History of art

The history of art focuses on objects made by humans in visual form for aesthetic purposes. Visual art can be classified in diverse ways, such as separating fine arts from applied arts; inclusively focusing on human creativity; or focusing on different media such as architecture, sculpture, painting, film, photography, and graphic arts. In recent years, technological advances have led to video art, computer art, performance art, animation, television, and videogames.

|

| History of art |

| Art history |

The history of art is often told as a chronology of masterpieces created during each civilization. It can thus be framed as a story of high culture, epitomized by the Wonders of the World. On the other hand, vernacular art expressions can also be integrated into art historical narratives, referred to as folk arts or craft. The more closely that an art historian engages with these latter forms of low culture, the more likely it is that they will identify their work as examining visual culture or material culture, or as contributing to fields related to art history, such as anthropology or archaeology. In the latter cases, art objects may be referred to as archeological artifacts.

Prehistory

.jpg.webp)

Engraved shells created by Homo erectus dating as far back as 500,000 years ago have been found, although experts disagree on whether these engravings can be properly classified as ‘art’.[1][2] A number of claims of Neanderthal art, adornment, and structures have been made, dating from around 130,000 before present and suggesting that Neanderthals may have been capable of symbolic thought,[9][10] but none of these claims are widely accepted.[11]

Paleolithic

The oldest secure human art that has been found dates to the Late Stone Age during the Upper Paleolithic, possibly from around 70,000 BC[8] but with certainty from around 40,000 BC, when the first creative works were made from shell, stone, and paint by Homo sapiens, using symbolic thought.[12] During the Upper Paleolithic (50,000–10,000 BC), humans practiced hunting and gathering and lived in caves, where cave painting was developed.[13] During the Neolithic period (10,000–3,000 BC), the production of handicrafts commenced.

The appearance of creative capacity within these early societies exemplifies an evolutionarily selective advantage for artistic individuals. Since survival is not contingent on the production of art, art-producing individuals demonstrated agency over their environments in that they had spare time to create once their essential duties, like hunting and gathering were completed.[14] These preliminary artists were rare and "highly gifted" within their communities.[15] They indicated advancements in cognition and understanding of symbolism.[15]

However, the earliest human artifacts showing evidence of workmanship with an artistic purpose are the subject of some debate. It is clear that such workmanship existed by 40,000 years ago in the Upper Paleolithic era, although it is quite possible that it began earlier.

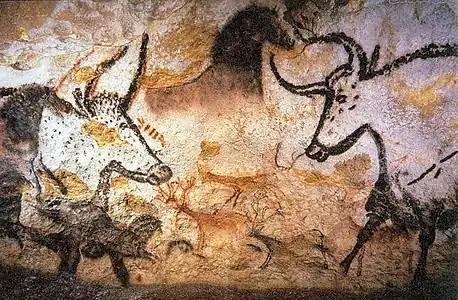

The artistic manifestations of the Upper-Paleolithic reached their peak in the Magdalenian period (±15,000–8,000 BC). This surge in creative outpourings is known as the "Upper Paleolithic Revolution" or the "Creative Explosion".[16] Surviving art from this period includes small carvings in stone or bone and cave painting. The first traces of human-made objects appeared in southern Africa, the Western Mediterranean, Central and Eastern Europe (Adriatic Sea), Siberia (Baikal Lake), India and Australia. These first traces are generally worked stone (flint, obsidian), wood or bone tools. To paint in red, iron oxide was used. Color, pattern, and visual likeness were components of Paleolithic art. Patterns used included zig-zag, criss cross, and parallel lines.[15]

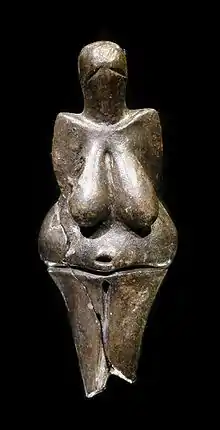

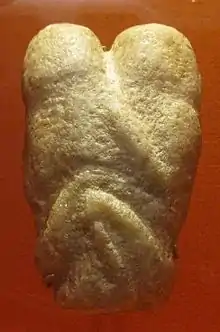

Cave paintings have been found in the Franco-Cantabrian region. There are pictures that are abstract as well as pictures that are naturalistic. Cave paintings were symbolically representative of activities that required learned participants – they were used as teaching tools and showcase an increased need for communication and specialized skills for early humans.[17] Animals were painted in the caves of Altamira, Trois Frères, Chauvet and Lascaux. Sculpture is represented by the so-called Venus figurines, feminine figures which may have been used in fertility cults, such as the Venus of Willendorf. [18] There is a theory that these figures may have been made by women as expressions of their own body.[19] Other representative works of this period are the Man from Brno[20] and Venus of Brassempouy.[21]

A function of Paleolithic art was magical, being used in rituals. Paleolithic artists were particular people, respected in the community because their artworks were linked with religious beliefs. In this way, artifacts were symbols of certain deities or spirits.[22]

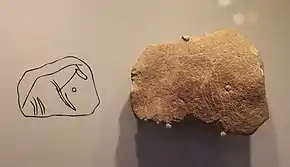

Possibly the "oldest known drawing by human hands", discovered in Blombos Cave in South Africa. Estimated to be 73,000 years old.[8]

Possibly the "oldest known drawing by human hands", discovered in Blombos Cave in South Africa. Estimated to be 73,000 years old.[8] Lion-man or Löwenmensch figurine; c. 35,000-40,000 BC (Aurignacian - Upper Paleolithic); mammoth ivory; Museum Ulm (Germany)

Lion-man or Löwenmensch figurine; c. 35,000-40,000 BC (Aurignacian - Upper Paleolithic); mammoth ivory; Museum Ulm (Germany) Vogelherd horse; c. 34,000-31,000 BC; mammoth ivory; length: 5 cm; Protohistory and Medieval Archaeology, University of Tübingen (Germany)[23]

Vogelherd horse; c. 34,000-31,000 BC; mammoth ivory; length: 5 cm; Protohistory and Medieval Archaeology, University of Tübingen (Germany)[23]

Venus of Willendorf; c. 26,000 BC (the Gravettian period); limestone with ochre coloring; Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)

Venus of Willendorf; c. 26,000 BC (the Gravettian period); limestone with ochre coloring; Naturhistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria) Venus of Dolní Věstonice; c. 26,000 BC; fired clay; height: 11.5 cm; Moravian Museum (Brno, Czech Republic)[23]

Venus of Dolní Věstonice; c. 26,000 BC; fired clay; height: 11.5 cm; Moravian Museum (Brno, Czech Republic)[23] Venus of Brassempouy; c. 23,000 BC; mammoth ivory; height: 3.5 cm; National Archaeological Museum of France (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France)[23]

Venus of Brassempouy; c. 23,000 BC; mammoth ivory; height: 3.5 cm; National Archaeological Museum of France (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France)[23] Bison Licking Insect Bite; 15,000–13,000 BC; antler; National Museum of Prehistory (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, France)

Bison Licking Insect Bite; 15,000–13,000 BC; antler; National Museum of Prehistory (Les Eyzies-de-Tayac-Sireuil, France)

Mesolithic

In Old World archaeology, Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, mesos "middle"; λίθος, lithos "stone") is the period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymously, especially for outside northern Europe, and for the corresponding period in the Levant and Caucasus. The Mesolithic has different time spans in different parts of Eurasia. It refers to the final period of hunter-gatherer cultures in Europe and West Asia, between the end of the Last Glacial Maximum and the Neolithic Revolution. In Europe it spans roughly 15,000 to 5,000 BC, in Southwest Asia (the Epipalaeolithic Near East) roughly 20,000 to 8,000 BC. The term is less used of areas further east, and not at all beyond Eurasia and North Africa.

Neolithic

The Neolithic period began about 10,000 BC. The rock art of the Iberian Mediterranean Basin—dated between the Mesolithic and Neolithic eras—contained small, schematic paintings of human figures, with notable examples in El Cogul, Valltorta, Alpera and Minateda.

Neolithic painting is similar to paintings found in northern Africa (Atlas, Sahara) and in the area of modern Zimbabwe. Neolithic painting is often schematic, made with basic strokes (men in the form of a cross and women in a triangular shape). There are also cave paintings in Pinturas River in Argentina, especially the Cueva de las Manos. In portable art, a style called Cardium pottery was produced, decorated with imprints of seashells. New materials were used in art, such as amber, crystal, and jasper. In this period, the first traces of urban planning appeared, such as the remains in Tell as-Sultan (Jericho), Jarmo (Iraq) and Çatalhöyük (Anatolia).[24] In South-Eastern Europe appeared many cultures, such as the Cucuteni-Trypillia culture (from Romania, Republic of Moldova and Ukraine), and the Hamangia culture (from Romania and Bulgaria). Other regions with many cultures are China, most notable being the Yangshao culture and the Longshan culture; and Egypt, with the Badarian, the Naqada I, II and III cultures.

Common materials of Neolithic sculptures from Anatolia, are ivory, stone, clay and bone. Many are anthropomorphic, especially female, zoomorphic ones being rare. Female figurines are both fat and slender. Both zoomorphic and anthropomorphic carvings have been discovered in Siberia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and China.[25]

The Urfa Man; from modern-day Turkey; c. 9000 BC; sandstone; height: 1.8 m; Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum (Urfa, Turkey)

The Urfa Man; from modern-day Turkey; c. 9000 BC; sandstone; height: 1.8 m; Şanlıurfa Archaeology and Mosaic Museum (Urfa, Turkey) Fragment of a bowl; by Halaf culture from Mesopotamia; 5600-5000 BC; cermaic; 8.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Fragment of a bowl; by Halaf culture from Mesopotamia; 5600-5000 BC; cermaic; 8.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City).jpg.webp) Globular jar; by Dimini culture from Greece; 5300-4800 BC; ceramic; height: 25 cm (93⁄4 in.), diameter at rim: 12 cm (43⁄4 in.); National Archaeological Museum (Athens)

Globular jar; by Dimini culture from Greece; 5300-4800 BC; ceramic; height: 25 cm (93⁄4 in.), diameter at rim: 12 cm (43⁄4 in.); National Archaeological Museum (Athens) The Thinker; by Hamangia culture from Romania; c. 5000 BC; terracotta; height: 11.5 cm (41⁄2 in.); National Museum of Romanian History (Bucharest)

The Thinker; by Hamangia culture from Romania; c. 5000 BC; terracotta; height: 11.5 cm (41⁄2 in.); National Museum of Romanian History (Bucharest) Female figure; by Vinča culture from Serbia; 4500-3500 BC; fired clay with paint; overall: 16.1 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

Female figure; by Vinča culture from Serbia; 4500-3500 BC; fired clay with paint; overall: 16.1 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US) Figurine of a bearded man; by the Naqada I culture from Egypt; 3800-3500 BC; breccia; from Upper Egypt; Musée des Confluences (Lyon, France)

Figurine of a bearded man; by the Naqada I culture from Egypt; 3800-3500 BC; breccia; from Upper Egypt; Musée des Confluences (Lyon, France) 'Flame-style' vessel; from the Jōmon period of Japan; c. 2750 BC; earthenware with carved and applied decoration; height: 61 cm, diameter: 55.8 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

'Flame-style' vessel; from the Jōmon period of Japan; c. 2750 BC; earthenware with carved and applied decoration; height: 61 cm, diameter: 55.8 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US) Dotted pottery pot, semi-mountain type; by the Yangshao culture from China; 2700–2300 BC; Gansu Provincial Museum (Lanzhou; China)

Dotted pottery pot, semi-mountain type; by the Yangshao culture from China; 2700–2300 BC; Gansu Provincial Museum (Lanzhou; China)

Metal Age

The last prehistoric phase is the Metal Age (or Three-age system), during which the use of copper, bronze and iron transformed ancient societies. When humans could smelt and forge, metal implements could be used to make new tools, weapons, and art.

In the Chalcolithic (Copper Age), megaliths emerged. Examples include the dolmen, menhir and the English cromlech, as can be seen in the complexes at Newgrange and Stonehenge.[26] In Spain, the Los Millares culture, which was characterized by the Beaker culture, was formed. In Malta, the temple complexes consist of Ħaġar Qim, Mnajdra, Tarxien and Ġgantija were built. In the Balearic Islands, notable megalithic cultures were developed, with different types of monuments: the naveta, a tomb shaped like a truncated pyramid, with an elongated burial chamber; the taula, two large stones, one put vertically and the other horizontally above each other; and the talaiot, a tower with a covered chamber and a false dome.[27]

In the Iron Age, the cultures of Hallstatt (Austria) and La Tène (Switzerland) emerged in Europe. The former was developed between the 7th and 5th century BC, featured by the necropoleis with tumular tombs and a wooden burial chamber in the form of a house, often accompanied by a four-wheeled cart. The pottery was polychromic, with geometric decorations and applications of metallic ornaments. La Tène was developed between the 5th and 4th century BC, and is more popularly known as early Celtic art. It produced many iron objects such as swords and spears, which have not survived well to the 2000s due to rust.

The Bronze Age refers to the period when bronze was the best material available. Bronze was used for highly decorated shields, fibulas, and other objects, with different stages of evolution of the style. Decoration was influenced by Greek, Etruscan and Scythian art.[28]

Antiquity

In the first period of recorded history, art coincided with writing. The great civilizations of the Near East: Egypt and Mesopotamia arose. Globally, during this period the first great cities appeared near major rivers: the Nile, Tigris and Euphrates, Indus and Yellow River.

One of the great advances of this period was writing, which was developed from the tradition of communication using pictures. The first form of writing were the Jiahu symbols from Neolithic China, but the first true writing was cuneiform script, which emerged in Mesopotamia c. 3500 BC, written on clay tablets. It was based on pictographic and ideographic elements, while later Sumerians developed syllables for writing, reflecting the phonology and syntax of the Sumerian language. In Egypt hieroglyphic writing was developed using pictures as well, appearing on art such as the Narmer Palette (3,100 BC). The Indus Valley Civilization sculpted seals with short texts and decorated with representations of animals and people. Meanwhile, the Olmecs sculpted colossal heads and decorated other sculptures with their own hieroglyphs. In these times, writing was accessible only for the elites.

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamian art was developed in the area between Tigris and Euphrates Rivers in modern-day Syria and Iraq, where since the 4th millennium BC many different cultures existed such as Sumer, Akkad, Amorite and Chaldea. Mesopotamian architecture was characterized by the use of bricks, lintels, and cone mosaic. Notable examples are the ziggurats, large temples in the form of step pyramids. The tomb was a chamber covered with a false dome, as in some examples found at Ur. There were also palaces walled with a terrace in the form of a ziggurat, where gardens were an important feature. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Relief sculpture was developed in wood and stone. Sculpture depicted religious, military, and hunting scenes, including both human and animal figures. In the Sumerian period, small statues of people were produced. These statues had an angular form and were produced from colored stone. The figures typically had bald head with hands folded on the chest. In the Akkadian period, statues depicted figures with long hair and beards, such as the stele of Naram-Sin. In the Amorite period (or Neosumerian), statues represented kings from Gudea of Lagash, with their mantles and a turbans on their heads, and their hands on their chests. During Babylonian rule, the stele of Hammurabi was important, as it depicted the great king Hammurabi above a written copy of the laws that he introduced. Assyrian sculpture is notable for its anthropomorphism of cattle and the winged genie, which is depicted flying in many reliefs depicting war and hunting scenes, such as in the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.[29]

Standing male worshipper, one of the twelve statues in the Tell Asmar Hoard; 2900-2600 BC; gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone and bitumen; 29.5 × 12.9 × 10 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Standing male worshipper, one of the twelve statues in the Tell Asmar Hoard; 2900-2600 BC; gypsum alabaster, shell, black limestone and bitumen; 29.5 × 12.9 × 10 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Sumerian Statues of worshippers (males and females); 2800-2400 BC (Early Dynastic period); National Museum of Iraq (Baghdad)

Sumerian Statues of worshippers (males and females); 2800-2400 BC (Early Dynastic period); National Museum of Iraq (Baghdad) Bull's head ornament from a lyre; 2600-2350 BC; bronze inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli; height: 13.3 cm, width: 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bull's head ornament from a lyre; 2600-2350 BC; bronze inlaid with shell and lapis lazuli; height: 13.3 cm, width: 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art A Ram in a Thicket; 2600–2400 BC; gold, copper, shell, lapis lazuli and limestone; height: 45.7 cm (1 ft 6 in.); British Museum (London)

A Ram in a Thicket; 2600–2400 BC; gold, copper, shell, lapis lazuli and limestone; height: 45.7 cm (1 ft 6 in.); British Museum (London)_(2).jpg.webp) The Standard of Ur; 1600–1400 BC (the Early Dynastic Period III); shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli on wood; height: 21.7 cm, length: 50.4 cm; discovered at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq); British Museum

The Standard of Ur; 1600–1400 BC (the Early Dynastic Period III); shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli on wood; height: 21.7 cm, length: 50.4 cm; discovered at the Royal Cemetery at Ur (Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq); British Museum The Statue of Ebih-Il; c. 2400 BC; gypsum, schist, shells and lapis lazuli; height: 52.5 cm; Louvre (Paris)

The Statue of Ebih-Il; c. 2400 BC; gypsum, schist, shells and lapis lazuli; height: 52.5 cm; Louvre (Paris) Seal of Hash-hamer, showing enthroned king Ur-Nammu, with modern impression; circa 2100 BC; greenstone; height: 5.3 cm; British Museum (London)

Seal of Hash-hamer, showing enthroned king Ur-Nammu, with modern impression; circa 2100 BC; greenstone; height: 5.3 cm; British Museum (London).jpg.webp) Assyrian relief with a winged genie with bucket and cone; 713-706 BC; height: 3.3 m, width: 2.1 m; Louvre

Assyrian relief with a winged genie with bucket and cone; 713-706 BC; height: 3.3 m, width: 2.1 m; Louvre

Egypt

One of the first great civilizations arose in Egypt, which had elaborate and complex works of art produced by professional artists and craftspeople. Egypt's art was religious and symbolic. Given that the culture had a highly centralized power structure and hierarchy, a great deal of art was created to honour the pharaoh, including great monuments. Egyptian art and culture emphasized the religious concept of immortality. Later Egyptian art includes Coptic and Byzantine art.

The architecture is characterized by monumental structures, built with large stone blocks, lintels, and solid columns. Funerary monuments included mastaba, tombs of rectangular form; pyramids, which included step pyramids (Saqqarah) or smooth-sided pyramids (Giza); and the hypogeum, underground tombs (Valley of the Kings). Other great buildings were the temple, which tended to be monumental complexes preceded by an avenue of sphinxes and obelisks. Temples used pylons and trapezoid walls with hypaethros and hypostyle halls and shrines. The temples of Karnak, Luxor, Philae and Edfu are good examples. Another type of temple is the rock temple, in the form of a hypogeum, found in Abu Simbel and Deir el-Bahari.

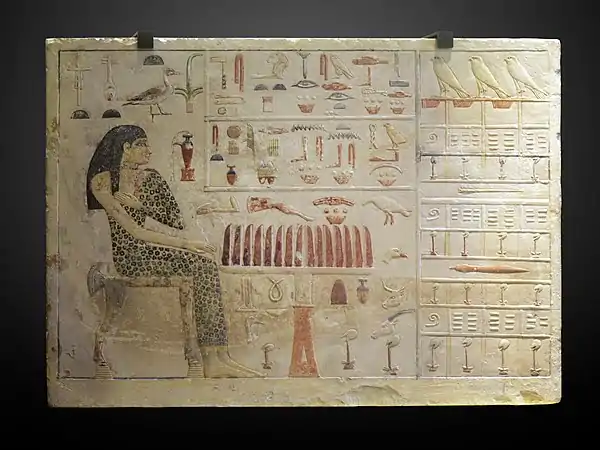

Painting of the Egyptian era used a juxtaposition of overlapping planes. The images were represented hierarchically, i.e., the Pharaoh is larger than the common subjects or enemies depicted at his side. Egyptians painted the outline of the head and limbs in profile, while the torso, hands, and eyes were painted from the front. Applied arts were developed in Egypt, in particular woodwork and metalwork. There are superb examples such as cedar furniture inlaid with ebony and ivory which can be seen in the tombs at the Egyptian Museum. Other examples include the pieces found in Tutankhamun's tomb, which are of great artistic value.[30]

Stele of Princess Nefertiabet eating; 2589–2566 BC; limestone & paint; height: 37.7 cm, length: 52.5 cm, depth: 8.3 cm; from Giza; Louvre (Paris)

Stele of Princess Nefertiabet eating; 2589–2566 BC; limestone & paint; height: 37.7 cm, length: 52.5 cm, depth: 8.3 cm; from Giza; Louvre (Paris) Pectoral and necklace of Princess Sithathoriunet; 1887–1813 BC; gold, carnelian, lapis lazuli, turquoise, garnet & feldspar; height of the pectoral: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Pectoral and necklace of Princess Sithathoriunet; 1887–1813 BC; gold, carnelian, lapis lazuli, turquoise, garnet & feldspar; height of the pectoral: 4.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City).jpg.webp) Ushabti of Amenhotep II; 1427–1400 BC; serpentine; 29 × 9 × 0.65 cm, 1.4 kg; British Museum (London)

Ushabti of Amenhotep II; 1427–1400 BC; serpentine; 29 × 9 × 0.65 cm, 1.4 kg; British Museum (London) Gaming board inscribed for Amenhotep III with separate sliding drawer; 1390–1353 BC; glazed faience; 5.5 × 7.7 × 21 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City)

Gaming board inscribed for Amenhotep III with separate sliding drawer; 1390–1353 BC; glazed faience; 5.5 × 7.7 × 21 cm; Brooklyn Museum (New York City) Statuette of the lady Tiye; 1390-1349 BC; wood, carnelian, gold, glass, Egyptian blue and paint; height: 24 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Statuette of the lady Tiye; 1390-1349 BC; wood, carnelian, gold, glass, Egyptian blue and paint; height: 24 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art The Mask of Tutankhamun; c. 1327 BC; gold, glass and semi-precious stones; height: 54 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo)

The Mask of Tutankhamun; c. 1327 BC; gold, glass and semi-precious stones; height: 54 cm; Egyptian Museum (Cairo).jpg.webp) Relief of the royal family: Akhenaten, Nefertiti and the three daughters; 1352–1336 BC; painted limestone; 25 × 20 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

Relief of the royal family: Akhenaten, Nefertiti and the three daughters; 1352–1336 BC; painted limestone; 25 × 20 cm; Egyptian Museum of Berlin (Germany)

The entrance of the Great Temple of the Abu Simbel temples, founded around 1264 BC

The entrance of the Great Temple of the Abu Simbel temples, founded around 1264 BC

Illustration of various types of capitals, drawn by the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius

Illustration of various types of capitals, drawn by the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius

Indus Valley Civilization (Harappan)

Discovered long after the contemporary civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization or Harappan civilization (c. 2400–1900 BC) is now recognized as extraordinally advanced, comparable in many ways with those cultures.

Various sculptures, seals, bronze vessels pottery, gold jewellery, and anatomically detailed figurines in terracotta, bronze, and steatite have been found at excavation sites.[31]

A number of gold, terracotta and stone figurines of girls in dancing poses reveal the presence of some dance form. These terracotta figurines included cows, bears, monkeys, and dogs. The animal depicted on a majority of seals at sites of the mature period has not been clearly identified. Part bull, part zebra, with a majestic horn, it has been a source of speculation. As yet, there is insufficient evidence to substantiate claims that the image had religious or cultic significance, but the prevalence of the image raises the question of whether or not the animals in images of the civilisation are religious symbols.[32]

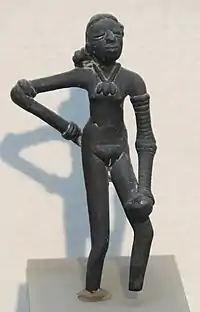

Realistic statuettes have been found in the site in the Indus Valley Civilization. One of them is the famous bronze statuette of a slender-limbed Dancing Girl adorned with bangles, found in Mohenjo-daro. Two other realistic statuettes have been found in Harappa in proper stratified excavations, which display near-Classical treatment of the human shape: the statuette of a dancer who seems to be male, and a red jasper male torso, both now in the Delhi National Museum. Archaeologist Sir John Marshall reacted with surprise when he saw these two statuettes from Harappa:[33]

When I first saw them I found it difficult to believe that they were prehistoric; they seemed to completely upset all established ideas about early art, and culture. Modeling such as this was unknown in the ancient world up to the Hellenistic age of Greece, and I thought, therefore, that some mistake must surely have been made; that these figures had found their way into levels some 3000 years older than those to which they properly belonged ... Now, in these statuettes, it is just this anatomical truth which is so startling; that makes us wonder whether, in this all-important matter, Greek artistry could possibly have been anticipated by the sculptors of a far-off age on the banks of the Indus.[33]

These statuettes remain controversial, due to their advanced techniques. Regarding the red jasper torso, the discoverer, Vats, claims a Harappan date, but Marshall considered this statuette is probably historical, dating to the Gupta period, comparing it to the much later Lohanipur torso.[34][35] A second rather similar grey stone statuette of a dancing male was also found about 150 meters away in a secure Mature Harappan stratum. Overall, anthropologist Gregory Possehl tends to consider that these statuettes probably form the pinnacle of Indus art during the Mature Harappan period.[34]

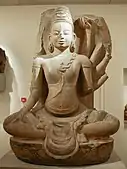

Seals have been found at Mohenjo-daro depicting a figure standing on its head, and another sitting cross-legged in what some call a yoga-like pose such as the so-called Pashupati. This figure has been variously identified. Sir John Marshall identified a resemblance to the Hindu god, Shiva.[36] If this can be validated, it would be evidence that some aspects of Hinduism predate the earliest texts, the Veda.

Ceremonial vessel; 2600-2450 BC; terracotta with black paint; 49.53 × 25.4 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Ceremonial vessel; 2600-2450 BC; terracotta with black paint; 49.53 × 25.4 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)_MET_DP23101_(cropped).jpg.webp) Stamp seal and modern impression: unicorn and incense burner (?); 2600-1900 BC; burnt steatite; 3.8 × 3.8 × 1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Stamp seal and modern impression: unicorn and incense burner (?); 2600-1900 BC; burnt steatite; 3.8 × 3.8 × 1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) The Priest-King; 2400–1900 BC; low fired steatite; height: 17.5 cm; National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi)

The Priest-King; 2400–1900 BC; low fired steatite; height: 17.5 cm; National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi)

Ancient China

During the Chinese Bronze Age (the Shang and Zhou dynasties) court intercessions and communication with the spirit world were conducted by a shaman (possibly the king himself). In the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1050 BC), the supreme deity was Shangdi, but aristocratic families preferred to contact the spirits of their ancestors. They prepared elaborate banquets of food and drink for them, heated and served in bronze ritual vessels. Bronze vessels were used in religious rituals to cement Dhang authority, and when the Shang capital fell, around 1050 BC, its conquerors, the Zhou (c. 1050–156 BC), continued to use these containers in religious rituals, but principally for food rather than drink. The Shang court had been accused of excessive drunkenness, and the Zhou, promoting the imperial Tian ("Heaven") as the prime spiritual force, rather than ancestors, limited wine in religious rites, in favour of food. The use of ritual bronzes continued into the early Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD).

One of the most commonly used motifs was the taotie, a stylized face divided centrally into 2 almost mirror-image halves, with nostrils, eyes, eyebrows, jaws, cheeks and horns, surrounded by incised patterns. Whether taotie represented real, mythological or wholly imaginary creatures cannot be determined.

The enigmatic bronzes of Sanxingdui, near Guanghan (in Sichuan province), are evidence for a mysterious sacrificial religious system unlike anything elsewhere in ancient China and quite different from the art of the contemporaneous Shang at Anyang. Excavations at Sanxingdui since 1986 have revealed 4 pits containing artefacts of bronze, jade and gold. There was found a great bronze statue of a human figure which stands on a plinth decorated with abstract elephant heads. Besides the standing figure, the first 2 pits contained over 50 bronze heads, some wearing headgear and 3 with a frontal covering of gold leaf.

Standing statue of a king and shaman leader; c. 1200–1000 BC; probably bronze; total height: 2.62 m; Sanxingdui Museum (Guanghan, Sichuan province, China)

Standing statue of a king and shaman leader; c. 1200–1000 BC; probably bronze; total height: 2.62 m; Sanxingdui Museum (Guanghan, Sichuan province, China) Houmuwu ding, the largest ancient bronze ever found; 1300–1046 BC; bronze; National Museum of China (Beijing)

Houmuwu ding, the largest ancient bronze ever found; 1300–1046 BC; bronze; National Museum of China (Beijing) Altar set; late 11th century BC; bronze; overall (table): height: 18.1 cm, width: 46.4 cm, depth: 89.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Altar set; late 11th century BC; bronze; overall (table): height: 18.1 cm, width: 46.4 cm, depth: 89.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City).jpg.webp) One of the warriors of the Terracotta Army, a famous collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China

One of the warriors of the Terracotta Army, a famous collection of terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China

Greek

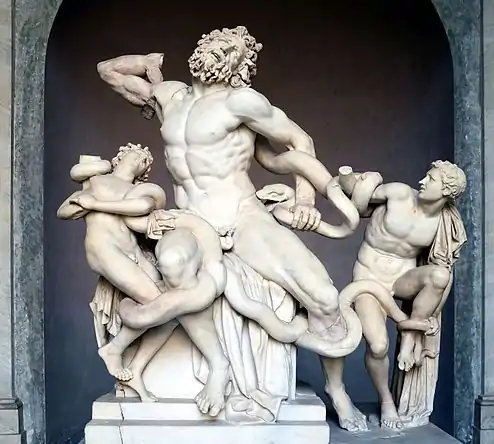

Even in antiquity, the arts of Greece were recognised by other cultures as pre-eminent. The Latin poet Horace, writing in the age of Roman emperor Augustus (1st century BC to 1st century AD), famously remarked that although conquered on the battlefield, "captive Greece overcame its savage conqueror and brought the arts to rustic Rome." The power of Greek art lies in its representation of the human figure and its focus on human beings and the anthropomorphic gods as chief subjects. During the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries BC), realism and idealism were delicately balanced. In comparison, work of the earlier Geometric (9th to 8th centuries BC) and Archaic (7th to 6th centuries BC) ages sometimes appears primitive, but these artists had different goals: naturalistic representation was not necessarily their aim. Roman art lover collected ancient Greek originals, Roman replicas of Greek art, or newly created paintings and sculptures fashioned in a variety of Greek styles, thus preserving for posterity works of art otherwise lost. Wall and panel paintings, sculptures and mosaics decorated public spaces and well-to-do private homes. Greek imagery also appeared on Roman jewellery, vessels of gold, silver, bronze and terracotta, and even on weapons and commercial weights. Since the Renaissance, the arts of ancient Greece, transmitted through the Roman Empire, have served as the foundation of Western art.[37]

Pre-Classical

Greek and Etruscan artists built on the artistic foundations of Egypt, further developing the arts of sculpture, painting, architecture, and ceramics. Greek art started as smaller and simpler than Egyptian art, and the influence of Egyptian art on the Greeks started in the Cycladic islands between 3300 and 3200 BC. Cycladic statues were simple, lacking facial features except for the nose.

The harpist, the most iconic Cycladic artwork; 2750-2200 BC; marble; height: 29.5 cm; said to be from Keros (the Cyclades); National Archaeological Museum (Athens)

The harpist, the most iconic Cycladic artwork; 2750-2200 BC; marble; height: 29.5 cm; said to be from Keros (the Cyclades); National Archaeological Museum (Athens) Female Cycladic figurine; 2700–2600 BC; marble; height: 37.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Female Cycladic figurine; 2700–2600 BC; marble; height: 37.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Kamares ware beaked jug; 1850-1675 BC; ceramic; height: 27 cm; from Phaistos (Crete, Greece); Heraklion Archaeological Museum (Greece)

Kamares ware beaked jug; 1850-1675 BC; ceramic; height: 27 cm; from Phaistos (Crete, Greece); Heraklion Archaeological Museum (Greece) The Mask of Agamemnon, the most iconic Mycenaean artwork; 1675-1600 BC; gold; height: 25 cm, width: 27 cm, weight: 169 g; National Archaeological Museum (Athens)

The Mask of Agamemnon, the most iconic Mycenaean artwork; 1675-1600 BC; gold; height: 25 cm, width: 27 cm, weight: 169 g; National Archaeological Museum (Athens)_-_Heraklion_AM_-_01.jpg.webp) The Minoan fresco named the Bull-Leaping Fresco; 1675-1460 BC; lime plaster; height: 0.8 m, width: 1 m; from the palace at Knossos (Crete); Heraklion Archaeological Museum

The Minoan fresco named the Bull-Leaping Fresco; 1675-1460 BC; lime plaster; height: 0.8 m, width: 1 m; from the palace at Knossos (Crete); Heraklion Archaeological Museum.JPG.webp) Minoan snake goddess; 1460-1410 BC (from the Minoan Neo-palatial Period); faience; height: 29.5 cm; from the Temple Repository at Knossos; Heraklion Archaeological Museum

Minoan snake goddess; 1460-1410 BC (from the Minoan Neo-palatial Period); faience; height: 29.5 cm; from the Temple Repository at Knossos; Heraklion Archaeological Museum Three Mycenaean female figures; 1400-1300 BC; terracotta; heights: 10.8 cm, 10.8 cm and 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Three Mycenaean female figures; 1400-1300 BC; terracotta; heights: 10.8 cm, 10.8 cm and 10.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Mycenaean necklace; 1400-1050 BC; gilded terracotta; diameter of the rosettes: 2.7 cm, with variations of circa 0.1 cm, length of the pendant 3.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mycenaean necklace; 1400-1050 BC; gilded terracotta; diameter of the rosettes: 2.7 cm, with variations of circa 0.1 cm, length of the pendant 3.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Geometric

After the collapse of Mycenaean society, a style of Greek art emerged that illustrates clearly the break in culture and art between the Bronze Age and the ensuing Iron Age. The Protogeometric (circa 1050–900 BC) and succeeding Geometric (circa 900–700 BC) styles are characterised by their stark simplicity of decoration, as older floral and marine motifs were replaced with abstract patterns. In the new styles, pattern was rigorously applied to shape, each decorative element subordinate to but enhancing the whole. Surfaces were adorned with triangles, lines and semicircles, and concentric circles made with a multiple brush attached to a compass. The meander (Greek key) pattern was popular, as were chequerboards, diamonds, chevrons and stars. Geometric figures, whether painted or sculpted, conform to an abstract aesthetic. Although they have recognisable forms, people and animals are composed of a combination of circles, triangles and rectangles, rather than organic, realistic shapes.[38]

Krater with lid surmounted by a small hydria; 750-740 BC; terracotta; height: 114.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Krater with lid surmounted by a small hydria; 750-740 BC; terracotta; height: 114.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Krater; 750-735 BC; terracotta; height: 108.3 cm, diameter: 72.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Krater; 750-735 BC; terracotta; height: 108.3 cm, diameter: 72.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Statuette of a horse; 750-700 BC; bronze; overall: 11.5 × 10 × 2.6 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US)

Statuette of a horse; 750-700 BC; bronze; overall: 11.5 × 10 × 2.6 cm; Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, US) Statuette of a horse; circa 740 BC; bronze; height: 6.5 cm; Louvre

Statuette of a horse; circa 740 BC; bronze; height: 6.5 cm; Louvre

Classical and Hellenistic

The human figure remained the most significant image in Greek sculpture of the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries BC). Artists strove to balance idealised bodily beauty and increasingly realistic anatomy, imitating nature by precisely rendering the ligaments, musculature and curves of the human form.[39]

The Euphiletos Painter Panathenaic prize amphora; circa 530 BC; painted terracotta; height: 62.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

The Euphiletos Painter Panathenaic prize amphora; circa 530 BC; painted terracotta; height: 62.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

.jpg.webp) The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, the most iconic Doric Greek temple built of marble and limestone between circa 460-406 BC, dedicated to the goddess Athena[40]

The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, the most iconic Doric Greek temple built of marble and limestone between circa 460-406 BC, dedicated to the goddess Athena[40] Mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman; mid-5th century BC; bronze; height: 40.41 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mirror with a support in the form of a draped woman; mid-5th century BC; bronze; height: 40.41 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Grave relief of Thraseas and Euandria; 375-350 BC; Pentelic marble; height: 160 cm, width: 91 cm; Pergamon Museum (Berlin)

The Grave relief of Thraseas and Euandria; 375-350 BC; Pentelic marble; height: 160 cm, width: 91 cm; Pergamon Museum (Berlin) Volute krater; 320-310 BC; ceramic; height: 1.1 m; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

Volute krater; 320-310 BC; ceramic; height: 1.1 m; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US) Statuette of a draped woman; 2nd century BC; terracotta; height: 29.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Statuette of a draped woman; 2nd century BC; terracotta; height: 29.2 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mosaic which represents the Epiphany of Dionysus; 2nd century AD; from the Villa of Dionysus (Dion, Greece); Archeological Museum of Dion

Mosaic which represents the Epiphany of Dionysus; 2nd century AD; from the Villa of Dionysus (Dion, Greece); Archeological Museum of Dion Illustrations of examples of ancient Greek ornaments and patterns, drawn in 1874

Illustrations of examples of ancient Greek ornaments and patterns, drawn in 1874

Phoenician

Phoenician art lacks unique characteristics that might distinguish it from its contemporaries. This is due to its being highly influenced by foreign artistic cultures: primarily Egypt, Greece and Assyria. Phoenicians who were taught on the banks of the Nile and the Euphrates gained a wide artistic experience and finally came to create their own art, which was an amalgam of foreign models and perspectives.[41] In an article from The New York Times published on January 5, 1879, Phoenician art was described by the following:

He entered into other men's labors and made most of his heritage. The Sphinx of Egypt became Asiatic, and its new form was transplanted to Nineveh on the one side and to Greece on the other. The rosettes and other patterns of the Babylonian cylinders were introduced into the handiwork of Phoenicia, and so passed on to the West, while the hero of the ancient Chaldean epic became first the Tyrian Melkarth, and then the Herakles of Hellas.

Decorative plaque which depicts a fighting of man and griffin; 900–800 BC; Nimrud ivories; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US)

Decorative plaque which depicts a fighting of man and griffin; 900–800 BC; Nimrud ivories; Cleveland Museum of Art (Ohio, US).jpg.webp) Mask; 4th century BC; found in a grave at San Sperate (Sardinia, Italy); Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari (Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy)

Mask; 4th century BC; found in a grave at San Sperate (Sardinia, Italy); Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Cagliari (Cagliari, Sardinia, Italy) Face bead; mid-4th–3rd century BC; glass; height: 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Face bead; mid-4th–3rd century BC; glass; height: 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Earring from a pair, each with four relief faces; late 4th–3rd century BC; gold; overall: 3.5 × 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Earring from a pair, each with four relief faces; late 4th–3rd century BC; gold; overall: 3.5 × 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Etruscan

Etruscan art was produced by the Etruscan civilization in central Italy between the 9th and 2nd centuries BC. From around 600 BC it was heavily influenced by Greek art, which was imported by the Etruscans, but always retained distinct characteristics. Particularly strong in this tradition were figurative sculpture in terracotta (especially life-size on sarcophagi or temples), wall-painting and metalworking especially in bronze. Jewellery and engraved gems of high quality were produced.[42]

Etruscan sculpture in cast bronze was famous and widely exported, but relatively few large examples have survived (the material was too valuable, and recycled later). In contrast to terracotta and bronze, there was relatively little Etruscan sculpture in stone, despite the Etruscans controlling fine sources of marble, including Carrara marble, which seems not to have been exploited until the Romans.

The great majority of survivals came from tombs, which were typically crammed with sarcophagi and grave goods, and terracotta fragments of architectural sculpture, mostly around temples. Tombs have produced all the fresco wall-paintings, which show scenes of feasting and some narrative mythological subjects.

The Monteleone chariot; 2nd quarter of the 6th century BC; bronze and ivory; total height: 130.9 cm, length of the pole: 209 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

The Monteleone chariot; 2nd quarter of the 6th century BC; bronze and ivory; total height: 130.9 cm, length of the pole: 209 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

_--_Getty_Villa_-_Collection.jpg.webp) Water jar with Herakles and the Hydra; circa 525 BC; black-figure pottery; height: 44.5 cm, diameter: 33.8 cm; Getty Villa (California, US)

Water jar with Herakles and the Hydra; circa 525 BC; black-figure pottery; height: 44.5 cm, diameter: 33.8 cm; Getty Villa (California, US)

Fresco with dancers and musicians; c. 475 BC; fresco secco; height (of the wall); 1.7 m; Tomb of the Leopards (Monterozzi necropolis, Lazio, Italy)

Fresco with dancers and musicians; c. 475 BC; fresco secco; height (of the wall); 1.7 m; Tomb of the Leopards (Monterozzi necropolis, Lazio, Italy) The Vulci set of jewelry; early 5th century; gold, glass, rock crystal, agate and carnelian; various dimensions; Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Vulci set of jewelry; early 5th century; gold, glass, rock crystal, agate and carnelian; various dimensions; Metropolitan Museum of Art_MET_DP21045.jpg.webp) Tripod base for a thymiaterion (incense burner); 475-450 BC; bronze; height: 11 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Tripod base for a thymiaterion (incense burner); 475-450 BC; bronze; height: 11 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Earring in the form of a dolphin; 5th century BC; gold; 2.1 × 1.4 × 4.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Earring in the form of a dolphin; 5th century BC; gold; 2.1 × 1.4 × 4.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Dacian

Dacian art is the art associated with the peoples known as Dacians or North Thracians (Getae); The Dacians created an art style in which the influences of Scythians and the Greeks can be seen. They were highly skilled in gold and silver working and in pottery making. Pottery was white with red decorations in floral, geometric, and stylized animal motifs. Similar decorations were worked in metal, especially the figure of a horse, which was common on Dacian coins.[43] Today, a big collection of Dacic masterpieces is in the National Museum of Romanian History (Bucharest), one of the most famous being the Helmet of Coțofenești.

The Geto-Dacians lived in a very large territory, stretching from the Balkans to the northern Carpathians and from the Black Sea and the river Tyras to the Tisa plain, sometimes even to the Middle Danube.[44] Between 15th–12th century, the Dacian-Getae culture was influenced by the Bronze Age Tumulus-Urnfield warriors.[45]

Bracelet; 5th-4th century BC; gold; National History Museum of Romania (Bucharest, Romania)

Bracelet; 5th-4th century BC; gold; National History Museum of Romania (Bucharest, Romania) The Helmet of Coțofenești; 4th century BC; National History Museum of Romania

The Helmet of Coțofenești; 4th century BC; National History Museum of Romania Rhyton; 4th-3rd century BC; possibly made of gold and silver; National History Museum of Romania

Rhyton; 4th-3rd century BC; possibly made of gold and silver; National History Museum of Romania The Helmet of Peretu; 310-290 BC; gilded silver; from Peretu (Teleorman County, Romania); National History Museum of Romania

The Helmet of Peretu; 310-290 BC; gilded silver; from Peretu (Teleorman County, Romania); National History Museum of Romania

Pre-Roman Iberian

Pre-Roman Iberian art refers to the styles developed by the Iberians from the Bronze Age up to the Roman conquest. For this reason it is sometimes described as "Iberian art".

Almost all extant works of Iberian sculpture visibly reflect Greek and Phoenician influences, and Assyrian, Hittite and Egyptian influences from which those derived; yet they have their own unique character. Within this complex stylistic heritage, individual works can be placed within a spectrum of influences – some of more obvious Phoenician derivation, and some so similar to Greek works that they could have been directly imported from that region. Overall the degree of influence is correlated to the work's region of origin, and hence they are classified into groups on that basis.

.jpg.webp) The Bicha of Balazote; 6th century BC; carved of two limestone blocks; height: 73 cm; National Archaeological Museum of Spain (Madrid)

The Bicha of Balazote; 6th century BC; carved of two limestone blocks; height: 73 cm; National Archaeological Museum of Spain (Madrid).jpg.webp) The Lady of Elche; c. 450 BC; limestone; National Archaeological Museum of Spain

The Lady of Elche; c. 450 BC; limestone; National Archaeological Museum of Spain_(2).jpg.webp) The Lion from Nueva Carteya; 4th century BC; limestone; height: 60 cm; Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Córdoba (Spain)

The Lion from Nueva Carteya; 4th century BC; limestone; height: 60 cm; Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Córdoba (Spain) Figurine of a standing male; 3rd-2nd century BC; cast bronze; height: 6.8 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Figurine of a standing male; 3rd-2nd century BC; cast bronze; height: 6.8 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Hittite

Hittite art was produced by the Hittite civilization in ancient Anatolia, in modern-day Turkey, and also stretching into Syria during the second millennium BC from the nineteenth century up until the twelfth century BC. This period falls under the Anatolian Bronze Age. It is characterized by a long tradition of canonized images and motifs rearranged, while still being recognizable, by artists to convey meaning to a largely illiterate population:

Owing to the limited vocabulary of figural types [and motifs], invention for the Hittite artist usually was a matter of combining and manipulating the units to form more complex compositions.[46]

Many of these recurring images revolve around the depiction of Hittite deities and ritual practices. There is also a prevalence of hunting scenes in Hittite relief and representational animal forms. Much of the art comes from settlements like Alaca Höyük, or the Hittite capital of Hattusa near modern-day Boğazkale. Scholars do have difficulty dating a large portion of Hittite art, citing the fact that there is a lack of inscription and much of the found material, especially from burial sites, was moved from their original locations and distributed among museums during the nineteenth century.

.jpg.webp) Drinking cup in the shape of a fist; 1400-1380 BC; silver; from Central Turkey; Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, US)

Drinking cup in the shape of a fist; 1400-1380 BC; silver; from Central Turkey; Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, US) Vessel terminating in the forepart of a stag; c. 14th–13th century BC; silver with gold inlay; height: 18 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Vessel terminating in the forepart of a stag; c. 14th–13th century BC; silver with gold inlay; height: 18 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Seal of Tarkasnawa, King of Mira; circa 1220 BC; silver; height: 1 cm, diameter: 4.2 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US)

Seal of Tarkasnawa, King of Mira; circa 1220 BC; silver; height: 1 cm, diameter: 4.2 cm; Walters Art Museum (Baltimore, US) Three reliefs from the Adana Archaeology Museum (Turkey)

Three reliefs from the Adana Archaeology Museum (Turkey)

Bactrian

The Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (a.k.a. the Oxus civilisation) is the modern archaeological designation for a Bronze Age civilization of Central Asia, dated to c. 2300–1700 BC, in present-day northern Afghanistan, eastern Turkmenistan, southern Uzbekistan and western Tajikistan, centred on the upper Amu Darya (Oxus River). Its sites were discovered and named by the Soviet archaeologist Viktor Sarianidi (1976). Monumental urban centers, palaces and cultic buildings were uncovered, notably at Gonur-depe in Turkmenistan.

BMAC materials have been found in the Indus Valley Civilisation, on the Iranian Plateau, and in the Persian Gulf.[47] Finds within BMAC sites provide further evidence of trade and cultural contacts. They include an Elamite-type cylinder seal and a Harappan seal stamped with an elephant and Indus script found at Gonur-depe.[48] The relationship between Altyn-Depe and the Indus Valley seems to have been particularly strong. Among the finds there were two Harappan seals and ivory objects. The Harappan settlement of Shortugai in Northern Afghanistan on the banks of the Amu Darya probably served as a trading station.[49]

A famous type of Bactrian artworks are the "Bactrian princesses" (a.k.a. "Oxus ladies"). Wearing large stylized dresses with puffed sleeves, as well as headdresses that merge with the hair, they embody the ranking goddess, character of the central Asian mythology that plays a regulatory role, pacifying the untamed forces. These statuettes are made by combining and assembling materials of contrasting colors. The preferred materials are chlorite (or similar dark green stones), a whitish limestone or mottled alabaster or marine shells from the Indian Ocean.[50] The different elements of body and costume were carved separately and joined, as in a puzzle, by tenon and mortices glue.

Axe with eagle-headed demon & animals; late 3rd millennium-early 2nd millennium BC; gilt silver; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Axe with eagle-headed demon & animals; late 3rd millennium-early 2nd millennium BC; gilt silver; length: 15 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Camel figurine; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; copper alloy; 8.89 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Camel figurine; late 3rd–early 2nd millennium BC; copper alloy; 8.89 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

.jpg.webp) Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; 2500–1500 BC; chlorite (dress and headdress) and limestone (head, hands and a leg); height: 13.33 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Female figurine of the "Bactrian princess" type; 2500–1500 BC; chlorite (dress and headdress) and limestone (head, hands and a leg); height: 13.33 cm; Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US)

Celtic

Celtic art is associated with the peoples known as Celts; those who spoke the Celtic languages in Europe from pre-history through to the modern period. It also refers to the art of ancient peoples whose language is uncertain, but have cultural and stylistic similarities with speakers of Celtic languages.

Celtic art is a difficult term to define, covering a huge expanse of time, geography and cultures. A case has been made for artistic continuity in Europe from the Bronze Age, and indeed the preceding Neolithic age; however archaeologists generally use "Celtic" to refer to the culture of the European Iron Age from around 1000 BC onwards, until the conquest by the Roman Empire of most of the territory concerned, and art historians typically begin to talk about "Celtic art" only from the La Tène period (broadly 5th to 1st centuries BC) onwards.[51] Early Celtic art is another term used for this period, stretching in Britain to about 150 AD.[52] The Early Medieval art of Britain and Ireland, which produced the Book of Kells and other masterpieces, and is what "Celtic art" evokes for much of the general public in the English-speaking world, is called Insular art in art history. This is the best-known part, but not the whole of, the Celtic art of the Early Middle Ages, which also includes the Pictish art of Scotland.[53]

The Amfreville helmet; by La Tène culture; late 4th century BC; bronze, iron, gold leaf and enamel; height: 21.4 cm; National Archaeological Museum of France (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France)

The Amfreville helmet; by La Tène culture; late 4th century BC; bronze, iron, gold leaf and enamel; height: 21.4 cm; National Archaeological Museum of France (Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France) Detail of the Battersea Shield; 4th to 3rd century BC; copper alloy and emanel; height: 77.5 cm; British Museum (London)

Detail of the Battersea Shield; 4th to 3rd century BC; copper alloy and emanel; height: 77.5 cm; British Museum (London) The Mšecké Žehrovice Head; 150-50 BC; marlstone; height: 23.4 cm, width: 17.4 cm; National Museum of the Czech Republic (Prague)

The Mšecké Žehrovice Head; 150-50 BC; marlstone; height: 23.4 cm, width: 17.4 cm; National Museum of the Czech Republic (Prague).jpg.webp) The Desborough mirror; 20 BC-20 AD; copper alloy; height (with handle): 35 cm; British Museum

The Desborough mirror; 20 BC-20 AD; copper alloy; height (with handle): 35 cm; British Museum

Achaemenid

Achaemenid art includes frieze reliefs, metalwork, decoration of palaces, glazed brick masonry, fine craftsmanship (masonry, carpentry, etc.), and gardening. Most survivals of court art are monumental sculpture, above all the reliefs, double animal-headed Persian column capitals and other sculptures of Persepolis.[54]

Although the Persians took artists, with their styles and techniques, from all corners of their empire, they produced not simply a combination of styles, but a synthesis of a new unique Persian style.[55][56] Cyrus the Great in fact had an extensive ancient Iranian heritage behind him; the rich Achaemenid gold work, which inscriptions suggest may have been a specialty of the Medes, was for instance in the tradition of earlier sites.

There are a number of very fine pieces of jewellery or inlay in precious metal, also mostly featuring animals, and the Oxus Treasure has a wide selection of types. Small pieces, typically in gold, were sewn to clothing by the elite, and a number of gold torcs have survived.[54]

Gold bracelet, part of the Oxus Treasure; 5th to 4th century BC; gold; width: 11.6 cm; British Museum (London)

Gold bracelet, part of the Oxus Treasure; 5th to 4th century BC; gold; width: 11.6 cm; British Museum (London).JPG.webp) Column capital; 5th to 4th century BC; stone; height: 1.75 m; from Persepolis; National Museum of Iran (Teheran)

Column capital; 5th to 4th century BC; stone; height: 1.75 m; from Persepolis; National Museum of Iran (Teheran)

Rome

Roman art is sometimes viewed as derived from Greek precedents, but also has its own distinguishing features. Roman sculpture is often less idealized than the Greek precedents, being very realistic. Roman architecture often used concrete, and features such as the round arch and dome were invented. Luxury objects in metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered in modern terms to be minor forms of Roman art,[57] although this would not necessarily have been the case for contemporaries.

Roman artwork was influenced by the nation-state's interaction with other people's, such as ancient Judea. A major monument is the Arch of Titus, which was erected by the Emperor Titus. Scenes of Romans looting the Jewish temple in Jerusalem are depicted in low-relief sculptures around the arch's perimeter.

Ancient Roman pottery was not a luxury product, but a vast production of "fine wares" in terra sigillata were decorated with reliefs that reflected the latest taste, and provided a large group in society with stylish objects at what was evidently an affordable price. Roman coins were an important means of propaganda, and have survived in enormous numbers.

Bronze statuette of a philosopher on a lamp stand; late 1st century BC; bronze; overall: 27.3 cm; weight: 2.9 kg; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Bronze statuette of a philosopher on a lamp stand; late 1st century BC; bronze; overall: 27.3 cm; weight: 2.9 kg; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

_from_the_Villa_of_P._Fannius_Synistor_at_Boscoreale_MET_DP170950.jpg.webp) Restoration of a fresco from an Ancient villa bedroom; 50-40 BC; dimensions of the room: 265.4 × 334 × 583.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Restoration of a fresco from an Ancient villa bedroom; 50-40 BC; dimensions of the room: 265.4 × 334 × 583.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Calyx-krater with reliefs of maidens and dancing maenads; 1st century AD; Pentelic marble; height: 80.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Calyx-krater with reliefs of maidens and dancing maenads; 1st century AD; Pentelic marble; height: 80.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Panoramic view of the Pantheon (Rome), built between 113 and 125

Panoramic view of the Pantheon (Rome), built between 113 and 125 Head of a goddess wearing a diadem; 1st–2nd century; marble; height: 23 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Head of a goddess wearing a diadem; 1st–2nd century; marble; height: 23 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Couch and footstool; 1st–2nd century AD; wood, bone and glass; couch: 105.4 × 76.2 × 214.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Couch and footstool; 1st–2nd century AD; wood, bone and glass; couch: 105.4 × 76.2 × 214.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Sarcophagus with Apollo, Minerva and the Muses; circa 200 AD; from Via Appia; Antikensammlung Berlin (Berlin)

Sarcophagus with Apollo, Minerva and the Muses; circa 200 AD; from Via Appia; Antikensammlung Berlin (Berlin)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Marine mosaic (central panel of three panels from a floor); 200–230; mosaic (stone and glass tesserae); height: 2,915 mm, width: 2,870 mm; Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, US)

Marine mosaic (central panel of three panels from a floor); 200–230; mosaic (stone and glass tesserae); height: 2,915 mm, width: 2,870 mm; Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, US) The Theseus Mosaic; 300–400; marble and limestone pebbles; 4.1 × 4.2 m; Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)

The Theseus Mosaic; 300–400; marble and limestone pebbles; 4.1 × 4.2 m; Kunsthistorisches Museum (Vienna, Austria)

Olmec

The olmecs were the earliest known major civilization in Mesoamerica following a progressive development in Soconusco. Olmec is the first to be elaborate as a pre-Columbian civilization of Mesoamerica (c. 1200–400 BC) and one that is thought to have set many of the fundamental patterns evinced by later American Indian cultures of Mexico and Central America, notably the Maya and the Aztec.

They lived in the tropical lowlands of south-central Mexico, in the present-day states of Veracruz and Tabasco. It has been speculated that the Olmecs derive in part from neighboring Mokaya or Mixe–Zoque. The Olmecs flourished during Mesoamerica's formative period, dating roughly from as early as 1500 BC to about 400 BC. Pre-Olmec cultures had flourished in the area since about 2500 BC, but by 1600–1500 BC, early Olmec culture had emerged, centered on the San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán site near the coast in southeast Veracruz.[58] They were the first Mesoamerican civilization, and laid many of the foundations for the civilizations that followed.

The Olmec culture was first defined as an art style, and this continues to be the hallmark of the culture.[59] Wrought in a large number of media – jade, clay, basalt, and greenstone among others – much Olmec art, such as The Wrestler, is naturalistic. Other art expresses fantastic anthropomorphic creatures, often highly stylized, using an iconography reflective of a religious meaning.[60] Common motifs include downturned mouths and a cleft head, both of which are seen in representations of were-jaguars.[59]

Colossal Head N° 1 of San Lorenzo, 1200 to 900 BCE, 2.9 metres (9 ft 6 in) high and 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) wide. A historical person, likely an Olmec leader, is depicted in this monumental sculpture found at San Lorenzo (in Tabasco, Mexico), a principal olmec center

Colossal Head N° 1 of San Lorenzo, 1200 to 900 BCE, 2.9 metres (9 ft 6 in) high and 2.1 metres (6 ft 11 in) wide. A historical person, likely an Olmec leader, is depicted in this monumental sculpture found at San Lorenzo (in Tabasco, Mexico), a principal olmec center Seated figurine; 12th–9th century BC; painted ceramic; height: 34 cm, width: 31.8 cm, depth: 14.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Seated figurine; 12th–9th century BC; painted ceramic; height: 34 cm, width: 31.8 cm, depth: 14.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Bird-shaped vessel; 12th–9th century BC; ceramic with red ochre; height: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Bird-shaped vessel; 12th–9th century BC; ceramic with red ochre; height: 16.5 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Kunz axe; 1200–400 BC; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

Kunz axe; 1200–400 BC; polished green quartz (aventurine); height: 29 cm, width: 13.5 cm; British Museum (London)

Middle Eastern

Pre-Islamic Arabia

The art of Pre-Islamic Arabia is related to that of neighbouring cultures. Pre-Islamic Yemen produced stylized alabaster heads of great aesthetic and historic charm. Most of the pre-Islamic sculptures are made of alabaster.

Archaeology has revealed some early settled civilizations in Saudi Arabia: the Dilmun civilization on the east of the Arabian Peninsula, Thamud north of the Hejaz, and Kindah kingdom and Al-Magar civilization in the central of Arabian Peninsula. The earliest known events in Arabian history are migrations from the peninsula into neighbouring areas.[61] In antiquity, the role of South Arabian societies such as Saba (Sheba) in the production and trade of aromatics not only brought such kingdoms wealth but also tied the Arabian peninsula into trade networks, resulting in far-ranging artistic influences.

It seems probable that before around 4000 BC the Arabian climate was somewhat wetter than today, benefitting from a monsoon system that has since moved south. During the late fourth millennium BC permanent settlements began to appear, and inhabitants adjusted to the emerging dryer conditions. In south-west Arabia (modern Yemen) a moister climate supported several kingdoms during the second and first millennia BC. The most famos of these is Sheba, the kingdom of the biblical Queen of Sheba. These societies used a combination of trade in spices and the natural resources of the region, including aromatics such as frankincense and myrrh, to build wealthy kingdoms. Mārib, the Sabaean capital, was well positioned to tap into Mediterranean as well as Near Eastern trade, and in kingdoms to the east, in what is today Oman, trading links with Mesopotamia, Persia and even India were possible. The area was never a part of the Assyrian or Persian empires, and even Babylonian control of north-west Arabia seems to have been relatively short-lived. Later Roman attempts to control the region's lucrative trade foundered. This impenetrability to foreign armies doubtless augmented ancient rulers' bargaining power in the spice and incense trade.

Although subject to external influences, south Arabia retained characteristics particular to itself. The human figure is typically based on strong, square shapes, the fine modeling of detail contrasting with a stylized simplicity of form.

Stele of a male wearing a baldric; 4th millennium BC; sandstone; height: 92 cm; from AlUla (Saudi Arabia); in a temporary exhibition in the National Museum of Korea (Seoul), named Roads of Arabia: Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia

Stele of a male wearing a baldric; 4th millennium BC; sandstone; height: 92 cm; from AlUla (Saudi Arabia); in a temporary exhibition in the National Museum of Korea (Seoul), named Roads of Arabia: Archaeological Treasures of Saudi Arabia Standing female figure wearing a strap and a necklace; 3rd–2nd millennium BC; sandstone and quartzite; height: 27.5 cm, width: 14.3 cm, depth: 14.3 cm; from Mareb (Yemen); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Standing female figure wearing a strap and a necklace; 3rd–2nd millennium BC; sandstone and quartzite; height: 27.5 cm, width: 14.3 cm, depth: 14.3 cm; from Mareb (Yemen); Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Incense burner; mid-1st millennium BC; bronze; height: 27.6 cm, width: 23.7 cm; depth: 23.3 cm; from Southwestern Arabia; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Incense burner; mid-1st millennium BC; bronze; height: 27.6 cm, width: 23.7 cm; depth: 23.3 cm; from Southwestern Arabia; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Funerary stele; 1st-3rd centuries AD; alabaster; height: 55 cm, width: 29 cm, depth: 8 cm; Louvre

Funerary stele; 1st-3rd centuries AD; alabaster; height: 55 cm, width: 29 cm, depth: 8 cm; Louvre Perfume-burner with an ibex; 1st–3rd century AD; limestone; from Yemen; height: 30 cm, width: 24 cm, depth: 24 cm; Louvre

Perfume-burner with an ibex; 1st–3rd century AD; limestone; from Yemen; height: 30 cm, width: 24 cm, depth: 24 cm; Louvre

Islamic

Some branches of Islam forbid depictions of people and other sentient beings, as they may be misused as idols. Religious ideas are thus often represented through geometric designs and calligraphy. However, there are many Islamic paintings which display religious themes and scenes of stories common among the three Abrahamic monotheistic faiths of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism.

The influence of Chinese ceramics has to be viewed in the broader context of the considerable importance of Chinese culture on Islamic arts in general.[62] The İznik pottery (named after İznik, a city from Turkey) is one of the best well-known types of Islamic pottery. Its famous combination between blue and white is a result of that Ottoman court in Istanbul who greatly valued Chinese blue-and-white porcelain.

.jpg.webp) Manuscript page; 950–1000; paper, ink, gold, watercolours and leather; height: 55 cm, width: 38 cm; Al-Sabah Collection (Kuwait)

Manuscript page; 950–1000; paper, ink, gold, watercolours and leather; height: 55 cm, width: 38 cm; Al-Sabah Collection (Kuwait)

Brazier; second half of the 13th century; brass, cast, chased, inlaid with silver and black compound; height: 35.2 cm, width: 39.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Brazier; second half of the 13th century; brass, cast, chased, inlaid with silver and black compound; height: 35.2 cm, width: 39.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Mosque lamp; shortly after 1285; enameled and gilded glass; height: 26.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mosque lamp; shortly after 1285; enameled and gilded glass; height: 26.4 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art_MET_DP235035.jpg.webp)

Persian miniature of the Mi'raj of the Prophet by Sultan Mohammed, showing Chinese-influenced clouds and angels; 1539–1543; gouache and ink on paper; height: 28.7 cm; British Library (London)

Persian miniature of the Mi'raj of the Prophet by Sultan Mohammed, showing Chinese-influenced clouds and angels; 1539–1543; gouache and ink on paper; height: 28.7 cm; British Library (London) İznik dish; 16th century; stonepaste, polychrome-painted under transparent glaze; height: 6 cm, diameter: 27.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

İznik dish; 16th century; stonepaste, polychrome-painted under transparent glaze; height: 6 cm, diameter: 27.9 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Carpet; 17th century; cotton (warp and weft) and wool (pile), asymmetrically knotted pile; length: 247.65 cm, width: 142.87 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Carpet; 17th century; cotton (warp and weft) and wool (pile), asymmetrically knotted pile; length: 247.65 cm, width: 142.87 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Siberian-Eskimo

The art of the Eskimo people from Siberia is in the same style as the Inuit art from Alaska and north Canada. This is because the Native Americans traveled through Siberia to Alaska, and later to the rest of the Americas.

In the Russian Far East, the population of Siberia numbers just above 40 million people. As a result of the 17th-to-19th-century Russian conquest of Siberia and the subsequent population movements during the Soviet era, the demographics of Siberia today is dominated by native speakers of Russian. There remain a considerable number of indigenous groups, between them accounting for below 10% of total Siberian population, which are also genetically related to Indigenous Peoples of the Americas.

Americas

The history of art in the Americas begins in pre-Columbian times with Indigenous cultures. Art historians have focused particularly closely on Mesoamerica during this early era, because a series of stratified cultures arose there that erected grand architecture and produced objects of fine workmanship that are comparable to the arts of Western Europe.

Preclassic

The art-making tradition of Mesoamerican people begins with the Olmec around 1400 BC, during the Preclassic era. These people are best known for making colossal heads but also carved jade, erected monumental architecture, made small-scale sculpture, and designed mosaic floors. Two of the most well-studied sites artistically are San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán and La Venta. After the Olmec culture declined, the Maya civilization became prominent in the region. Sometimes a transitional Epi-Olmec period is described, which is a hybrid of Olmec and Maya. A particularly well-studied Epi-Olmec site is La Mojarra, which includes hieroglyphic carvings that have been partially deciphered.

Classic

By the late pre-Classic era, beginning around 400 BC, the Olmec culture had declined but both Central Mexican and Maya peoples were thriving. Throughout much of the Classic period in Central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan was thriving, as were Xochicalco and El Tajin. These sites boasted grand sculpture and architecture. Other Central Mexican peoples included the Mixtecs, the Zapotecs, and people in the Valley of Oaxaca. Maya art was at its height during the "Classic" period—a name that mirrors that of Classical European antiquity—and which began around 200 CE. Major Maya sites from this era include Copan, where numerous stelae were carved, and Quirigua where the largest stelae of Mesoamerica are located along with zoomorphic altars. A complex writing system was developed, and Maya illuminated manuscripts were produced in large numbers on paper made from tree bark. Many sites "collapsed" around 1000 CE.

Postclassic

At the time of the Spanish conquest of Yucatán during the 16th and 17th centuries, the Maya were still powerful, but many communities were paying tribute to Aztec society. The latter culture was thriving, and it included arts such as sculpture, painting, and feather mosaics. Perhaps the most well-known work of Aztec art is the calendar stone, which became a national symbol of the state of Mexico. During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, many of these artistic objects were sent to Europe, where they were placed in cabinets of curiosities, and later redistributed to Western art museums. The Aztec empire was based in the city of Tenochtitlan which was largely destroyed during the colonial era. What remains of it was buried beneath Mexico City. A few buildings, such as the foundation of the Templo Mayor have since been unearthed by archaeologists, but they are in poor condition.

Art in the Americas

Art in the Americas since the conquest is characterized by a mixture of indigenous and foreign traditions, including those of European, African, and Asian settlers. Numerous indigenous traditions thrived after the conquest. For example, the Plains Indians created quillwork, beadwork, winter counts, ledger art, and tipis in the pre-reservation era, and afterwards became assimilated into the world of Modern and Contemporary art through institutions such as the Santa Fe Indian School which encouraged students to develop a unique Native American style. Many paintings from that school, now called the Studio Style, were exhibited at the Philbrook Museum of Art during its Indian annual held from 1946 to 1979.

Aztec

_MET_DT5110.jpg.webp)

Arising from the humblest beginnings as a nomadic group of "uncivilizated" wanderers, the Aztecs created the largest empire in Mesoamerican history, lasting from 1427/1428 to 1521. Tribute from conquered states provided the economic and artistic resources to transform their capital Tenochtitlan (0ld Mexico City) into one of the wonders of the world. Artists from throughout mesoamerica created stunning artworks for their new masters, fashioning delicate golden objects of personal adornment and formidable sculptures of fierce gods.

The Aztecs entered the Valley of Mexico (the area of modern Mexico City) in 1325 and within a century had taken control of this lush region brimming with powerful city-states. Their power was based on unbending faith in the vision of their patron deity Huitzilopochtli, a god of war, and in their own unparalleled military prowess.

The grandiosity of the Aztec state was reflected in the comportment of the nobility and warriors who had distinguished themselves in battle. Their finely woven and richly embellished clothing was accentuated by iridescent tropical bird feathers and ornate jewellery made of gold, silver, semi-precious stones and rare shells.

Aztec art may be direct and dramatic or subtle and delicate, depending on the function of the work. The finest pieces, from monumental sculptures to masks and gold jewellery, display outstanding craftsmanship and aesthetic refinement. This same sophistication characterizes Aztec poetry, which was renowned for its lyrical beauty and spiritual depth. Aztec feasts were not complete without a competitive exchange of verbal artistry among the finely dressed noble guests.

.jpg.webp) The Mask of Xiuhtecuhtli; 1400–1521; cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, mother-of-pearl, conch shell, cinnabar; height: 16.8 cm, width: 15.2 cm; British Museum (London)

The Mask of Xiuhtecuhtli; 1400–1521; cedrela wood, turquoise, pine resin, mother-of-pearl, conch shell, cinnabar; height: 16.8 cm, width: 15.2 cm; British Museum (London) The Mask of Tezcatlipoca; 1400–1521; turquoise, pyrite, pine, lignite, human bone, deer skin, conch shell and agave; height: 19 cm, width: 13.9 cm, length: 12.2 cm; British Museum

The Mask of Tezcatlipoca; 1400–1521; turquoise, pyrite, pine, lignite, human bone, deer skin, conch shell and agave; height: 19 cm, width: 13.9 cm, length: 12.2 cm; British Museum Double-headed serpent; 1450–1521; cedro wood (Cedrela odorata), turquoise, shell, traces of gilding & 2 resins are used as adhesive (pine resin and Bursera resin); height: 20.3 cm, width: 43.3 cm, depth: 5.9 cm; British Museum

Double-headed serpent; 1450–1521; cedro wood (Cedrela odorata), turquoise, shell, traces of gilding & 2 resins are used as adhesive (pine resin and Bursera resin); height: 20.3 cm, width: 43.3 cm, depth: 5.9 cm; British Museum.jpg.webp) Page 12 of the Codex Borbonicus, (in the big square): Tezcatlipoca (night and fate) and Quetzalcoatl (feathered serpent); before 1500; bast fiber paper; height: 38 cm, length of the full manuscript: 142 cm; Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale (Paris)

Page 12 of the Codex Borbonicus, (in the big square): Tezcatlipoca (night and fate) and Quetzalcoatl (feathered serpent); before 1500; bast fiber paper; height: 38 cm, length of the full manuscript: 142 cm; Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale (Paris) Aztec calendar stone; 1502–1521; basalt; diameter: 358 cm; thick: 98 cm; discovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral; National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City)

Aztec calendar stone; 1502–1521; basalt; diameter: 358 cm; thick: 98 cm; discovered on 17 December 1790 during repairs on the Mexico City Cathedral; National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City) Tlāloc effigy vessel; 1440–1469; painted earthenware; height: 35 cm; Museo del Templo Mayor (Mexico City)

Tlāloc effigy vessel; 1440–1469; painted earthenware; height: 35 cm; Museo del Templo Mayor (Mexico City) Kneeling female figure; 15th–early 16th century; painted stone; overall: 54.61 × 26.67 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Kneeling female figure; 15th–early 16th century; painted stone; overall: 54.61 × 26.67 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Frog-shaped necklace ornaments; 15th–early 16th century; gold; height: 2.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Frog-shaped necklace ornaments; 15th–early 16th century; gold; height: 2.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Mayan

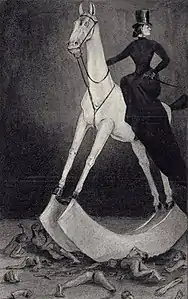

Ancient Maya art refers to the material arts of the Maya civilization, an eastern and south-eastern Mesoamerican culture that took shape in the course of the later Preclassic Period (500 BC to 200 AD). Its greatest artistic flowering occurred during the seven centuries of the Classic Period (c. 200 to 900 CE). Ancient Maya art then went through an extended Post-Classic phase before the upheavals of the sixteenth century destroyed courtly culture and put an end to the Mayan artistic tradition. Many regional styles existed, not always coinciding with the changing boundaries of Maya polities. Olmecs, Teotihuacan and Toltecs have all influenced Maya art. Traditional art forms have mainly survived in weaving and the design of peasant houses.