Tejobindu Upanishad

The Tejobindu Upanishad (Sanskrit: तेजोबिन्दु उपनिषद्) is a minor Upanishad in the corpus of Upanishadic texts of Hinduism.[2] It is one of the five Bindu Upanishads, all attached to the Atharvaveda,[3] and one of twenty Yoga Upanishads in the four Vedas.[4][5]

| Tejobindu Upanishad | |

|---|---|

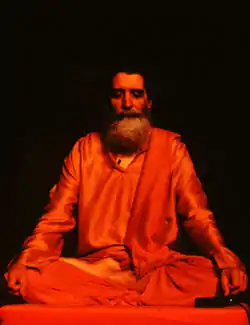

Tejobindu states meditation is difficult but empowering | |

| Devanagari | तेजोबिन्दु |

| Title means | Radiant power of point |

| Date | 100 BCE to 300 CE[1] |

| Linked Veda | Yajurveda or Atharvaveda |

| Verses | Varies by manuscript |

| Philosophy | Yoga, Vedanta |

The text is notable for its focus on meditation, calling dedication to bookish learning as rubbish, emphasizing practice instead, and presenting the Vedanta doctrine from Yoga perspective.[6]

The Tejobindu is listed at number 37 in the serial order of the Muktika enumerated by Rama to Hanuman in the modern era anthology of 108 Upanishads.[7]

Nomenclature

Tejobindu, states Paul Deussen, means "the point representing the power of Brahman", wherein the point is the Anusvara in Om.[8]

The Tejobindu Upanishad is sometimes spelled as Tejabindu Upanishad (Sanskrit: तेजबिन्दु), such as in the Poona manuscript versions.[9]

Chronology and anthology

Mircea Eliade suggests that Tejobindu Upanishad was possibly composed in the same period as the didactic parts of the Mahabharata, the chief Sannyasa Upanishads and along with other early Yoga Upanishads: Brahmabindu (probably composed about the same time as Maitri Upanishad), Ksurika, Amritabindu, Brahmavidya, Nadabindu, Yogashikha, Dhyanabindu and Yogatattva.[10] Eliade's suggestion places these in the final centuries of BCE or early centuries of the CE. All these, adds Eliade, were likely composed earlier than the ten or eleven later Yoga Upanishads such as the Yoga-kundalini, Varaha and Pashupatabrahma Upanishads.[10]

Gavin Flood dates the Tejobindu text, along with other Yoga Upanishads, to be probably from the 100 BCE to 300 CE period.[1]

This Upanishad is among those which have been differently attached to two Vedas, depending on the region where the manuscript was found. Deussen states, it and all Bindu Upanishads are attached to the Atharvaveda,[3] while Ayyangar states it is attached to the Krishna Yajurveda.[11][12]

Colebrooke's version of 52 Upanishads, popular in north India, lists this Upanishad's text at number 21 along with the other four Bindu Upanishads with similar theme.[13] The Narayana anthology also includes this Upanishad at number 21 in Bibliothica Indica.[14] In the collection of Upanishads under the title "Oupanekhat", put together by Sultan Mohammed Dara Shikhoh in 1656, consisting of a Persian translation of 50 Upanishads and who prefaced it as the best book on religion, the Tejobindu is listed at number 27 and is named Tidj bandeh.[15]

Structure

This text is part of the five Bindu Upanishads collection, the longest among the five, the other four being the Nadabindu Upanishad, the Brahmabindu Upanishad, the Amritabindu Upanishad and the Dhyanabindu Upanishad, all forming part of the Atharvaveda. All five of Bindu Upanishads emphasize the practice of Yoga and Dhyana (meditation) with Om, to apprehend Atman (soul, self).[16]

Like almost all other Yoga Upanishads, the text is composed in poetic verse form.[17]

The text exists in multiple versions. The manuscript translated by Deussen is short. It has fourteen verses, describing how difficult meditation is in its first two verses, the requirements for a successful meditative practice in next two, the need for the universal constant Brahman as the radiant focal point of meditation and the nature of Brahman in verses 5 to 11, then closes the text by describing the Yogi who has achieved the state of "liberation, freedom" (moksha) while being alive.[6]

The manuscript translated by TRS Ayyangar of Adyar Library is long, and has six chapters with a cumulative total of 465 verses.[18] The first chapter contains 51 verses, the second has 43 verses, the third with 74 verses, the fourth contains 81 verses, fifth has 105, and the last sixth chapter has 111 verses.[18] Two chapters, in the longer version, are structured as a discourse, with chapters 2 to 4 between Kumara and his father Shiva, and the last two chapters between Nidagha and Ribhu.[19][18] Deussen states that the shorter form may be a trimmed, "enormously corrupt text transmission".[8]

Contents

Meditation is difficult

The text opens by asserting that Dhyana (meditation) is difficult, and increasingly so as one proceeds from gross, then fine, then superfine states.[8] Even the wise and those who are alone, states the text, find meditation difficult to establish, implement and accomplish.[21]

दुःसाध्यं च दुराराध्यं दुष्प्रेक्ष्यं च दुराश्रयम् |

दुर्लक्षं दुस्तरं ध्यानं मुनीनां च मनीषिणाम् ||२||

"Even to the wise and the thoughtful this meditation is difficult to perform, and difficult to attain,

difficult to cognise and difficult to abide in, difficult to define and difficult to cross."

How to meditate successfully?

For success in Dhyana, asserts the text, one must first conquer anger, greed, lust, attachments, expectations, worries about wife and children.[21][24] Give up sloth and lead a virtuous life.[25] Be temperate in the food you eat, states Tejobindu, abandon your delusions, and crave not.[26] Find a Guru, respect him and strive to learn from him, states the text.[21]

The fifteen limb yoga

Yamas is restraining organs of perception and action, in and through knowledge.

— Tejobindu Upanishad 1.17[27]

The Tejobindu Upanishad begins its discussion of Yoga, with a list of fifteen Angas (limbs), as follows: Yamas (self control), Niyama (right observances), Tyaga (renunciation), Mauna (silence, inner quietness), Desa (right place, seclusion), Kala (right time), Asana (correct posture), Mula-bandha (yogic root-lock technique), Dehasamyama (body equilibrium, no quivering), Drksthiti (mind equilibrium, stable introspection), Pranasamyama (breath equilibrium), Pratyahara (withdrawal of senses), Dharana (concentration), Atma-dhyana (meditation on Universal Self), Samadhi (identification with individual self is dropped).[28][29]

The Tejobindu briefly defines these fifteen limbs in verses 1.17 to 1.37, without details. The verses 1.38 to 1.51 describe the difficulty in achieving meditation and Samadhi, and ways to overcome these difficulties.[30][31] One must function in the world and be good at what one does, improve upon it, yet avoid longing, state verses 1.44–1.45. Physical yoga alone does not provide the full results, unless introspection and right knowledge purifies the mind, state verses 1.48–1.49 of the longer manuscript.[30] One must abandon anger, selfish bonds to things and people, likes and dislikes to achieve Samadhi, states verse 3 of the shorter version of the manuscript.[24]

The indivisible oneness in the essence of all

Chapter 2 is a discourse from Shiva to his son Kumara on "Individual One Essence". This is Atman (soul, self), states Shiva, it is all existence, the entire world, all knowledge, all space, all time, all Vedas, all introspection, all preceptors, all bodies, all minds, all learning, all that is little, all that is big, and it is Brahman.[32][33] "Individual One Essence" is identical to but called by many names such as Hari and Rudra, and it is without origin, it is gross, subtle and vast in form. "Individual One Essence" is thou, a mystery, that which is permanent, and that which is the knower.[32] It is the father, it is the mother, it is the sutra, it is the Vira, what is within, what is without, the nectar, the home, the sun, the crop field, the tranquility, the patience, the good quality, the Om, the radiance, the true wealth, the Atman.[32][33]

Shiva describes the nature of consciousness in verses 2.24–2.41, and asserts the Vedanta doctrine, "Atman is identical with Brahman" in the final verses of chapter 2.[34][35]

Atman and Brahman

The Tejabindu Upanishad, states Madhavananda, conceives the Supreme Atman as dwelling in the heart of man, as the most subtle centre of effulgence, revealed to yogis by super-sensuous meditation.[22] This Atman and its identity with Brahman, that where the saying Tat Tvam Asi refers to, is the subject of chapter 3. It is that which is to be meditated upon, and realised in essence, for the absolute freedom of the soul, and for the realization of the True Self.[22][23]

The text mentions Shiva explaining the non-dual (Advaita) nature of Atman and Brahman.[36] The verses describe the Atman to be bliss, peace, contentment, consciousness, delight, satisfaction, absolute, imperishable, radiant, Nirguna (without attributes or qualities), without beginning, without end, and repeatedly states "I am Atman", "I am Brahman" and "I am the Indivisible One Essence".[37][38] The Upanishad also states that the ultimate reality (Brahman) is also called Vishnu, it is consciousness as such.[39] This discussion in Tejobindu Upanishad, a Yoga Upanishad, is entirely compatible with the discussions in the major Vedanta Upanishads.[39]

In the shorter manuscript version, translates Eknath Easwaran, "the Brahman gives himself through his infinite grace to ones who abandon the viewpoint of duality".[40]

Jivanmukti and Videhamukti

The chapter 4 of the Upanishad, in a discourse from Shiva to his son Kumara, describes Jivanmukta as follows (abridged):

He is known as a Jivan-mukta who stands alone in Atman, who realizes he is transcendent and beyond the concept of transcendence, who understands, "I am pure consciousness, I am Brahman". He knows and feels that there is one Brahman, who is full of exquisite bliss, and that he is He, he is Brahman, he is that bliss of Brahman. His mind is clear, he is devoid of worries, he is beyond egoism, beyond lust, beyond anger, beyond blemish, beyond symbols, beyond his changing body, beyond bondage, beyond reincarnation, beyond precept, beyond religious merit, beyond sin, beyond dualism, beyond the three worlds, beyond nearness, beyond distance. He is the one who realizes, "I am Brahman, I am pure Consciousness; Pure Consciousness is what I am".

The text asserts that a Jivanmukta has Self-knowledge, knows that his Self (Atman) is pure as a Hamsa (Swan), he is firmly planted in himself, in the kingdom of his soul, peaceful, comfortable, kind, happy, living by his own accord.[41][44] He is "the Lord of his own Self", state verses 4.31–4.32 of the text.[41][44]

The Tejobindu Upanishad, in verses 4.33–4.79 describes Videhamukta, and the difference between Videha mukti and Jivanmukti.[45]

A Videhamukta, states the text, is one who is beyond the witnessing state of awareness. [46] He is beyond the "all is Brahman" conviction. He sees all in his Atman, but does not have the conviction that I am Brahman.[46] A Videhamukta accepts the other world, and has no fear of the other world.[47] He who does not conceive of "Thou Art That", "this Atman is Brahman", yet is the Atman that never decays. He is consciousness, devoid of light and non-light, blissful. He is Videhamukta, states verses 4.68–4.79 of the text.[48][49]

Atman versus Anatman

The fifth chapter of the text presents the theory of Atman and of Anatman, as a discourse between Muni Nidagha and the Vedic sage Ribhu.[50]

Atman is imperishable, states Ribhu, full of bliss, transcendental, bright, luminous, eternal, identical to Brahman and it is Brahman alone.[51][52] The Buddhist concept of "Anatman" (not-self) is a false concept, asserts Ribhu, and there is no such thing as Anatman by reason that it contradicts the existence of free will.[53][54] The Anatman concept that assumes absence of consciousness is flawed because if consciousness is nonexistent then nothing could be conceived, just like no destination could be reached in the absence of feet, and no work can be done in the absence of hands or no death can happen in the absence of birth, states the text in verses 5.16 to 5.21.[53][54] Anatman is a false notion, asserts the text, as it implies that ethics etc. has no basis to it.

The verses in chapter 5 repeat the ideas of the previous chapters.[55] It adds in verses 5.89–5.97 that the idea, "I am my body" is false and the definition of self as body is the reason for bondage. It is a false impression created by mind: Then the text asserts again the truth that the Unchanging is the Atman.[56] It is also stated that this chapter is probably a later addition to the original version of the Upanishad.[55]

The nature of Satcitananda

The last chapter continues the discourse attributed to Muni Nidagha and the Vedic age Ribhu. Everything is of the nature of Sat-Chit-Ananda, existence-consciousness-bliss, asserts Ribhu. Sat-Chit-Ananda is the imperishable essence of all and everything.[57] In a certain sense there is, translates TRS Ayyangar of Adyar Library, no such thing as "thou", nor "I" nor "other", and all is essentially the absolute Brahman.[57] In the deepest analysis there are no scriptures, no beginning, no end, no misery, no happiness, no illusions, no such thing as arising out of gods, nor evil spirits, nor five elements, no permanence, no transience, no worship, no prayer, no oblation, no mantra, no thief, no kindness, nothing is really Real except existence-consciousness-bliss.[58]

Ultimately all is Brahman alone.[59] Ribu asserts: Time is Brahman, Art is Brahman, happiness is Brahman, Self-luminousity is Brahman, Brahman is fascination, tranquility, virtue, auspiciousness, inauspiciousness, purity, impurity, all the world is the manifestation of the One Brahman.[59] Brahman is the Self of all, (Atman), there is no world other than that made of Brahman.[60] Know thyself as a form of Brahman.[60]

The one who is liberated, knows himself to be sat-chit-ananda

Renouncing greed, delusion, fear, pride, anger, love, sin,

Renouncing the pride of the Brahmin descent, and all the rubbish liberation texts,

Knowing no fear, nor lust, nor pain, nor respect, nor disrespect any more,

Because Brahman is free from all these things, the highest goal of all endeavor.

Reception

The Tejobindu Upanishad, states Laurence Rosan, Professor and Departmental Representative in University of Chicago, is a classic in the history of absolute subjective idealism.[62] The Neoplatonism of Proclus, though not identical, parallels the monistic idealism found in Tejobindu Upanishad.[63] The 5th-century CE philosopher Proclus of Greece proposed organic unity of all levels of reality, the integrative immanence of One Reality, and universal love.[64] These ideas independently appear, states Rosan, in Tejobindu Upanishad as well, in the most fully developed, longest litany of singular consciousness.[65]

While the conceptual foundations of Tejobindu are found in ancient major Upanishads such as the Chandogya (~800–600 BCE) and many minor Upanishads such as Atmabodha, Maitreyi and Subala, it is Tejobindu that dwells on the idea extensively, states Rosan, with the phrases Akhanda-eka-rasa (Undivided One Essence) and Chit-matra (Consciousness as such).[66] The absolute idealism doctrine in Tejobindu is closely related to the Neoplatonic doctrine of Proclus.[67]

The Tejobindu stands as a wonderful monument in the history of subjective monistic idealism, the Tejobindu is a victorious, fully accomplished statement.

— Laurence Rosan, Proclus and the Tejobindu Upanisad[68]

It is also said that the nondualism concept in Tejobindu is philosophic, it is metaphysics and cannot be reduced to phenomenology.[69]

The text has also been important to the historical study of Indian yoga traditions. Klaus Klostermaier, for example, states that Tejobindu Upanishad is a fairly detailed Hindu treatise on Raja Yoga.[70]

Notes

- Eknath Easwaran translates these verses differently, as follows:

Brahman cannot be realized by those,

who are subject to greed, fear, and anger.

Brahman cannot be realized by those,

who are subject to the pride of name and fame,

Or to the vanity of scholarship.

Brahman cannot be realized by those,

who are enmeshed in life's duality.

But to all those who pierce this duality,

Brahman gives himself through his infinite grace.[40]

References

- Flood 1996, p. 96.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 557, 713.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 567.

- Ayyangar 1938, p. vii.

- G. M. Patil (1978), Ishvara in Yoga philosophy, The Brahmavadin, Volume 13, Vivekananda Prakashan Kendra, pages 209–210

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 705–707.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 556.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 705.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 705 with footnote 1.

- Mircea Eliade (1970), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691017646, pages 128–129

- Ayyangar 1938, p. 27.

- Alain Danielou (1991), Yoga: Mastering the Secrets of Matter and the Universe, Inner Traditions, ISBN 978-0892813018, page 168

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule 1997, p. 561.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule 1997, p. 562.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, pp. 558–59.

- Deussen 2010, p. 9.

- Deussen 2010, p. 26.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 27–87.

- Larson & Potter 1970, p. 596.

- Deussen 2010, p. 390.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 706.

- Swami Madhavananda. Minor Upanishads. Advaita Ashrama. p. 28.

- Swami Parmeshwaranand (2000). Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanishads, Vol.3. Sarup & Sons. pp. 779–794. ISBN 9788176251488.

- Easwaran 2010, p. 228.

- Ayyangar 1938, p. 28.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 28–30.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 30–31.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 30–33.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 1.15–1.16.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 33–36.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 1.38–1.51.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 36–39.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 2.1–2.23.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 40–41.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 2.24–2.43.

- Swami Madhavananda. Minor Upanishads. Advaita Ashrama. pp. 28–33.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 41–46.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 3.1–3.43.

- Larson & Potter 1970, pp. 596–597.

- Easwaran 2010, p. 229.

- Ayyangar 1938, p. 54.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 4.1–4.30.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 50–54.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 4.31–4.32.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 54–60.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 54–55.

- Ayyangar 1938, p. 56.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 59–60.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 4.68–4.79.

- Ayyangar 1938, p. 61.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 61–62.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 5.1–5.15.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 63–64.

- Hattangadi 2015, pp. verses 5.16–5.21.

- Larson & Potter 1970, p. 597.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 71–74.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 74–75.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 75–77.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 77–78.

- Ayyangar 1938, pp. 79–80.

- Deussen, Bedekar & Palsule (tr.) 1997, p. 707.

- Rosan 1981, p. 53.

- Rosan 1981, pp. 45–46, 60–61.

- Rosan 1981, pp. 45–50.

- Rosan 1981, pp. 52–53.

- Rosan 1981, pp. 54–56.

- Rosan 1981, p. 55.

- Rosan 1981, p. 61.

- Rosan 1981, p. 331.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (2000), Hindu Writings: A Short Introduction to the Major Sources, Oneworld, ISBN 978-1851682300, page 110

Bibliography

- Ayyangar, TR Srinivasa (1938). The Yoga Upanishads. The Adyar Library.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M.; Palsule, G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Derek (tr), Coltman (1989). Yoga and the Hindu Tradition. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0543-9.

- Deussen, Paul (2010). The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61640-239-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Deussen, Paul; Bedekar, V.M. (tr.); Palsule (tr.), G.B. (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Easwaran, Eknath (1 June 2010). The Upanishads: The Classics of Indian Spirituality (Large Print 16pt). ReadHowYouWant.com. ISBN 978-1-4587-7829-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521438780CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hattangadi, Sunder (2015). "तेजोबिन्दु (Tejobindu Upanishad)" (PDF) (in Sanskrit). Retrieved 12 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larson, Gerald James; Potter, Karl H. (1970). Tejobindu Upanishad (Translated by NSS Raman), in The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India's philosophy of meditation. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosan, Laurence (1981). Neoplatonism and Indian Thought (Editor: R Baine Harris). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0873955461.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Tejobindu Upanishad, Sunder Hattangadi (2015), in Sanskrit

- Tejobindu Upanishad, in English