Kathashruti Upanishad

The Kathashruti Upanishad (Sanskrit: कठश्रुति उपनिषत्, IAST: Kaṭhaśruti Upaniṣad) is a minor Upanishad of Hinduism.[4] The Sanskrit text is one of the 20 Sannyasa Upanishads,[5] and is attached to the Krishna Yajurveda.[6]

| Kathashruti Upanishad | |

|---|---|

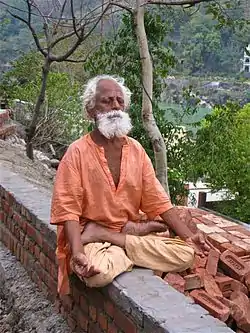

The Kathashruti Upanishad discusses rites of passage for a Sannyasi | |

| Devanagari | कठश्रुति |

| IAST | Kaṭhaśruti |

| Title means | Named after Vedic school[1] |

| Date | before 300 CE, likely BCE[2] |

| Type | Sannyasa |

| Linked Veda | Yajurveda |

| Chapters | 1 |

| Verses | 42[3] |

| Philosophy | Vedanta |

This ancient text on renunciation describes the lifestyle of Hindu monks.[7][8] A Sannyasi, states the text, should contemplate on soul, lead a simple life without any possession, be chaste and compassionate to all living beings, neither rejoice when someone praises him, nor curse when someone abuses him.[9][10]

History

The century in which Kathashruti Upanishad was composed, like most ancient Indian texts, is unclear.[2] Textual references and literary style suggest that this Hindu text is ancient, probably in the centuries around the start of the common era.[2] This text was likely composed before the Asrama Upanishad which itself is dated to the 3rd-century CE.[2] The Kathashruti Upanishad, states Sprockhoff, is quite similar in sections to the more ancient Vedic text Manava-Shrauta Sutra, which means the Upanishad had a prehistory and was likely a compilation of traditions that existed in the earlier centuries of the 1st millennium BCE.[11] Gavin Flood dates the Sannyasa Upanishads like Kathashruti to the first few centuries of the common era.[12]

Its Sanskrit manuscript was translated by Ramanathan in 1978, but this translation has been reviewed as "extremely poor and inaccurate".[13] Two additional translations were published by Sprockoff in 1990,[14] and by Olivelle in 1992.[3]

This text has been sometimes titled as Kanthashruti Upanishad in some discovered manuscripts,[15] and in southern[16] Indian manuscript versions as Katharudra Upanishad.[17][18] According to Max Muller, Kanthashruti Upanishad has been supposed as a misnomer for Kathasruti.[19] In the Telugu language anthology of 108 Upanishads of the Muktika canon, narrated by Rama to Hanuman, it is listed at number 83.[4]In the Colebrooke's version of 52 Upanishads, popular in north India, it is listed at number 26 [20] The Narayana anthology also includes this Upanishad at number 26 in Bibliothica Indica.[21]

Content

He should recite the mantras regarding the self,

And say, "May all living beings prosper!"

Wear brownish red garment,

Stop shaving armpits and pubic region,

Shave his head and face, wear no string,

And use his stomach as a begging bowl,

wander about homeless,

carry a water strainer to protect living things,

Sleep on river bank or in a temple.

The text presents the theme of renunciation as well as a description of the life of someone who has chosen the monastic path of life as a sannyasi in Hindu Ashrama culture.[7][24][25] The Upanishad opens by stating that the renouncer, after following the prescribed order, and performing prescribed rites becomes a renunciant, should obtain the cheerful approval of his mother, father, wife, other family members and relatives, then distribute his property in any way he wishes, cut off his topknot hair and discard all possessions, before leaving them forever.[26] As he is leaving, the sannyasi thinks of himself, "you are the Brahman (ultimate reality), you are the sacrifice, you are the universe".[27]

The sannyasi should, states the text, contemplate on Atman (soul, self), pursue knowledge, lead a simple life without any possession, be chaste and compassionate to all living beings, neither rejoice when someone praises him, nor curse when someone abuses him.[22][28] The Hindu monk, according to Kathashruti, states Dhavamony, is not tied to any locality, he is enjoined to silence, meditation and Yoga practice.[29] Renunciation in Hindu texts such as this Upanishad, adds Dhavamony, is more than physical and social renunciation, it includes inner renunciation of "anger, desire, deceit, pride, envy, infatuation, falsehood, greed, pleasure, pain and similar states of existence".[29]

The text is notable for asserting a view that was opposite to that of Jabala Upanishad, on "who can appropriately renounce".[30] The Kathashruti Upanishad asserts, in verses 31–38, that the four stages of life be sequential, that a man should first get the student should get educated in Vedas and thereafter he should marry, raise a family in household, settle his children in life, retire, and then renounce after getting the consent of his wife, family and elders at one place.[31] In contrast, the Jabala Upanishad, another ancient Hindu text of the same era, first acknowledges the sequential steps, but thereafter asserts the view that anyone in any stage of life can renounce, whether he is married or unmarried, immediately after education or at a time of his choice, if he feels detached from the world.[32] Jabala Upanishad recommends pre-informing and persuading one's elders, family members and neighbors, but leaves the ultimate choice to the one who wants to renounce and lead a wandering monastic life.[31][32]

References

- Deussen 1997, p. 745.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 5, 8–9.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 129–136.

- Deussen 1997, pp. 556–557.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. x–xi, 5.

- Tinoco 1996, p. 89.

- Freiberger 2005, p. 236 with footnote 4.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 134–136.

- Olivelle 1992, p. 136, Quote: "When he is praised let him not rejoice, nor curse others when he is reviled"..

- Deussen 1997, p. 751, Quote: "Not rejoicing, when praised; Not cursing those who abuse him. (...)".

- Joachim Sprockhoff (1987), Kathasruti und Manavasrautasutra – eine Nachlese zur Resignation, Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik, Vol. 13–14, pages 235–257

- Flood 1996, p. 91.

- Olivelle 1992, p. 7 with footnote 11.

- Joachim Sprockhoff (1990), Vom Umgag mit den Samnyasa Upanishads, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens, Vol. 34, pages 5–48 (in German)

- Deussen 1997, pp. 557, 745.

- Olivelle 1992, p. 8.

- Joachim Sprockhoff (1989), Versuch einer deutschen Ubersetzung der Kathasruti und der Katharudra Upanisad, Asiatische Studien, Vol. 43, pages 137–163 (in German)

- Yael Bentor (2000), Interiorized Fire Rituals in India and in Tibet, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 120, No. 4, page 602 with footnote 45

- Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. Steiner in Komm. 1865. pp. 141–.

- Deussen 1997, p. 561.

- Deussen 1997, p. 562.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 135–136 with footnotes.

- Deussen 1997, p. 750.

- Olivelle 1992, p. 5.

- Schweitzer, Albert; Russell, Mrs. Charles E. B. (1936). "Indian Thoughts And Its Development". Rodder and Stougkton, archived by Archive Organization. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 129–130 with footnotes.

- Deussen 1997, p. 747.

- Deussen 1997, p. 748, 750–751.

- Dhavamony 2002, p. 97.

- Olivelle 1993, pp. 84–85, 118–119, 178–179.

- Olivelle 1992, pp. 84–85.

- Olivelle 1993, pp. 118–119, 178–179.

Bibliography

- Dhavamony, Mariasusai (2002). Hindu-Christian Dialogue: Theological Soundings and Perspectives. Rodopi. ISBN 978-9042015104.

- Deussen, Paul (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- Deussen, Paul (2010). The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Oxford University Press (Reprinted by Cosimo). ISBN 978-1-61640-239-6.

- Freiberger, Oliver (2005). Words and Deeds: Hindu and Buddhist Rituals in South Asia (Editors: Jörg Gengnagel, Ute Hüsken). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447051521.

- Farquhar, John Nicol (1920). An outline of the religious literature of India. H. Milford, Oxford University Press. ISBN 81-208-2086-X.

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521438780

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992). The Samnyasa Upanisads. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195070453.

- Olivelle, Patrick (1993). The Asrama System. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195083279.

- Tinoco, Carlos Alberto (1996). Upanishads. IBRASA. ISBN 978-85-348-0040-2.