Trilostane

Trilostane, sold under the brand names Modrenal and Vetoryl among others, is a medication which has been used in the treatment of Cushing's syndrome, Conn's syndrome, and postmenopausal breast cancer in humans.[2][3][4][5][1] It was withdrawn for use in humans in the United States in the 1990s[6] but was subsequently approved for use in veterinary medicine in the 2000s to treat Cushing's syndrome in dogs.[7] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Desopan, Modrastane, Modrenal, Trilox, Vetoryl, Winstan |

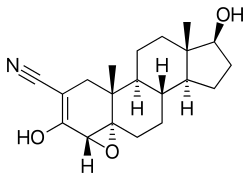

| Other names | WIN-24,540; 4α,5-Epoxy-3,17β-dihydroxy-5α-androst-2-ene-2-carbonitrile |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Metabolites | 17-Ketotrilostane[1] |

| Elimination half-life | Trilostane: 1.2 hours[1] 17-Ketotrilostane: 1.2 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.743 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C20H27NO3 |

| Molar mass | 329.440 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Medical uses

Trilostane has been used in the treatment of Cushing's syndrome (hypercortisolism), Conn's syndrome (hyperaldosteronism), and postmenopausal breast cancer in humans.[3][1] When used to treat breast cancer, trilostane is administered in combination with a corticosteroid to prevent glucocorticoid deficiency.[1]

Veterinary uses

Trilostane is used for the treatment of Cushing's syndrome in dogs. The safety and effectiveness of trilostane for this indication were shown in several studies.[8][9] Success was measured by improvements in both blood test results and physical symptoms (normalized appetite and activity level, and decreased panting, thirst, and urination).[8][9]

Contraindications

Trilostane should not be used in pregnant women.[1]

Trilostane should not be given to a dog that:

- Has kidney or liver disease[10][11]

- Takes certain medications used to treat cardiovascular disease[12]

- Is pregnant, nursing or intended for breeding[10][11]

Side effects

Side effects of trilostane in conjunction with a corticosteroid in humans include gastrointestinal side effects like gastritis, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.[1] Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may decrease the incidence of diarrhea with trilostane.[1] Serious gastrointestinal side effects of trilostane alone or in combination with an NSAID like peptic ulcer, erosive gastritis, gastric perforation, hematemesis, and melena may occur in some individuals.[1] Reversible granulocytopenia and transient oral paresthesia may occur with trilostane.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

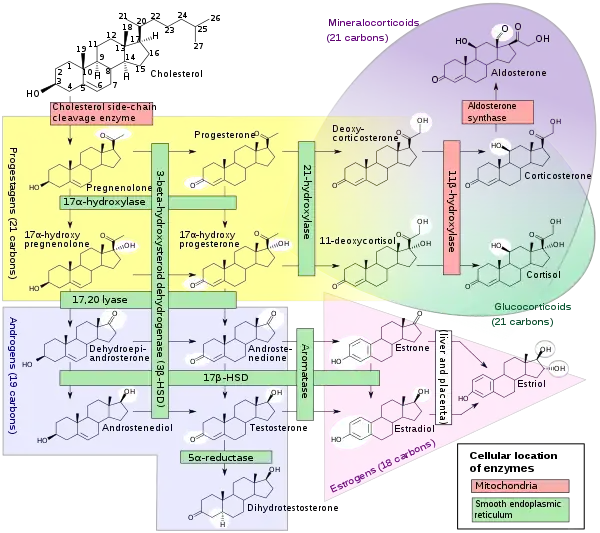

Trilostane is a steroidogenesis inhibitor.[1] It is specifically an inhibitor of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD).[1][13] As a result of this action, trilostane blocks the conversion of Δ5-3β-hydroxysteroids, including pregnenolone, 17α-hydroxypregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and androstenediol, into Δ4-3-ketosteroids, including progesterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, androstenedione, and testosterone, respectively.[1] Consequently, trilostane inhibits the production of all classes of steroid hormones, including androgens, estrogens, progestogens, glucocorticoids, and mineralocorticoids.[1]

The mechanism of action of trilostane in Cushing's syndrome and Conn's syndrome is by inhibiting the production of corticosteroids such as cortisol and aldosterone in the adrenal glands.[14][15] Trilostane has also been used as an abortifacient due to its inhibition of progesterone synthesis.[1][16]

Trilostane is not an aromatase inhibitor and hence does not inhibit the conversion of androgens like androstenedione and testosterone into estrogens like estrone and estradiol.[1] However, trilostane may nonetheless inhibit estrogen synthesis by inhibiting androgen synthesis.[1]

In addition to steroidogenesis inhibition, trilostane has been found to act as a noncompetitive antiestrogen, via direct and presumably allosteric interactions with the estrogen receptor.[1][17][18] The effectiveness of trilostane in postmenopausal breast cancer may relate this apparent antiestrogenic activity.[1][17][18] Trilostane has also been found to act as an agonist of the androgen receptor.[19] As such, its use in men with prostate cancer may warrant caution.[1]

Pharmacokinetics

Trilostane is metabolized in the liver.[1] The major metabolite of trilostane is 17-ketotrilostane.[1] The conversion of trilostane into 17-ketotrilostane is reversible, suggesting that trilostane and 17-ketotrilostane undergo interconversion in the body.[1] 17-Ketotrilostane circulates at 3-fold higher levels than trilostane and is more active than trilostane as a 3β-HSD inhibitor.[1] The elimination half-lives of trilostane and 17-ketotrilostane are both 1.2 hours, with both compounds cleared from the blood within 6 to 8 hours of a dose of trilostane.[1] 17-Ketotrilostane is excreted by the kidneys.[1]

Chemistry

Trilostane, also known as 4α,5-epoxy-3,17β-dihydroxy-5α-androst-2-ene-2-carbonitrile, is a synthetic androstane steroid and a derivative of 5α-reduced androstane derivatives like 3α-androstanediol, 3β-androstanediol, and dihydrotestosterone.[2]

Synthesis

Trilostane is prepared from testosterone in a four-step synthesis.

History

Trilostane was withdrawn from human use in the United States market in April 1994.[20][21][6] It continued to be available in the United Kingdom for use in humans under the brand name Modrenal for the treatment of Cushing's disease and breast cancer in humans, but was eventually discontinued in this country as well.[6][22][23][8]

Trilostane was approved in the United States in 2008 for the treatment of Cushing's disease (hyperadrenocorticism) in dogs under the brand name Vetoryl.[24] It was available by prescription in the United Kingdom for dogs under the Vetoryl brand name for some time before it was approved in the United States.[10] The drug is also used to treat the skin disorder Alopecia X in dogs.[20][25][26]

Trilostane was the first drug approved to treat both pituitary- and adrenal-dependent Cushing's in dogs. Only one other drug, Anipryl (veterinary brand name) selegiline, is FDA-approved to treat Cushing's disease in dogs, but only to treat uncomplicated, pituitary-dependent Cushing's.[27] The only previous treatment for the disease was the use of mitotane (brand name Lysodren) off-label.[9][28]

A number of compounding pharmacies in the United States sell trilostane for dogs. Since the United States approval of Vetoryl in December 2008,[24] compounding pharmacies are no longer able to use a bulk drug product for compounding purposes, but must prepare the compounded drug from Vetoryl.[29]

Society and culture

Generic names

Trilostane is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, and JAN.[2][3] Its developmental code name was WIN-24,540.[2][3]

Brand names

Trilostane has been marketed under a number of brand names including Desopan, Modrastane, Modrenal, Trilox, Vetoryl, Oncovet TL and Winstan.[2][3]

Availability

Trilostane is available for veterinary use in many countries throughout the world.[30]

Research

Trilostane was studied in the treatment of premenopausal breast cancer.[1]

References

- Puddefoot JR, Barker S, Vinson GP (December 2006). "Trilostane in advanced breast cancer". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 7 (17): 2413–9. doi:10.1517/14656566.7.17.2413. PMID 17109615. S2CID 23940491.

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1245–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (6 December 2012). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 281–. ISBN 978-94-011-4439-1.

- Martin Negwer (1987). Organic-chemical Drugs and Their Synonyms: (an International Survey). VCH Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89573-552-2.

5870 (6516) C20H2:NOs 13647-35-3 42,5-Epoxy-173-hydroxy-3-oxo-50-androstane-22carbonitrile = (22,42,52,173)-4,5-Epoxy-17-hydroxy-3-oxoandrostane-2-carbonitrile (e) S Desopan, Modrastane, Modrenal, Trilostane”, Trilox, Win 24 540, Winstan U Adrenocortical suppressant (steroid biosynthesis inhibitor)

- George W.A Milne (8 May 2018). Drugs: Synonyms and Properties: Synonyms and Properties. Taylor & Francis. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-1-351-78989-9.

- Tung D, Ciallella J, Hain H, Cheung PH, Saha S (December 2013). "Possible therapeutic effect of trilostane in rodent models of inflammation and nociception". Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 75: 71–6. doi:10.1016/j.curtheres.2013.09.004. PMC 3898193. PMID 24465047.

- "Cushing's Disease in Dogs Part 3: Current & Investigative Options for Therapy". Today's Veterinary Practice. 2016-02-24. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- Braddock, JA, Church, DB, Robertson, ID, Watson, ADJ (October 2003). "Trilostane treatment in dogs with pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism" (PDF). Australian Veterinary Journal. 81 (10): 600–7. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb12498.x. PMID 15080470. Retrieved 5 April 2011. (PDF)

- "Treating Cushing's Disease in Dogs". US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Vetoryl-Contraindications". NOAH Compendium of Animal Health-National Office of Animal Health UK. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Dechra US Datasheet-Vetoryl" (PDF). Dechra US. Retrieved 3 April 2011. (PDF)

- "Cushing's Disease in Dogs". NASC LIVE. Retrieved 2021-01-04.

- de Gier J; Wolthers CH; Galac S; Okkens AC; Kooistra HS (April 2011). "Effects of the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase inhibitor trilostane on luteal progesterone production in the dog". Theriogenology. 75 (7): 1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.11.041. PMID 21295836.

- Reusch, Claudia E. (2006). "Trilostane-5 Years of Clinical Experience for the Treatment of Cushing's Disease" (PDF). Ohio State University Endocrinology Symposium. pp. 17–19. Retrieved 5 April 2011. (PDF)

- Reusch, Claudia E. (2010). "Trilostane-A Review of a Success Story". World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA). Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- le Roux PA, Tregoning SK, Zinn PM, van der Spuy ZM (June 2002). "Inhibition of progesterone secretion with trilostane for mid-trimester termination of pregnancy: randomized controlled trials". Human Reproduction (Oxford, England). 17 (6): 1483–9. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.6.1483. PMID 12042266.

- Puddefoot JR, Barker S, Glover HR, Malouitre SD, Vinson GP (September 2002). "Non-competitive steroid inhibition of oestrogen receptor functions". Int. J. Cancer. 101 (1): 17–22. doi:10.1002/ijc.10547. PMID 12209583. S2CID 25779906.

- Glover, Hilary R.; Barker, Stewart; Malouitre, Sylvanie D. M.; Puddefoot, John R.; Vinson, Gavin P. (2010). "Multiple Routes to Oestrogen Antagonism". Pharmaceuticals. 3 (11): 3417–3434. doi:10.3390/ph3113417. ISSN 1424-8247.

- Takizawa I, Nishiyama T, Hara N, Hoshii T, Ishizaki F, Miyashiro Y, Takahashi K (November 2010). "Trilostane, an inhibitor of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, has an agonistic activity on androgen receptor in human prostate cancer cells". Cancer Lett. 297 (2): 226–30. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.05.015. PMID 20831980.

- Cook, Audrey K. (1 February 2008). "Trilostane: A therapeutic consideration for canine hyperadrenocorticism". DVM 360. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Trilostane consumer information". Drugs.com. 4 January 2009. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Modrenal consumer information". Drugs.com UK. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Modrenal". electronic Medicines Compendium UK. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- "Vetoryl approval information". Food and Drug Administration. 5 December 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Hillier, Andrew (2006). "Alopecia: Is an Endocrine Disorder Responsible?" (PDF). Ohio State University Endocrinology Symposium. p. 12 of 67. Retrieved 8 April 2011. (PDF)

- Cerundolo, Rosario; Lloyd, David H.; Persechino, Angelo; Evans, Helen; Cauvin, Andria (2004). "Treatment of Canine Alopecia X with trilostane" (PDF). Veterinary Dermatology. European Society of Veterinary Dermatology. 15 (5): 285–93. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3164.2004.00403.x. PMID 15500480. Retrieved 16 May 2011. (PDF)

- "Anipryl consumer information". Drugs.com Vet. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- Reine, NJ. (2007). "Medical management of pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism: mitotane versus trilostane". Clinical Tech-Small Animal Practice. 22 (1): 18–25. doi:10.1053/j.ctsap.2007.02.003. PMID 17542193.

- "VETORYL (trilostane) Capsules Letter - Pharmacy Professionals". Food and Drug Administration. 11 September 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- https://www.drugs.com/international/trilostane.html