Keilhauia

Keilhauia is a genus of ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaur, a type of dolphin-like, large-eyed marine reptile, from the Early Cretaceous shallow marine Slottsmøya Member of the Agardhfjellet Formation in Svalbard, Norway. The genus contains a single species, K. nui, known from a single specimen discovered in 2010 and described by Delsett et al. in 2017. In life, Keilhauia probably measured approximately 4 metres (13 ft) in length; it can be distinguished by other ophthalmosaurids by the wide top end of its ilium and the relatively short ischiopubis (the fusion of the ischium and the pubis) compared to the femur. Although it was placed in a basal position within the Ophthalmosauridae by phylogenetic analysis, this placement is probably incorrect.

| Keilhauia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Diagram of holotype specimen as preserved | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Family: | †Ophthalmosauridae |

| Genus: | †Keilhauia Delsett et al., 2017 |

| Species: | †K. nui |

| Binomial name | |

| †Keilhauia nui Delsett et al., 2017 | |

Description

Judging by the partially preserved holotype specimen, Keilhauia has been estimated at 3.8–4.3 metres (12–14 ft) based on comparisons to the related ophthalmosaurid Cryopterygius.[1][2] This specimen was probably mature or close to maturity at time of death, judging by the convex head of the humerus and the smooth texture of the humeral shaft.[1][3]

Skull and axial skeleton

Although only a small portion of the snout is known, it seems to be taller than that of Aegirosaurus,[4] instead being more similar to those of Cryopterygius[2] and Caypullisaurus.[5] A shallow groove that housed blood vessels, known as the nutrient foramen, is visible on the side of the jaw. About ten teeth are preserved; they are conical, narrow at the tip, and slightly curved.[1]

It is difficult to estimate the exact number of vertebral segments that were present in front of the sacrum; the preserved centra suggest that there are at least 43. This is more than the 42 in Athabascasaurus,[6] the 41 in Nannopterygius, and the 37 in Platypterygius americanus,[7] but less than the 46 in Platypterygius australis[8] and the 50 or more in Cryopterygius,[2] Aegirosaurus,[4] and Platypterygius platydactylus. The posterior dorsal vertebrae are wider and taller than those near the front, and their front and rear faces are rounded. The first few caudal vertebrae are the proportionally tallest and widest of all the vertebrae,[9] but the vertebrae quickly become shorter vertically prior to the bend in the tail that supported the tail fluke.[1]

Each neural spine is about the same length as the underlying centrum, which is similar to Cryopterygius[2] but not Ophthalmosaurus (in which they are proportionally longer in the posterior cervical vertebrae). Similar to Gengasaurus,[10] the first few neural spines are taller than the corresponding centra, but then decrease in height gradually. The tops of the neural spines, which are the thinnest parts of the bones, are straight, instead of being notched like Cryopterygius[2] or Platypterygius australis.[8] The ribs are shaped like a figure eight in cross section near their top ends, but this is less obvious closer to the bottom; such a morphology is typical among ophthalmosaurids, except for Acamptonectes[11] and Mollesaurus.[12] The dorsal ribs are around 75–81 cm (30–32 in) long, while the first few caudal ribs are only 2–5 cm (0.79–1.97 in) long.[1]

Forelimb and pectoral girdle

In Keilhauia, the scapula has a relatively straight blade that was broadened at its front end into a fan-like acromion process. This process is less prominent than that of Acamptonectes[11] and Sveltonectes,[13] instead being more similar to that of Cryopterygius,[2] Platypterygius hercynicus, and Sisteronia.[14] The scapula formed more of the glenoid than the coracoid; like Sveltonectes[13] but unlike Cryopterygius,[2] the glenoid does not extend onto the bottom face of the scapula. The de facto blade of the scapula was widest near the middle, and angled slightly downwards; like Acamptonectes[11] but unlike all other ophthalmosaurids, the blade has a relatively uniform thickness along its entire length.[1]

The clavicle, which is not fused to other elements in the pectoral girdle, bears a thickened process on its frontal bottom edge which points towards the midline of the torso. This process is relatively short, square-shaped from the front, and bordered by a rim on its back edge. In most other ophthalmosaurids, this same process is more finger-like, although some specimens of Ophthalmosaurus have similar processes. The back part of the clavicle gradually narrows into a curved point, as in Ophthalmosaurus, Baptanodon, and Janusaurus.[15][1]

The coracoid is a kidney-shaped bone that is about as long as it is wide, compared to Cryopterygius,[2] Nannopterygius, and Sveltonectes,[13] where it is not as wide proportionally. Like Ophthalmosaurus and Arthropterygius,[16] the coracoid bears a prominent notch on its front edge; it also bears a ridge on the frontal part of its midline, like Ophthalmosaurus and Acamptonectes,[11] but unlike Caypullisaurus[5] and Platypterygius australis.[8] Its articular facets with the scapula and glenoid are clearly separate, as in Sveltonectes[13] but not Acamptonectes.[11] The former is only about 45% of the latter in length; this figure is 50% in Cryopterygius,[2] and the two facets are effectively the same length in Janusaurus.[15][1]

There are two prominent processes on the humerus. The longer, less prominent, and more ridge-like of these is the dorsal process. This process is remarkably short compared to other ophthalmosaurids, being less than half of the length of the humeral shaft, a condition also seen in Undorosaurus and Aegirosaurus;[4] in Ophthalmosaurus, Brachypterygius, Paraophthalmosaurus, and Cryopterygius,[2] the process reaches the midpoint of the humerus, while it is even longer in Arthropterygius,[16] Platypterygius americanus,[7] Platypterygius australis,[8] and Platypterygius hercynicus.[17] The other process is the deltopectoral crest, which is similarly small among ophthalmosaurids (i.e. less than half of the shaft length) in the same manner as Arthropterygius,[16] Platypterygius hercynicus,[17] and Janusaurus;[15] it is about half of the shaft length in Ophthalmosaurus, and is almost as long as the entire shaft in Sisteronia,[14] Acamptonectes,[11] and Platypterygius americanus.[7][1]

At the midpoint of the humeral shaft, the bone is mildly constricted, being approximately 20% narrower than the maximum width. The bottom end of the humerus is larger than the top end; it bears three articular facets, with one for the preaxial accessory element (the smallest of the three), one for the radius (the tallest of the three), and one for the ulna (which forms an angle of 120° with the radial facet). Sveltonectes,[13] Nannopterygius, Platypterygius hauthali,[18] and Platypterygius platydactylus all only have two; Maiaspondylus,[19] Aegirosaurus,[4] Brachypterygius, and Platypterygius americanus[7] also have three, but the second facet articulates with a different bone; Cryopterygius has two on the left humerus and three on the right;[2] and Platypterygius australis[8] and Platypterygius hercynicus[17] have up to four facets.[1]

Hindlimb and pelvic girdle

The ilium of Keilhauia is rather short compared to that of other ophthalmosaurids; Aegirosaurus is the only other ophthalmosaurid that possibly approaches Keilhauia in this respect.[4] The side of the ilium directed towards the back of the body is concave, like Ophthalmosaurus, Athabascasaurus,[6] and Janusaurus,[15] with the curve being more pronounced in the latter two. The acetabulum, on the lower end of the ilium, is thickened relative to the rest of the bone, and does not bear any distinct articular facets. Autapomorphically, the top end of the ilium is 1.5 times the width of the acetabular end.[1]

The ischium and the pubis are fused together into a single, continuous, solid trapezoid-shaped element known as the ischiopubis, with the wider edge (1.4 times the width of the other end, which is shorter proportionally than that of Aegirosaurus,[4] Janusaurus,[15] Ophthalmosaurus, and Athabascasaurus[6]) being at the midline of the body.This complete fusion is also seen in Janusaurus,[15] Sveltonectes,[13] Athabascasaurus,[6] Aegirosaurus,[4] Caypullisaurus,[5] and possibly Platypterygius australis;[8] meanwhile, Ophthalmosaurus, Cryopterygius,[2] Undorosaurus, and Paraophthalmosaurus retain a small hole in the ischiopubis. The probable portion of the ischiopubis that represents the pubis is thicker than the rest of the bone. Also uniquely among ophthalmosaurids, this fused element is shorter than the femur.[1]

Both ends of the femur of Keilhauia are approximately the same width, with the middle of the femoral shaft being slightly narrower. The top end was slightly thicker than the rest of the bone along its front rim. Like Arthropterygius[16] but unlike Ophthalmosaurus, the femoral dorsal and ventral processes were rather reduced. At the bottom end, there are two facets, one for the tibia and one for the fibula; this is typical of ophthalmosaurids, but Platypterygius hercynicus,[17] Platypterygius americanus,[7] Platypterygius australis,[8] and Paraophthalmosaurus all have three. Both facets in Keilhauia were roughly the same length, and the fibular facet was directed slightly to the back, forming an angle of 120° with the tibial facet.[1]

Discovery and naming

Excavations led by the Spitsbergen Mesozoic Research Group from 2004 to 2012 recovered 29 ichthyosaur specimens from outcrops of the Slottsmøya Member lagerstätte, which belongs to the greater Agardhfjellet Formation, on the island of Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway. These outcrops likely date to the Tithonian-Berriasian based on ammonite biostratigraphy. From these, the new genera and species Cryopterygius kristiansenae, Palvennia hoybergeti,[2] and Janusaurus lundi[15] have previously been described.[1]

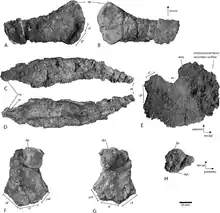

Four ichthyosaur specimens were prepared at the University of Oslo and subsequently described in 2016; they include PMO 222.655, the holotype of Keilhauia, discovered from the Berriasian portions of the Slottsmøya Member in 2010. This articulated partial skeleton, which was preserved lying on its left side, consists of part of the snout, the dorsal and anterior caudal vertebrae, the right forelimb and pectoral girdle, the majority of the pubic girdle, and both of the femora. Since all of the cervical vertebrae and parts of the dorsal vertebrae are missing, it is difficult to assign precise numberings to the existing dorsal vertebrae. The other three described specimens were PMO 222.670 and PMO 227.932, both discovered in 2011; and PMO 222.662, discovered in 2007.[1]

The genus name Keilhauia honours the Norwegian geologist Baltazar Mathias Keilhau, who conducted an expedition to Spitsbergen in 1827. Meanwhile, the species name nui is derived from the acronym of the environmental organization Natur og Ungdom, the fiftieth anniversary of which occurred in 2017.[1]

Classification

In 2017, Keilhauia was referred to the clade Ophthalmosauridae. This was on account of it bearing an articular facet on the humerus for the attachment of an anterior accessory element (a specialized limb bone that ichthyosaurs gained), as well as its forelimb elements lacking notches on their front edges.[11] A phylogenetic analysis likewise recovered Keilhauia as an ophthalmosaurid. Its specific relationships within the ophthalmosaurids, however, were difficult to elucidate due to the lack of cranial material. Thus, the authors considered the basal placement of Keilhauia in the below phylogenetic tree somewhat suspect (a similar problem occurs for Undorosaurus, which was also placed basally despite having a forelimb similar to Cryopterygius).[1]

| Ophthalmosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Keilhauia can be distinguished from its contemporaries by various characters. Unlike Cryopterygius, the ulnar facet of the humerus is angled backwards, and there is no opening in the fused ischiopubis.[2] Janusaurus has comparatively more robust humeri and more strongly-developed dorsal and ventral processes on the femur.[15] Additionally, the autapomorphies, or traits unique to this genus, provide further evidence for its distinctness.[1]

Paleobiology

A statistical analysis of ichthyosaurian proportions conducted in the description of Keilhauia showed that, throughout their evolutionary history, ichthyosaurs did not significantly reduce the relative size of their ilium, but their femora did become proportionally longer relative to their humeri. Keilhauia has a small pelvic girdle as well as a small humerus and femur, but it falls within the normal range of variation between parvipelvian ichthyosaurs.[1]

Paleoecology

The Slottsmøya Member of the Agardhfjellet Formation, from which Keilhauia is known, consists of a mix of shales and siltstones. It was deposited in a shallow marine environment, near a patch of deeper marine sediment.[20] The seafloor, which was located about 150 metres (490 ft) below the surface, seems to have been relatively dysoxic, or oxygen-poor, although it was periodically oxygenated by clastic sediments.[21] Despite this, near the top of the member, various diverse assemblages of invertebrates associated with cold seeps have been discovered; these include ammonites, lingulate brachiopods, bivalves, rhynchonellate brachiopods, tubeworms, belemnoids, tusk shells, sponges, crinoids, sea urchins, brittle stars, starfish, crustaceans, and gastropods, numbering 54 taxa in total.[22] Outside of the cold seeps, many of these invertebrates were also present in abundance.[21]

Besides Keilhauia, 16 other ichthyosaur specimens are also known from the Slottsmøya Member. These include the three that were described alongside it, as well as the type and only specimens of Cryopterygius kristiansenae, Palvennia hoybergeti,[2] and Janusaurus lundi.[15] Additionally, 21 plesiosaurian specimens are also known from the site, including two belonging to the large Pliosaurus funkei, three to Colymbosaurus svalbardensis, and one each to Spitrasaurus wensaasi and S. larseni. Many of these specimens are preserved in three dimensions and partially in articulation; this is correlated with high abundance of organic elements in the sediments they were buried in, as well as a lack of invertebrates locally.[21]

References

- Delsett, L.L.; Roberts, A.J.; Druckenmiller, P.S.; Hurum, J.H. (2017). "A New Ophthalmosaurid (Ichthyosauria) from Svalbard, Norway, and Evolution of the Ichthyopterygian Pelvic Girdle". PLOS ONE. 12 (1): e0169971. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169971. PMC 5266267. PMID 28121995.

- Druckenmiller, P.S.; Hurum, J.H.; Knutsen, E.M.; Nakrem, H.A. (2012). "Two new ophthalmosaurids (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Agardhfjellet Formation (Upper Jurassic: Volgian/Tithonian), Svalbard, Norway". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 311–339. ISSN 0029-196X.

- Johnson, R. (1977). "Size independent criteria for estimating relative age and the relationships among growth parameters in a group of fossil reptiles (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria)". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 14 (8): 1916–1924. doi:10.1139/e77-162.

- Bardet, N.; Fernandez, M. (2000). "A new ichthyosaur from the Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones of Bavaria". Journal of Paleontology. 74 (3): 503–511. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<0503:ANIFTU>2.0.CO;2.

- Fernandez, M. (2007). "Redescription and phylogenetic position of Caypullisaurus (Ichthyosauria: Ophthalmosauridae)". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (2): 368–375. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2007)81[368:RAPPOC]2.0.CO;2.

- Druckenmiller, P.S.; Maxwell, E.E. (2010). "A new Lower Cretaceous (lower Albian) ichthyosaur genus from the Clearwater Formation, Alberta, Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 47 (8): 1037–1053. doi:10.1139/E10-028.

- Maxwell, E.E.; Kear, B.P. (2010). "Postcranial anatomy of Platypterygius americanus (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria) from the Cretaceous of Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (4): 1059–1068. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.483546.

- Zammit, M.; Norris, R.M.; Kear, B.P. (2010). "The Australian Cretaceous ichthyosaur Platypterygius australis: a description and review of postcranial remains". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (6): 1726–1735. doi:10.1080/02724634.2010.521930.

- Buchholtz, E.A. (2001). "Swimming styles in Jurassic ichthyosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 61–73. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0061:SSIJI]2.0.CO;2.

- Paparella, I.; Maxwell, E.E.; Cipriani, A.; Roncace, S.; Caldwell, M.W. (2016). "The first ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaur from the Upper Jurassic of the Umbrian–Marchean Apennines (Marche, Central Italy)". Geological Magazine. 154 (4): 837–858. doi:10.1017/S0016756816000455.

- Fischer, V.; Maisch, M.W.; Naish, D.; Kosma, R.; Liston, J.; Joger, U.; Kruger, F.J.; Pardo-Perez, J.; Tainsh, J.; Appleby, R.M. (2012). "New Ophthalmosaurid Ichthyosaurs from the European Lower Cretaceous Demonstrate Extensive Ichthyosaur Survival across the Jurassic–Cretaceous Boundary". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29234. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029234. PMC 3250416. PMID 22235274.

- Fernandez, M.S; Talevi, M. (2014). "Ophthalmosaurian (Ichthyosauria) records from the Aalenian–Bajocian of Patagonia (Argentina): an overview". Geological Magazine. 151 (1): 49–59. doi:10.1017/S0016756813000058.

- Fischer, V.; Masure, E.; Arkhangelsky, M.S.; Godefroit, P. (2011). "A new Barremian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur from western Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 1010–1025. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.595464.

- Fischer, V.; Bardet, N.; Guiomar, M.; Godefroit, P. (2014). "High Diversity in Cretaceous Ichthyosaurs from Europe Prior to Their Extinction". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e84709. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084709. PMC 3897400. PMID 24465427.

- Roberts, A.J.; Druckenmiller, P.S.; Saetre, G.-P.; Hurum, J.H. (2014). "A New Upper Jurassic Ophthalmosaurid Ichthyosaur from the Slottsmøya Member, Agardhfjellet Formation of Central Spitsbergen" (PDF). PLOS ONE. 9 (8): e103152. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103152. PMC 4118863. PMID 25084533.

- Maxwell, E.E. (2010). "Generic reassignment of an ichthyosaur from the Queen Elizabeth Islands, Northwest Territories, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 403–415. doi:10.1080/02724631003617944.

- Kolb, C.; Sander, P.M. (2009). "Redescription of the ichthyosaur Platypterygius hercynicus (Kuhn 1946) from the Lower Cretaceous of Salzgitter (Lower Saxony, Germany)". Palaeontographica Abteilung A. 288 (4): 151–192. doi:10.1127/pala/288/2009/151.

- Fernandez, M.; Aguierre-Urreta, M.B. (2005). "Revision of Platypterygius hauthali von Huene, 1927 (Ichthyosauria, Ophthalmosauridae) from the Early Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 25 (3): 583–587. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0583:ROPHVH]2.0.CO;2.

- Maxwell, E.E.; Caldwell, M.W. (2006). "A new genus of ichthyosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Canada". Palaeontology. 49 (5): 1043–1052. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2006.00589.x.

- Hurum, J.H.; Nakrem, H.A.; Hammer, O.; Knutsen, E.M.; Druckenmiller, P.S.; Hryniewicz, K.; Novis, L.K. (2012). "An Arctic Lagerstätte – the Slottsmøya Member of the Agardhfjellet Formation (Upper Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous) of Spitsbergen" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 55–64. ISSN 0029-196X.

- Delsett, L.L.; Novis, L.K.; Roberts, A.J.; Koevoets, M.J.; Hammer, O.; Druckenmiller, P.S.; Hurum, J.H. (2015). "The Slottsmøya marine reptile Lagerstätte: depositional environments, taphonomy and diagenesis" (PDF). In Kear, B.P.; Lindgren, J.; Hurum, J.H.; Milan, J.; Vajda, V. (eds.). Mesozoic Biotas of Scandinavia and its Arctic Territories. Geological Society, London, Special Publications. Geological Society of London, Special Publications. 434. pp. 165–188. doi:10.1144/SP434.2.

- Hryniewicz, K.; Nakrem, H.A.; Hammer, O.; Little, C.T.S.; Kaim, A.; S., M.R.; Hurum, J.H. (2015). "The palaeoecology of the latest Jurassic–earliest Cretaceous hydrocarbon seep carbonates from Spitsbergen, Svalbard". Lethaia. 48 (3): 353–374. doi:10.1111/let.12112.