Lycorine

Lycorine is a toxic crystalline alkaloid found in various Amaryllidaceae species, such as the cultivated bush lily (Clivia miniata), surprise lilies (Lycoris), and daffodils (Narcissus). It may be highly poisonous, or even lethal, when ingested in certain quantities.[1] Regardless, it is sometimes used medicinally, a reason why some groups may harvest the very popular Clivia miniata.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1,2,4,5,12b,12c-Hexahydro-7H-[1,3]dioxolo[4,5-j]pyrrolo[3,2,1-de]phenanthridine-1,2-diol | |

| Other names

Galanthidine, Amarylline, Narcissine, Licorine, Belamarine | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.822 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C16H17NO4 | |

| Molar mass | 287.315 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Source

Lycorine is found in different species of Amaryllidaceae which include flowers and bulbs of daffodil, snowdrop (Galanthus) or spider lily (Lycoris). Lycorine is the most frequent alkaloid of Amaryllidaceae.[2]

The earliest diversification of Amaryllidaceae was most likely in North Africa and the Iberian peninsula and that lycorine is one of the oldest in the Amaryllidaceae alkaloid biosynthetic pathway.[3]

Mechanism of action

There is currently very little known about the mechanism of lycorine. There are tentative ideas about how lycorine metabolizes due to a study done on beagle dogs.[4]

Lycorine inhibits protein synthesis,[5] and may inhibit ascorbic acid biosynthesis, although studies on the latter are controversial and inconclusive. Presently, it serves some interest in the study of certain yeasts, the principal organism on which lycorine is tested.[6]

It is known that lycorine weakly inhibits acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and ascorbic acid biosynthesis.[7] The IC50 of lycorine was found to vary between the different species it can be found in, but a common deduction from the experiments on lycorine was that it had some effect on inhibiting AChE.[8]

Lycorine exhibits cytostatic effects by targeting the actin cytoskeleton rather than by inducing apoptosis in cancer cells, though lycorine was found to apoptosis at different stages in a cells cycle.[9]

Biosynthesis

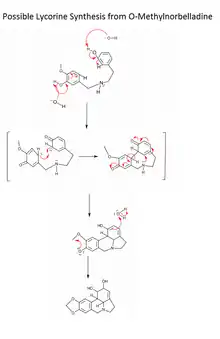

One possible synthesis of lycorine could come from O-Methylnorbelladine, which can be seen in the image to the right.

Toxicity

The poisoning of lycorine typically occurs with the ingestion of daffodil bulbs. Daffodil bulbs are sometimes confused with onions, leading to accidental poisoning.[10]

In a study of dosage used on beagle dogs, the first sign of nausea was observed at as little of a dose of 0.5 mg/kg and occurred within a 2.5 hour span. The effective dose to induce emesis in the dogs was seen to be 2.0 mg/kg and lasted no longer than 2.5 hours after administration.[11]

Current research

Lycorine has been seen to have promising biological and pharmacological activities such as antibacterial, antiviral, or anti-inflammatory effects and may have anticancer properties.[14] It has displayed various inhibitory properties towards multiple cancer cell lines that include, lymphoma, carcinoma, multiple myeloma, melanoma, leukemia, human A549 non-small-cell lung cancer, human OE21 esophageal cancer and more.[15]

Lycorine has many derivatives used for anti-cancer research such as lycorine hydrochloride (LH) which is a novel anti-ovarian cancer agent, and data has shown that LH effectively inhibited mitotic proliferation of Hey1B cells with very low toxicity. This drug could be used for effective anti-ovarian cancer therapy in the future.[16]

References

- "T3DB: Lycorine". www.t3db.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-12.

- Jahn, Sandra; Seiwert, Bettina; Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Regenthal, Ralf; Karst, Uwe (2012). "Metabolic studies of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloids galantamine and lycorine based on electrochemical simulation in addition to in vivo and in vitro models". Analytica Chimica Acta. 756 (756): 60–72. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.042. PMID 23176740. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Berkov, Strahil; Martinez-Frances, Vanessa; Bastida, Jaume; Codina, Carles; Rios, Sequndo (2014). "Evolution of alkaloid biosynthesis in the genus Narcissus". Phytochemistry. 99 (99): 95–106. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.11.002. PMID 24461780.

- Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Seiwert, Bettina; Ungemach, Fritz Rupert; Krugel, Ute; Regenthal, Ralf (2011). "Dose-dependent emetic effects of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloid lycorine in beagle dogs". Toxicon. 57 (57): 117–124. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.10.012. PMID 21055413. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Vrijsen R, Vanden Berghe DA, Vlietinck AJ, Boeyé A (1986). "Lycorine: a eukaryotic termination inhibitor?". J. Biol. Chem. 261 (2): 505–7. PMID 3001065.

- Garuccio I, Arrigoni O (1989). "[Various sensitivities of yeasts to lycorine]". Boll. Soc. Ital. Biol. Sper. (in Italian). 65 (6): 501–8. PMID 2611011.

- Jahn, Sandra; Seiwert, Bettina; Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Regenthal, Ralf; Karst, Uwe (2012). "Metabolic studies of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloids galantamine and lycorine based on electrochemical simulation in addition to in vivo and in vitro models". Analytica Chimica Acta. 756 (756): 60–72. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.042. PMID 23176740. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Elisha, I.L.; Elgorashi, E.E.; Hussein, A.A.; Duncan, G.; Eloff, J.N. (2013). "Acetlycholinesterase inhibitory effects of the bulb of Ammocharis coranica (Amaryllidaceae) and its active constituent lycorine". South African Journal of Botany (85): 44–47. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Wang, Peng; Yuan, Hui-Hui; Zhang, Xue; Li, Yun-Ping; Shang, Lu-Qing; Yin, Zheng (21 February 2014). "Novel Lycorine Derivatives as Anticancer Agents: Synthesis and In Vitro Biological Evaluation". Molecules. 19 (2): 2469–2480. doi:10.3390/molecules19022469. PMC 6271160. PMID 24566315. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Pupils ill after bulb put in soup, BBC News, 3 May 2009

- Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Seiwert, Bettina; Ungemach, Fritz Rupert; Krugel, Ute; Regenthal, Ralf (2011). "Dose-dependent emetic effects of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloid lycorine in beagle dogs". Toxicon. 57 (57): 117–124. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.10.012. PMID 21055413. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Seiwert, Bettina; Ungemach, Fritz Rupert; Krugel, Ute; Regenthal, Ralf (2011). "Dose-dependent emetic effects of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloid lycorine in beagle dogs". Toxicon. 57 (57): 117–124. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.10.012. PMID 21055413. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Lycorine, definition at mercksource.com

- Jahn, Sandra; Seiwert, Bettina; Kretzing, Sascha; Abraham, Getu; Regenthal, Ralf; Karst, Uwe (2012). "Metabolic studies of the Amaryllidaceous alkaloids galantamine and lycorine based on electrochemical simulation in addition to in vivo and in vitro models". Analytica Chimica Acta. 756 (756): 60–72. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2012.10.042. PMID 23176740. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Wang, Peng; Yuan, Hui-Hui; Zhang, Xue; Li, Yun-Ping; Shang, Lu-Qing; Yin, Zheng (21 February 2014). "Novel Lycorine Derivatives as Anticancer Agents: Synthesis and In Vitro Biological Evaluation". Molecules. 19 (2): 2469–2480. doi:10.3390/molecules19022469. PMC 6271160. PMID 24566315. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Cao, Zhifei; Yu, Di; Fu, Shilong; Zhang, Gaochuan; Pan, Yanyan; Bao, Meimei; Tu, Jian; Shang, Bingxue; Guo, Pengda; Yang, Ping; Zhou, Quansheng (2013). "Lycorine hydrochloride selectively inhibits human ovarian cancer cell proliferation and tumor neovascularization with very low toxicity". Toxicology Letters. 218 (2): 174–185. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.01.018. PMID 23376478. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

External links

- Hill, R. K.; Joule, J. A.; Loeffler, L. J. (1962). "Stereoselective Syntheses of d,l-α- and β-Lycoranes". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 84 (24): 4951–4956. doi:10.1021/ja00883a064.

- Wolfgang Oppolzer; Alan C. Spivey & Christian G. Bochet (1994). "Suprafaciality of Thermal N-4-Alkenylhydroxylamine Cyclizations: Syntheses of (±)-α-Lycorane and (+)-Tianthine" (PDF). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116 (7): 3139–3140. doi:10.1021/ja00086a060. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-14. Retrieved 2009-11-04.