Public Health Emergency of International Concern

A Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) is a formal declaration by the World Health Organization (WHO) of "an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response", formulated when a situation arises that is "serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected", which "carries implications for public health beyond the affected state's national border" and "may require immediate international action".[1] Under the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), states have a legal duty to respond promptly to a PHEIC.[2][3] The declaration is publicized by an IHR Emergency Committee (EC) of international experts,[4] which was developed following the SARS outbreak in 2002–03.[5]

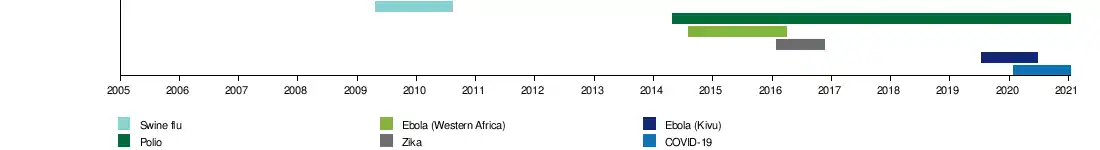

Since 2009, there have been six PHEIC declarations:[6][7] the 2009 H1N1 (or swine flu) pandemic, the 2014 polio declaration, the 2014 outbreak of Ebola in Western Africa, the 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic,[8] the 2018–20 Kivu Ebola epidemic,[9] and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[10] The recommendations are temporary and require reviews every three months.[1]

SARS, smallpox, wild type poliomyelitis, and any new subtype of human influenza are automatically PHEICs and thus do not require an IHR decision to declare them as such.[11] A PHEIC is not confined to infectious diseases, and may cover an emergency caused by exposure to a chemical agent or radioactive material.[12] In any case within its ambit, it is a "call to action" and "last resort" measure.[13]

Background

Multiple surveillance and response systems exist worldwide for the early detection and effective response to contain the spread of disease. Time delays still occur for two main reasons, however. The first is the delay between the first case and the confirmation of the outbreak by the healthcare system, allayed by good surveillance via data collection, evaluation, and organisation. The second is when there is a delay between the detection of the outbreak and widespread recognition and declaration of it as an international concern.[5] The declaration is promulgated by an Emergency Committee (EC) made up of international experts operating under the IHR (2005),[4] which was developed following the SARS outbreak of 2002/2003.[5] Between 2009 and 2016, there were four PHEIC declarations.[7] The fifth was the 2018–20 Kivu Ebola epidemic which was announced on 17 July 2019.[9] The sixth is the 2019–20 COVID-19 pandemic.[10] Under the 2005 International Health Regulations (IHR), States have a legal duty to respond promptly to a PHEIC.[2]

Definition

PHEIC is defined as;

an extraordinary event which is determined to constitute a public health risk to other States through the international spread of disease and to potentially require a coordinated international response.[14]

This definition designates a public health crisis of potentially global reach and implies a situation that is "serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected", which may necessitate immediate international action.[14][15]

It is a "call to action" and "last resort" measure.[13]

Reporting a potential concern

WHO Member States have 24 hours within which to report potential PHEIC events to the WHO.[11] It does not have to be a member State that reports a potential outbreak, hence reports to the WHO can also be received informally.[16] Under the IHR (2005), ways to detect, evaluate, notify and report events were ascertained by all countries in order to avoid PHEICs. The response to public health risks was also decided.[13]

The IHR decision algorithm assists WHO Member States in deciding whether a potential PHEIC exists and the WHO should be notified. The WHO should be notified if any two of the four following questions are affirmed:[11]

- Is the public health impact of the event serious?

- Is the event unusual or unexpected?

- Is there a significant risk for international spread?

- Is there a significant risk for international travel or trade restrictions?

The PHEIC criteria include a list of diseases that are always notifiable.[16] SARS, smallpox, wild type poliomyelitis and any new subtype of human influenza are always a PHEIC and do not require an IHR decision to declare them as such.[14]

Large scale health emergencies which attract public attention do not necessarily fulfill the criteria to be a PHEIC.[13] EC's were not convened for the cholera outbreak in Haiti, chemical weapons use in Syria or the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, for example.[12][17]

Further assessment is required for diseases which are prone to pandemics, including but not limited to cholera, pneumonic plague, yellow fever, and viral hemorrhagic fevers.[17]

A declaration of a PHEIC may appear as an economic burden to the state facing the epidemic. Incentives to declare an epidemic are lacking and the PHEIC can be seen as placing limitations on trade in countries that are already struggling.[13]

Emergency Committee

In order to declare a PHEIC, the WHO Director-General is required to take into account factors which include the risk to human health and international spread as well as advice from an internationally made up committee of experts, the IHR Emergency Committee (EC), one of which should be an expert nominated by the State within whose region the event arises.[1] Rather than being a standing committee, the EC is created ad hoc.[18]

Until 2011, the names of IHR EC members were not publicly disclosed; in the wake of reforms now they are. These members are selected according to the disease in question and the nature of the event. Names are taken from the IHR Experts Roster. The Director-General takes the EC's advice following their technical assessment of the crisis using legal criteria and a predetermined algorithm after a review of all available data on the event. Upon declaration, the EC then makes recommendations on what actions the Director-General and Member States should take to address the crisis.[18] The recommendations are temporary and require three-monthly reviews.[1]

Declarations

Summary of PHEIC declarations

2009 swine flu declaration

In the spring of 2009, a novel influenza A (H1N1) virus emerged. It was detected first in Mexico, North America and spread quickly across the US and the world.[19] On 26 April 2009,[20] more than one month after its first emergence,[5] the first PHEIC was declared when the H1N1 (or swine flu) pandemic was still in Phase Three.[2][21][22] On the same day, within three hours the WHO web site received almost two million visits, necessitating the pandemic's own dedicated pandemic influenza web site.[20] At the time H1N1 had been declared a PHEIC, it had so far occurred in only three countries.[5] Declaring H1N1 a PHEIC has therefore been argued as fueling public fear.[17] However, a 2013 study sponsored by the WHO estimated that although the H1N1 pandemic was similar in magnitude to seasonal influenza, it resulted in the loss of more life-years due to a shift toward mortality among persons less than 65 years of age.[23]

2014 polio declaration

The second PHEIC was the 2014 polio declaration, issued in May 2014 with the resurgence of wild polio after its near-eradication, deemed "an extraordinary event".[24][25]

Global eradication was deemed to be at risk with small numbers of cases in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria.[17]

In October 2019, continuing cases of wild polio in Pakistan and Afghanistan, in addition to new vaccine-derived cases in Africa and Asia, was reviewed and remains a PHEIC.[26] It was extended on 11 December 2019.[27]

2014 Ebola declaration

Confirmed cases of Ebola were being reported in Guinea and Liberia in March 2014 and Sierra Leone by May 2014. On Friday, 8 August 2014, following the occurrence of Ebola in the United States and Europe and with the already intense transmission ongoing in three other countries for months,[13] the WHO declared its third PHEIC in response to the outbreak of Ebola in Western Africa.[28] Later, one review showed that a direct impact of this epidemic on America escalated a PHEIC declaration.[5] It was the first PHEIC in a resource-poor setting.[13]

2016 Zika virus declaration

On 1 February 2016, the WHO declared its fourth PHEIC in response to clusters of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome in the Americas, which at the time were suspected to be associated with the ongoing 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic.[29] Later research and evidence bore out these concerns; in April, the WHO stated that "there is scientific consensus that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome."[30] This was the first time a PHEIC was declared for a mosquito‐borne disease.[17] This declaration was lifted on 18 November 2016.[31]

2018–20 Kivu Ebola declaration

In October 2018 and then later in April 2019, the WHO did not consider the 2018–20 Kivu Ebola epidemic to be a PHEIC.[32][33] The decision was controversial, with Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) responding with disappointment and describing the situation as "an Ebola gas can sitting in DRC that's just waiting for a match to hit it",[34] while the WHO panel were unanimous that declaring it a PHEIC would not give any added benefit.[34] The advice against declaring a PHEIC in October 2018 and April 2019, despite the criteria for doing so appearing to be met on both occasions has led to the transparency of the IHR EC coming into question. The language used in the statements for the Kivu Ebola epidemic has been noted to be different. In October 2018, the EC stated "a PHEIC should not be declared at this time". However, in the 13 previously declined proposals for declaring a PHEIC, the resultant statements quoted "the conditions for a PHEIC are not currently met" and "does not constitute a PHEIC". In April 2019, they stated that "there is no added benefit to declaring a PHEIC at this stage", a notion that is not part of the PHEIC criteria laid down in the IHR.[18][35]

After confirmed cases of Ebola in neighbouring Uganda in June 2019, Tedros Adhanom, the Director-General of the WHO, announced that the third meeting of a group of experts would be held on 14 June 2019 to assess whether the Ebola spread had become a PHEIC.[36][37] The conclusion was that while the outbreak was a health emergency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the region, it does not meet all the three criteria for a PHEIC.[38] Despite the number of deaths reaching 1,405 by 11 June 2019 and 1,440 by 17 June 2019, the reason for not declaring a PHEIC was that the overall risk of international spread was deemed to be low, and the risk of damaging the economy of the DRC high.[39] Adhanom also stated that declaring a PHEIC would be an inappropriate way to raise money for the epidemic.[40] Following a visit to the DRC in July 2019, Rory Stewart, the UK's DfID minister, called for the WHO to declare it an emergency.[41]

Acknowledging a high risk of spread to the capital of North Kivu, Goma, a call for a PHEIC declaration was published on 10 July 2019 in the Washington Post by Daniel Lucey and Ron Klain (the former US Ebola response coordinator). They stated that "in the absence of a trajectory toward extinguishing the outbreak, the opposite path—severe escalation—remains possible. The risk of the disease moving into nearby Goma, Congo—a city of 1 million residents with an international airport—or crossing into the massive refugee camps in South Sudan is mounting. With a limited number of vaccine doses remaining, either would be a catastrophe".[42][43] Four days later, on 14 July 2019, a case of Ebola was confirmed in Goma, which has an international airport and a highly mobile population. Subsequently, the WHO announced a reconvening of a fourth EC meeting on 17 July 2019, when they officially announced it "a regional emergency, and by no means a global threat" and declared it as a PHEIC, without restrictions on trade or travel.[44][45] In response to the declaration, the president of the DRC, together with an expert committee led by a virologist, took responsibility for directly supervising action, while in protest of the declaration, health minister, Oly Ilunga Kalenga resigned.[46] A review of the PHEIC had been planned at a fifth meeting of the EC on 10 October 2019[47] and on 18 October 2019 it remained a PHEIC[9] until 26 June 2020 when it was decided that the situation no longer constitutes a PHEIC.[48]

2019–20 COVID-19 declaration

.png.webp)

On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak of COVID-19, centered on Wuhan in central China, a PHEIC.[10][49]

On the date of the declaration there were 7,818 cases confirmed globally, affecting 19 countries in five of the six WHO regions.[50][51] Previously, the WHO had held EC meetings on 22 and 23 January 2020 regarding the coronavirus pandemic,[52][53][54] but it was determined that it was too early to declare a PHEIC at that time given the lack of necessary data and the (then) scale of global impact.[55][56] The WHO recognized the spread of COVID-19 as a pandemic on 11 March 2020.[57] Europe, Iran, US, South Korea, Latin America, and Japan reported a surging of cases and the total number quickly passed China.[58] The third meeting of the Emergency Committee convened on 30 April 2020,[59] the fourth on 31 July,[60] and the fifth on 29 October, all of which agreed that the outbreak continues to constitute a PHEIC.[61]

Response

In 2018, an examination of the first four declarations (2009–2016) showed that the WHO was noted to be more effective in responding to international health emergencies, and that the international system in dealing with these emergencies was "robust".[8]

Another review of the first four declarations, with the exception of wild polio, demonstrated that responses were varied. Severe outbreaks, or those that threatened larger numbers of people, did not receive a swift PHEIC declaration, and the study hypothesized that responses were quicker when American citizens were infected and when the emergencies did not coincide with holidays.[5]

Non-declarations

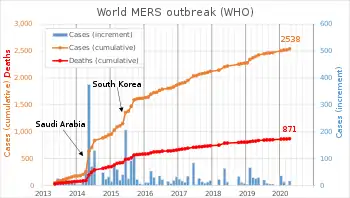

2013 MERS

PHEIC was not invoked with the Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak in 2013.[63][64] Originating in Saudi Arabia, MERS reached more than 24 countries and resulted in more than 580 deaths by 2015, although most cases were in hospital settings rather than sustained community spread. What constitutes a PHEIC has, as a result, been unclear.[12][6] As of May 2020, there has been 876 deaths.[6][65]

Non-infectious events

PHEIC are not confined to only infectious diseases. It may cover events caused by chemical agents or radioactive materials.[12]

The emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance may debatably constitute a PHEIC.[66][67][68]

See also

References

- WHO Q&A (19 June 2019). "International Health Regulations and Emergency Committees". WHO. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Renee Dopplick (29 April 2009). "Inside Justice | Swine Flu: Legal Obligations and Consequences When the World Health Organization Declares a 'Public Health Emergency of International Concern'". Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Collins, E. (2010). "13. Communication with the public". In Van-Tam, Jonathan; Sellwood, Chloe (eds.). Introduction to Pandemic Influenza. Wallingford, Oxford: CAB International. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-84593-578-8.

- "Strengthening health security by implementing the International Health Regulations (2005); About IHR". WHO. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Hoffman, Steven J.; Silverberg, Sarah L. (18 January 2018). "Delays in Global Disease Outbreak Responses: Lessons from H1N1, Ebola, and Zika". American Journal of Public Health. 108 (3): 329–333. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2017.304245. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 5803810. PMID 29345996.

- Mullen, Lucia; Potter, Christina; Gostin, Lawrence O.; Cicero, Anita; Nuzzo, Jennifer B. (1 June 2020). "An analysis of International Health Regulations Emergency Committees and Public Health Emergency of International Concern Designations" (PDF). BMJ Global Health. 5 (6): e002502. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002502. ISSN 2059-7908. PMID 32546587.

- Pillinger, Mara (2 February 2016). "WHO declared a public health emergency about Zika's effects. Here are three takeaways". Washington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2019.(subscription required)

- Hunger, Iris (2018). Coping with Public Health Emergencies of International Concern. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198828945.003.0004. ISBN 978-0191867422.(subscription required)

- WHO Statement (18 October 2019). "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 18 October 2019". www.who.int. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- WHO Statement (31 January 2020). "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". World Health Organisation. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Mark A. Hall; David Orentlicher; Mary Anne Bobinski; Nicholas Bagley; I. Glenn Cohen (2018). "8. Public Health Law". Health Care Law and Ethics (9th ed.). New York: Wolters Kluwer. p. 908. ISBN 978-1-4548-8180-3.

- Halabi, Sam F.; Crowley, Jeffrey S.; Gostin, Lawrence Ogalthorpe (2017). Global Management of Infectious Disease After Ebola. Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0190604882.

- Rull, Monica; Kickbusch, Ilona; Lauer, Helen (8 December 2015). "Policy Debate | International Responses to Global Epidemics: Ebola and Beyond". International Development Policy. 6 (2). doi:10.4000/poldev.2178. ISSN 1663-9375.

- WHO Regulations (2005). "Annex 2 of the International Health Regulations (2005)". WHO. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Exter, André den (2015). "Part VI Public Health; Chapter 1.1 International Health Regulations (2005)". International Health Law and Ethics: Basic Documents (3rd ed.). Maklu. p. 540. ISBN 978-9046607923.

- Davies, Sara E.; Kamradt-Scott, Adam; Rushton, Simon (2015). Disease Diplomacy: International Norms and Global Health Security. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421416489.

- Gostin, Lawrence O.; Katz, Rebeccas (June 2016). "The International Health Regulations: The Governing Framework for Global Health Security". The Milbank Quarterly. 94 (2): 264–313. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12186. PMC 4911720. PMID 27166578.

- Kamradt-Scott, Adam; Eccleston-Turner, Mark (1 April 2019). "Transparency in IHR emergency committee decision making: the case for reform". British Medical Journal Global Health. 4 (2): e001618. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001618. ISSN 2059-7908. PMC 6509695. PMID 31139463.

- Sara E. Davies; Adam Kamradt-Scott; Simon Rushton (2015). Disease Diplomacy: International Norms and Global Health Security. JHU Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4214-1648-9.

- Director-General (2009). Implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005), Report of the Review Committee on the Functioning of the International Health Regulations (2005) in relation to Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 (PDF). WHO. p. 118.

- Margaret Chan (25 April 2009). "Swine influenza". World Health Organization. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Swine flu illness in the United States and Mexico – update 2". World Health Organization. 26 April 2009. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- Simonsen, Lone; Spreeuwenberg, Peter; Lustig, Roger; Taylor, Robert J.; Fleming, Douglas M.; Kroneman, Madelon; Van Kerkhove, Maria D.; Mounts, Anthony W.; Paget, W. John; Hay, Simon I. (26 November 2013). "Global Mortality Estimates for the 2009 Influenza Pandemic from the GLaMOR Project: A Modeling Study". PLOS Medicine. 10 (11): e1001558. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001558. PMC 3841239. PMID 24302890.

- "WHO statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations Emergency Committee concerning the international spread of wild poliovirus". World Health Organization. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- MacKenzie, Debora (5 May 2014). "Global emergency declared as polio cases surge". New Scientist. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "News Scan: Polio in Pakistan". CIDRAP. 4 October 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "NaTHNaC – Polio: Public Health Emergency of International Concern". TravelHealthPro. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Ebola outbreak in West Africa declared a public health emergency of international concern". www.euro.who.int. 8 August 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- WHO (1 February 2016). WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee on Zika

- "Zika Virus Microcephaly And Guillain–Barré Syndrome Situation Report" (PDF). World Health Organization. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Fifth meeting of the Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (2005) regarding microcephaly, other neurological disorders and Zika virus". World Health Organization. WHO. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Green, Andrew (20 April 2019). "DR Congo Ebola outbreak not given PHEIC designation". The Lancet. 393 (10181): 1586. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30893-1. PMID 31007190.

- "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 12th April 2019". World Health Organization. 12 April 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- Cohen, Jon (12 April 2019). "Ebola outbreak in Congo still not an international crisis, WHO decides". Science Magazine. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- Lancet, The (25 May 2019). "Acknowledging the limits of public health solutions". The Lancet. 393 (10186): 2100. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31183-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 31226033.

- Hunt, Katie. "Ebola outbreak enters 'truly frightening phase' as it turns deadly in Uganda". CNN. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Gladstone, Rick (12 June 2019). "Boy, 5, and Grandmother Die in Uganda as More Ebola Cases Emerge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee for Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 14 June 2019". World Health Organization. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- Souchary, Stephanie (17 June 2019). "Ebola case counts spike again in DRC". CIDRAP. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- Soucheray, Stephanie (16 July 2019). "WHO will take up Ebola emergency declaration question for a fourth time". CIDRAP. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Wintour, Patrick (7 July 2019). "Declare Ebola outbreak in DRC an emergency, says UK's Rory Stewart". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Soucheray, Stephanie (11 July 2019). "Three more health workers infected in Ebola outbreak". CIDRAP. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Klain, Ronald A.; Lucey, Daniel (10 July 2019). "Opinion | It's time to declare a public health emergency on Ebola". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern". World Health Organization. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "Ebola outbreak declared public health emergency". BBC News. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- Schnirring, Lisa (22 July 2019). "DRC health minister resigns after government takes Ebola reins". CIDRAP. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Schnirring, Lisa; 9 October 2019. "Response resumes following security problems in DRC Ebola hot spot". CIDRAP. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "Final Statement on the 8th meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005)". www.who.int. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Ramzy, Austin; Jr, Donald G. McNeil (30 January 2020). "W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as the new Coronavirus Spreads". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- WHO Report (30 January 2020). "Novel Coronavirus(2019-nCoV): Situation Report-10" (PDF). WHO. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV)". WHO. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Fifield, Anna; Sun, Lena H. (23 January 2020). "Nine dead as Chinese coronavirus spreads, despite efforts to contain it". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Schnirring, Lisa (22 January 2020). "WHO decision on nCoV emergency delayed as cases spike". CIDRAP. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- WHO Statement (22 January 2020). "WHO Director-General's statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus". www.who.int. 22 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- Joseph, Andrew (23 January 2020). "WHO declines to declare China virus outbreak a global health emergency". STAT. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- WHO Statement (23 January 2020). "Statement on the meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus 2019 (n-CoV) on 23 January 2020". www.who.int. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 – 11 March 2020". World Health Organization. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "Operations Dashboard for ArcGIS". gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- "Statement on the third meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". www.who.int. 1 May 2020. Archived from the original on 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Statement on the fourth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19)". www.who.int. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "Statement on the fifth meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee regarding the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic". www.who.int. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- "WHO | MERS-CoV". WHO. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Robert Herriman (17 July 2013). "MERS does not constitute a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC): Emergency committee". The Global Dispatch. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- David R Curry (20 July 2013). "WHO Statement: Second Meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee concerning MERS-CoV – PHEIC Conditions Not Met | global vaccine ethics and policy". Center for Vaccine Ethics and Policy. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "WHO | Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) – Saudi Arabia". WHO. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- "Can the International Health Regulations apply to antimicrobial resistance?". medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 15 June 2019.

- Wernli, Didier; Haustein, Thomas; Conly, John; Carmeli, Yehuda; Kickbusch, Ilona; Harbarth, Stephan (April 2011). "A call for action: the application of The International Health Regulations to the global threat of antimicrobial resistance". PLOS Medicine. 8 (4): e1001022. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001022. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3079636. PMID 21526227.

- Kamradt-Scott, Adam (19 April 2011). "A Public Health Emergency of International Concern? Response to a Proposal to Apply the International Health Regulations to Antimicrobial Resistance". PLOS Medicine. 8 (4): e1001021. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001021. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 3080965. PMID 21526165.