Belgravia

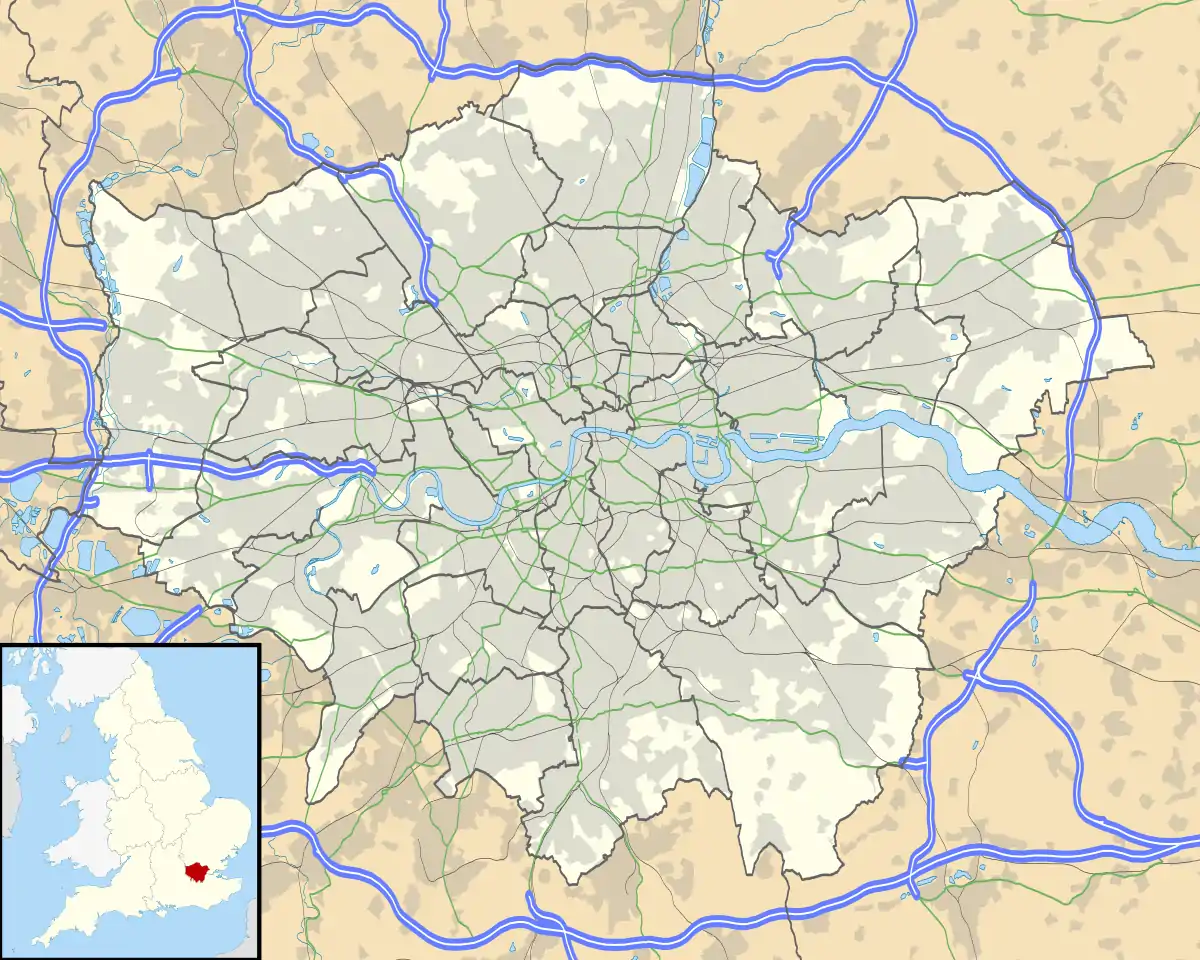

Belgravia (/bɛlˈɡreɪviə/)[1] is an affluent district in Central London,[2] covering parts of the areas of both the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

| Belgravia | |

|---|---|

Chester Square, Belgravia, in March 2009 | |

Belgravia Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ275795 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | SW1X, SW1W |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Belgravia was known as 'Five Fields' during the Middle Ages, and became a dangerous place due to highwaymen and robberies. It was developed in the early 19th century by Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster under the direction of Thomas Cubitt, focusing on numerous grand terraces centred on Belgrave Square and Eaton Square. Much of Belgravia, known as the Grosvenor Estate, is still owned by a family property company, the Duke of Westminster's Grosvenor Group, although owing to the Leasehold Reform Act 1967, the estate has been forced to sell many freeholds to its former tenants.

Name

Belgravia takes its name from one of the Duke of Westminster's subsidiary titles, Viscount Belgrave, which is in turn derived from Belgrave, Cheshire, a village on land belonging to the Duke.

Geography

Belgravia is near the former course of the River Westbourne, a tributary of the River Thames.[3] The area is mostly in the City of Westminster, with a small part of the western section in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.[4]

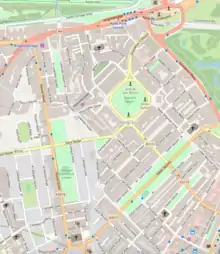

The district lies mostly to the south-west of Buckingham Palace, and is bounded notionally by Knightsbridge (the road) to the north, Grosvenor Place and Buckingham Palace Road to the east, Pimlico Road to the south,[5] and Sloane Street to the west. To the north is Hyde Park, to the northeast is Mayfair and Green Park and to the east is Westminster.[6]

The area is mostly residential, the particular exceptions being Belgrave Square in the centre, Eaton Square to the south, and Buckingham Palace Gardens to the east.[7]

The nearest London Underground stations are Hyde Park Corner, Knightsbridge and Sloane Square. Victoria station, a major National Rail, tube and coach interchange, is to the east of the district. Frequent bus services run to all areas of Central London from Grosvenor Place.[8] The A4, a major road through West London, and the London Inner Ring Road run along the boundaries of Belgravia.[6]

History

The area takes its name from the village of Belgrave, Cheshire, two miles (3 km) from the Grosvenor family's main country seat of Eaton Hall.[3] One of the Duke of Westminster's subsidiary titles is Viscount Belgrave.[9]

During the Middle Ages, the area was known as the Five Fields and was a series of fields used for grazing, intersected by footpaths.[3] The Westbourne was crossed by Bloody Bridge, so called because it was frequented by robbers and highwaymen, and it was unsafe to cross the fields at night. In 1728, a man's body was discovered by the bridge with half his face and five fingers removed. In 1749, a muffin man was robbed and left blind. Five Fields' distance from London also made it a popular spot for duelling.[10]

Despite its reputation for crime and violence, Five Fields was a pleasant area during the daytime, and various market gardens were established. The area began to be built up after George III moved to Buckingham House and constructed a row of houses on what is now Grosvenor Place. In the 1820s, Richard Grosvenor, 2nd Marquess of Westminster asked Thomas Cubitt to design an estate. Most of Belgravia was constructed over the next 30 years; it attempted to rival Mayfair in its prestige.[10]

Belgravia is characterised by grand terraces of white stucco houses, and is focused on Belgrave Square and Eaton Square. It was one of London's most fashionable residential districts from its beginnings.[11] After World War II, some of the largest houses ceased to be used as residences, or townhouses for the country gentry and aristocracy, and were increasingly occupied by embassies, charity headquarters, professional institutions and other businesses. Belgravia has become a relatively quiet district in the heart of London, contrasting with neighbouring districts, which have far more busy shops, large modern office buildings, hotels and entertainment venues. Many embassies are located in the area, especially in Belgrave Square.[3]

In the early 21st century, some houses are being reconverted to residential use, because offices in old houses are no longer as desirable as they were in the post-war decades, while the number of super-rich in London is at a high level not seen since at least 1939. The average house price in Belgravia, as of March 2010, was £6.6 million,[12] although many houses in Belgravia are among the most expensive anywhere in the world, costing up to £100 million, £4,671 per square foot (£50,000 per m2).[13]

As of 2013, many residential properties in Belgravia were owned by wealthy foreigners who may have other luxury residences in exclusive locations worldwide; so many are temporarily unoccupied because their owners are elsewhere. The increase in land value has been in sharp contrast to UK average and left the area empty and isolated.[14]

Squares and streets

Belgrave Square

Belgrave Square, one of the grandest and largest 19th-century squares, is the centrepiece of Belgravia. It was laid out by the property contractor Thomas Cubitt for the 2nd Earl Grosvenor, later to be the 1st Marquess of Westminster, beginning in 1826. Building was largely complete by the 1840s.[15]

The original scheme consisted of four terraces, each made up of eleven grand white stuccoed houses, apart from the south-east terrace, which had twelve; detached mansions were in three of the corners and there was a private central garden.[3] The numbering is anti-clockwise from the north: NW terrace Nos. 1 to 11, west corner mansion No. 12, SW terrace 13–23, south corner mansion No. 24, SE terrace Nos. 25–36, east corner mansion No. 37, NE terrace Nos. 38–48.[16]

There is also a slightly later detached house at the northern corner, No. 49, which was built by Cubitt for Sidney Herbert in 1847.[3] The terraces were designed by George Basevi (cousin of Benjamin Disraeli). The largest of the corner mansions, Seaford House in the east corner, was designed by Philip Hardwick, and the one in the west corner was designed by Robert Smirke, completed around 1830.[3]

The square contains statues of Christopher Columbus, Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, Prince Henry the Navigator, the 1st Marquess of Westminster, a bust of George Basevi and a sculpture entitled "Homage to Leonardo, the Vitruvian Man", by Italian sculptor Enzo Plazzotta.[17]

Eaton Square

Eaton Square is one of three garden squares built by the Grosvenor family, and is named after Eaton Hall, Cheshire, the family's principal seat. It is longer but less grand than Belgrave Square, and is an elongated rectangle. The first block was laid out by Cubitt in 1826, but the square was not completed until 1855, the year of his death. The long construction period is reflected in the variety of architecture along the square.[18]

The houses in Eaton Square are large, predominantly three bay wide buildings, joined in regular terraces in a classical style, with four or five main storeys, plus attic and basement and a mews house behind. The square is one of London's largest and is divided into six compartments by the upper end of Kings Road (northeast of Sloane Square), a main road, now busy with traffic, that occupies its long axis, and two smaller cross streets.[19]

Although not as fashionable as some of the other squares in London, Eaton Square was home to several key figures. George FitzClarence, 1st Earl of Munster, the illegitimate son of William IV, lived at No. 13, while Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain lived at No 93 and No. 37 respectively. Since World War II, Eaton Square has become less residential; the Bolivian Embassy is at No. 106 while the Belgian Embassy is at No. 103.[18]

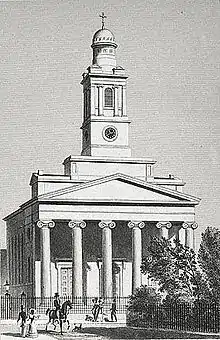

At the east end of the square is St Peter's Church. It was designed by Henry Hakewill and built between 1824 and 1827 during the first development of Eaton Square. The first church was destroyed by fire in 1836 and rebuilt by Hakewill, and again in 1987, when it was restored by the Braithwaite Partnership.[19][20] It is a Grade II* listed building, in a Greek revival style featuring a six-columned Ionic portico and a clock tower.[21][20]

Eaton Place is an extension to the square, developed by Cubitt between 1826 and 1845. The scientist William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin lived here, as did the Irish Unionist Edward Carson. Sir Henry Wilson, 1st Baronet was assassinated by Irish Republicans in 1922 as he was leaving No. 36.[18]

Upper Belgrave Street

Upper Belgrave Street was constructed in the 1840s to connect King's Road with Belgrave Square.[22] It is a wide one-way residential street with grand white stuccoed buildings. It stretches from the south-east corner of Belgrave Square to the north-east corner of Eaton Square. Most of the houses have now been divided into flats and achieve sale prices as high as £3,500 per square foot. Many of the buildings were constructed by Cubitt in the 1820s and 1830s.

Walter Bagehot, a writer, banker and economist, lived at No. 12 during the 1860s. Alfred, Lord Tennyson lived at No 9 in 1880–1881. John Bingham, 7th Earl of Lucan lived at No. 46, and disappeared without trace from there in 1974 after his children's nanny was found murdered.[22]

Chester Square

Chester Square is a smaller, residential garden square, the last of the three garden squares built by the Grosvenor family. It is named after the city of Chester, near Eaton Hall. Members of the family also represented Chester as Members of Parliament.[23] The garden, just under 1.5 acres (6,100 m2) in size, is planted with shrubs and herbaceous borders. It was refurbished in 1997, to the layout that appears in the Ordnance Survey map of 1867. Past residents include the poet Matthew Arnold (1822–88) at No. 2, Mary Shelley (1797–1851) at No. 24, John Liddell (1794–1868) at No. 72, Margaret Thatcher (1925–2013) at No. 73, and Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands (1880–1962) resided at No. 77 from 1940 until 1945.[24][25]

Wilton Crescent

Wilton Crescent was created by Thomas Cundy II, the Grosvenor family estate surveyor, and was drawn up with the original 1821 Wyatt plan for Belgravia.[26] It is named after the 2nd Earl of Wilton, second son of the 1st Marquess of Westminster. The street was built in 1827 by William Howard Seth-Smith.[27]

In the 19th and 20th centuries, it was home to many prominent British politicians, ambassadors and civil servants. Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma lived at No. 2 for many years and Alfonso López Pumarejo, twice President of Colombia, lived and died at No. 33 (which is marked by a blue plaque).[27][28]

Like much of Belgravia, Wilton Crescent has grand terraces with lavish white houses which are built in a crescent shape, many of them with stuccoed balconies, particularly in the southern part of the crescent. The houses to the north of the crescent are stone clad, and five storeys high, and were refaced between 1908 and 1912. Most of the houses had originally been built in the stucco style, but such houses became stone clad during this renovation period. Other houses today have black iron balconies.

Wilton Crescent lies east of Lowndes Square and Lowndes Street, to the northwest of Belgrave Square. It is accessed via Wilton Place, constructed in 1825 to connect it to Knightsbridge.[27] It is adjacent to Grosvenor Crescent to the east, which contains the Indonesian Embassy. Further to the east lies Buckingham Palace. The play Major Barbara is partly set at Lady Britomart's house in Wilton Crescent. In 2007, Wilton Garden, in the middle of the crescent, was awarded a bronze medal by the London Gardens Society.

Lowndes Square

Lowndes Square is named after the Secretary to the Treasury William Lowndes.[29] Like much of Belgravia, it has grand terraces with white stucco houses. To the east lie Wilton Crescent and Belgrave Square. The square runs parallel with Sloane Street to the east, east of the Harvey Nichols department store and Knightsbridge Underground station. It has some of the most expensive properties in the world. Russian businessman Roman Abramovich bought two stucco houses in Lowndes Square in 2008. The merged houses, with a total of eight bedrooms, are expected to be worth £150 million, which exceeds the value of the previous most expensive house in London.[30]

George Basevi designed many of the houses in the square. Mick Jagger and James Fox once filmed in Leonard Plugge's house in Lowndes Square. The square was used as a setting for the Edward Frederic Benson novel The Countess of Lowndes Square.[31]

Cultural references

The novels of Anthony Trollope (1815–1882): The Way We Live Now, Phineas Finn, Phineas Redux, The Prime Minister, and The Duke's Children all give accurate descriptions of 19th-century Belgravia.

In Brideshead Revisited, a novel by Evelyn Waugh, Belgravia's Pont Street is eponymous with the idiosyncrasies of the British upper classes. Julia, one of the main protagonists, tells her friends, "It was Pont Street to wear a signet ring and to give chocolates at the theatre; it was Pont Street to say, 'Can I forage for you?' at a dance."

Flunkeyania or Belgravian Morals, written under the pseudonym "Chawles", was one of the novels serialised in The Pearl, an allegedly pornographic Victorian magazine.[32]

In the popular British television series Upstairs, Downstairs (1971–1975), the scene is set in the household of Richard Bellamy (later 1st Viscount Bellamy of Haversham) at 165 Eaton Place, Belgravia (65 Eaton Place was used for exterior shots; a "1" was painted in front of the house number).[33] It depicts the lives of the Bellamys and their staff of domestic servants in the years 1903–1930, as they experience the tumultuous events of the Edwardian era, World War I and the postwar 1920s, culminating with the stock market crash of 1929, which ends the world they had known. In 2010, filming began on a mini-series intended to pick up the story of one of the main characters, Rose Buck, in 1936, as she returns to 165 Eaton Place to serve as the Holland family's housekeeper.

In Downton Abbey Lady Rosamund Painswick, sister of Lord Grantham, lives in Belgrave Square.[34]

The first episode of the second series of the television programme Sherlock is "A Scandal in Belgravia", loosely based on the Arthur Conan Doyle short story "A Scandal in Bohemia".[35]

Belgravia is a period television series, broadcast in 2020, based on a novel of the same name by Julian Fellowes, published in 2016, which Fellowes adapted himself for the series.

At Netflix 's 'royal' Christmas movie universe (including to 2020 the movies A Christmas Prince 1-2-3, The Princess Switch 1-2, and A Royal Winter) Belgravia is one of fictitious European monarchies among Aldovia, Penglia and Montenaro, where these stories takes place. According to a fictional map, visible at A Christmas Prince 3, fictional country of Belgravia is about in place of Hungary, Ukraine, and Romania.

References

Citations

- "Belgravia". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- "London's Places" (PDF). The London Plan. Greater London Authority. 2011. p. 46. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 56.

- Westminster City Council (Map). Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Belgravia – "The rich man's Pimlico"". City West Homes Residential. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- "Belgravia, London". Google Maps. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 57, 263.

- Transport to and from Belgravia tfl.gov.uk

- "Chester Palatinate – Richard Grosvenor (Viscount Belgrave)". The National Archives. 1829. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 57.

- Fodor's London 2014. Fodor's Travel. 2013. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-770-43220-1.

- "Belgravia square tops expensive homes list". BBC News. 8 March 2010. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Record £100m price-tag on London house". London Evening Standard. 14 April 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Sarah Lyall (1 April 2013). "A Slice of London So Exclusive Even the Owners Are Visitors". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, pp. 56–57.

- "Belgrave Square, Belgravia, London". Google Maps. Zoom around the Streetview plan to verify house numbers. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Bob Speel. "Belgrave Square". Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 263.

- Brandon & Brooke 2016, p. 26.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 813.

- Historic England. "Church of St Peter (Grade II*) (1356980)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 961.

- Walford, Edward (1878). 'The western suburbs: Belgravia', Old and New London. pp. 1–14. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- Steves, Rick. (2012). Rick Steves' England 2013. Avalon Travel Publishing. p. 168. ISBN 1612383890.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 161.

- "Opensquares.org". Opensquares.org. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 1025.

- "Alfonso Lopez-Pumarejo blue plaque in London". Blue Plaques. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 517.

- "London's 'Chester Square' tops list of Britain's priciest addresses". The Daily Telegraph. 8 March 2010. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "The Countess of Lowndes square, and the stories : Benson, E. F. (Edward Frederic), 1867–1940 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Chawles, [pseud.]. "Biblio book sales". Biblio.com. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- "Upstairs, Downstairs The house 1". Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- Pattison, Cindy (9 October 2016). "Downton Abbey £62m mansion caught in billionaire crossfire". The Daily Star. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Crompton, Sarah (1 January 2012). "The timeless appeal of Holmes's sexy logic". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

Sources

- Brandon, David; Brooke, Alan (2016). Secrets of Central London's Squares. Amberley. ISBN 978-1-445-65665-6.

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (2nd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belgravia. |

- Map of Belgravia and surrounding areas

- The Belgravia Society – Largest local civic amenity body