Whitefield, Greater Manchester

Whitefield (pop. 23,283) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, Greater Manchester, England.[1] It lies on undulating ground above the Irwell Valley, along the south bank of the River Irwell, 3 miles (4.8 km) south-southeast of Bury, and 4.9 miles (7.9 km) to the north-northwest of the city of Manchester. Prestwich and the M60 motorway lie just to the south.

| Whitefield | |

|---|---|

All Saints' Church, Stand, a Waterloo church in Whitefield | |

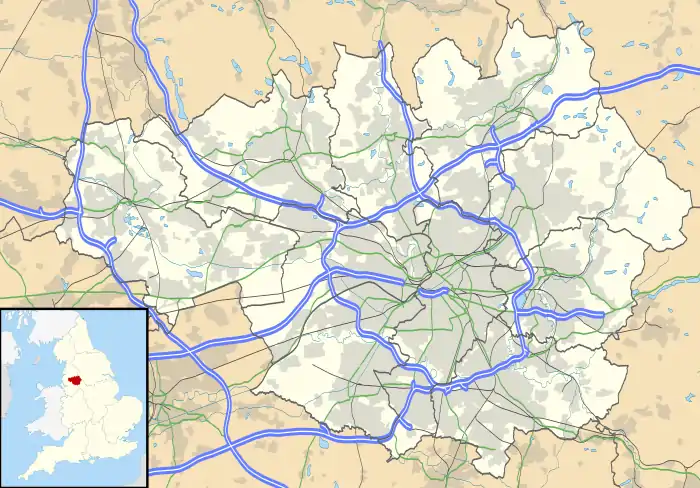

Whitefield Location within Greater Manchester | |

| Population | 23,283 (2001 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SD815065 |

| • London | 168 mi (270 km) SE |

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MANCHESTER |

| Postcode district | M45 |

| Dialling code | 0161 |

| Police | Greater Manchester |

| Fire | Greater Manchester |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Historically a part of Lancashire, Whitefield has been suggested as lying on the path of an ancient Roman road leading from Mamucium (Manchester) in the south to Bremetennacum (Ribchester) in the north. Throughout the Middle Ages, Whitefield was a division of the township of Pilkington, itself a part of the parish of Prestwich-cum-Oldham and hundred of Salford. Pilkington and Whitefield have historic associations with the Earls of Derby. Farming was the main industry of this rural area, with locals supplementing their incomes by hand-loom woollen weaving in the domestic system.

The urbanisation and development of Whitefield largely coincided with the Industrial Revolution. The name Whitefield is thought to derive from the medieval bleachfields used by Flemish settlers to whiten their woven fabrics, or else from the wheat crop once cultivated in the district. The construction of a major roads routed through the village facilitated Whitefield's expansion into a mill town during the mid-19th century. Whitefield was created a local government district in 1866, and was governed by a local board of health until 1894, when the area of the local board became an urban district.[1]

History

Toponymy

There are several theories for the origin of the place name, discussed in two local history publications. One, published in John Wilson's A History of Whitefield (1979), is that the name is derived from the Flemish weavers who used to lay out their fabrics to bleach in the sun (a process known as tentering). Although Wilson doubts this, believing it to be chronologically inaccurate, another theory relies on the fact that historically, Whitefield has been a farming community of open fields, and that the name is a corruption of "Wheat-fields". A third is that the name refers to a field of white flowers, evidenced by the existence of the area of Lily Hill Street.[2][3]

In Remains, Historical and Literary, Connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester (1861), the will of a John Rhodes describes leaving ownership of land in Whitefield Moore in Pilkington, to his son.[4]

Early history

In Elizabethan times, Whitefield was mostly moorland and until the 19th century existed, along with the districts of Ringley, Unsworth and Outwood, as part of the Manor of Pilkington.[2] In the 15th century the Pilkington family who, during the Wars of the Roses, supported the House of York, owned much of the land around the parish. Thomas Pilkington was at this time lord of many estates in Lancashire including the Manor of Bury.[5][6] In 1485 Richard III was killed in the Battle of Bosworth. The Earl of Richmond, representing the House of Lancaster, was crowned Henry VII. Sir William Stanley may have placed the crown upon his head. As a reward for the support of his family, on 27 October 1485 Henry made Thomas Stanley the Earl of Derby. Thomas Pilkington was attainted, and in February 1489 Earl Thomas was given many confiscated estates including those of Pilkington, which included the township of Pilkington, and Bury.[6][7] With their seat at Knowsley Hall, the Earls of Derby were by and large absentee landlords who appointed agents to manage their interests in the area, unlike the Earls of Wilton whose lands at Prestwich bordered the area and who oversaw events on their estate and dispensed charity from Heaton Hall.[8]

Over the centuries, hamlets grew at Besses o' th' Barn, Lily Hill, Four Lane Ends (now the junction around Moss Lane and Pinfold Lane[9]), Stand and Park Gate (now the junction around Park Lane and Pinfold Lane[9]) before being generalised into the area known as Whitefield.[2] Besses o' th' Barn was for some time known as Stone Pale and a small street of that name still exists.[10]

Governance

Whitefield was in 1853 a part of the township of Pilkington, in the parish of Prestwich-cum-Oldham.[11] Pilkington ceased to be a township in 1894 and at the same time part of the old boundary of Whitefield was absorbed by Radcliffe.[5] The realignment of the boundary with Radcliffe was due to the location of the Whitefield sewage works, which lying between Hillock and Parr Lane were in the wrong place to serve the Stand Lane area.[12] Whitefield had gained a local board in 1866, but after the dissolution of Pilkington township in 1894, Whitefield became an urban district with two wards, in the administrative county of Lancashire.[12]

A town hall was established in 1933 with the purchase of the house previously known as Underley, along with 3 acres (1.2 ha) of surrounding land. Before this the council chambers had been on Elms Street.[13] On 1 April 1974 Whitefield became an unparished area of the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, a local government district of the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester.

Geography

At 53°33′7″N 2°17′57″W (53.552°, −2.299°), Whitefield lies on the west side of the conjunction of the M60 and M66 motorways, and south of the River Irwell. The larger towns of Bury and Middleton lie to the north and east respectively.[14] For purposes of the Office for National Statistics, Whitefield forms part of the Greater Manchester Urban Area,[15] with Manchester city centre itself 4.9 miles (7.9 km) south-southeast of Whitefield.

Localities within Whitefield include Besses o' th' Barn, Hillock, Lily Hill, Park Lane, Stand and to the south of the M60 motorway and separated by it from the rest of the township is Kirkhams.[1][14]

The area has three medium-sized council housing estates (Hillock Estate, Elms Estate and Victoria Estate) which originally consisted of only council-owned properties. The Elms estate began to be constructed in the 1920s and was completed in the 1950s,[16] whilst the Hillock estate was conceived in the 1950s as an overspill estate for 8,000 people rehoused from the City of Manchester ward of Bradford, and Beswick, which were at the time undergoing housing clearances.[17] All three estates now include privately owned properties bought from council ownership under right-to-buy schemes, with the remainder at the Elms and Victoria managed by Six Town Housing,[18] an arms-length management organisation (ALMO) set up by the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, and at Hillock by Rivers Housing. Hillock is an attractive estate, and is often regarded as the most successful of all Manchester Corporation's many overspill developments.

Much of the area is made up of middle class suburban commuter developments, with some attractive older terraced housing too, especially around Lily Hill Street and Nipper Lane, and it also encompasses an area of larger properties surrounding Ringley Road and Park Lane. In recent years the area has seen new construction work on infill sites, and some residential development of brownfield sites more generally.

Demography

| Whitefield compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK census | Whitefield[19] | Bury (borough)[20] | England |

| Total population | 23,283 | 180,608 | 49,138,831 |

| White | 95.3% | 93.9% | 90.9% |

| Asian | 2.0% | 4.0% | 4.6% |

| Black | 0.7% | 0.5% | 2.3% |

In 2001, a census was taken of the United Kingdom, recording such details as people's age, ethnicity and religion. According to the Office for National Statistics, at the time of the census Whitefield had a population of 23,283. The 2001 population density was 13,460 inhabitants per square mile (5,197/km2), with a 100 to 91.3 female-to-male ratio.[21] Of those over 16 years old, 28.8% were single (never married) 44.6% married, and 8.4% divorced.[22] Whitefield's 9,849 households included 29.8% one-person, 36.8% married couples living together, 8.3% were co-habiting couples, and 11.4% single parents with their children.[23] Of those aged 16–74, 30.2% had no academic qualifications.[24]

As of the 2001 UK census, 74.3% of Whitefield's residents reported themselves as being Christian, 6.0% Jewish, 1.6% Muslim, 0.6% Hindu, 0.2% Buddhist and 0.1% Sikh. The census recorded 10.3% as having no religion, 0.1% had an alternative religion and 6.9% did not state their religion.[25]

Population change

Wilson, whilst not providing references to his own research, reports that the Hearth Tax Returns for Whitefield in 1666 show that there were 135 hearths.[26] Further, that the population numbered in 1714 a total of 740; that in 1789 it was 2,455; and in 1793 that it was 2,780.[27] Some of the population statistics which he quotes subsequently in his book, and presumably based upon the Official Census returns since 1901, do on occasion differ very slightly from those quoted below.[28]

| Population growth in Whitefield since 1901 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1939 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 |

| Population | 6,588 | 6,976 | 6,902 | 9,107 | 12,192 | 12,914 | 14,372 | 21,866 | 27,650 | 22,783 | 23,284 |

| Urban District 1901–1971[29] • Urban Subdivision 1981–2001[30][31][32] | |||||||||||

Economy

| Whitefield compared | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 UK Census | Whitefield[33] | Bury (borough)[34] | England |

| Population of working age | 16,824 | 151,445 | 35,532,091 |

| Full-time employment | 42.2% | 42.9% | 40.8% |

| Part-time employment | 11.7% | 12.0% | 11.8% |

| Self-employed | 7.5% | 8.1% | 8.3% |

| Unemployed | 2.7% | 2.8% | 3.3% |

| Retired | 15.1% | 13.3% | 13.5% |

In 1906 the following textile bleaching, dyeing and finishing businesses existed in Whitefield: John Brierley (at Spring Clough); W.E. Buckley & Co Ltd (Hollins Vale); R.& A. Chambers Ltd (Spring Waters); Thomas L. Livesey Ltd (Hollins Vale); Mark Fletcher & Sons Ltd (Moss Lane Mills, having been founded in Little Lever in 1854[35]); William Hampson (Besses); Kilner Croft Dyeing Co Ltd (Unsworth); Whitefield Velvet & Cord Dyeing Co Ltd (Crow Oak Works); and Philip Worrall (Hollins Vale).[36]

At the same time there were five cotton manufacturers in the area: J.G. Clayton and Nelson, Greenhalgh & Co (both at Albert Mills, on what was then Workhouse Lane); Lord, Frears & Bro. (Whitefield New Mill); Francis Mather (Whitefield Mill); and Worthington & Co (Victoria Mills, Unsworth). There were also two smallware manufacturers in the area, being Prestwich Smallware Co (on Hardmans Green, Besses) and the Victoria Smallware Co on Narrow Lane.[37] There were also at least two firms in the building trade: John Jackson & Son, builder and joiners, on Livesey Street; and F.M. & H. Nuttall, builders and stonemasons, who were on Moss Lane and later had their stoneyard adjoining the west side of Whitefield railway station.[38]

Whitefield's proximity to the M60 orbital motorway and city of Manchester has ensured that there are many small businesses and trading estates located locally. Whitefield has experienced several new commercial developments since the turn of the 21st century, for example with the replacement of Elms Shopping Precinct by a new gym and several new outlets and with a new Morrisons supermarket built in 2008 on land previously occupied by a public house, the bus station and a former retail premises which had seen several uses.

There used to be sweet factory on Stanley Road – Hall's, then arguably most famous for their "Mentho-Lyptus" product, sometimes spelled Menthol Lyptus – and there still is a large flooring company, Polyflor, in the Radcliffe New Road area; apart from these, most of the businesses are small.

According to the 2001 UK census, the industry of employment of residents of Whitefield aged 16–74 was 18.9% retail and wholesale, 13.7% manufacturing, 12.2% health and social work, 11.9% property and business services, 8.2% transport and communications, 7.6% education, 6.5% construction, 5.5% finance, 5.4 public administration, 4.3% hotels and restaurants, 0.7% energy and water supply, 0.5% agriculture, 0.1% mining and 4.7% other.[39] Compared with national figures, the town had a relatively high proportion of people working in finance, and low levels of people working in agriculture.[40] The census recorded the economic activity of residents aged 16–74, 2.1% students were with jobs, 3.2% students without jobs, 5.4% looking after home or family, 7.2% permanently sick or disabled and 3.0% economically inactive for other reasons.[33]

Transport

Public transport began some time in the early 19th century and in 1817 there were coach services being run through Whitefield between Manchester and Bury along Bury Old Road, which had been constructed in 1755.[10] However, Wilson speculates that these were probably mainly for freight and states that the Coach & Horses public house at Kirkhams was the coaching inn.[41]

Bury New Road –a turnpike road, taking an alternative route between Bury and Manchester – was constructed in 1827. Toll bars for this newly constructed road were built at Kersal Bar, Besses o' th' Barn, Stand Lane and Blackford Bridge.[42]

In the 1860s and 1870s transport between Whitefield and Manchester consisted of a four-horse bus running at hourly intervals, with local passenger stops at the Bay Horse Inn at Chapelfield and at the Church Inn in the centre of the town. The firm which operated this service was called Turner, after which Turner Street was named.[43]

The Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Tramways Company operated a service of trams pulled by a steam engine from 1883. These ran until the end of the century between Bury and Kersal Bar,[43] when they were replaced by electric trams leased by Salford Corporation between Bury and Manchester along both Bury Old Road and Bury New Road. The lease expired in 1926 and the trams between Whitefield and Manchester were then replaced by buses, also operated by Salford Corporation.[44] In the same year, Bury Corporation provided buses to operate from Whitefield to Bury.[45] A bus station, now demolished, was opened in 1931 just set back from the junction of Stanley Road and Bury New Road, behind the then Church Inn.[13]

In the 1920s the evening trams from Whitefield and Manchester had a letterbox fitted to their fronts, enabling letters to be posted at the tram stops in time to reach the last post collection at Manchester post sorting office.[44]

By 1905 electric trams were also running between Whitefield and Radcliffe along Radcliffe New Road.[43]

On 18 July 1872 the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (L&YR) gained an Act of Parliament to construct a railway between Manchester and Bury, via Whitefield and Prestwich. This opened in 1879 with a new station, known as Whitefield railway station. The L&YR line was electrified in 1916 for which a power station was constructed near the Manchester, Bolton & Bury Canal at nearby Clifton, with substations at Radcliffe and at Victoria Station, Manchester.[46][47] Electrification reduced the journey times between Manchester and Bury from 32 minutes to 24.[48] The line is now used by the Metrolink, upon which services commenced on 6 April 1992.[49] A station at nearby Besses o' th' Barn also serves the area, having been opened on 1 February 1933.[50]

All public transport is supervised by the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive.

Religion

The Five Mile Act of 1665 had made it an offence punishable by transportation for more than five people to congregate for worship other than in the manner prescribed by the Church of England, and for any nonconformist to minister within five miles (8 km) of any parish of which he had been a parson. The area of Stand was six miles (10 km) from Manchester, from Bolton and from Bury, which made it a suitable point at which nonconformists could legally meet. The specific catalyst for the meetings appears to have been the ejection of Thomas Pike from the living of Radcliffe due to his Puritan leanings; though he went to Blackley, those who agreed with his leanings began to meet at Stand, most probably at Old Hall, the house of Thomas Sergeant, after the family of whom the present Sergeant's Lane is named. By 1672 a barn belonging to William Walker had been licensed for preaching and in 1693 the Rev. Robert Easton, ejected Minister of Daresbury, near Warrington, became the first Minister of Stand Chapel. The building had been erected in that year on land obtained from the Trustees of Stand Grammar School and, indeed, the school was held in the chapel on weekdays.[51]

Whilst preaching the nonconformist position, Stand Chapel was not at this time Unitarian. The transition to Unitarianism was gradual, being completed in 1789 when the Rev. R. Aubrey determined to follow the doctrine (it was in fact illegal to call oneself a Unitarian until 1813). This doctrinal decision caused a split, with some of the congregation leaving to form Stand Independent Chapel on Stand Lane.[52]

Stand Unitarian Chapel was demolished and another built, capable of seating 400, in 1818.[53]

Stand All Saints' CofE Church, which was a so-called 'Waterloo Church', having been built to celebrate Napoleon's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815,[54] is located just outside the town centre. The site was given by the Earl of Derby and the first stone laid by the Earl of Wilton on 3 August 1822. Consecrated on 8 September 1826 by Dr Blomfield, Bishop of Chester, it was designed by Sir Charles Barry in the Gothic style of the 14th century.[55] The tower is 186 feet (57 m) in height.[11] The cost of the building was £14,987.[11][56] A clock was added to the tower in 1832 and then replaced in 1906.[57] The church forms the centrepiece of the All Saints' conservation area, designated by the local council in March 2004.[58]

Roman Catholics were of sufficient number by 1952 that they rented a room at the Liberal Club building, which was at that time on Morley Street; subsequently, in 1956, St Bernadette's Church was built on Manchester Road as their place of worship.[59] The building cost £22,446 and the foundation stone was laid on 26 March 1955; although the stone bears the name of Bishop H.V. Marshall it was in fact laid by the Vicar General, Monsignor J. Cunningham, due to the illness of the former.[60]

A few years later, and next door to St Bernadette's, a meetinghouse of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was erected.[59]

Other places of worship in the area include the New Jerusalem Church on Charles Street (there is another on Stand Lane), Whitefield Methodist Chapel, Besses United Reformed Church, two synagogues and a spiritualist church.

Whitefield Hebrew Congregation was built on land purchased from the Church of England, where originally a Church of England school had stood and which was demolished for the construction of the present synagogue.

In August 2010 it was reported that a planning application had been submitted to the Metropolitan Borough of Bury, on behalf of the Whitefield Hebrew Congregation, for the creation of a 4 miles (6.4 km) symbolic boundary, known as an eruv, around 1 square mile (2.6 km2) of Whitefield.[61] The construction of the eruv would allow the 700 Orthodox Jewish families living in the area to carry out activities normally prohibited on the Hebrew shabbat (sabbath), such as carrying keys, pushing prams and using wheelchairs.[61] Similar eruvim have already been created in a number of cities such as New York City, Antwerp and London. The Whitefield eruv would be the first to be constructed in the United Kingdom outside London.[61][62]

Culture, education media and sport

One local newspaper that covers the area of Whitefield (as well as neighbouring Prestwich and Radcliffe) is the Advertiser, (one of the GMWN Greater Manchester Weekly News newspapers) a weekly freesheet based in Salford. The other local paper (not distributed freely, door to door) is the Prestwich and Whitefield Guide.

Sedgley Park R.U.F.C. play their home matches at their Park Lane ground, and were in National Division One until the end of the 2008–09 season.

Besses o' th' Barn Band, and subsequently its associated boys' band, has existed in the area since at least 1818, at which time it had converted from a string band to a reed band. Its founders were John, James and Joseph Clegg – three brothers who were manufacturers of cotton products at Besses o' th' Barn – and for this reason it was for a time known as Clegg's Reed Band. Originally using a room called the mangle room, attached to the old barn at Besses which was pulled down in the 1880s,[63] it has had its headquarters on Moss Lane since 1884. At the peak of its fame in the early 1900s this band, by now using brass instruments, undertook numerous prestigious engagements, including world tours lasting well in excess of 12 months at a time.[64] Stand Cricket based on Hamilton Rd Founded in 1853 originally played were Stand Golf club are sited Played in the North West league Lancashire and Cheshire League Central Lancashire League Lancashire Country League and currently played the Greater Manchester League

Whitefield is the birthplace of Dodie Smith, author of the novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Public services

Whitefield's gas supply was originally made by the Radcliffe and Pilkington Gas Company, which had been founded in 1864.[65] This was purchased in 1921 by the Radcliffe and Little Lever Joint Gas Board. Gas was used by businesses, homes and also for street lighting.[66]

Around 1883 Thomas Thorp established an engineering business in Victoria Lane, complete with an astronomical observatory on its roof for his own use. He invented the penny-in-the-slot gas meter.[35]

Places of interest

- The Nature Trail

- Red Rose Forest – the second largest community forest in England.

- Irwell Sculpture Trail

References

- Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Place Names T to W, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 17 June 2008

- Wilson 1979, p. 1.

- Holt 1962

- Chetham Society 1861, p. 115.

- Farrer & Brownbill 1911, pp. 88–92.

- Coward 1983, pp. 13–14.

- Wilson 1979, p. 2.

- Wilson 1979, p. 17.

- Ordnance Survey 1848

- Wilson 1979, p. 11.

- Pilkington, Salford Hundred, retrieved 16 December 2008

- Wilson 1979, p. 52.

- Wilson 1979, p. 62.

- Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive (30 April 2008), Network Maps: Manchester North (PDF), gmpte.com, archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2008, retrieved 20 December 2008

- Office for National Statistics (2001), Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3 (PDF), statistics.gov.uk, retrieved 9 July 2007

- Wilson 1979, p. 61.

- Wilson 1979, p. 68.

- www.sixtownhousing.org, Six Town Housing. "About Us". Six Town Housing. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS06 Ethnic group

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 5 August 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 5 August 2008 - Bury Metropolitan Borough ethnic group, Statistics.gov.uk Retrieved on 20 December 2008.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 September 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 September 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS04 Marital status

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 31 August 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 31 August 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS20 Household composition

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 December 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 December 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS13 Qualifications and students

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 5 August 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 5 August 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS07 Religion

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 December 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 20 December 2008 - Wilson 1979, p. 3.

- Wilson 1979, p. 10.

- Wilson 1979, p. 69.

- Whitefield Urban District, Vision of Britain, archived from the original on 26 October 2012

- 1981 Key Statistics for Urban Areas GB Table 1, Office for National Statistics, 1981

- 1991 Key Statistics for Urban Areas, Office for National Statistics, 1991

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS01 Usual resident population

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 19 December 2008

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 19 December 2008 - "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS09a Economic activity – all people

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 18 April 2009

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 18 April 2009 - Bury Local Authority economic activity, Statistics.gov.uk, retrieved 18 April 2009

- Wilson 1979, p. 57.

- Wilson 1979, pp. 52–53.

- Wilson 1979, p. 53.

- Wilson 1979, p. 56.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics – Urban area results by population size of urban area", ons.gov.uk, Office for National Statistics, KS11a Industry of employment – all people

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 17 April 2009

, 22 July 2004, retrieved 17 April 2009 - Stockport Local Authority industry of employment, Statistics.gov.uk, retrieved 18 April 2009

- Wilson 1979, p. 20.

- Wilson 1979, p. 21.

- Wilson 1979, p. 48.

- Wilson 1979, p. 58.

- Wilson 1979, p. 59.

- Wells 1995, pp. 102–103.

- Marshall 1970, pp. 170–173.

- Wilson 1979, p. 60.

- Simpson 1994, p. 57.

- Marshall 1970, p. 55.

- Wilson 1979, pp. 5–8.

- Wilson 1979, pp. 10.

- Wilson 1979, p. 28.

- Wilson 1979, pp. 25–26.

- Wilson 1979, p. 25.

- Butterworth 1841, p. 114.

- Wilson 1979, p. 26.

- Conservation Areas, Bury Metropolitan Borough Council, retrieved 19 December 2008

- Wilson 1979, p. 70.

- St Bernadettes RC Church, St. Bernadette's, retrieved 20 December 2008

- Anon (27 August 2010). "Eruv is a big step nearer". Jewish Telegraph. Prestwich: Jewish Telegraph. p. 1.

- Kalmus, Jonathan (26 August 2010). "Manchester plans eruv". The Jewish Chronicle. Manchester: The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Wilson 1979, p. 24.

- Wilson 1979, pp. 54–55.

- Wilson 1979, p. 35.

- Borough of Radcliffe 1935, p. 20.

Bibliography

- Borough of Radcliffe (21 September 1935), Charter Celebrations, Bury Library Local Studies

- Butterworth, Edwin (1841), A statistical sketch of the county palatine of Lancaster, Oxford University: N/A

- Chetham Society (1861), Remains, Historical and Literary, Connected with the Palatine Counties of Lancaster and Chester, Harvard University: Chetham Society

- Coward, Barry (1983), The Stanleys, Lords Stanley, and Earls of Derby, 1385—1672, Manchester University Press ND, ISBN 0-7190-1338-0

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, John (1911), "The Parish of Prestwich with Oldham – Pilkington", A History of the County of Lancaster, Vol. 5, British History Online

- Holt, Thomas (1962), Pilkington Park: an account of Whitefield, Besses o' th' Barn, and their parish, Prestwich & Whitefield Guide

- Marshall, John (1970), The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway, Volume 2, David & Charles

- Ordnance Survey (1848), Lancashire & Furness, 1:10560, Ordnance Survey

- Simpson, Barry J. (1994), Urban Public Transport Today, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-419-18780-4

- Wells, Jeffrey (1995), An Illustrated Historical Survey of the Railways in and Around Bury, Challenger Publications, ISBN 1-899624-29-5

- Wilson, John F (1979), A History of Whitefield, John F Wilson, ISBN 0-9506795-1-8

Further reading

- McLachlan, Herbert (1950). "Stand Chapel, 1693-1943". Essays and Addresses. Manchester University Press. pp. 112–130.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whitefield, Greater Manchester. |