Transition metal thiolate complex

Transition metal thiolate complexes are metal complexes containing thiolate ligands. Thiolates are ligands that can be classified as soft Lewis bases. Therefore, thiolate ligands coordinate most strongly to metals that behave as soft Lewis acids as opposed to those that behave as hard Lewis acids. Most complexes contain other ligands in addition to thiolate, but many homoleptic complexes are known with only thiolate ligands. The amino acid cysteine has a thiol functional group, consequently many cofactors in proteins and enzymes feature cysteinate-metal cofactors.[1]

Synthesis

Metal thiolate complexes are commonly prepared by reactions of metal complexes with thiols (RSH), thiolates (RS−), and disulfides (R2S2). The salt metathesis reaction route is common. In this method, an alkali metal thiolate is treated with a transition metal halide to produce an alkali metal halide and the metal thiolate complex:

- LiSC6H5 + CuI → Cu(SC6H5) + LiI

The thiol ligand can also effect protonolysis of anionic ligands, as illustrated by the formation of an organonickel thiolate from nickelocene and ethanethiol:

- 2 HSC2H5 + 2 Ni(C5H5)2 → [Ni(SC2H5)(C5H5)]2 + 2 C5H6

Redox routes

Many thiolate complexes are prepared by redox reactions. Organic disulfides oxidize low valence metals, as illustrated by the oxidation of titanocene dicarbonyl:

- (C5H5)2Ti(CO)2 + (C6H5S)2 → (C5H5)2Ti(SC6H5)2 + 2 CO

Some metal centers are oxidized by thiols, the coproduct being hydrogen gas:

- Fe3(CO)12 + 2 C2H5SH → Fe2(SC2H5)2(CO)6 + Fe(CO)5 + CO + H2

These reactions probably proceed via oxidative addition of the thiol.

Thiols and especially thiolate salts are reducing agents. Consequently, they induce redox reactions with certain transition metals. This phenomenon is illustrated by the synthesis of cuprous thiolates from cupric precursors:

- 4 HSC6H5 + 2 CuO → 2 Cu(SC6H5) + (C6H5S)2 + 2 H2O

Thiolate clusters of the type [Fe4S4(SR)4]2− occur in iron–sulfur proteins. Synthetic analogues can be prepared by combined redox and salt metathesis reactions:[3]

- 4 FeCl3 + 6 NaSR + 6 NaSH → Na2[Fe4S4(SR)4] + 10 NaCl + 4 HCl + H2S + R2S2

Structure and bonding

Divalent sulfur exhibits bond angles approaching 90°. Such acute angles are also seen in the M-S-C angles of metal thiolates. Having filled p-orbitals of suitable symmetry, thiolates are pi-donor ligands. This property plays a role in the stabilization of Fe(IV) states in the enzyme cytochrome P450.

Reactions

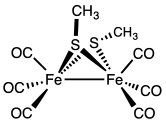

Thiolates are relatively basic ligands, being derived from conjugate acids with pKa's of 6.5 (thiophenol) to 10.5 (butanethiol). Consequently, thiolate ligand often bridge pairs of metals. One example is Fe2(SCH3)2(CO)6. Thiolate ligands, especially when nonbridging, are susceptible to attack by electrophiles including acids, alkylating agents, and oxidants.

Occurrence and applications

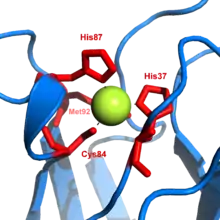

Metal thiolate functionality is pervasive in metalloenzymes. Iron-sulfur proteins, blue copper proteins, and the zinc-containing enzyme liver alcohol dehydrogenase feature thiolate ligands. Commonly thiolate is ligand is provided from the cysteine residue. All molybdoproteins feature thiolates in the form of cysteinyl and/or molybdopterin.[5]

References

- Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-19957-5

- Axel Kern, Christian Näther, Felix Studt, Felix Tuczek (2004). "Application of a Universal Force Field to Mixed Fe/Mo−S/Se Cubane and Heterocubane Clusters. 1. Substitution of Sulfur by Selenium in the Series [Fe4X4(YCH3)4]2-; X = S/Se and Y = S/Se". Inorg. Chem. 43: 5003–5010. doi:10.1021/ic030347d. PMID 15285677.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Lee, S. C.; Lo, W.; Holm, R. H. (2014). "Developments in the Biomimetic Chemistry of Cubane-Type and Higher Nuclearity Iron–Sulfur Clusters". Chemical Reviews. 114: 3579–3600. doi:10.1021/cr4004067. PMC 3982595. PMID 24410527.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Nguyen, T.; Panda, A.; Olmstead, M. M.; Richards, A. F.; Stender, M.; Brynda, M.; Power, P. P. (2005). "Synthesis and Characterization of Quasi-Two-Coordinate Transition Metal Dithiolates M(SAr)2 (M = Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn; Ar = C6H3-2,6(C6H2-2,4,6-Pri3)2)". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127: 8545–8552. doi:10.1021/ja042958q.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- S. J. Lippard, J. M. Berg “Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry” University Science Books: Mill Valley, CA; 1994. ISBN 0-935702-73-3.