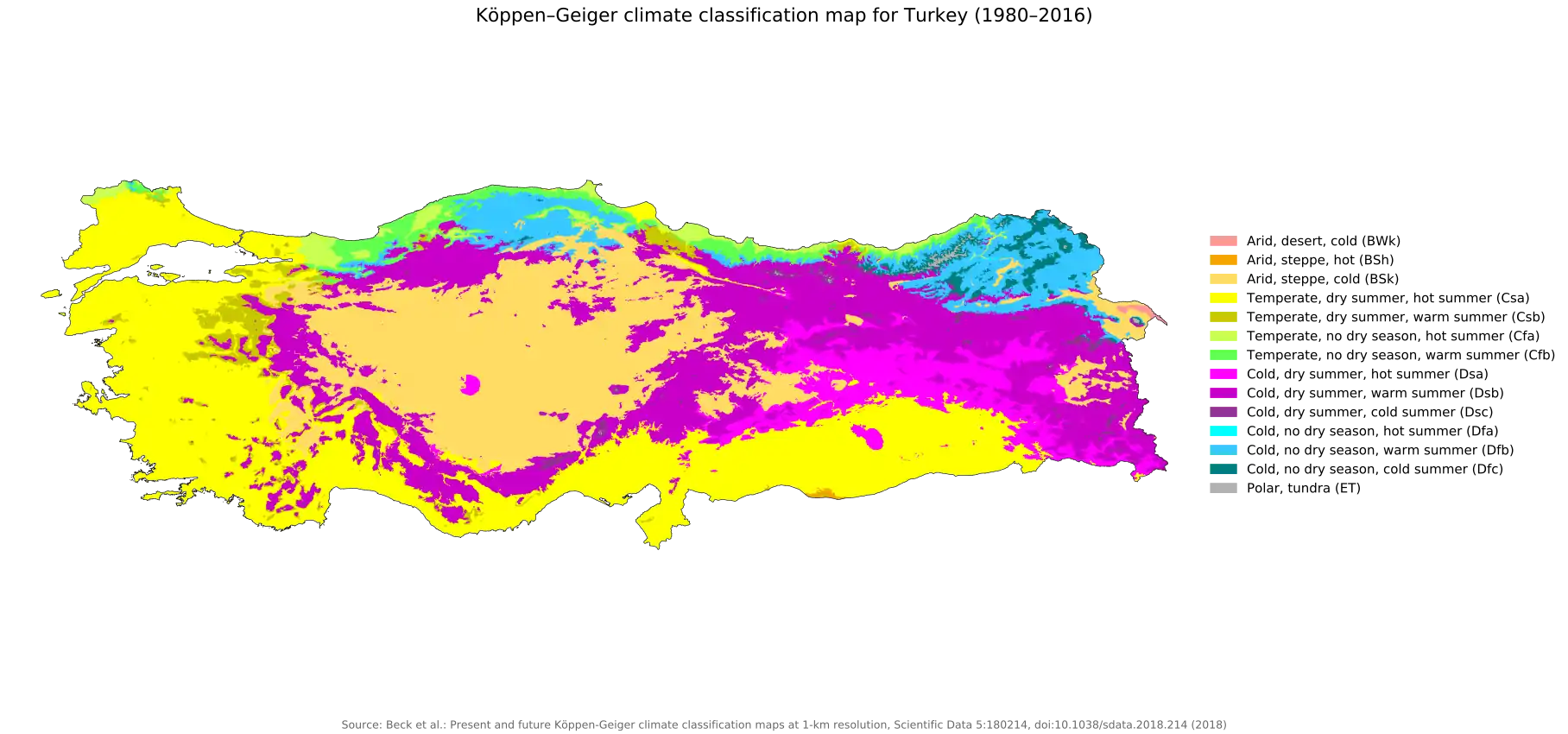

Climate

Turkey's diverse regions have different climates, with the weather system on the coasts contrasting with that prevailing in the interior. The Aegean and Mediterranean coasts have cool, rainy winters and hot, moderately dry summers. Annual precipitation in those areas varies from 580 to 1,300 millimeters (22.8 to 51.2 in), depending on location. Generally, rainfall is less to the east. The Black Sea coast receives the greatest amount of precipitation and is the only region of Turkey that receives high precipitation throughout the year. The eastern part of that coast averages 2,500 millimeters (98.4 in) annually which is the highest precipitation in the country.

Ankara

Ankara Antalya

Antalya Istanbul

Istanbul Van

Van

Mountains close to the coast prevent Mediterranean influences from extending inland, giving the interior of Turkey a continental climate with distinct seasons. The Anatolian Plateau is much more subject to extremes than are the coastal areas. Winters on the plateau are especially severe. Temperatures of −30 to −40 °C (−22 to −40 °F) can occur in the mountainous areas in the east, and snow may lie on the ground 120 days of the year. In the west, winter temperatures average below 1 °C (33.8 °F). Summers are hot and dry, with temperatures above 30 °C (86 °F). Annual precipitation averages about 400 millimeters (15.7 in), with actual amounts determined by elevation. The driest regions are the Konya Ovasi and the Malatya Ovasi, where annual rainfall frequently is less than 300 millimeters (11.8 in). May is generally the wettest month and July and August the driest.

The climate of the Anti-Taurus Mountain region of eastern Turkey can be inhospitable. Summers tend to be hot and extremely dry. Winters are bitterly cold with frequent, heavy snowfall. Villages can be isolated for several days during winter storms. Spring and autumn are generally mild, but during both seasons sudden hot and cold spells frequently occur.

| Regions | Average Temp. | Record High Temp. | Record Low Temp. | Average Hum. | Average Prec. | ||||

| Marmara Region | 13.5C | 56.3F | 44.6°C | 112.3°F | -27.8°C | -18.0°F | 71.2% | 564.3 mm | 22.2 in |

| Aegean Region | 15.4°C | 59.7°F | 48.5°C | 119.3°F | -45.6°C | -50.1°F | 60.9% | 706.0 mm | 27.8 in |

| Mediterranean Region | 16.4°C | 61.5°F | 45.6°C | 114.1°F | -33.5°C | -28.3°F | 63.9% | 706.0 mm | 27.8 in |

| Black Sea Region | 12.3°C | 54.1°F | 44.2°C | 111.6°F | -32.8°C | -27.0°F | 70.9% | 828.5 mm | 32.6 in |

| Central Anatolia | 10.6°C | 51.1°F | 41.8°C | 107.2°F | -36.2°C | -33.2°F | 62.6% | 392.0 mm | 15.4 in |

| East Anatolia | 9.7°C | 49.5°F | 44.4°C | 111.9°F | -45.6°C | -50.1°F | 60.9% | 569.0 mm | 22.4 in |

| Southeast Anatolia | 16.5°C | 61.7°F | 48.4°C | 119.1°F | -24.3°C | -11.7°F | 53.4% | 584.5 mm | 23.0 in |

Land use

Land use:

arable land:

35.00

permanent crops:

4.00

other:

61.00(2011)

Irrigated land: 53,400 km2 (2012)

Total renewable water resources: 211.6 km2 (2012)

Elevation extremes:

lowest point:

Mediterranean Sea 0 m

highest point:

Mount Ararat 5,166 m

Natural hazards

Very severe earthquakes, especially on the North Anatolian Fault and East Anatolian Fault, occur along an arc extending from the Sea of Marmara in the west to Lake Van in the east. On August 17, 1999, a 7.4-magnitude earthquake struck northwestern Turkey, killing more than 17,000 and injuring 44,000.

Map of earthquakes in Turkey 1900–2017 |

|

Environment

Category:Environment of Turkey

Current issues

Water pollution from dumping of chemicals and detergents; air pollution, particularly in urban areas; deforestation; concern for oil spills from increasing Bosphorus ship traffic.

Ratified international agreements

Air Pollution, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Wetlands.

Signed but unratified international agreements

Environmental Modification, Kigali Amendment, Paris Agreement

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Geography of Turkey. |

Notes

- https://www.medqsr.org/mediterranean-marine-and-coastal-environment

- http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/793?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10

- http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/966?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10

- http://www.seaaroundus.org/data/#/eez/794?chart=catch-chart&dimension=taxon&measure=tonnage&limit=10

- Sarıkaya, M. A. The Late Quaternary glaciation in the Eastern Mediterranean. In: Hughes P, Woodward J (eds) Quaternary glaciation in the Mediterranean mountains. Geological Society of London Special Publication 433, 2017, pp. 289–305.

- The Dorling Kindersley World Reference Atlas. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2014.

- The Dorling Kindersley World Reference Atlas. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2014.

- Erturaç, M. K. Kinematics and basin formation along the Ezinepazar-Sungurlu fault zone, NE Anatolia, Turkey. Turk J Earth Sci 21: 2012, pp. 497–520.

- Erturaç, M. K. Kinematics and basin formation along the Ezinepazar-Sungurlu fault zone, NE Anatolia, Turkey. Turk J Earth Sci 21: 2012, pp. 497–520.

- Finkel, Andrew, and Nukhet Sirman, eds. Turkish State, Turkish Society. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Finkel, Andrew, and Nukhet Sirman, eds. Turkish State, Turkish Society. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- Lewis, Geoffrey. Modern Turkey. New York: Praeger, 1974.

- Lewis, Geoffrey. Modern Turkey. New York: Praeger, 1974.

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. (2 vols.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Shaw, Stanford J., and Ezel Kural Shaw. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. (2 vols.) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- Finkel, Andrew, and Nukhet Sirman, eds. Turkish State, Turkish Society. New York: Routledge, 1990.

- "Worldofturkey.com: Regions of Turkey". Archived from the original on 2006-03-20. Retrieved 2006-03-27.

- Delaney, Carol. The Seed and the Soil of Turkey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Akçar, N. Paleoglaciations in Anatolia: A schematic review and first results. Eiszeitalt Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften 55: 2005, pp. 102–121.

- Erinç, S. Glacial evidences of the climatic variations in Turkey. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 34: 1952, pp. 89–98.

- Akçar, N. Paleoglaciations in Anatolia: A schematic review and first results. Eiszeitalt Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften 55: 2005, pp. 102–121.

- Birman, J. H. Glacial reconnaissance in Turkey. Geological Society of America Bulletin 79: 1968, pp. 1009–1026.

- Fleischer, R. The rock-tombs of the Pontic Kings in Amaseia (Amasya). In: Højte JM (ed) Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Black Sea Studies, vol 9. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, 2009, pp. 109–120.

- Fleischer, R. The rock-tombs of the Pontic Kings in Amaseia (Amasya). In: Højte JM (ed) Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Black Sea Studies, vol 9. Aarhus University Press, Aarhus, 2009, pp. 109–120.

- Akçar, N. Paleoglaciations in Anatolia: A schematic review and first results. Eiszeitalt Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften 55: 2005, pp. 102–121.

- Delaney, Carol. The Seed and the Soil of Turkey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Tunçel, H. Doğu Karadeniz Dağlarında Yaylacılık. Fırat Üniversitesi Sos Bilim Derg (Elazığ) 14(2): 2004, pp. 49–66.

- Kurdoğlu, O. Doğal ve Kültürel Değerlerin Korunması Açısından Kaçkar Dağları Milli Parkı’nın Önemi ve Mevcut Çevresel Tehditler. D.K. Ormancılık Araştırma Müdürlüğü, Ormancılık Araştırma Dergisi 21, ve Çevre ve Orman Bakanlığı Yayını 231: 2004, pp. 134–150.

- Erturaç, M. K. Kinematics and basin formation along the Ezinepazar-Sungurlu fault zone, NE Anatolia, Turkey. Turk J Earth Sci 21: 2012, pp. 497–520.

- Ekim, T. Türkiye Bitkileri Kırmızı Kitabı. 2000.

- Ekim, T. Türkiye Bitkileri Kırmızı Kitabı. 2000.

- Erturaç, M. K. Kinematics and basin formation along the Ezinepazar-Sungurlu fault zone, NE Anatolia, Turkey. Turk J Earth Sci 21: 2012, pp. 497–520.

- Brickell, Christopher. Encyclopedia of Plants and Flowers. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2011.

- Erturaç, M. K. Kinematics and basin formation along the Ezinepazar-Sungurlu fault zone, NE Anatolia, Turkey. Turk J Earth Sci 21: 2012, pp. 497–520.

- Delaney, Carol. The Seed and the Soil of Turkey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- Birman, J. H. Glacial reconnaissance in Turkey. Geological Society of America Bulletin 79: 1968, pp. 1009–1026.

- Delaney, Carol. The Seed and the Soil of Turkey. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

References

- Bergougnan, H. (1976) Dispositif des ophiolites nord-est anatoliennes, origine des nappes ophiolitiques et sud-pontiques, jeu de la faille nord-anatolienne. Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l'Académie des Sciences, Série D: Sciences Naturelles, 281: 107–110.

- Bozkurt, E. and Satir, M. (2000) The southern Menderes Massif (western Turkey); geochronology and exhumation history. Geological Journal, 35: 285–296.

- Rice, S.P., Robertson, A.H.F. and Ustaömer, T. (2006) Late Cretaceous-Early Cenozoic tectonic evolution of the Eurasian active margin in the Central and Eastern Pontides, northern Turkey. In: Robertson, (Editor), Tectonic Development of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 260, London, 413–445.

- Robertson, A. and Dixon, J.E.D. (1984) Introduction: aspects of the geological evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean. In: Dixon and Robertson (Editors), The Geological Evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 17, 1–74.

- Ustaömer, T. and Robertson, A. (1997) Tectonic-sedimentary evolution of the north Tethyan margin in the Central Pontides of northern Turkey. In: A.G. Robinson (Editor), Regional and Petroleum Geology of the Black Sea and Surrounding Region. AAPG Memoir, 68, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 255–290.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress Country Studies website http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/. This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the CIA World Factbook website https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/.