French heraldry

French heraldry is the use of heraldic symbols in France. Although it had a considerable history, existing from the 11th century, such formality has largely died out in France, as far as regulated personal heraldry is concerned. Civic heraldry on the other hand remains a visible part of daily life.

.svg.png.webp)

The role of the herald (héraut) in France declined in the 17th century. Today the law recognises both assumed and inherited arms, considering them under law to be equivalent to a visual representation of a name, and given the same protections. However, there is no central registry of arms; in case of dispute, the individual who can prove the longest right to the blazon must be decided in court.

Many of the terms in international heraldry come from French.

Characteristics

Like the British system of heraldry, the French follow the Rule of Tinctures. This states that there are two types of Tinctures (heraldic colors): the colors Sable (black), Gueules (red), Sinople (green) and Azur (blue) and metals Or (gold or yellow) and Argent (silver or white). For sake of visibility (the whole point of the system), no Charges of a color can be used on a field of a color and no Charges of a metal can be used on a field of a metal, nor can the divisions of the field be color-on-color or metal-on-metal. Arms that do not follow the Rule of Tinctures are referred to as Armes pour enquérir (a "Coat of Arms to be investigated").

French heraldry has a set system of crown and coronets.[1] Supporters are not linked with any rank or title, unlike the coronets, and are far less common than in other forms of European heraldry, such as English heraldry.[1] Even the Royal Arms' angelic supporters are not shown in most depictions. Crests are rare in modern depictions, again in contrast to England.[1]

Napoleonic heraldry

.svg.png.webp)

Along with a new system of titles of nobility, the First French Empire also introduced a new system of heraldry.

Napoleonic heraldry was based on traditional heraldry but was characterised by a stronger sense of hierarchy. It employed a rigid system of additional marks in the shield to indicate official functions and positions. Another notable difference from traditional heraldry was the toques, which replaced coronets. The toques were surmounted by ostrich feathers: dukes had 7, counts had 5, barons had 3, and knights had 1. The number of lambrequins was also regulated: 3, 2, 1 and none respectively. As many grantees were self-made men, and the arms often alluded to their life or specific actions, many new or unusual charges were also introduced.[2]

The most characteristic mark of Napoleonic heraldry was the additional marks in the shield to indicate official functions and positions. These came in the form of quarters in various colours, and would be differenced further by marks of the specific rank or function. In this system, the arms of knights had an ordinary gules, charged with the emblem of the Legion of Honour; Barons a quarter gules in chief sinister, charged with marks of the specific rank or function; counts a quarter azure in chief dexter, charged with marks of the specific rank or function; and dukes had a chief gules semé of stars argent.[2]

The said 'marks of the specific rank or function' as used by Barons and Counts depended on the rank or function held by the individual. Military barons and counts had a sword on their quarter, members of the Conseil d'Etat had a chequy, ministers had a lion's head, prefects had a wall beneath an oak branch, mayors had a wall, landowners had a wheat stalk, judges had a balance, members of Academies had a palm, etc.[2]

A decree of 3 March 1810 states: "The name, arms and livery shall pass from the father to all sons" although the distinctive marks of title could only pass to the son who inherited it. This provision applied only to the bearers of Napoleonic titles.[2]

The Napoleonic system of heraldry did not outlast the First French Empire. The Second French Empire (1852–1870) made no effort to revive it, although the official arms of France were again those of Napoleon I.[2]

Legal status

The Commission nationale d'héraldique, an advisory body under the French Ministry of Culture, advises both public bodies and (since 2015) private individuals on heraldic issues.

French crowns and coronets

| Commune | Department Capital | Capital |

Ancien Régime

| Baron | Vidame | Vicomte (Viscount) | Comte (Count) | Comte et Pair de France (Count and Peer of France) | Marquis | Marquis et Pair de France (Marquis and Peer of France) |

|

| |||||

| Duc (Duke) | Duc et Pair de France (Dukes and Peer of France) | Prince du Sang (nobles in the descendance of a former French king) | (Petit-) Fils de France (Royal Prince, children or grandchildren of the King) | Dauphin (heir apparent), (Dauphin de Viennois) | Roi (King) |

National Emblem of France

| National Emblem of France | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | The French Republic |

| Blazon | RF, standing for République française |

| Other elements | Fasces, laurel branch, oak branch |

The current emblem of France has been a symbol of France since 1953, although it does not have any legal status as an official coat of arms. It appears on the cover of French passports and was originally adopted by the French Foreign Ministry as a symbol for use by diplomatic and consular missions in 1912 using a design drawn up by the sculptor Jules-Clément Chaplain.

In 1953, France received a request from the United Nations for a copy of the national coat of arms to be displayed alongside the coats of arms of other member states in its assembly chamber. An interministerial commission requested Robert Louis (1902–1965), heraldic artist, to produce a version of the Chaplain design. This did not, however, constitute an adoption of an official coat of arms by the Republic.

Technically speaking, it is an emblem rather than a coat of arms, since it does not respect heraldic rules—heraldry being seen as an aristocratic art, and therefore associated with the Ancien Régime. The emblem consists of:

- A wide shield with lion-head terminal bears a monogram "RF" standing for République Française (French Republic).

- A laurel branch symbolises victory of the Republic.

- An oak branch symbolises perennity or wisdom.

- The fasces is a symbol associated with justice (from Roman lictor's axes, in this case not fascism).

Fleur-de-lys

The fleur-de-lys (or fleur-de-lis, plural: fleurs-de-lis; /ˌflɜːrdəˈliː/, [ˌflœː(ʀ)dəˈlɪs] in Quebec French), translated from French as "lily flower") is a stylized design of either an iris or a lily that is now used purely decoratively as well as symbolically, or it may be "at one and the same time political, dynastic, artistic, emblematic and symbolic",[3] especially in heraldry.

While the fleur-de-lis has appeared on countless European coats of arms and flags over the centuries, it is particularly associated with the French monarchy on a historical context, and nowadays with the Spanish monarchy and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg as the only remaining monarchs of the House of Bourbon.

It is an enduring symbol of France that appears on French postage stamps but has not been adopted officially by any of the French republics.

Arms of major cities

All cities within France have coats of arms; these are often intertwined with local traditions over history.

Paris The coat of arms of the city of Paris, in its current form, dates back to 1358, when King Charles V officially installed it.[4] On the coat of arms, the represented vessel is the symbol of the powerful corporate body of the Marchands de l'eau, dating back to the Middle Ages. The city motto, "Fluctuat nec mergitur" ("It is beaten by the waves without being submerged") is equally a reference to this boat. Marseille The arms of Marseilles, passed in 1930, may be emblazoned as: Argent a cross azur. The motto of Marseille is: De grands fachs resplend la cioutat de Marseilles (Occitan), appears for the first time in 1257; La Ville de Marseille resplendit par ses hauts faits (French); Actibus immensis urbs fulget Massiliensis (Latin, used since 1691) or 'The City of Marseille shines by its deeds'. Lyon The arms of Lyon date back to the Middle Ages, when they were those of the Counts of Lyon. They constituted of a rampant (ready to pounce) argent (silver) lion on a red field, with a clearly identifiable tongue. It is around 1320 that the chief azure three fleurs de lys d'or, the upper band still present on the arms, was added to the lion symbolizing royal protection. In 1819, a sword was granted by the king in recognition of services to the king during the events of 1793. The July Monarchy of 1830 rejected the fleurs de lys and replaced them with stars that were intended to be neutral. In the early 20th century, the municipality decided to take the lion coat of arms without sword, with three fleurs de lys, the emblem of the city for six centuries. The shield reads not as a symbol, but as a riddle: the argent lion is canted: it is a pun on the city's name, "Lyon".

|

Strasbourg Strasbourg's arms are the colours of the shield of the Bishop of Strasbourg (a band of red on a white field, also considered an inversion of the arms of the diocese) at the end of a revolt of the burghers during the Middle Ages who took their independence from the teachings of the Bishop. It retains its power over the surrounding area. Nice The arms of Nice first appear in 1430.[5] The Nice is symbolized by a red eagle on white background, on top of three mountains. The arms has undergone only minor changes: the eagle become more and more stylised, a crown of a count has been added, which symbolises his dominion over the County of Nice, and the three mountains on which is based is now surrounded by a stylised sea.[5] The presence of the eagle, imperial emblem, shows that these arms are linked to savoyard power. Throughout their symbolic structure, the arms of Nice are a sign of allegiance and fidelity to the House of Savoy.[5] The combination of white and red (argent and gules) is a resumption of the Cross of Savoy.[5] The three mountains symbolise a territorial honour, without concern for geographic realism.[5] Grenoble.svg.png.webp) The coat of arms of the city of Grenoble dates back to the 14th century.[6] The three roses are symbolic representation of the three authorities who governed the city in the Middle Ages. Grenoble was placed under the authority of two rival powers, that of the bishop and of the Dauphin. In the 14th century appears a third authority, consuls, elected by the people and defenders of freedoms and exemptions granted by the two co-lords.

|

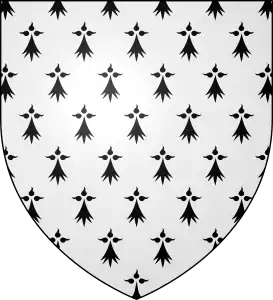

Former Regions of France

Each region of France has its own coat of arms, although usage varies:

|

|

|

|

Départments

Few départments have official arms. There may be substantial disagreements with this table.

References

- François Velde (2003-02-06). "French Heraldry: National Characteristics". Heraldica. Retrieved 2009-02-22.

- François R. Velde. Napoleonic Heraldry

- Pastoureau, Michel (1997). Heraldry: Its Origins and Meaning. 'New Horizons' series. Translated by Garvie, Francisca. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 98. ISBN 0-500-30074-7.

- Faure, Juliet (2002). L'arsenal de Paris: histoire et chroniques (in French). L'Harmattan. p. 35.

- Ralph Schor, Histoire du Comté de Nice en 100 dates, Alandis Editions, 2007, p. 22-23 (in French)

- Histoire du blason de Grenoble Archived 2008-11-12 at the Wayback Machine (in French)