Liberation of France

The Liberation of France is the ensemble of diplomatic, political, internal resistance, and military engagements during the Second World War in which German-occupied France was progressively liberated by the combined efforts of Free French forces based in London and North Africa, the Allied military forces, and the actions of the French Resistance inside the country. Resistance to the occupation began with General Charles de Gaulle, who fled to London to organize Free France to fight against capitulation to Germany, to urge resistance efforts within France, and to persuade France's colonial territories in northern Africa to abandon Vichy and support the Free French, which they did in 1943. The turning point was in 1944, when Allied forces invaded France from the north and the south in two major military operations, driving German forces out of France and liberating most of the country by September 1944, with some clean-up operations continuing, especially along the Atlantic coast until the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945.

| Liberation of France | |||

|---|---|---|---|

De Gaulle speaking from Cherbourg City Hall balcony 20 August 1944 | |||

| |||

France was invaded by Nazi Germany in May 1940 and fell in six weeks, signing an armistice in June. In July, the French Third Republic dissolved itself, and in the last act of the National Assembly handed over dictatorial powers to Marshal Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I, who became prime minister. Pétain established an authoritarian government at Vichy in the southern, so-called "Free zone". Nominally independent, Vichy France became a collaborationist regime and was little more than a Nazi client state. The occupied zone in the northern and western part of the country was placed under German military occupation.

Resistance began even before the armistice was signed. French General Charles de Gaulle fled to London and formed a government-in-exile as Free France with the backing of Winston Churchill for recognition and funding. De Gaulle broadcast his radio Appeal of 18 June to his fellow citizens, calling for resistance against the Germans. While World War II raged in western Europe, inside France, small, independent cells of fighters began to organize local resistance in guerilla actions, interfering with German communications and disrupting rail transport.

Efforts to liberate France began in France's colonial empire in Northern Africa. In the fall of 1940, the colonial empire largely supported the Vichy regime, but after governor Félix Éboué of French Chad switched his support to General de Gaulle, the general traveled to Brazzaville and announced formation of the Empire Defense Council and invited all colonies still supporting Vichy to join him in the fight against Germany, which most of them did by 1943.

Militarily, the liberation of France was part of the Western Front of World War II. Other than scattered raids in 1942 and 1943, the reconquest began in earnest in the summer of 1944 in campaigns in the north and south of France. On 6 June 1944, the Allies began Operation Overlord (D-Day) in the largest seaborne invasion in history, establishing a beachhead in Normandy, landing two million men in northern France and opening another front in western Europe against Germany. In the south, the Allies launched Operation Dragoon on 15 August, opening a front on the Mediterranean. In four weeks, the Germans withdrew from southern France, retreating to Germany, and leaving French ports in Allied hands, resolving earlier supply problems in the south. With the Allied onslaught from both directions, the French Resistance organized a general uprising in Paris on 19 August, and on 25 August 1944 Paris was liberated. The Allied forces began to push towards Germany. Initial rapid advances in the north stretched lines of supply in the autumn, and the advance slowed. German counteroffensives in the winter of 1944-45 such as the Battle of the Bulge slowed but did not stop the Allied armies, some crossing the Rhine into Germany in February, with heavy German losses. By late March several Allied armies had crossed and began advancing rapidly into Germany, with the end of the war not far away. With France mostly liberated, a few pockets of German resistance remained until the end of the war on 8 May 1945.

During the struggle for Paris, Pétain and the remains of the Vichy regime left France for Sigmaringen, Germany, where the puppet government-in-exile and their entourage survived until April 1945. Some escaped; Pétain was arrested by French forces, tried, and sentenced; Pierre Laval was executed. Immediately following liberation, France was swept by a wave of executions, assaults, and degradation of suspected collaborators, including shaming of women suspected of "horizontal collaboration". Courts set up in June 1944 carried out an official purge of officials tainted by their association with Vichy or the occupiers, including death sentences. The first elections since 1940 were organized in May 1945 by the Provisional Government and carried out in two rounds just before and after the unconditional surrender on 8 May 1945, and were also the first in which women could vote. In referendums in October 1946, the voters approved a new Constitution and the Fourth Republic was born 27 October 1946.

Background

Fall of France and rise of Vichy

France was invaded by Nazi Germany beginning on 10 May 1940. The Nazis rapidly conquered France by bypassing the highly fortified Maginot Line and invading through Belgium. By July, the military situation of the French was dire, and it was apparent that the French had lost. The French government began to discuss the possibility of an armistice. Paul Reynaud resigned as prime minister of the Third French Republic rather than sign an armistice, and Marshal Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I, became prime minister. Shortly thereafter, Pétain signed the Armistice of 22 June. On 10 July, the Third Republic was effectively dissolved as Pétain was granted essentially dictatorial powers by the National Assembly.

At Vichy, Pétain established an authoritarian government that reversed many liberal policies and began tight supervision of the economy. Conservative Catholics became prominent and Paris lost its avant-garde status in European art and culture. The media were tightly controlled and promoted anti-Semitism, and, after June 1941, anti-Bolshevism.[1] The occupation presented certain advantages, such as keeping the French Navy and French colonial empire under French control, and avoiding full occupation of the country by Germany, thus maintaining a degree of French independence and neutrality. Despite heavy pressure, the French government at Vichy never joined the Axis alliance and even remained formally at war with Germany. Conversely, Vichy France became a collaborationist regime, and was little more than a Nazi client state.

French military tacticians had failed to predict the German invasion route through the Ardennes, considered impassable by tanks. French defenses swiftly crumbled as the Germans swept through the Lowlands and around the heavily fortified Maginot Line. The only question in French politics was whether to seek an armistice, fight on, or simply surrender. Paul Reynaud wanted to fight on from North Africa but had no support and resigned rather than seek an armistice.[2]

The Assemblée Nationale voted to give World War hero Philippe Pétain the power to write a new constitution, which he interpreted as a writ of absolute power, dissolving the constitution of the French Third Republic that had been in existence since the fall of the monarchy. In hopes of preventing its destruction, Reynaud declared Paris an open city. The Pétain administration fled, but not to North Africa as Reynaud had wanted, establishing itself instead at Vichy in the southern zone.[3] The Germans advanced to Paris, and down the Atlantic coast. The Vichy régime nominally governed all of France, but in practice the Zone occupée was a Nazi dictatorship, and Vichy's power even in the zone libre was limited and uncertain.

State collaboration was sealed by the Montoire interview in Hitler's train on 24 October 1940, during which Pétain and Hitler shook hands and agreed on co-operation between the two states. Organized by Pierre Laval, a strong proponent of collaboration, the interview and the handshake were photographed and exploited by Nazi propaganda to gain the support of the civilian population. On 30 October 1940, Pétain made state collaboration official, declaring on the radio: "I enter today on the path of collaboration."[lower-alpha 1] On 22 June 1942, Laval declared that he was "hoping for the victory of Germany".[4]

De Gaulle launches Free France

Refusing to accept his government's armistice with Germany, Charles de Gaulle fled to England on 17 June and exhorted the French to resist occupation and to continue the fight in his Appeal of 18 June on BBC radio.

De Gaulle also tried, largely in vain, to attract the support of French forces in the French Empire. His overtures to General Charles Noguès (Resident-General in Morocco and Commander-in-Chief of French forces in North Africa) were refused, and Noguès forbade the press in French North Africa to publish de Gaulle's appeal.[5] After the armistice was signed on 21 June 1940, de Gaulle spoke at 20:00 on 22 June to denounce it.[6] The French government, which now convened in Bordeaux, declared de Gaulle compulsorily retired from the Army with the rank of colonel on 23 June 1940.[7] On 23 June the British Government denounced the armistice and stated that they no longer regarded the Bordeaux Government as a fully independent state. They also noted the plan to establish a French National Committee in exile, but without mentioning de Gaulle by name.[8]

The armistice took effect from 00:35 on 25 June.[6] On 26 June de Gaulle wrote to Churchill demanding recognition of his French Committee.[9] On 28 June, after Churchill's envoys had failed to establish contact with the French leaders in North Africa, the British Government recognized de Gaulle as leader of the Free French, despite the reservations of the foreign office.[10]

De Gaulle had little success in attracting the support of major figures.[11] While Philippe Pétain's government was recognized by the US, the USSR, and the Papacy, and controlled the French fleet and the forces in almost all the colonies, de Gaulle's retinue consisted of a secretary, three colonels, a dozen captains, a law professor, and three battalions of legionnaires who had agreed to stay in Britain and fight for him. For a time the New Hebrides were the only French colony to back de Gaulle.[12]

The Vichy regime sentenced de Gaulle to death by court martial in absentia.[7] De Gaulle said of the sentence, "I consider the act of the Vichy men as void; I shall have an explanation with them after the victory".[13] De Gaulle and Churchill reached agreement on 7 August 1940, that Britain would fund the Free French, with the bill to be settled after the war (the financial agreement was finalized in March 1941). A separate letter guaranteed the territorial integrity of the French Empire.[14]

French Resistance

The French Resistance was a decentralized organization of small cells of fighters with the tacit or overt support of many French civilians. Some were former Republican fighters from the Spanish Civil War; others were workers who went into hiding rather than report for the mandatory Service du travail obligatoire in Germany.[15] In the south of France especially, Resistance fighters took to the mountainous maquis and conducted guerilla warfare on the German occupation forces, cutting telephone lines and destroying bridges.

Some organizations grew up around one of the many clandestine presses of the time. Stalin supported the effort once the Nazis invaded Russia. French prisoners of war were held hostage against the French government providing a sufficient workforce for German factories, but when the Vichy government began wholesale impressment of able-bodied civilians to meet German demands, railway workers (cheminots) went on strike.[16] They eventually formed their own organization, Résistance-Fer. The Unione Corse and the milieu, the criminal underground of Marseilles, gleefully provided logistical assistance for a price, although some such as Paul Carbone worked with the Carlingue instead.

The French Forces of the Interior, as de Gaulle came to call Resistance forces, were an uneasy alliance of multiple maquis and other organizations , including the Communist-organized Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (FTP) and the Armée secrète in southern France. In addition, escape networks helped Allied airmen who had been shot down get to safety.

The Germans had begun to demand French workers for German arms factories. Dissatisfied with the number of volunteers, the German military administration in occupied France during World War II had the Government of Vichy France enact the mandatory Service du travail obligatoire, and able-bodied French citizens began to disappear into forests and mountain wildernesses to join the maquis.[17]

French colonial empire

France's colonial empire at the start of World War II stretched from territories and possessions in Africa, the Middle East (Syria and Lebanon), ports in India, Indochina, Pacific islands, and even territories in North and South America. By 1943, all of the colonies, except for Indochina under Japanese control, had joined the Free French cause.[18][19]

The colonies in Africa, in particular, would play a key role in the liberation of France.

Diplomacy, politics, and administration

Political and diplomatic efforts to liberate France started with Charles de Gaulle in London and his radio appeal of 18 June and spanned the war, culminating with his installation in 1946 at the head of the Provisional Government after liberation. In between, there were many diplomatic and political efforts involved in the liberation of France, mostly centering around the figure of de Gaulle and involving various organizations, including the Empire Defense Council, the French National Committee, the French Committee of National Liberation, and the Provisional Government of the French Republic.

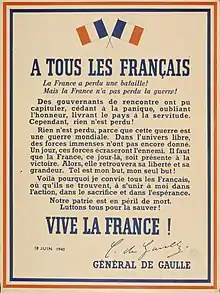

Appeal of 18 June

Refusing to accept his government's armistice with Germany, Charles de Gaulle fled to England on 17 June and exhorted the French to resist occupation and to continue the fight in his Appeal of 18 June on BBC radio. This marked a key first step in opposition to the German occupation, which ultimately led to the liberation of France.[20]

Before fleeing France, de Gaulle had recently been promoted to the rank of Brigadier General and named as Under-Secretary of State for National Defence and War by Prime Minister Paul Reynaud during the German invasion of France.[22][23] Reynaud resigned after his proposal for a Franco-British Union was rejected by his cabinet and Marshal Philippe Pétain, a hero of World War I, became the new Prime Minister, pledging to sign an armistice with Nazi Germany. De Gaulle opposed any such action and facing imminent arrest, fled France on 17 June. Other leading politicians, including Georges Mandel, Léon Blum, Pierre Mendès France, Jean Zay and Édouard Daladier (and separately Reynaud), were arrested while travelling to continue the war from North Africa.[24]:211–216

De Gaulle obtained special permission from Winston Churchill to broadcast a speech on 18 June via BBC Radio from Broadcasting House over France, despite the British Cabinet's objections that such a broadcast could provoke the Pétain government into a closer allegiance with Germany.[25] In his speech, de Gaulle reminded the French people that the British Empire and the United States of America would support them militarily and economically in an effort to retake France from the Germans.

The BBC did not record the speech,[lower-alpha 3][27] and few actually heard it. Another speech, which was recorded and heard by more people, was given by de Gaulle four days later. There is a record, however, of the manuscript of the speech of 18 June,[27] which has been found in the archives of the Swiss intelligence agencies who published the text for their own uses on 19 June. The manuscript of the speech, as well as the recording of the 22 June speech, were nominated on 18 June 2005 for inclusion in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register by the BBC, which called it "one of the most remarkable pieces in the history of radio broadcasting."[28]

After the war, de Gaulle's radio appeal was often identified as the beginning of the French Resistance, and the process of liberating France from the yoke of German occupation.[29]

Northern Africa

De Gaulle's support grew out of a base in colonial Africa. In the fall of 1940, the colonial empire largely supported the Vichy regime. Félix Éboué, governor of Chad, switched his support to General de Gaulle in September. Encouraged, de Gaulle traveled to Brazzaville in October, where he announced the formation of an Empire Defense Council[30] in his "Brazzaville Manifesto",[31] and invited all colonies still supporting Vichy to join him and the Free French forces in the fight against Germany, which most of them did by 1943.[30][32]

On 26 August, the governor and military commanders in the colony of French Chad announced that they were rallying to De Gaulle's Free French Forces. A small group of Gaullists seized control of French Cameroon the following morning, and on 28 August a Free French official ousted the pro-Vichy governor of French Congo. The next day the governor of Ubangi-Shari declared that his territory would support De Gaulle. His declaration prompted a brief struggle for power with a pro-Vichy army officer, but by the end of the day all of the colonies that formed French Equatorial Africa had rallied to Free France, except for French Gabon.[33]

Administration

A series of organizing bodies was created during the war, to guide and coordinate the diplomatic and war effort of Free France. A week after his 18 June radio appeal from London, Charles de Gaulle established the Empire Defense Council, which served till 1941. Churchill prodded de Gaulle to set up something more formal, and in September 1941 de Gaulle created the French National Committee. This lasted until June 1943, when it when it merged with the civilian and military command in North Africa under Henri Giraud, forming the new French Committee of National Liberation which de Gaulle took over in September 1943. In August 1944, after the liberation of Paris, the Committee moved to Paris and was reorganized as the Provisional Government of the French Republic under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle. The Provisional Government guided the war and diplomatic efforts through liberation and the end of the war, until the writing of a new Constitution and establishment of the Fourth Republic in October 1946.

Empire Defense Council

The Empire Defense Council was the embodiment of Free France which constituted the government from 1940 to 1941.

On 26 June 1940, four days after the Pétain government requested the armistice, General de Gaulle submitted a memorandum to the British government notifying Churchill of his decision to set up a Council of Defense of the Empire[34] and formalizing the agreement reached with Churchill on 28 June.

The formal recognition of the Empire Defense Council as a government in exile by the United Kingdom took place on 6 January 1941; recognition by the Soviet Union was published in December 1941, by exchange of letters.[35]

French National Committee

The French National Committee was created by General Charles de Gaulle as the successor organization to the smaller Empire Defense Council. It was the coordinating body which acted as the government-in-exile of Free France from 1941 to 1943. [36]

It was Winston Churchill who suggested that de Gaulle create a committee, in order to lend an appearance of a more constitutionally based and less dictatorial authority.[37] According to historian Henri Bernard, De Gaulle went on to accept his proposal, but took care to exclude all his adversaries within the Free France movement, such as Émile Muselier, André Labarthe and others, retaining only "yes men" in the group.[37]

The Committee was founded 24 September 1941 by an edict signed by General de Gaulle in London. The committee remained active until 3 June 1943, when it merged with the civilian and military forces in North Africa headed by Henri Giraud, becoming the new French Committee of National Liberation.

French Committee of National Liberation

The French Committee of National Liberation was a provisional government of Free France formed by generals Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle to provide united leadership, organize and coordinate the campaign to liberate France. The committee was formed on 3 June 1943 and after a period of joint leadership came under the chairmanship of de Gaulle on 9 November it .[38] The committee directly challenged the legitimacy of the Vichy regime and unified all the French forces that fought against the Nazis and collaborators. The committee functioned as a provisional government for Algeria (then a part of metropolitan France) and the liberated parts of the colonial empire. [39][40][41]

The Committee was formed on 3 June 1943 in Algiers, the capital of French Algeria [41] Giraud and de Gaulle served jointly as co-presidents of the committee. The charter of the body affirmed its commitment to "re-establish all French liberties, the laws of the Republic and the Republican regime."[42] The committee saw itself as a source of unity and representation for the French nation. The Vichy regime was decried as illegitimate over its collaboration with Nazi Germany. The Committee received mixed responses from the Allies; the U.S. and Britain considered it a war-time body with restricted functions, being different from a future government of liberated France.[42] The Committee soon expanded its membership, developed a distinctive administrative body and incorporated as the Provisional Consultative Assembly, creating an organized, representative government within itself. With Allied recognition, the Committee and its leaders, Gens. Giraud and de Gaulle enjoyed considerable popular support within France and the French resistance, thus becoming the forerunners in the process to form a provisional government for France as liberation approached.[42] However, Charles de Gaulle politically outmaneuvered Gen. Giraud, and asserted complete control and leadership over the Committee.[41]

in August 1944 the Committee moved to Paris, following the liberation of France by Allied forces.[42]

In September, Allied forces recognized the Committee as the legitimate, provisional government of France, whereupon the Committee reorganized itself as the Provisional Government of the French Republic under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle[42] and began the process of writing a new Constitution which would become the basis of the French Fourth Republic.[41]

Provisional Consultative Assembly

The Provisional Consultative Assembly was a governmental organ of Free France that was created by and operated under the aegis of the French Committee of National Liberation (CFLN). It began in north Africa and held meetings in Algiers until it moved to Paris in July 1944. Led by Charles de Gaulle, it was an attempt to provide some sort of representative, democratic accountability to the institutions being set up to represent the French people, at a time when the country itself and its laws were dissolved and its territory occupied or coopted with a puppet state.

The members of the Assembly represented the French resistance movements, political parties, and territories that were engaged against Germany in the Second World War alongside the Allies.

Established by ordinance on 17 September 1943 by the CFLN, it held its first meetings in Algiers, at the Palais Carnot (the former headquarters of the Financial Delegations), between 3 November 1943 and 25 July 1944. On 3 June 1944 it was placed under the authority of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), which succeeded the CFLN.

In his inaugural speech, de Gaulle gave the body his imprimatur, as providing a means of representing the people of France as democratically and legally as possible under difficult and unparalleled circumstances, until such time as democracy could once again be restored.[43][44] As an indication of the importance he attached to the body, de Gaulle participated in about twenty sessions of the Consultative Assembly in Algiers. On 26 June 1944, he came to report on the military situation after the D-Day landings, and on 25 July, he was present at its last session on African soil before its move to Paris.[44]

Restructured and expanded after the liberation of France, it held sessions in Paris at the Palais du Luxembourg between 7 November 1944 and 3 August 1945.

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPFR) was the successor organization to the French Committee of National Liberation. It served as an interim government of Free France from June 1944, through liberation and lasted till 1946.

The PGFR was created by the Committee of National Liberation on 3 June 1944, three days before D-day. It moved back to Paris after the liberation of the capital in August 1944.

Most of the goals and activity of the GPFR are related to the post-Liberation period, so this subtopic is covered in more detail in the Aftermath section below, in section Provisional Government of the French Republic.

Military forces

The first military forces brought to bear in the liberation of France were the forces of Free France, made up of soldiers from France's colonial empire in Africa. The major players militarily were two of the Big Three Allies, namely the United States and the United Kingdom, assisted by the other Allies of World War II, such as the Canadians and Australians who participated in the invasion of France in Operation Overlord.

Inside France, the numerous and scattered cells of the French Resistance were gradually consolidated into a fighting force after the Normany landings and became known as the French Forces of the Interior. The FFI made major contributions assisting Allied armies pushing the Germans out of France and in the eastward advance towards the Rhine.

Free French Forces

Despite de Gaulle's call to continue the struggle, few French forces initially pledged their support. By the end of July 1940, only about 7,000 soldiers had joined the Free French Army in England.[45][46] Three-quarters of French servicemen in Britain requested repatriation.[47]

France was bitterly divided by the conflict. Frenchmen everywhere were forced to choose sides, and often deeply resented those who had made a different choice.[48] One French admiral, René-Émile Godfroy, voiced the opinion of many of those who decided not to join the Free French forces, when in June 1940, he explained to the exasperated British why he would not order his ships from their Alexandria harbour to join de Gaulle:

- "For us Frenchmen, the fact is that a government still exists in France, a government supported by a Parliament established in non-occupied territory and which in consequence cannot be considered irregular or deposed. The establishment elsewhere of another government, and all support for this other government would clearly be rebellion."[48]

Equally, few Frenchmen believed that Britain could stand alone. In June 1940, Pétain and his generals told Churchill that "in three weeks, England will have her neck wrung like a chicken".[49] Of France's far-flung empire, only the French domains of St Helena (on 23 June at the initiative of Georges Colin, honorary consul of the domains[50]) and the Franco-British ruled New Hebrides condominium in the Pacific (on 20 July) answered De Gaulle's call to arms. It was not until late August that Free France would gain significant support in French Equatorial Africa.[51]

Unlike the troops at Dunkirk or naval forces at sea, relatively few members of the French Air Force had the means or opportunity to escape. Like all military personnel trapped on the mainland, they were functionally subject to the Pétain government: "French authorities made it clear that those who acted on their own initiative would be classed as deserters, and guards were placed to thwart efforts to get on board ships."[52] In the summer of 1940, around a dozen pilots made it to England and volunteered for the RAF to help fight the Luftwaffe.[53][54] Many more, however, made their way through long and circuitous routes to French territories overseas, eventually regrouping as the Free French Air Force.[55]

The French Navy was better able to immediately respond to de Gaulle's call to arms. Most units initially stayed loyal to Vichy, but about 3,600 sailors operating 50 ships around the world joined with the Royal Navy and formed the nucleus of the Free French Naval Forces (FFNF; in French: FNFL).[46] France's surrender found her only aircraft carrier, Béarn, en route from the United States loaded with a precious cargo of American fighter and bomber aircraft. Unwilling to return to occupied France, but likewise reluctant to join de Gaulle, Béarn instead sought harbour in Martinique, her crew showing little inclination to side with the British in their continued fight against the Nazis. Already obsolete at the start of the war, she would remain in Martinique for the next four years, her aircraft rusting in the tropical climate.[56]

Many of the men in the French colonies felt a special need to defend France, their distant "motherland", eventually making up two-thirds of de Gaulle’s Free French Forces. Among these volunteers, influential psychiatrist and decolonial philosopher Frantz Fanon, from Martinique, joined de Gaulle’s troops at the age of 18, despite being deemed a ‘dissenter’ by Martinique’s Vichy-controlled colonial government for doing so.[57]

Colonial African forces

The contribution to France's liberation made by French colonial African soldiers, who comprised 9% of the French army, has largely been ignored. The Gaullists made their base in African territory to launch the military liberation. Among the populations colonized by France, it was African troops who made the largest contribution to the liberation campaign. [58][59]

The Armée d’Afrique was formally a separate army corps of the French metropolitan army, the. 19th Army Corps (19e Corps d'Armée) so named in 1873. The French Colonial Forces on the other hand came under the Ministry of the Navy and comprised both French and indigenous units serving in Sub-Saharan Africa and elsewhere in the French colonial empire.

Intelligence

De Gaulle set up his Free French intelligence system to combine both military and political roles, including covert operations. He selected journalist Pierre Brossolette (1903-44) to head the Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action (BCRA). The policy was reversed in 1943 by Emmanuel d'Astrier the interior minister of the exile government, who insisted on civilian control of political intelligence.[60]

Allied forces

The "Big Three" of the Allies of World War II that defeated Germany in the war were the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Soviet Union fought Germany on the Eastern Front and so played no direct role in the liberation of France, but were instrumental in the ultimate defeat of Nazi Germany.

The United Kingdom and the United States were the main Allies on the Western Front whose military actions led to the liberation of France. Other Allies made major contributions, such as the 14,000 Canadian soldiers who landed in Normandy on D-Day, or the Australians who supported the invasion from the air, and contributed 3,000 soldiers to the landings.

French Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior were French resistance fighters in the later stages of the war. General de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation of these groups to FFI occurred as France's status changed from that of an occupied nation to one of a nation being liberated by the Allied armies. As regions of France were liberated, the FFI were more formally organized into light infantry units and served as a valuable manpower addition to regular Free French forces.

After the invasion of Normandy in June 1944, at the request of the French Committee of National Liberation, SHAEF placed about 200,000 resistance fighters under command of General Marie Pierre Kœnig,[61] who attempted to unify resistance efforts against the Germans. General Eisenhower confirmed Koenig's command of the FFI on 23 June 1944.

The FFI were mostly composed of resistance fighters who used their own weapons, although many FFI units included former French soldiers. They used civilian clothing and wore an armband with the letters "F.F.I."

According to General Patton, the rapid advance of his army through France would have been impossible without the fighting aid of the FFI. General Patch estimated that from the time of the Mediterranean landings to the arrival of U.S. troops at Dijon, the help given to the operations by the FFI was equivalent to four full divisions.[62]

FFI units seized bridges, began the liberation of villages and towns as Allied units neared, and collected intelligence on German units in the areas entered by the Allied forces, easing the Allied advance through France in August 1944.[63] According to a volume of the U.S. official history of the war,

In Brittany, southern France, and the area of the Loire and Paris, French Resistance forces greatly aided the pursuit to the Seine in August. Specifically, they supported the Third Army in Brittany and the Seventh U.S. and First French Armies in the southern beachhead and the Rhône valley. In the advance to the Seine, the French Forces of the Interior helped protect the southern flank of the Third Army by interfering with enemy railroad and highway movements and enemy telecommunications, by developing open resistance on as wide a scale as possible, by providing tactical intelligence, by preserving installations of value to the Allied forces, and by mopping up bypassed enemy positions.[64]

As regions of France were liberated, the FFI provided a ready pool of semi-trained manpower with which France could rebuild the French Army. Estimated to have a strength of 100,000 in June 1944, the strength of the FFI grew rapidly, doubling by July 1944, and reaching 400,000 by October 1944.[65] Although the amalgamation of the FFI was in some cases fraught with political difficulty, it was ultimately successful and allowed France to re-establish a reasonably large army of 1.3 million men by VE Day.[66]

Military strategy

Military strategy for the war as a whole was discussed among the Big Three powers, and especially among the United Kingdom and the United States, who were especially close with numerous calls and meetings held between U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In addition, the leaders of the Big Three met in conferences during the war to decide on overall military strategy.

The Arcadia Conference in December 1941, two weeks after Pearl Harbor, led to the Europe first strategy of defeating Germany before turning full attention to Japan and the Pacific.

The Tehran Conference in November 1943 had numerous objectives, and led to the commitment of the western Allies to open a second front in the war in the west.

The Yalta Conference in February 1945 was about the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. They also agreed to give France a zone of occupation in Germany carved out of the US and UK zones.

The Potsdam Conference was post-war mostly about occupation and demilitarization of Germany. It also established the need for trials of Nazi war criminals, with France playing a role.

Arcadia Conference

The "Europe first" strategy of Britain and the United States was decided at the Arcadia Conference, which was held in Washington, D.C., from December 22, 1941, to January 14, 1942.

It commenced two weeks after declarations of war on Japan by the United States, United Kingdom, after the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor and British possessions in southeast Asia. Following the declarations, Following the U.S. declaration, Japan's allies, Germany and Italy, declared war on the United States.

The conference brought together the top British and American military leaders, as well as Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt and their aides, in Washington from December 22, 1941, to January 14, 1942, and led to a series of major decisions that shaped the war effort in 1942–1943.

Arcadia was the first meeting on military strategy between Britain and the United States; it came two weeks after the American entry into World War II. The Arcadia Conference was a secret agreement unlike the much wider postwar plans given to the public as the Atlantic Charter, agreed between Churchill and Roosevelt in August 1941.

The main policy achievements of Arcadia included the decision for "Germany First" (or "Europe first"—that is, the defeat of Germany was the highest priority); the establishment of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, based in Washington, for approving the military decisions of both the US and Britain; the principle of unity of command of each theater under a supreme commander; drawing up measures to keep China in the war; limiting the reinforcements to be sent to the Pacific; and setting up a system for coordinating shipping. All the decisions were secret, except the conference drafted the Declaration by United Nations, which committed the Allies to make no separate peace with the enemy, and to employ full resources until victory.[67][68]

The Europe first strategy led two and a half years later to the invasions of France in Normandy and the Mediterranean coast.

Trident Conference

The decision to undertake a cross-channel invasion in 1944 was taken at the Trident Conference in Washington in May 1943. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, and General Bernard Montgomery was named as commander of the 21st Army Group, which comprised all the land forces involved in the invasion. The coast of Normandy of northwestern France was chosen as the site of the invasion, with the Americans assigned to land at sectors codenamed Utah and Omaha, the British at Sword and Gold, and the Canadians at Juno.

Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference[69] was a strategy meeting of the Big Three leaders Joseph Stalin, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy in Tehran. It was the first of the World War II conferences of the "Big Three" Allied leaders (the Soviet Union, the United States, and the United Kingdom). Although the three leaders arrived with differing objectives, the main outcome of the Tehran Conference was the Western Allies' commitment to open a second front against Nazi Germany.

Although the three leaders arrived with differing objectives, including concerns about Turkey, Iran, Yugoslavia, and Japan, the main outcome of the Tehran Conference was the Western Allies' commitment to open a second front against Nazi Germany in the West.

Campaigns

After the Fall of France, the battle to retake France began in Africa in November 1940. By September 1945, after the liberation of Paris and the southern France campaign and taking of Mediterranean ports in Marseille and Toulon, the country was largely liberated. The Allied Forces were driving into Germany from the west and the south. The liberation of France didn't finally end till the elimination of some pockets of German resistance along the Atlantic coast at the end of the war in May 1945.

Militarily, the liberation of France was part of the Western Front of World War II. Other than scattered raids in 1942 and 1943, the reconquest began in earnest in the summer of 1944 in parallel campaigns in the north and south of France. On 6 June 1944, the Allies began Operation Overlord (D-Day) in the largest seaborne invasion in history, establishing a beachhead in Normandy, landing two million men in northern France and opening another front in western Europe against Germany. In the south, the Allies launched Operation Dragoon on 15 August, opening a front on the Mediterranean. In four weeks, the Germans withdrew from southern France, retreating to Germany, and leaving French ports in Allied hands, resolving earlier supply problems in the south. Under the onslaught from both directions, the French Resistance organized a general uprising in Paris on 19 August, and on 25 August 1944 Paris was liberated. The Allied forces began to push towards the Rhine. Initial rapid advances in the North stretched lines of supply in the autumn, and the advance slowed. German counteroffensives in the winter of 1944-45 such as the Battle of the Bulge slowed but did not stop the Allied armies, some crossing the Rhine in February, with heavy German losses. By late March several Allied armies had crossed and began advancing rapidly into Germany, with the end of the war not far away. With France mostly liberated, a few pockets of German resistance remained until the end of the war in May 1945.

Gabon – November 1940

The Battle of Gabon resulted in the Free French Forces taking the colony of French Gabon and its capital, Libreville, from Vichy French forces. It was the only significant engagement in Central Africa during the war.

Algeria – November 1942

Operation Torch was a three-pronged Allied assault against Vichy régime targets in North Africa. The landing forces of Operation Torch came in at Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. Following Case Anton, French colonial governors had found themselves taking orders from the German military administration, and did so with varying degrees of enthusiasm. A few colonies such as French India pragmatically agreed that they did not wish to tangle with neighboring British colonies, which were larger and better-armed. Others had Axis neighbors, such as Tunisia or Somaliland. The American consul in Algiers believed that Vichy forces would welcome US forces.

Forces

A Western Task Force (aimed at Casablanca) was composed of American units, with Major General George S. Patton in command and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt heading naval operations. This Western Task Force consisted of the U.S. 3rd and 9th Infantry Divisions, and two battalions from the U.S. 2nd Armored Division — 35,000 troops in a convoy of over 100 ships. They were transported directly from the United States in the first of a new series of UG convoys providing logistical support for the North African campaign.

The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion,509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, and the U.S. 1st Armored Division—a total of 18,500 troops.

The Eastern Task Force—aimed at Algiers—was commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson and consisted of a brigade from the British 78th and the U.S. 34th Infantry Divisions, along with two British commando units (No. 1 and No. 6 Commandos), together with the RAF Regiment providing five squadrons of infantry and five Light anti-aircraft flights, totalling 20,000 troops. During the landing, ground forces were commanded by U.S. Major General Charles W. Ryder, of the 34th Division and naval forces were commanded by Royal Navy Vice-Admiral Sir Harold Burrough.

Tunisian campaign – November 1942

French Tunisia had been a protectorate of France since 1881 when it became part of France's colonial empire.

The Tunisian campaign took place from 17 November 1942 to 13 May 1943.

Corsica – 1943

Except for a brief period, Corsica had been under the control of France since the Treaty of Versailles (1768). In World War II, Corsica was occupied by the Kingdom of Italy from November 1942, through September 1943.[70] Italy initially occupied the island (as well as parts of France) as part of Nazi Germany's Operation Anton on 11 November 1942. At its peak, Italy had 85,000 troops on the island.[71] There was some native support among Corsican irredentists for the occupation. Benito Mussolini postponed the annexation of Corsica by Italy until after an assumed Axis victory in World War II, mainly because of German opposition to the irredentist claims.[72]

Although there was mild support for the occupation among collaborationists[73] and resistance was initially limited, it grew after the Italian invasion and by April 1943 became united, and was armed by airdrop and shipments by the Free French submarine Casabianca and establish some territorial control.[74]

After Mussolini's imprisonment in July 1943, German troops took over the occupation of Corsica. The Allied invasion of Italy began 3 September 1943, leading to Italy's surrender to the Allies, with the main invasion force landing in Italy on 9 September. The local resistance signaled an uprising for the same day, beginning the liberation of Corsica (Operation Vesuvius).

The Allies did not initially want such a movement, preferring to focus their forces on the invasion of Italy. However, in light of the insurrection, the Allies acquiesced to Free French troops landing on Corsica, starting with an elite detachment of the reconstituted French I Corps landing (again by the submarine Casabianca) at Arone near the village of Piana in northwest Corsica. This prompted the German troops to attack Italian troops in Corsica as well as the Resistance. The Resistance, and the Italian 44 Infantry Division Cremona and 20 Infantry Division Friuli engaged in heavy combat with the German Sturmbrigade Reichsführer SS. The Sturmbrigade was joined by the 90th Panzergrenadier Division and the Italian 12th Parachute Battalion of the 184th Parachute Regiment,[75] which were retreating from Sardinia through Corsica, from Bonifacio to the northern port of Bastia. There were now 30,000 German troops in Corsica withdrawing via Bastia. On 13 September elements of the 4th Moroccan Mountain Division landed in Ajaccio to try to stop the Germans. During the night of 3 to 4 October, the last German units evacuated Bastia, leaving behind 700 dead and 350 POWs.

Battle of Normandy – June 1944

Operation Overlord was launched on 6 June 1944 with troops landing in Normandy. Attacks by 1,200 planes preceded an amphibious assault by more than 5,000 vessels. Nearly 160,000 troops crossed the English Channel on 6 June.

The Battle of Normandy was won due to what is still today the largest ever military landing logistical operation; three million soldiers, mostly American, British, Canadian, [Australian contribution to the Battle of Normandy|Australian]] and Kiwis, but also other allied forces such as the Free French Forces, Polish Armed Forces in the West, Belgians, Czechoslovakian, Dutch and Norwegians crossed over the Channel from Britain.

Some of the German Army units they met in this operation were Ostlegionen, part of the German 243rd and 709th Static Infantry Divisions, near the Utah, Juno and Sword invasion beaches.[76]

Paris – August 1944

The Liberation of Paris was an urban military battle that took place over the period of a week from 19 August 1944 until the German garrison surrendered the French capital on 25 August 1944. Paris had been ruled by Nazi Germany since the signing of the Armistice on 22 June 1940, after which the Wehrmacht occupied northern and western France. The Germans surrendered Paris and the French took over, led by General de Gaulle, on 25 August 1944.

Background

As the final phase of Operation Overlord was still going on in August 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, was not considering the liberation of Paris to be a primary objective. The goal of the U.S. and British Armed Forces was to destroy the German forces, and end World War II in Europe, to allow the Allies to concentrate their efforts on the Pacific war.[77]

Uprising – 15 August

.jpg.webp)

As the French Resistance began to rise in Paris against the Germans on 15 August, Eisenhower stated that it was too early for an assault on Paris. he was also aware that Hitler had ordered the German military to completely destroy the city in the event of an Allied attack, and Paris was considered to have too great a value, culturally and historically, to risk its destruction.

On 15 August employees of the Paris Métro, the Gendarmerie, and Police went on strike; postal workers followed the next day. They were soon joined by workers across the city, causing a general strike to break out on 18 August. Barricades began to appear on 20 August, with Resistance fighters organizing themselves to sustain a siege. Trucks were positioned, trees cut down, and trenches were dug in the pavement to free paving stones for consolidating the barricades.

Skirmishes reached their peak on 22 August, when some German units tried to leave their fortifications. At 09:00 on 23 August, under Choltitz's orders, the Germans opened fire on the Grand Palais, an FFI stronghold, and German tanks fired at the barricades in the streets. Adolf Hitler gave the order to inflict maximum damage on the city.[78]

Allied arrival – 24-25 August

The liberation began when the French Forces of the Interior—the military structure of the French Resistance—staged an uprising against the German garrison upon the approach of the US Third Army led by General George Patton. On the night of 24 August, elements of General Philippe Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division made their way into Paris and arrived at the Hôtel de Ville shortly before midnight. The next morning, 25 August, the bulk of the 2nd Armored Division and the US 4th Infantry Division and other allied units entered the city. Dietrich von Choltitz, commander of the German garrison and the military governor of Paris, surrendered to the French at the Hôtel Meurice, the newly established French headquarters. General Charles de Gaulle of the French Army arrived to assume control of the city.

It is estimated that between 800 and 1,000 Resistance fighters were killed during the Battle for Paris, and another 1,500 were wounded.[79]

German surrender – 25 August

Despite repeated orders from Adolf Hitler that the French capital be destroyed before being given up,[80] Dietrich von Choltitz, as commander of the German garrison and military governor of Paris, surrendered on 25 August at the Hôtel Meurice. He then signed the official surrender at the Paris Police Prefecture. Choltitz later described himself in Is Paris Burning? as the saviour of Paris, for not blowing it up before surrendering.[81]

The same day, Charles de Gaulle, President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic moved back into the War Ministry and made a rousing speech to the crowd from the Hôtel de Ville. The day after de Gaulle's speech, General Leclerc's 2nd Armored Division paraded down the Champs-Élysées, while de Gaulle marched down the boulevard and entered the Place de la Concorde. On 29 August, the U.S. Army's 28th Infantry Division paraded 24-abreast up the Avenue Hoche to the Arc de Triomphe, then down the Champs Élysées, greeted by joyous crowds.[82]

The uprising in Paris gave the newly established Free French government and its president, Charles de Gaulle, enough prestige and authority to establish a provisional French Republic, replacing the fallen Vichy regime),[83] which had fled into exile.

Southern France – August 1944

Planning and goals

When first planned, the campaign in southern France and the landings in Normandy were to take place simultaneously—Operation Overlord in Normandy, and "Anvil" (as the southern campaign was originally called) in the south of France. A dual landing was soon recognized to be impossible; the southern campaign was postponed. The ports in Normandy had insufficient capacity to handle Allied military supply needs and French generals under de Gaulle pressed for a direct attack on southern France with the participation of French troops. Despite objections by Churchill, the operation was authorized by the Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff on 14 July and scheduled for 15 August.[84][85][86]

The goal of the southern France campaign, now known as "Operation Dragoon" was to secure the vital ports on the French Mediterranean coast and pressure German forces with another front. The US VI Corps landed on the beaches of the French Riviera (Côte d'Azur) on 15 August 1944 shielded by a large naval task force, followed by several divisions of French Army B. They were opposed by the scattered forces of the German Army Group G, which had been weakened by the relocation of its divisions to other fronts and the replacement of its soldiers with third-rate Ostlegionen outfitted with obsolete equipment.

Objectives and forces

The chief objectives of Operation Dragoon were the important French ports of Marseille and Toulon. The Western Naval Task Force was formed under the command of Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt to carry the U.S. 6th Army Group to the shore. The 6th Army Group was formed in Corsica and activated on 1 August.[87] The main ground force for the operation was the US Seventh Army commanded by Alexander Patch, followed by the French Army B under command of General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny.[88] The French Resistance played a major role in the fighting. As the Allies advanced into France, the Resistance evolved from a guerilla fighting force to a semiorganized army called French Forces of the Interior (FFI).[89] The Allied ground and naval forces were supported by a fleet of 3470 planes, mostly stationed on Corsica and Sardinia.[90]

They were opposed by German Army Group G (Heeresgruppe G), including the 19th Army, led by Friedrich Wiese. The Army was understrength, most of the units having been sent north earlier.[91][92] The units were spread thinly, made up of second rate units from eastern Europe with low morale and poor equipment.[91][93] The coastal defenses had been improved by the Vichy regime and later improved by the Germans after they took over in November 1942.[94]

Preparations

On 14 August, preliminary landings took place in the Hyères Islands by the First Special Service Force, a joint U.S.-Canadian special-forces unit, to secure a staging area and for amphibious landing training. After sporadic resistance, driving the German garrison to the western part of the island, the Germans surrendered on 17 August. The Force transferred to the mainland, becoming part of the First Airborne Task Force. Meanwhile, French commandos were active to the west in Operation Romeo and Operation Span.[95][96]

Hindered by Allied air supremacy and a large-scale uprising by the French Resistance, the weak German forces were swiftly defeated. The Germans withdrew to the north through the Rhône valley, to establish a stable defense line at Dijon. Allied mobile units were able to overtake the Germans and partially block their route at the town of Montélimar. The ensuing battle led to a stalemate, with neither side able to achieve a decisive breakthrough, until the Germans were finally able to complete their withdrawal and retreat from the town. While the Germans were retreating, the French managed to capture the important ports of Marseille and Toulon, putting them into operation soon after.

The Germans were not able to hold Dijon and ordered a complete withdrawal from Southern France. Army Group G retreated further north, pursued by Allied forces. The fighting ultimately came to a stop at the Vosges mountains, where Army Group G was finally able to establish a stable defense line. After meeting with the Allied units from Operation Overlord, the Allied forces were in need of reorganizing and, facing stiffened German resistance, the offensive was halted on 14 September. Operation Dragoon was considered a success by the Allies. It enabled them to liberate most of Southern France in just four weeks while inflicting heavy casualties on the German forces, although a substantial part of the best German units were able to escape. The captured French ports were put into operation, allowing the Allies to solve their supply problems soon after.

Pockets of German resistance – to May 1945

The pocket of La Rochelle was a zone of German resistance at the end of the Second World War. It was made up of the city of La Rochelle, the submarine base at La Pallice, of the Ile de Ré and of most of Ile d'Oléron (the southern part of the island was part of the Royan pocket).

Victory – 7 May 1945

Victory in Europe was achieved on 7 May 1945, and was enshrined and is celebrated as V-E Day.

Adolf Hitler, the Nazi leader, had committed suicide on 30 April during the Battle of Berlin and Germany's surrender was authorised by his successor, Reichspräsident Karl Dönitz. The administration headed by Dönitz was known as the Flensburg Government. The act of military surrender was first signed at 02:41 on 7 May in SHAEF HQ at Reims,[97] and a slightly modified document, considered the definitive German Instrument of Surrender, was signed on 8 May 1945 in Karlshorst, Berlin at 21:20 local time.

The German High Command will at once issue orders to all German military, naval and air authorities and to all forces under German control to cease active operations at 23.01 hours Central European time on 8 May 1945...

— German Instrument of Surrender, Article 2

Upon the defeat of Germany, celebrations erupted throughout the western world, especially in the UK and North America. More than one million people celebrated in the streets throughout the UK to mark the end of the European part of the war. In London, crowds massed in Trafalgar Square and up the Mall to Buckingham Palace, where King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by their daughters and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, appeared on the balcony of the palace before the cheering crowds. Churchill went from the palace to Whitehall where he addressed another large crowd:[98]

God bless you all. This is your victory. In our long history, we have never seen a greater day than this. Everyone, man or woman, has done their best.

At this point he asked Ernest Bevin to come forward and share the applause. Bevin said: "No, Winston, this is your day", and proceeded to conduct the people in the singing of For He's a Jolly Good Fellow.[98] Later, Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II) and her sister Princess Margaret were allowed to wander incognito among the crowds and take part in the celebrations.[99]

In the United States, the event coincided with President Harry Truman's 61st birthday.[100] He dedicated the victory to the memory of his predecessor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had died of a cerebral hemorrhage less than a month earlier, on 12 April.[101] Flags remained at half-staff for the remainder of the 30-day mourning period.[102][103] Truman said of dedicating the victory to Roosevelt's memory and keeping the flags at half-staff that his only wish was "that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day".[101] Later that day, Truman said that the victory made it his most enjoyable birthday.[100] Great celebrations took place in many American cities, especially in New York's Times Square.[104]

Aftermath

By the Autumn of 1944, Paris and the northern part of France were in Allied hands following operation Overlord (D-day), and the southern part of France was free in the wake of the success of Operation Dragoon. Excepting some Atlantic pockets, the Allies were in full control of France, freeing their military forces to push eastward across the Rhine into Germany and towards Berlin.

Meanwhile, liberation of most of metropolitan France unleashed several other overlapping events. The Provisional Government, already in existence since June 1944, moved back to the capital after Paris was liberated in late August, where it piloted an orderly transition back to republican government. The Vichy Regime held its last meeting on 17 August 1944, before fleeing into exile in Sigmaringen, Germany. Within France, there was a wave of assaults, extra-judicial executions, and public humiliations of suspected collaborators known as the épuration sauvage, followed by a series of legal purges ordered by courts set up for the purpose. The first free municipal elections since before the war were organized by the Provisional Government in May 1945, and the new Constitution of the Fourth French Republic was accepted in October 1946.

Advance to the Rhine

Fighting on the Western front seemed to stabilize, and the Allied advance stalled in front of the Siegfried Line (Westwall) and the southern reaches of the Rhine. Starting in early September, the Americans began slow and bloody fighting through the Hurtgen Forest ("Passchendaele with tree bursts"—Hemingway) to breach the Line.

The port of Antwerp was liberated on 4 September by the British 11th Armoured Division. However, it lay at the end of the long Scheldt Estuary, and so it could not be used until its approaches were clear of heavily fortified German positions. The Breskens pocket on the southern bank of the Scheldt was cleared with heavy casualties by allied forces in Operation Switchback, during the Battle of the Scheldt. This was followed by a tedious campaign to clear a peninsula dominating the estuary, and finally, the amphibious assault on Walcheren Island in November. The campaign to clear the Scheldt Estuary along with Operation Pheasant was a decisive victory for the Allies, as it allowed a greatly improved delivery of supplies directly from Antwerp, which was far closer to the front than the Normandy beaches.

In October the Americans decided that they could not just invest Aachen and let it fall in a slow siege, because it threatened the flanks of the U.S. Ninth Army. As it was the first major German city to face capture, Hitler ordered that the city be held at all costs. In the resulting battle, the city was taken, at a cost of 5,000 casualties on both sides, with an additional 5,600 German prisoners.

South of the Ardennes, American forces fought from September until mid-December to push the Germans out of Lorraine and from behind the Siegfried Line. The crossing of the Moselle River and the capture of the fortress of Metz proved difficult for the American troops in the face of German reinforcements, supply shortages, and unfavorable weather. During September and October, the Allied 6th Army Group (U.S. Seventh Army and French First Army) fought a difficult campaign through the Vosges Mountains that was marked by dogged German resistance and slow advances. In November, however, the German front snapped under the pressure, resulting in sudden Allied advances that liberated Belfort, Mulhouse, and Strasbourg, and placed Allied forces along the Rhine River. The Germans managed to hold a large bridgehead (the Colmar Pocket), on the western bank of the Rhine and centered around the city of Colmar. On 16 November the Allies started a large scale autumn offensive called Operation Queen. With its main thrust again through the Hürtgen Forest, the offensive drove the Allies to the Rur River, but failed in its core objectives to capture the Rur dams and pave the way towards the Rhine. The Allied operations were then succeeded by the German Ardennes offensive.

End of Vichy

Under pressure of the advancing Allied forces, Pierre Laval held the last government council on 17 August 1944, with five ministers.[105] With permission from the Germans, he attempted to call back the prior National Assembly with the goal of giving it power[106] and thus impeding the communists and de Gaulle.[107] So he obtained the agreement of German ambassador Otto Abetz to bring Édouard Herriot, (President of the Chamber of Deputies) back to Paris.[107] But ultra-collaborationists Marcel Déat and Fernand de Brinon protested this to the Germans, who changed their minds[108] and took Laval to Belfort[109] along with the remains of his government, "to assure its legitimate security", and arrested Herriot.[110]

On 20 August 1944 Pierre Laval was taken to Belfort[109] by the Germans along with the remains of his government, "to assure its legitimate security". Vichy head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain was conducted against his will to Belfort on 20 August 1944. A governmental commission directed by Fernand de Brinon was proclaimed on 6 September.[111] On 7 September, they were taken ahead of the advancing Allied Forces out of France to the town of Sigmaringen, where they arrived on the 8th, where other Vichy officials were already present.[112] Rather than resign his post, Pétain wrote in a letter to the French "I am, and remain morally, your leader", but this was a fiction.

Hitler requisitioned the Sigmaringen Castle for use by top officials. This was then occupied and used by the Vichy government-in-exile from September 1944 to April 1945. Pétain resided at the Castle, but refused to cooperate, and kept mostly to himself,[111] and ex-Prime Minister Pierre Laval also refused.[113] Despite the efforts of the collaborationists and the Germans, Pétain never recognized the Sigmaringen Commission.[114] The Germans, wanting to present a facade of legality, enlisted other Vichy officials such as Fernand de Brinon as president, along with Joseph Darnand, Jean Luchaire, Eugène Bridoux, and Marcel Déat.[115]

On 7 September 1944,[116] fleeing the advance of Allied troops into France, while Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime ceased to exist, a thousand French collaborators (including a hundred officials of the Vichy regime, a few hundred members of the French Militia, collaborationist party militants, and the editorial staff of the newspaper Je suis partout) but also waiting-game opportunists[lower-alpha 4] also went into exile in Sigmaringen.

The commission had its own radio station (Radio-patrie, Ici la France) and official press (La France, Le Petit Parisien), and hosted the embassies of the Axis powers: Germany, Italy and Japan. The population of the enclave was about 6,000, including known collaborationist journalists, the writers Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, the actor Robert Le Vigan, and their families, as well as 500 soldiers, 700 French SS, prisoners of war and French civilian forced laborers.[117] Inadequate housing, insufficient food, promiscuity among the paramilitaries, and lack of hygiene facilitated the spread of numerous illnesses including flu and tuberculosis) and a high mortality rate among children, ailments that were treated as best they could by the only two French doctors, Doctor Destouches, alias Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Bernard Ménétrel.[116]

On 21 April 1945 General de Lattre ordered his forces to take Sigmaringen. The end came within days. By the 26th, Pétain was in the hands of French authorities in Switzerland,[118] and Laval had fled to Spain.[113] Brinon,[119] Luchaire, and Darnand were captured, tried, and executed by 1947. Other members escaped to Italy or Spain.

Justice and retribution

Extrajudicial purges

Immediately following the liberation, France was swept by a wave of executions, public humiliations, assaults and detentions of suspected collaborators, known as the épuration sauvage (wild purge).[120] This period succeeded the German occupational administration but preceded the authority of the French Provisional Government, and consequently lacked any form of institutional justice.[120] Approximately 9,000 were executed, mostly without trial as summary executions,[120] notably including members and leaders of the pro-Nazi milices. In one case, as many as 77 milices members were summarily executed at once.[121] An inquest into the issue of summary executions launched by Jules Moch, the Minister of the Interior, came to the conclusion that there were 9,673 summary executions. A second inquest in 1952 separated out 8,867 executions of suspected collaborators and 1,955 summary executions for which the motive of killing was not known, giving a total of 10,822 executions. Head-shaving as a form of humiliation and shaming was a common feature of the purges,[122] and between 10,000 and 30,000 women accused of having collaborated with the Germans or having had relationships with German soldiers or officers were subjected to the practice,[123] becoming known as les tondues (the shorn).[124]

Legal purge

The official épuration légale ("legal purge") began following a June 1944 decree that established a three-tier system of judicial courts:[125] a High Court of Justice which dealt with Vichy ministers and officials; Courts of Justice for other serious cases of alleged collaboration; and regular Civic Courts for lesser cases of alleged collaboration.[120][126] Over 700 collaborators were executed following proper legal trials. This initial phase of the purge trials ended with a series of amnesty laws passed between 1951 and 1953[127] which reduced the number of imprisoned collaborators from 40,000 to 62,[128] and was followed by a period of official "repression" that lasted between 1954 and 1971.[127]

Reliable statistics of the death toll do not exist. At the low end, one estimate is that approximately 10,500 were executed, before and after liberation. "The courts of Justice pronounced about 6,760 death sentences, 3,910 in absentia and 2,853 in the presence of the accused. Of these 2,853, 73 percent were commuted by de Gaulle, and 767 carried out. In addition, about 770 executions were ordered by the military tribunals. Thus the total number of people executed before and after the Liberation was approximately 10,500, including those killed in the épuration sauvage",[120] notably including members and leaders of the milices. US forces put the number of "summary executions" following liberation at 80,000. The French Minister of the Interior in March 1945 claimed that the number executed was 105,000.[129]

Elections of May 1945

The French municipal elections of 1945 were held in two rounds on 29 April and 13 May 1945. These were the first elections since the liberation of France and the first in which women could vote.[lower-alpha 5] The elections did not take place in four departments (Bas-Rhin, Haut-Rhin, Moselle and Territory of Belfort) as recent fighting had prevented the creation of electoral lists. In Moselle, they were postponed to 23 and 30 September at the same time as the cantonal elections because the end of the fighting was too close. These difficulties made it very difficult to compile electoral lists that included women, and there were very few by-elections before these historic dates.

Election context

While the war was not yet officially over (the German surrender of May 8, 1945 was signed between the two rounds), the elections took place in a difficult political and social situation: the economic situation remained very precarious, not all the prisoners of war had returned, and many scores were being settled in local political life. (See section Justice and retribution below.)

These elections were the first test for the validity of the provisional institutions that had emerged from the Resistance.

The electoral system in force was the two-round majority system, except in Paris where elections were held under the proportional system. This election was also marked by the participation of women for the first time in France. On April 21, 1944, the right to vote had been granted to women by the French Committee of National Liberation ,[lower-alpha 5] and confirmed by the ordinance of October 5 under the Provisional Government of the French Republic. Given the absence of 2 1/2 million prisoners of war, deportees, Compulsory Work Service (Service du travail obligatoire) workers, and the ban on voting by career soldiers, the electorate in this election was composed of up to 62% women (although the figure of 53% is also cited). Despite the novelty of women voters, there was no particular media reaction, partly because of the difficulties related to the immediate post-war period which were of greater concern, such as returned deportees, prisoner camps, food rationing, and so on.

The referendum proposed to the French by the Provisional Government (GPRF) contained two questions. The first one proposed the drafting of a new Constitution and, consequently, the abandonment of the institutions of the Third Republic. Charles de Gaulle advocated for its support, as did all political parties, excepting the radicals, who remained faithful to the Third Republic. On 21 October 1945, 96 per cent of the French voted "yes" on the first question of the referendum in favor of changing the institutions: the Assembly elected that day would thus be constituent.

The second referendum question concerned the powers of this Constituent Assembly. Fearing a preponderance of communists in control over it, which would allow them to legally install a power of their own choice, General de Gaulle provided a text strictly limiting its prerogatives: its duration was limited to seven months, the constitutional plans it would draft would be submitted to popular referendum, and finally it could only bring down the government by a motion of censure voted by an absolute majority of its members. Most parties supported de Gaulle in advocating a "yes" vote, including the Popular Republican Movement (MRP), the socialists, and the moderates, while the communists and radicals pushed for "no". Nevertheless, 66 per cent of the electorate approved of limiting the powers of the Assembly by voting "yes" in the referendum.[130]

Provisional Government of the French Republic

The Provisional Government of the French Republic was the successor organization to the French Committee of National Liberation. It served as an interim government of Free France between 1944 and 1946, and lasted until the establishment of the French Fourth Republic. Its founding marked the official restoration and re-establishment of a provisional French Republic, assuring continuity with the defunct French Third Republic which dissolved itself in 1940 with the advent of the Vichy regime.

The PGFR was created by the Committee of National Liberation on 3 June 1944, the day before de Gaulle arrived in London from Algiers on Winston Churchill's invitation, and three days before D-day. It moved back to Paris after the liberation of the capital, where its war and foreign policy goals were to secure a French occupation zone in Germany and a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council. This was assured through a large military contribution on the western front.

Besides war and foreign policy goals, its principal mission was to prepare the transition to a new constitutional order, that utlimately resulted in the Fourth Republic. It also made several important reforms and political decisions, such as granting women the right to vote[lower-alpha 5], founding the École nationale d'administration, and laying the groundwork of social security in France.

With regard to transition to a new Republic, the GPRF organized the 1945 French legislative election for 21 October 1945, drew up a Constitution to present to the public for approval, and organized the Constituional referendum on 13 October 1946 in which it was adopted by the voters, thus bringing into existence the French Fourth Republic.

Fourth Republic

With most of the political class discredited and containing many members who had more or less collaborated with Nazi Germany, Gaullism and communism became the most popular political forces in France.

The Provisional Government (GPRF) ruled from 1944 to 1946, with de Gaulle in charge. Meanwhile, negotiations took place over the proposed new constitution, which was to be put to a referendum. De Gaulle advocated a presidential system of government, and criticized the reinstatement of what he pejoratively called "the parties system". He resigned in January 1946 and was replaced by Felix Gouin of the French Section of the Workers' International (socialists; SFIO). Ultimately, only the French Communist Party (PCF) and the socialist SFIO supported the draft constitution, which envisaged a form of government based on unicameralism; but this was rejected in the referendum of 5 May 1946.

For the 1946 elections, the Rally of Left Republicans (RGR), which encompassed the Radical Party, the Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance and other conservative parties, unsuccessfully attempted to oppose the Christian democrat and socialist MRP–SFIO–PCF alliance. The new constituent assembly included 166 MRP deputies, 153 PCF deputies and 128 SFIO deputies, giving the tripartite alliance an absolute majority. Georges Bidault of the MRP replaced Felix Gouin as the head of government.

A new draft of the Constitution was written, which this time proposed the establishment of a bicameral form of government. Leon Blum of the SFIO headed the GPRF from 1946 to 1947. After a new legislative election in June 1946, the Christian democrat Georges Bidault assumed leadership of the Cabinet. Despite De Gaulle's so-called discourse of Bayeux of 16 June 1946 in which he denounced the new institutions, the new draft was approved by 53% of voters voting in favor (with an abstention rate of 31%) in the referendum of 13 October 1946. This culminated in the establishment of the Fourth Republic two weeks later, an arrangement in which executive power essentially resided in the hands of the President of the Council (the prime minister). The President of the Republic was given a largely symbolic role, although he remained chief of the French Army and as a last resort could be called upon to resolve conflicts.

Impact

Demographic

France's losses during World War II totaled 600,000 people (1.44% of the population), including 210,000 military deaths from all causes, and 390,000 civilian deaths due to military activity and crimes against humanity.[131] In addition they suffered 390,000 wounded military.[132]

Jewish life and society at large had to adjust to a reduced population of French Jews. Of the 340,000 Jews living in metropolitan/continental France in 1940, more than 75,000 were deported to death camps by the Vichy regime, where about 72,500 were killed.[133][134][135]

Economic

After a period of penury and hardship, the economy took off, beginning what became known as the "Trente glorieuses" (30 glorious years).

Monnet plan