Ludwig's angina

Ludwig's angina (lat.: Angina ludovici) is a type of severe cellulitis involving the floor of the mouth.[2] Early on the floor of the mouth is raised and there is difficulty swallowing saliva, which may run from the person's mouth.[3] As the condition worsens, the airway may be compromised with hardening of the spaces on both sides of the tongue.[4] This condition has a rapid onset over hours.

| Ludwig's angina | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Angina Ludovici |

| |

| Swelling in the submandibular area in a person with Ludwig's angina. | |

| Specialty | Otorhinolaryngology, oral and maxillofacial surgery |

| Symptoms | Fever, pain, a raised tongue, trouble swallowing, neck swelling[1] |

| Complications | Airway compromise[1] |

| Usual onset | Rapid[1] |

| Risk factors | Dental infection[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and examination, CT scan[1] |

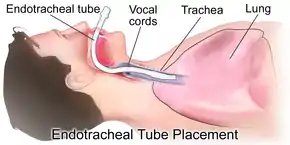

| Treatment | Antibiotics, corticosteroids, endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy[1] |

The majority of cases follow a dental infection.[3] Other causes include a parapharyngeal abscess, mandibular fracture, cut or piercing inside the mouth, or submandibular salivary stones.[5] It is a spreading infection of connective tissue through tissue spaces, normally with virulent and invasive organisms. It specifically involves the submandibular, submental, and sublingual spaces.[1]

Prevention is by appropriate dental care including management of dental infections. Initial treatment is generally with broad-spectrum antibiotics and corticosteroids.[1] In more advanced cases endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy may be required.[1]

With the advent of antibiotics in 1940s, improved oral and dental hygiene, and more aggressive surgical approach, the rates and risk of death among those infected has significantly reduced. It is named after a German physician, Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig, who first described this condition in 1836.[6]

Signs and symptoms

Ludwig's angina is a form of severe diffuse cellulitis with bilateral involvement, primarily of the submandibular space with the sublingual and submental spaces also being involved. It presents with an acute onset and spreads very rapidly meaning early diagnosis and immediate treatment planning is key to saving lives.[7] The external signs may include bilateral lower facial swelling around the mandible and upper neck. Signs inside the mouth may include elevation of the floor of mouth due to sublingual space involvement and posterior displacement of the tongue, creating the potential for a compromised airway.[7] Additional symptoms may include painful neck swelling, tooth pain, dysphagia, shortness of breath, fever, and general malaise.[8] Stridor, trismus, and cyanosis may also be seen when an impending airway crisis is nearing.[8]

Cause

The most prevalent cause of Ludwig's angina is odontogenic,[9] accounting for approximately 75% to 90% of cases.[9][10][11][12] Infections of the lower second and third molars are usually implicated due to their roots extending inferiorly below the mylohyoid muscle.[9][13] Periapical abscesses of these teeth also result in lingual cortical penetration, leading to submandibular infection.[9]

However, oral ulcerations, infections of oral malignancy, mandible fracture, bilateral sialolithiasis-related submandibular gland infection,[9] and penetrating injuries of the mouth floor[14] have also been reported as potential causes of Ludwig's angina. In fact, the same microorganisms responsible for less morbid head and neck infections are found in causing extensive infection throughout the floor of mouth and neck[14] when Ludwig's angina is critically reviewed.[9] Patients with systemic illness, such as diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, compromised immune system, and organ transplantation are also commonly predisposed to Ludwig's angina.[12]

It is found that one third of the cases of Ludwig's angina are associated with systemic illness.[12] A review reporting the incidence of illnesses associated with Ludwig angina found that 18% of cases involved diabetes mellitus, 9% involved acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and another 5% were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive.[15]

Diagnosis

Infections originating in the roots of teeth can be identified with a dental X-ray.[16][17] A CT scan of the neck with contrast material is used to identify deep neck space infections.[18] If there is suspicion of the infection of the chest cavity, a chest scan is sometimes done.[17]

Angioneurotic oedema, lingual carcinoma and sublingual haematoma formation following anticoagulation should be ruled out as possible diagnoses.[18]

Microbiology

There are a few methods that can be used for determining the microbiology of Ludwig's angina. One of the traditionally used methods is taking culture samples although it has some limitations.[19][20] By taking pus samples from a patient with Ludwig's angina, the microbiology were found to be commonly polymicrobial and anaerobic.[21][22] Some of the commonly found microbes are Viridans Streptococci, Staphylococci, Peptostreptococci, Prevotella, Porphyromonas and Fusobacterium.[21][22]

Treatment

For each patient, the treatment plan should be done with consideration of each of the individual patient's differing factors. They are namely the stage of the disease and co-morbid conditions at the time of presentation, physician experience, available resources, and personnel are critical factors in formulation of a treatment plan.[23] There are four principles that guide the treatment of Ludwig's Angina:[24] Sufficient airway management, early and aggressive antibiotic therapy, incision and drainage for any who fail medical management or form localized abscesses, and adequate nutrition and hydration support. Each will be explained in detail below.

Airway management

Airway management has been found to be the most important factor in treating patients with Ludwig's Angina,[19] i.e. it is the “primary therapeutic concern”.[25] Airway compromise is known to be the leading cause of death from Ludwig's Angina.[5]

- The basic method to achieve this is to allow the patient to sit in an upright position, with supplemental oxygen provided by masks or nasal prongs.[19] Patients should never be left unattended, particularly if there is an absence of intubation or a surgical airway in place.[19]

- Methods of airway management range from conservative airway management – consisting of close observation and intravenous antibiotics, to airway intervention with endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy.[19]

- If the oxygen saturation levels are adequate and antimicrobials have been given, simple airway observation can be done.[19] This is a suitable method to adopt in the management of children, as a retrospective study described that only 10% of children required airway control. However, a tracheostomy was performed on 52% of those affected with Ludwig's Angina over 15 years old.[26]

- Airway control is compulsory if a surgical procedure is required.[5]

- Flexible nasotracheal intubation require skills and experience.[5]

- If nasotracheal intubation is not possible, cricothyrotomy and tracheostomy under local anaesthetic can be done. This procedure is carried out on patients with advanced stage of Ludwig's Angina.[5]

- Endotracheal intubation has been found to be in association with high failure rate with acute deterioration in respiratory status.[5]

- Elective tracheostomy is described as a safer and more logical method of airway management in patients with fully developed Ludwig's Angina.[27]

- Fibre-optic nasoendoscopy can also be used, especially for patients with floor of mouth swellings.[19]

- It is important that incision and drainage are preceded by consulting the anaesthesiologist about possible airway problems at intubation.[19] A tracheostomy set should always be present in the operating room in case there is requirement for local tracheostomy or an emergency cricothyrotomy.[19]

Antibiotics

- Antibiotic therapy is empirical, it is given until culture and sensitivity results are obtained.[19] The empirical therapy should be effective against both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria species commonly involved in Ludwig's Angina.[19] Only when culture and sensitivity results return should therapy be tailored to the specific requirements of the patient.[19]

- Empirical coverage should consist of either a penicillin with a B-lactamase inhibitor such as amoxicillin/ticarcillin with clavulanic acid or a Beta-lactamase resistant antibiotic such as cefoxitin, cefuroxime, imipenem or meropenem.[19] This should be given in combination with a drug effective against anaerobes such as clindamycin or metronidazole.[19]

- Parenteral antibiotics are suggested until the patient is no longer febrile for at least 48 hours.[19] Oral therapy can then commence to last for 2 weeks, with amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, clindamycin, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or metronidazole.[19]

Incision and drainage

- Surgical incision and drainage are the main methods in managing severe and complicated deep neck infections that fail to respond to medical management within 48 hours.[19]

- It is indicated in cases of:[19]

- Airway compromise

- Septicaemia

- Deteriorating condition

- Descending infection

- Diabetes mellitus

- Palpable or radiographic evidence of abscess formation

- Bilateral submandibular incisions should be carried out in addition to a midline submental incision. Access to the supramylohyoid spaces can be gained by blunt dissection through the mylohyoid muscle from below.[19]

- Penrose drains are recommended in both supramylohyoid and inframylohyoid spaces bilaterally. In addition, through and through drains from the submandibular space to the submental space on both sides should be placed as well.[19]

- The incision and drainage process is completed with the debridement of necrotic tissue and thorough irrigation.[19]

- It is necessary to mark drains in order to identify their location. They should be sutured with loops as well so it will be possible to advance them without re-anaesthetizing the patient while drains are re-sutured to the skin.[19]

- An absorbent dressing is then applied. A bandnet dressing retainer can be constructed so as to prevent the use of tape.[19]

Nutritional support

Adequate nutrition and hydration support is essential in deciding the outcomes in any patient following surgery, particularly young children.[24] In this case, pain and swelling in the neck region would usually cause difficulties in eating or swallowing, hence reducing patient's food and fluid intake. As a result, patients suffer from weight loss due to loss of fat, muscle and skin initially, followed by bone and internal organs in the late phase. Meanwhile, at the cellular level, the cells would be less able to maintain homeostasis in the presence of stressors such as infection and surgery. Patients must therefore be well-nourished and hydrated to promote wound healing and to fight off infection.[28]

Post-operative care

Extubation, which is the removal of endotracheal tube to liberate the patient from mechanical ventilation, should only be done when the patient's airway is proved to be patent, allowing adequate breathing. This is indicated by a decrease in swelling and patient's capability of breathing adequately around an uncuffed endotracheal tube with the lumen blocked.[28]

During the hospital stay, patient's condition will be closely monitored by:

- carrying out cultures and sensitivity tests to decide if any changes need to be made to patient's antibiotic course

- observing patient's body temperature - a rise implies further infection

- monitoring patient's white blood cell count - a decrease implies effective and sufficient drainage

- repeating CT scans to prove patient's restored health status or if infection extends, the anatomical areas that are affected.[28]

Moreover, it is advised to never leave young children with significant neck swelling unattended and they should always be seated to prevent suffocation.[24]

Etymology

The term “angina”, is derived from the Latin word “angere”, which means “choke”; and the Greek word “ankhone”, which means “strangle”. Placing it into context, Ludwig's angina refers to the feeling of strangling and choking, secondary to obstruction of the airway, which is the most serious potential complication of this condition.[22]

See also

References

- Gottlieb, M; Long, B; Koyfman, A (May 2018). "Clinical Mimics: An Emergency Medicine-Focused Review of Streptococcal Pharyngitis Mimics". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 54 (5): 619–629. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.031. PMID 29523424.

- Candamourty R, Venkatachalam S, Babu MR, Kumar GS (July 2012). "Ludwig's Angina - An emergency: A case report with literature review". Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine. 3 (2): 206–8. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.101932. PMC 3510922. PMID 23225990.

- Coulthard P, Horner K, Sloan P, Theaker ED (2013-05-17). Master dentistry (3rd ed.). Edinburgh: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7020-4600-1. OCLC 786161764.

- Kremer MJ, Blair T (December 2006). "Ludwig angina: forewarned is forearmed". AANA Journal. 74 (6): 445–51. PMID 17236391.

- Saifeldeen K, Evans R (March 2004). "Ludwig's angina". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (2): 242–3. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.012336. PMC 1726306. PMID 14988363.

- Murphy SC (October 1996). "The person behind the eponym: Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig (1790-1865)". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine. 25 (9): 513–5. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0714.1996.tb00307.x. PMID 8959561.

- Candamourty, Ramesh; Venkatachalam, Suresh; Babu, M. R. Ramesh; Kumar, G. Suresh (2012). "Ludwig's Angina – An emergency: A case report with literature review". Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine. 3 (2): 206–208. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.101932. ISSN 0976-9668. PMC 3510922. PMID 23225990.

- Saifeldeen, K.; Evans, R. (2004-03-01). "Ludwig's angina". Emergency Medicine Journal. 21 (2): 242–243. doi:10.1136/emj.2003.012336. ISSN 1472-0205. PMC 1726306. PMID 14988363.

- Current therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Bagheri, Shahrokh C., Bell, R. Bryan., Khan, Husain Ali. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. 2012. ISBN 9781416025276. OCLC 757994410.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Moreland, L. W.; Corey, J.; McKenzie, R. (February 1988). "Ludwig's angina. Report of a case and review of the literature". Archives of Internal Medicine. 148 (2): 461–466. doi:10.1001/archinte.1988.00380020205027. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 3277567.

- Sethi, D. S.; Stanley, R. E. (February 1994). "Deep neck abscesses--changing trends". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 108 (2): 138–143. doi:10.1017/S0022215100126106. ISSN 0022-2151. PMID 8163915.

- Chou, Yu-Kung; Lee, Chao-Yi; Chao, Hai-Hsuan (December 2007). "An upper airway obstruction emergency: Ludwig angina". Pediatric Emergency Care. 23 (12): 892–896. doi:10.1097/pec.0b013e31815c9d4a. ISSN 1535-1815. PMID 18091599. S2CID 2891390.

- Prince, Jim McMorran, Damian Crowther, Stew McMorran, Steve Youngmin, Ian Wacogne, Jon Pleat, Clive. "Ludwig's angina - General Practice Notebook". gpnotebook.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- "Peterson's Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 2nd Ed 2004". Scribd. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

- Moreland, Larry W. (1988-02-01). "Ludwig's Angina". Archives of Internal Medicine. 148 (2): 461–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.1988.00380020205027. ISSN 0003-9926. PMID 3277567.

- Spitalnic SJ, Sucov A (July 1995). "Ludwig's angina: case report and review". The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 13 (4): 499–503. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(95)80007-7. PMID 7594369.

- Bagheri SC (2014). Clinical Review of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: A Case-Based Approach (Second ed.). St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier. pp. 95–118. ISBN 978-0-323-17127-4.

- Crespo AN, Chone CT, Fonseca AS, Montenegro MC, Pereira R, Milani JA (November 2004). "Clinical versus computed tomography evaluation in the diagnosis and management of deep neck infection". Sao Paulo Medical Journal. 122 (6): 259–63. doi:10.1590/S1516-31802004000600006. PMID 15692720.

- Bagheri SC, Bell RB, Khan HA (2011). Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 1092–1098. ISBN 978-1-4160-2527-6.

- Siqueira JF, Rôças IN (April 2013). "Microbiology and treatment of acute apical abscesses". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (2): 255–73. doi:10.1128/CMR.00082-12. PMC 3623375. PMID 23554416.

- Candamourty R, Venkatachalam S, Babu MR, Kumar GS (July 2012). "Ludwig's Angina - An emergency: A case report with literature review". Journal of Natural Science, Biology, and Medicine. 3 (2): 206–8. doi:10.4103/0976-9668.101932. PMC 3510922. PMID 23225990.

- Costain N, Marrie TJ (February 2011). "Ludwig's Angina". The American Journal of Medicine. 124 (2): 115–7. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.08.004. PMID 20961522.

- Shockley WW (May 1999). "Ludwig angina: a review of current airway management". Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 125 (5): 600. doi:10.1001/archotol.125.5.600. PMID 10326825.

- Chou YK, Lee CY, Chao HH (December 2007). "An upper airway obstruction emergency: Ludwig angina". Pediatric Emergency Care. 23 (12): 892–6. doi:10.1097/pec.0b013e31815c9d4a. PMID 18091599. S2CID 2891390.

- Moreland LW, Corey J, McKenzie R (February 1988). "Ludwig's angina. Report of a case and review of the literature". Archives of Internal Medicine. 148 (2): 461–6. doi:10.1001/archinte.1988.00380020205027. PMID 3277567.

- Kurien M, Mathew J, Job A, Zachariah N (June 1997). "Ludwig's angina". Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 22 (3): 263–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00014.x. PMID 9222634.

- Parhiscar A, Har-El G (November 2001). "Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 110 (11): 1051–4. doi:10.1177/000348940111001111. PMID 11713917. S2CID 40027551.

- Bagheri SC, Bell RB, Khan HA (2012). Current Therapy in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4160-2527-6. OCLC 757994410.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |