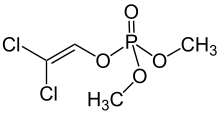

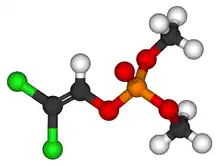

Dichlorvos

Dichlorvos (2,2-dichlorovinyl dimethyl phosphate, commonly abbreviated as an DDVP[1]) is an organophosphate widely used as an insecticide to control household pests, in public health, and protecting stored products from insects. The compound has been commercially available since 1961 and has become controversial because of its prevalence in urban waterways and the fact that its toxicity extends well beyond insects.[2] The insecticide has been banned in EU since 1998.[3]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | DDVP, Vapona etc.[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| ATCvet code | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.498 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H7Cl2O4P |

| Molar mass | 220.97 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Use

Dichlorvos is effective against mushroom flies, aphids, spider mites, caterpillars, thrips, and whiteflies in greenhouses and in outdoor crops. It is also used in the milling and grain handling industries and to treat a variety of parasitic worm infections in animals and humans. It is fed to livestock to control bot fly larvae in manure. It acts against insects as both a contact and a stomach poison. It is available as an aerosol and soluble concentrate. It is also used in pet collars and "no-pest strips" in the form of a pesticide-impregnated plastic; this material has been available to households since 1964 and has been the source of some concern, partly due to its misuse.[4]

Mechanism of action

Dichlorvos, like other organophosphate insecticides, acts on acetylcholinesterase, associated with the nervous systems of insects. Evidence for other modes of action, applicable to higher animals, have been presented.[5][6] It is claimed to damage DNA of insects.[7]

Regulation

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has reviewed the safety data of dichlorvos several times.[8] In 1995 a voluntary agreement was reached with the supplier, Amvac Chemical Corporation, which restricted the use of dichlorvos in many, but not all, domestic uses, all aerial applications, and other uses.[9] Additional voluntary cancellations were implemented in 2006, 2008 and 2010. Major concerns focus on acute and chronic toxicity and the fact that this pesticide is prevalent in urban waterways.[10] A 2010 study found that each 10-fold increase in urinary concentration of organophosphate metabolites was associated with a 55% to 72% increase in the odds of ADHD in children.[11][12][13]

Safety

People can be exposed to dichlorvos in the workplace by breathing it in, skin absorption, swallowing it, and eye contact. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for dichlorvos exposure in the workplace as 1 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has set a recommended exposure limit (REL) of 1 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday. At levels of 100 mg/m3, dichlorvos is immediately dangerous to life and health.[14]

Effects on humans

Since it is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, symptoms of dichlorvos exposure include weakness, headache, tightness in chest, blurred vision, salivation, sweating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps, eye and skin irritation, miosis (pupil constriction), eye pain, runny nose, wheezing, laryngospasm, cyanosis, anorexia, muscle fasciculation, paralysis, dizziness, ataxia, convulsions, hypotension (low blood pressure), and cardiac arrhythmias.[14]

It is also known to affect DNA growth,[15] and interfere with the human nervous system.[16]

| Dose | Organism | Time |

|---|---|---|

| 15 mg/m3 | rat | 4 h |

| 13 mg/m3 | mouse | 4 h |

| Dose | Organism | Route |

|---|---|---|

| 100 mg/kg | dog | oral |

| 61 mg/kg | mouse | oral |

| 10 mg/kg | rabbit | oral |

| 17 mg/kg | rat | oral |

Pop culture

Dichlorvos is mentioned in John Brunner's science fiction novel The Sheep Look Up. One of the book's many vignettes tells of a woman who nearly dies, having taken barbiturates and gone to sleep in a closed room where a fly-killing strip doused with the material was placed.[18]

See also

References

- "Dichlorvos". Haz-Map. U.S. National Library of Medicine. August 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-13.

- Das S (2013). "A review of Dichlorvos toxicity in fish". Current World Environment Journal. 8 (1). doi:10.12944/CWE.8.1.08.

- "Which pesticides are banned in Europe?" (PDF). pan-europe.info. 2008.

- Gillett JW, Harr JR, Lindstrom FT, Mount DA, St Clair AD, Weber LJ (1972). "Evaluation of human health hazards on use of dichlorvos (DDVP), especially in resin strips". Residue Reviews. 44: 115–59. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-8491-9_6. ISBN 978-0-387-05863-4. PMID 4576326.

- Pancetti F, Olmos C, Dagnino-Subiabre A, Rozas C, Morales B (December 2007). "Noncholinesterase effects induced by organophosphate pesticides and their relationship to cognitive processes: implication for the action of acylpeptide hydrolase". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part B. 10 (8): 623–30. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.334.9406. doi:10.1080/10937400701436445. PMID 18049927.

- Booth ED, Jones E, Elliott BM (December 2007). "Review of the in vitro and in vivo genotoxicity of dichlorvos". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 49 (3): 316–26. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2007.08.011. PMID 17936460.

- Espeland M, Irestedt M, Johanson KA, Akerlund M, Bergh JE, Källersjö M (January 2010). "Dichlorvos exposure impedes extraction and amplification of DNA from insects in museum collections". Frontiers in Zoology. 7: 2. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-7-2. PMC 2819063. PMID 20148102.

- Mennear JH (June 1998). "Dichlorvos: a regulatory conundrum". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 27 (3): 265–72. doi:10.1006/rtph.1998.1217. PMID 9693077.

- "Dichlorvos (DDVP): Deletion of Certain Uses and Directions". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Office of Pesticide Programs. April 19, 1995. pp. 19580–19581.

Docket Control Number OPP-38511.

- Wines M (11 September 2014). "Pesticide Levels in Waterways Have Dropped, Reducing the Risks to Humans". The New York Times.

- Brooks M (May 17, 2010). "Organophosphate Pesticides Linked to ADHD". Medscape.

- Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, Weisskopf MG (June 2010). "Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides" (PDF). Pediatrics. 125 (6): e1270-7. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3058. PMC 3706632. PMID 20478945.

- Raeburn P (August 14, 2006). "Slow-Acting". Scientific American. Vol. 295 no. 2. p. 26. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0806-26.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0202". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Preferential Effect of Dichlorvos(Vapona) on Bacteria deficient in DNA polymerase" (PDF). Cancer Research.

- "Big Court win for public health". www.nrdc.org.

- "Dichlorvos". Immediately Dangerous to Life and Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Brunner, John (1972). The Sheep Look Up. New York: Ballantine Books. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-06-010558-7. LCCN 72-79705.

External links

- Extension Toxicology Network fact sheet

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Australian Pesticides & Veterinary Medicines Authority Chemical Review Program - Dichlorvos

- Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for Dichlorvos

- Raeburn P (August 2006). "Slow-acting". Scientific American. 295 (2): 26. Bibcode:2006SciAm.295b..26R. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0806-26. PMID 16866280.

- BBC News: Insecticide ban amid cancer fears