List of chemical element name etymologies

This article lists the etymology of chemical elements of the periodic table.

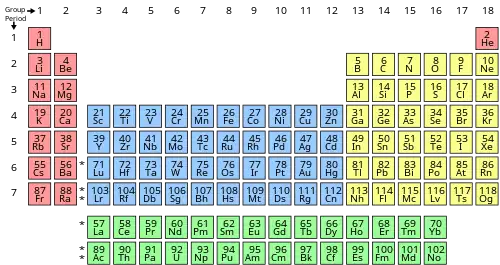

| Part of a series on the |

| Periodic table |

|---|

|

History

Throughout the history of chemistry, several chemical elements have been discovered. In the nineteenth century, Dmitri Mendeleev formulated the periodic table, a table of elements which describes their structure. Because elements have been discovered at various times and places, from antiquity through the present day, their names have derived from several languages and cultures.

Table

| Element | Language of origin | Original word | Meaning | Symbol origin | Description | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hydrogen | H | Greek via Latin and French | ὕδωρ (root: ὑδρ-) + -γενής (-genes) | water + begetter | descriptive | From French hydrogène[1] and Latin hydro- and -genes, derived from the Greek ὕδωρ γείνομαι (hydor geinomai), meaning "Ι beget water". | ||||

| 2 | Helium | He | Greek | ἥλιος (hélios) | sun | astrological; mythological | Named after the Greek ἥλιος (helios), which means "the sun" or the mythological sun-god.[2] It was first identified by its characteristic emission lines in the Sun's spectrum. | ||||

| 3 | Lithium | Li | Greek | λίθος (lithos) | stone | From Greek λίθος (lithos) "stone", because it was discovered from a mineral while other common alkali metals (sodium and potassium) were discovered from plant tissue. | |||||

| 4 | Beryllium | Be | Sanskrit, Pali, and Prakrit via Greek, Latin, Old French, and Middle English | City of Belur via Greek βήρυλλος (beryllos) | a blue-green spar (beryllium aluminium cyclosilicate, Be3Al2(SiO3)6). Possibly related to the name of Belur. | descriptive (colour): beryl | βήρυλλος beryllos, denoting beryl, which contains beryllium.[3] The word is derived (via Latin: beryllus and French: béryl) from the Greek βήρυλλος, bērullos, a blue-green spar, from Prakrit veruliya (वॆरुलिय), from Pāli veḷuriya (वेलुरिय); veḷiru (भेलिरु) or, viḷar (भिलर्), "to become pale," in reference to the pale semiprecious gemstone beryl.[4] The word is ultimately derived from the Sanskrit word वैडूर्य vaidurya, which might be related to the name of the Indian city of Belur.[5] | ||||

| 5 | Boron | B | Arabic, Medieval Latin, Anglo-Norman, Middle French, and Middle English | بورق (buraq) | Latin borax from Arabic | From the Arabic بورق (buraq), which refers to borax. Possibly derived from the Persian, بوره (burah). The Arabic was adapted as Medieval Latin baurach, Anglo-Norman boreis, and Middle English boras, which became the source of the English "boron". | |||||

| 6 | Carbon | C | Latin via French | charbone | charcoal | Latin carbo | From the French, charbone, which in turn came from Latin carbō, which means "charcoal" and is related to carbōn, which means "a coal". (The German and Dutch names, "Kohlenstoff" and "koolstof", respectively, both literally mean "coal matter".) These words were derived from the PIE base *ker- meaning heat, fire, or to burn.[6] | ||||

| 7 | Nitrogen | N | Greek via Latin and French | νίτρον (Latin: nitrum) -γενής (-genes) | native-soda begetter | descriptive | From French "nitrogène",[7] derived from Greek νίτρον γείνομαι (nitron geinomai), meaning "I form/beget native-soda (niter)".[8] Also used was azoth, from Andalusian Arabic al-zuq, from the Classical Arabic name of the element. | ||||

| 8 | Oxygen | O | Greek via French | ὀξύ γείνομαι (oxy geinomai)/oxygène | to bring forth acid | From Greek ὀξύ γείνομαι (oxy geinomai), which means "Ι bring forth acid", as it was believed to be an essential component of acids. This phrase was corrupted into the French oxygène, which became the source of the English "oxygen".[9] | |||||

| 9 | Fluorine | F | Latin | fluor | a flowing | From fluorspar, one of its compounds (calcium fluoride, CaF2). | |||||

| 10 | Neon | Ne | Greek | νέος (neos) | new | From Greek "νέος" (neos), which means "new". | |||||

| 11 | Sodium | Na | English | soda | From the English "soda", used in names for sodium compounds such as caustic soda, soda ash, and baking soda. Probably from Italian sida (or directly from Medieval Latin soda) "a kind of saltwort," from which soda was obtained, of uncertain origin.[10]

| ||||||

| 12 | Magnesium | Mg | Greek | Μαγνησία (Magnesia) | toponym | From the Ancient Greek Μαγνησία (Magnesia) (district in Thessaly), where discovered. | |||||

| 13 | Aluminium | Al | Latin | alumen | alum (literally: bitter salt)[13] | Latin alumen | Latin alumen, which means "alum" (literally "bitter salt"). | ||||

| 14 | Silicon | Si | Latin | silex, -icis | flint | descriptive | From Latin "silex" or "silicis", which means "flint", a kind of stone (chiefly silicon dioxide). | ||||

| 15 | Phosphorus | P | Greek via Latin[14] | φῶς + -φόρος (phos + -phoros) | light-bearer | descriptive | From Greek φῶς + -φόρος (phos + phoros), which means "light bearer", because white phosphorus emits a faint glow upon exposure to oxygen. Phosphorus was the ancient name for Venus, or Hesperus, the (Morning Star).[2] | ||||

| 16 | Sulfur | S | Latin Proto-Indo-European | Old Latin sulpur (later sulphur, sulfur) PIE *swépl̥ (genitive *sulplós), nominal derivative of *swelp.[15] | > PIE *swelp 'to burn' | Latin sulfur | The word came into Middle English from Anglo-Norman sulfre, itself derived through Old French soulfre from Late Latin sulfur.[16] | ||||

| 17 | Chlorine | Cl | Greek | χλωρός (chlorós) | pale green[17] | descriptive (colour): Greek chloros | From Greek χλωρός (chlorós), which means "yellowish green" or "greenish yellow", because of the colour of the gas. | ||||

| 18 | Argon | Ar | Greek | ἀργόν (argon) | inactive | descriptive: argon | Greek argon means "inactive" (literally "slow"). | ||||

| 19 | Potassium | K | Modern Latin via Dutch and English[18] | potassa; potasch via potash[19] | pot-ash | From the English "potash", which means "pot-ash" (potassium compound prepared from an alkali extracted in a pot from the ash of burnt wood or tree leaves). Potash is a literal translation of the Dutch potaschen, which means "pot ashes".[18] The symbol K is from the Latin name kalium, from Arabic القلي (al qalīy), which means "calcined ashes". | |||||

| 20 | Calcium | Ca | Greek/Latin | χάλιξ/calx | χάλιξ means "pebble", and calx means limestone[20] | Latin calx | From Latin calx, which means "lime". Calcium was known as early as the first century when the Ancient Romans prepared lime as calcium oxide. | ||||

| 21 | Scandium | Sc | Latin | Scandia | Scandinavia | toponym | Named from Latin Scandia, which means Scandinavia; formerly eka-boron.[21] | ||||

| 22 | Titanium | Ti | Greek | Τιτάν Titan (gen.: Τιτάνος) | Titans, sons of Gaia | mythological | For the "Titans", the first sons of Gaia in Greek mythology.[2] | ||||

| 23 | Vanadium | V | Old Norse | Vanadís | "Dís of the Vanir" | mythological | From Vanadís, one of the names of the Vanr goddess Freyja in Norse mythology, because of multicoloured chemical compounds deemed beautiful.[2][22] | ||||

| 24 | Chromium | Cr | Greek via French | χρῶμα (chróma) | colour | descriptive (colour): Greek chroma | From Greek χρῶμα (chróma), "colour", because of its multicoloured compounds. This word was adapted as the French chrome, and adding the suffix -ium created the English "chromium".[23] | ||||

| 25 | Manganese | Mn | Greek via Latin, Italian, and French | Μαγνησία (Magnesia; Medieval Latin: magnesia) |

Magnesia | descriptive | From Latin Magnesia, ultimately from Greek; Magnesia evolved into "manganese" in Italian and into "manganèse" in French. | ||||

| 26 | Iron | Fe | Anglo-Saxon via Middle English | īsern (earlier: īren/īsen) /yren/yron | holy metal or strong metal[24] | descriptive: Anglo-Saxon | From the Anglo-Saxon īsern which is derived from Proto-Germanic isarnan meaning "holy metal" or "strong metal". The symbol Fe is from Latin ferrum, meaning "iron". | ||||

| 27 | Cobalt | Co | German | Kobold | goblin | German kobold | From German Kobold, which means "goblin". The metal was named by miners, because it was poisonous and troublesome (polluted and degraded other mined elements, such as nickel). Other sources cite the origin in the silver miners' belief that cobalt had been placed by "Kobolds", who had stolen the silver. Some also think that the name may have been derived from Greek κόβαλος, kobalos, which means "mine" and which may have common roots with kobold, goblin, and cobalt. | ||||

| 28 | Nickel | Ni | Swedish via German[25] | Kopparnickel/ Kupfernickel | copper-coloured ore | descriptive | From the Swedish kopparnickel, meaning "copper-coloured ore"; this referred to the ore niccolite from which it was obtained.[25] | ||||

| 29 | Copper | Cu | Greek? via Latin, West Germanic, Old English, and Middle English[26] | Κύπριος (Kyprios)? | who/which is from Cyprus | toponym: Latin Cuprum | Possibly derived from Greek Κύπριος (Kyprios) (which comes from Κύπρος (Kypros), the Greek name of Cyprus) via Latin cuprum, West Germanic *kupar, Old English coper/copor, and Middle English coper. The Latin term, during the Roman Empire, was aes cyprium; "aes" was the generic term for copper alloys such as bronze). Cyprium means "Cyprus" or "which is from Cyprus", where so much of it was mined; it was simplified to cuprum and then eventually Anglicized as copper (Old English coper/copor). | ||||

| 30 | Zinc | Zn | German | Zink | Cornet | From German Zink which is related to Zinken "prong, point", probably alluding to its spiky crystals. May be derived from Old Persian. | |||||

| 31 | Gallium | Ga | Latin | Gallia | Gaul (Ancient France) | toponym | From Latin Gallia, which means Gaul (Ancient France), and also gallus, which means "rooster". The element was obtained as free metal by Lecoq de Boisbaudran, who named gallium after France, his native land, and also, punningly, after himself, as Lecoq, which means "the rooster", or in Latin, gallus.

Gallium was called eka-aluminium by Mendeleev who predicted its existence.[21] | ||||

| 32 | Germanium | Ge | Latin | Germania | Germany | toponym | From Latin Germania, which means "Germany". Germanium has also been called eka-silicon by Mendeleev.[21] | ||||

| 33 | Arsenic | As | Syriac/Persian via Greek, Latin, Old French, and Middle English | ἀρσενικόν (arsenikon) | orpiment | Greek arsenikon | From Greek ἀρσενικόν (arsenikon), which is adapted from the Syriac ܠܐ ܙܐܦܢܝܐ (al) zarniqa[27] and Persian, زرنيخ (zarnik), "yellow orpiment". Ἀρσενικόν (arsenikon) is paretymologically related to the Greek word ἀρσενικός (arsenikos), which means "masculine" or "potent". These words were adapted as the Latin arsenicum and Old French arsenic, which is the source for the English arsenic.[27] | ||||

| 34 | Selenium | Se | Greek | σελήνη (selene) | moon | astrological; mythological | From Greek σελήνη (selene), which means "Moon", and also moon-goddess Selene.[2] | ||||

| 35 | Bromine | Br | Greek via French | βρόμος (brómos)[28] | dirt or stench (of he-goats)[29] | Greek bromos | βρόμος (brómos) means "stench (lit. clangor)", due to its characteristic smell. | ||||

| 36 | Krypton | Kr | Greek | κρυπτός (kryptos) | hidden | descriptive | From Greek κρυπτός (kryptos), which means "hidden one", because of its colourless, odorless, tasteless, gaseous properties, as well as its rarity in nature. | ||||

| 37 | Rubidium | Rb | Latin | rubidus | deepest red | descriptive (colour) | From Latin rubidus, which means "deepest red", because of the colour of a spectral line. | ||||

| 38 | Strontium | Sr | Scottish Gaelic via English | Sròn an t-Sìthein; Strontian | proper name (literally: "nose [i.e., 'point'] of the fairy hill)" | toponym | Named after strontianite, the mineral. (Strontianite was named after the town of Strontian, the source of the mineral in Scotland.) | ||||

| 39 | Yttrium | Y | Swedish | Ytterby | proper name, literally: "outer village" | toponym | Named after yttria, the (oxide) compound of yttrium. (The compound yttria was named after Ytterby, the village where the mineral gadolinite was also found.) | ||||

| 40 | Zirconium | Zr | Syriac/Persian via Arabic and German | ܙܐܪܓܥܢܥ zargono,[30] زرگون (zargûn) | gold-like | From Arabic زركون (zarkûn). Derived from the Persian, زرگون (zargûn), which means "gold-like". Zirkon is the German variant of these and is the origin of the English "zircon".[31] | |||||

| 41 | Niobium | Nb | Greek | Νιόβη (Niobe) | snowy | mythological | Named after Niobe, daughter of Tantalus in Classical mythology.[22][2] The alternate name columbium comes from Columbia, personification of America. | ||||

| 42 | Molybdenum | Mo | Greek | μόλυβδος (molybdos) | lead-like | descriptive | From Greek μόλυβδος (molybdos), "lead". | ||||

| 43 | Technetium | Tc | Greek | τεχνητός (technetos) | artificial | descriptive | From Greek τεχνητός (technetos), which means "artificial", because it was the first artificially produced element. Technetium has also been called eka-manganese.[21] | ||||

| 44 | Ruthenium | Ru | Latin | Ruthenia | Ruthenia, Kievan Rus' [32] | toponym | From Latin Ruthenia, geographical exonym for Kievan Rus'. | ||||

| 45 | Rhodium | Rh | Greek | ῥόδον (rhodon) | rose | descriptive (colour) | From Greek ῥόδον (rhodon), which means "rose". From rose-red compounds. | ||||

| 46 | Palladium | Pd | Greek via Latin | Παλλάς (genitive: Παλλάδος) (Pallas) | little maiden[33] | astrological; mythological | Named after Pallas, the asteroid discovered two years earlier. (The asteroid was named after Pallas Athena, goddess of wisdom and victory.)[2] The word Palladium is derived from Greek Παλλάδιον and is the neuter version of Παλλάδιος, meaning "of Pallas".[34] | ||||

| 47 | Silver | Ag | Akkadian via Anglo-Saxon and Middle English | 𒊭𒁺𒁍/𒊭𒅈𒇥; siolfor/seolfor | to refine, smelt | Latin argentum | From the Anglo-Saxon, seolfor which was derived from Proto-Germanic *silubra-; compare Old High German silabar; and has cognates in Balto-Slavic languages: Church Slavonic: sĭrebro, Lithuanian: sidabras, Old Prussian sirablan. Possibly borrowed from Akkadian 𒊭𒅈𒇥 sarpu "refined silver" and related to 𒊭𒁺𒁍 sarapu "to refine, smelt".[35] Alternatively, possibly from one of the Pre-Indo-European languages, compare Basque: zilar. The symbol Ag is from the Latin name argentum, which is derived from PIE *arg-ent-. | ||||

| 48 | Cadmium | Cd | Greek/Latin | καδμεία (kadmeia) | calamine or Cadmean earth | Greek kadmia | From Latin cadmia, which is derived from Greek καδμεία (kadmeia) and means "calamine", a cadmium-bearing mixture of minerals. Cadmium is named after Cadmus (in Greek: Κάδμος Kadmos), a character in Greek mythology and calamine is derived from Le Calamine, the French name of the Belgian town of Kelmis. | ||||

| 49 | Indium | In | Greek via Latin and English | indigo | descriptive (colour) | Named after indigo, because of an indigo-coloured spectrum line. The English word indigo is from Spanish indico and Dutch indigo (from Portuguese endego), from Latin indicum "indigo," from Greek ἰνδικόν, indikon, "blue dye from India". | |||||

| 50 | Tin | Sn | Anglo-Saxon via Middle English | tin | Borrowed from a Proto-Indo-European language, and has cognates in several Germanic and Celtic languages.[36] The symbol Sn is from its Latin name stannum. | ||||||

| 51 | Antimony | Sb | Greek? via Medieval Latin and Middle English[37] | ἀντί + μόνος (anti monos); antimonium/ antimonie[38] | various | Possibly from Greek ἀντί + μόνος (anti monos), approximately meaning "opposed to solitude", as believed never to exist in pure form, or ἀντί + μοναχός (anti monachos) for "monk-killer" (in French folk etymology, anti-moine "monk's bane"), because many early alchemists were monks, and antimony is poisonous. This may also be derived from the Pharaonic (ancient Egyptian), Antos Ammon (expression), which could be translated as "bloom of the god Ammo". The symbol Sb is from Latin name stibium, which is derived from Greek Στίβι stíbi, a variant of στίμμι stimmi (genitive: στίμμεος or στίμμιδος), probably a loan word from Arabic or Egyptian | |||||

| 52 | Tellurium | Te | Latin | Tellus | Earth | From Latin tellus ("Earth"). | |||||

| 53 | Iodine | I | Greek via French | ἰώδης (iodes) | violet | descriptive (colour) | Named after the Greek ἰώδης (iodes), which means "violet", because of the colour of the gaseous phase. This word was adapted as the French iode, which is the source of the English "iodine".[41] | ||||

| 54 | Xenon | Xe | Greek | ξένος (xenos) | foreign | From the Greek adjective ξένος (xenos), which means "foreign, a stranger". | |||||

| 55 | Caesium | Cs | Latin | caesius | blue-gray[42] or sky blue | descriptive (colour): Latin caesius | From Latin caesius, which means "sky blue". Its identification was based upon the bright-blue lines in its spectrum, and it was the first element discovered by spectrum analysis. | ||||

| 56 | Barium | Ba | Greek via Modern Latin | βαρύς (barys) | heavy | Greek barys | βαρύς (barys) means "heavy". The oxide was initially called "barote", then "baryta", which was modified to "barium" to describe the metal. Sir Humphry Davy gave the element this name because it was originally found in baryte, which shares the same source.[43] | ||||

| 57 | Lanthanum | La | Greek | λανθάνειν (lanthanein) | to lie hidden | From Greek lanthanein, "to lie (hidden)". | |||||

| 58 | Cerium | Ce | Latin | Ceres | grain, bread | astrological; mythological Ceres | Named after the asteroid Ceres, discovered two years earlier. (The asteroid, now classified as a dwarf planet, was named after Ceres, the goddess of fertility in Roman mythology.)[2] Ceres is derived from PIE *ker-es- from base *ker- meaning to grow.[44][45] | ||||

| 59 | Praseodymium | Pr | Greek | πράσιος δίδυμος (prasios didymos) | green twin | descriptive | From Greek πράσιος δίδυμος (prasios didymos), meaning "green twin", because didymium separated into praseodymium and neodymium, with salts of different colours; praseodymium oxide is green. | ||||

| 60 | Neodymium | Nd | Greek | νέος δίδυμος (neos didymos) | new twin | descriptive | Derived from Greek νέος διδύμος (neos didymos), which means "new twin", because didymium separated into praseodymium and neodymium. The metals have different-coloured salts, which helps distinguish them.[46] | ||||

| 61 | Promethium | Pm | Greek | Προμηθεύς (Prometheus) | forethought[47] | mythological | Named after Prometheus, who stole the fire of heaven and gave it to mankind (in Classical mythology).[2] | ||||

| 62 | Samarium | Sm | Samarsky-Bykhovets, Vasili | eponym | Named after samarskite, the mineral. (Samarskite was named after Colonel Vasili Samarsky-Bykhovets, a Russian mine official.) | ||||||

| 63 | Europium | Eu | Ancient Greek | Εὐρώπη (Europe) | broad-faced or well-watered | toponym; mythological | Named for Europe, where it was discovered. Europe was named after the fictional Phoenician princess Europa. | ||||

| 64 | Gadolinium | Gd | Hebrew | Gadolin, Johan | Hebrew surname; from root gadol, "great"[48] | eponym | Named in honour of Johan Gadolin, who was one of the founders of Nordic chemistry research, discovered yttrium, and pioneered laboratory exercise teaching. (Gadolinite, the mineral, is also named for him.) | ||||

| 65 | Terbium | Tb | Swedish | Ytterby | Proper name (literally: outer village) | toponym | Named after Ytterby, the village in Sweden where the element was first discovered. | ||||

| 66 | Dysprosium | Dy | Greek | δυσπρόσιτος (dysprositos) | hard to get at | descriptive | Derived from Greek δυσπρόσιτος (dysprositos), which means "hard to get at". | ||||

| 67 | Holmium | Ho | Latin | Holmia | Stockholm | toponym | Derived from Latin Holmia, which means Stockholm. | ||||

| 68 | Erbium | Er | Swedish | Ytterby | proper name, literally: "outer village" | toponym | Named after the village of Ytterby in Sweden, where large concentrations of yttria and erbia are located. Erbia and terbia were confused at this time. After 1860, what had been known as terbia was renamed erbia, and after 1877, what had been known as erbia was renamed terbia. | ||||

| 69 | Thulium | Tm | Greek | Θούλη, Θύλη[49] | a mythical country | mythological | Named after Thule, an ancient Roman and Greek name (Θούλη, Θύλη) for a mythical country in the far north, perhaps Scandinavia. By the same token, thulia, its oxide. | ||||

| 70 | Ytterbium | Yb | Swedish | Ytterby | proper name, literally: "outer village" | toponym | Named after ytterbia, the (oxide) compound of ytterbium. (The compound ytterbia was named after Ytterby, the Swedish village (near Vaxholm) where the mineral gadolinite was also found.)[22] | ||||

| 71 | Lutetium | Lu | Latin | Lutetia | Paris | toponym | Named after the Latin Lutetia (Gaulish for "place of mud"), the city of Paris.[22] | ||||

| 72 | Hafnium | Hf | Latin | Hafnia | Copenhagen | toponym | From Latin Hafnia, which means "Copenhagen" of Denmark. | ||||

| 73 | Tantalum | Ta | Greek | Τάνταλος (Tantalus) | Tantalus; possibly "the bearer" or "the sufferer"[50] | mythological | Named after the Greek Τάνταλος ("Tantalus"), who was punished after death by being condemned to stand knee-deep in water. If he bent to drink the water, it drained below the level he could reach (in Greek mythology). This was considered similar to tantalum's general non-reactivity (that is, "unreachability") because of its inertness (it sits among reagents and is unaffected by them).[2] | ||||

| 74 | Tungsten | W | Swedish and Danish | tung sten | heavy stone | descriptive | From the Swedish and Danish "tung sten", which means "heavy stone". The symbol W is from the German name Wolfram, the historical spelling Wolfrahm translates literally to "wulf cream". The names wolfram or volfram are still used in Swedish and several other languages. [22] | ||||

| 75 | Rhenium | Re | Latin | Rhenus | Rhine | toponym | From Latin Rhenus, the river Rhine. | ||||

| 76 | Osmium | Os | Greek via Modern Latin | ὀσμή (osme) | a smell | descriptive | From Greek ὀσμή (osme), meaning "a smell"; the tetroxide is foul-smelling. | ||||

| 77 | Iridium | Ir | Greek via Latin | ἴρις (genitive: ἴριδος) | of rainbows | descriptive (colour) | Named after the Latin noun iris, which means "rainbow, iris plant, iris of the eye", because many of its salts are strongly coloured; Iris was originally the name of the goddess of rainbows and a messenger in Greek mythology.[2] | ||||

| 78 | Platinum | Pt | Spanish via Modern Latin | platina (del Pinto) | little silver (of the Pinto River)[51] | descriptive | From the Spanish, platina, which means "little silver", because it was first encountered in a silver mine. Platina can also mean "stage (of a microscope)", and the modern Spanish is platino. Platina is a diminutive of plata (silver); it is a loan word from French plate or Provençal plata (sheet of metal) and is the origin of the English "plate".[52] | ||||

| 79 | Gold | Au | Anglo-Saxon via Middle English | gold | descriptive (colour): Latin aurum | From the Anglo-Saxon, "gold", from PIE *ghel- meaning "yellow/ bright". Au is from Latin aurum, which means "shining dawn".[53] | |||||

| 80 | Mercury | Hg | Latin | Mercurius | Mercury | mythological | Named after Mercury, the god of speed and messenger of the Gods, as was the planet Mercury named after the god. The symbol Hg is from the Greek words ὕδωρ and ἀργυρός (hydor and argyros), which became the Latin hydrargyrum; both mean "water-silver", because it is a liquid like water (at room temperature), and has a silvery metallic sheen.[2][54] | ||||

| 81 | Thallium | Tl | Greek | θαλλός (thallos) | green twig | descriptive | From Greek θαλλός (thallos), which means "a green shoot (twig)", because of its bright-green spectral emission lines. | ||||

| 82 | Lead | Pb | Anglo-Saxon | lead | The symbol Pb is from the Latin name plumbum, hence the English "plumbing".[2][55] | ||||||

| 83 | Bismuth | Bi | Modern Latin from German | bisemutum | white mass | descriptive (colour): bisemutum | bisemutum is derived from German Wismuth, perhaps from weiße Masse, and means "white mass", due to its appearance. | ||||

| 84 | Polonium | Po | Latin | Polonia | Poland | toponym | Named after Poland, homeland of discoverer Marie Curie. Was also called radium F. | ||||

| 85 | Astatine | At | Greek | ἄστατος (astatos) | unstable | Greek astatos | ἄστατος (astatos) means "unstable".[56] | ||||

| 86 | Radon | Rn | Latin via German and English[57] | Radium | Contraction of radium emanation, since the element appears in the radioactive decay of radium. An alternative, rejected name was niton (Nt), from Latin nitens "shining", because of the radioluminescence of radon. | ||||||

| 87 | Francium | Fr | French | France | proper name (Land of the Franks) | toponym | Named for France, where it was discovered (at the Curie Institute (Paris)). | ||||

| 88 | Radium | Ra | Latin via French | radius | ray | descriptive | From Latin radius meaning "ray", because of its radioactivity. | ||||

| 89 | Actinium | Ac | Greek | ἀκτίς (aktis) | beam | Greek aktinos | ἀκτίς, ἀκτῖνος (aktis; aktinos), which means "beam (ray)". | ||||

| 90 | Thorium | Th | Old Norse | Þōrr (modern English Thor) | thunder | mythological | Named after Thor, a god associated with thunder in Norse mythology.[2] The former name ionium (Io) was given early in the study of radioactive elements to the 230Th isotope. | ||||

| 91 | Protactinium | Pa | Greek | πρῶτος + ἀκτίς | first beam element | descriptive? | Derived from former name protoactinium, from the Greek prefix proto "first" + Neo-Latin actinium from Greek ἀκτίς (gen.: ἀκτῖνος) "ray" + Latin -ium.[58] | ||||

| 92 | Uranium | U | Greek via Latin | Οὐρανός (Ouranos); Uranus | sky | astrological; mythological | Named after the planet Uranus, which had been discovered eight years earlier in 1781. The planet was named after the god Uranus, the god of sky and heaven in Greek mythology.[2] | ||||

| 93 | Neptunium | Np | Latin | Neptunus | Neptune | astrological; mythological | Named for Neptune, the planet. (The planet was named after the god Neptune, the god of oceans in Roman mythology.)[2] | ||||

| 94 | Plutonium | Pu | Greek via Latin | Πλούτων (Ploutōn) via Pluto | god of wealth[59] | astrological; mythological | Named after Pluto, the dwarf planet, because it was discovered directly after Neptunium and is higher than Uranium in the periodic table, so by analogy with the ordering of the planets. (The planet Pluto was named after Pluto, a Greek god of the dead)[2] Πλούτων (Ploutōn) is related to the Greek word πλοῦτος (ploutos) meaning "wealth". | ||||

| 95 | Americium | Am | America | toponym: the Americas | Named for the Americas, because it was discovered in the United States (by analogy with europium) (the name of the continent America is derived from the name of the Italian navigator Amerigo Vespucci). | ||||||

| 96 | Curium | Cm | Curie, Marie and Pierre | eponym: Pierre and Marie Curie and the -um ending | Named in honour of Marie and Pierre Curie, who discovered radium and researched radioactivity. | ||||||

| 97 | Berkelium | Bk | Anglo-Saxon via English | University of California, Berkeley | toponym: Berkeley, California | Named for the University of California, Berkeley, where it was discovered. Berkeley, California, was named in honour of George Berkeley. "Berkeley" is derived from Old English beorce léah, which means birch lea. | |||||

| 98 | Californium | Cf | English | California | toponym: State and University of California | Named for California, the U.S. state of California and for the University of California, Berkeley. (The origin of the state's name is disputed.) | |||||

| 99 | Einsteinium | Es | German | Einstein, Albert | German-Jewish surname, which means "one stone" | eponym | Named in honour of Albert Einstein, for his work on theoretical physics, which included the photoelectric effect. | ||||

| 100 | Fermium | Fm | Italian | Fermi, Enrico | Italian surname, from ferm- "fastener" and -i[60] | eponym | Named in honour of Enrico Fermi, who developed the first nuclear reactor, quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics. | ||||

| 101 | Mendelevium | Md | Mendeleyev, Dmitri | eponym | Named in honour of Dmitri Mendeleyev, who invented periodic table.[61] It has also been called eka-thulium.[21] | ||||||

| 102 | Nobelium | No | Nobel, Alfred | eponym | Named in honour of Alfred Nobel, who invented dynamite and instituted the Nobel Prizes foundation. | ||||||

| 103 | Lawrencium | Lr | Lawrence, Ernest O. | eponym | Named in honour of Ernest O. Lawrence, who was involved in the development of the cyclotron.

The symbol has been Lr since 1963; formerly Lw was used.[22] | ||||||

| 104 | Rutherfordium | Rf | Rutherford, Ernest | eponym | Named in honour of Baron Ernest Rutherford, who pioneered the Bohr model of the atom. Rutherfordium has also been called kurchatovium (Ku), named in honour of Igor Vasilevich Kurchatov, who helped develop understanding of the uranium chain reaction and the nuclear reactor.

Unnilquadium was used as a temporary systematic element name.[22] | ||||||

| 105 | Dubnium | Db | Russian | Дубна (Dubna) | toponym | Named for Dubna (Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, U.S.S.R.) where it was discovered. Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley proposed hahnium (Ha), in honour of Otto Hahn, for his pioneering work in radioactivity and radiochemistry, but the proposal was rejected.

Unnilpentium was used as a temporary systematic element name.[22] | |||||

| 106 | Seaborgium | Sg | Swedish via English | Seaborg, Glenn Teodor | Swedish surname, literally: "Lake Fort" | eponym | Named in honour of Glenn T. Seaborg, who discovered the chemistry of the transuranium elements, shared in the discovery and isolation of ten elements, and developed and proposed the actinide series. Other names: eka-tungsten[21] and temporarily by IUPAC unnilhexium (Unh).[22] | ||||

| 107 | Bohrium | Bh | Bohr, Niels | eponym: Niels Bohr | Named in honour of Niels Bohr, who made fundamental contributions to the understanding of atomic structure and quantum mechanics.[22]

Unnilseptium was used as a temporary systematic element name. | ||||||

| 108 | Hassium | Hs | Latin | Hassia | Hesse | toponym | Derived from Latin Hassia, which means Hesse, the German state where it was discovered (at the Institute for Heavy Ion Research, Darmstadt).[22] It has also been called eka-osmium[21] and temporarily by IUPAC unniloctium (Uno). | ||||

| 109 | Meitnerium | Mt | Meitner, Lise | eponym | Named in honour of Lise Meitner, who shared discovery of nuclear fission.[22] It has also been called eka-iridium[21] and temporarily by IUPAC unnilennium (Une). | ||||||

| 110 | Darmstadtium | Ds | German | Darmstadt | proper name, literally: "intestine city" | toponym | Named for Darmstadt, where it was discovered (GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research, located in Wixhausen, a small suburb north of Darmstadt). It has also been called eka-platinum and temporarily by IUPAC ununnilium (Uun).[62][21] | ||||

| 111 | Roentgenium | Rg | Röntgen, Wilhelm Conrad | eponym | Named in honour of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who produced and detected X-rays. It has also been called eka-gold[21] and temporarily by IUPAC unununium (Uuu). | ||||||

| 112 | Copernicium | Cn | Polish via Latin | Copernicus, Nicolaus | Polish surname, literally: "copper nickel" | eponym: Nicolaus Copernicus | Named in honour of Nicolaus Copernicus. Ununbium was used as a temporary systematic element name, and it was referred to as eka-mercury. | ||||

| 113 | Nihonium | Nh | Japanese | 日本 (Nihon) | Japan | toponym | Named after Japan, where the element was discovered. It has also been called eka-thallium[21] and temporarily by IUPAC ununtrium (Uut). | ||||

| 114 | Flerovium | Fl | Russian | Flerov, Georgy | Russian surname | eponym | Named in honour of Georgy Flyorov, who was at the forefront of Soviet nuclear physics and founder of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, where the element was discovered.

Ununquadium was used as a temporary systematic element name. | ||||

| 115 | Moscovium | Mc | Latin | Moscovia | Moscow | toponym | Named after Moscow Oblast, where the element was discovered. It has also been called eka-bismuth[21] and temporarily by IUPAC ununpentium (Uup). | ||||

| 116 | Livermorium | Lv | English | Livermore, Lawrence | toponym | Named in honour of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which collaborated in the discovery and is in Livermore, California, in turn named after the rancher Robert Livermore.

Ununhexium was used as a temporary systematic element name. | |||||

| 117 | Tennessine | Ts | Cherokee via English | Tennessee | Tennessee | toponym | Named after Tennessee (itself named after the Cherokee village of ᏔᎾᏏ /tanasi/), where important work for one of the steps to synthesise the element was done. It has also been called eka-astatine[21] and temporarily by IUPAC ununseptium (Uus). | ||||

| 118 | Oganesson | Og | Russian | Оганесян (Oganessian) | Yuri Oganessian | eponym | Named after Yuri Oganessian, a great contributor to the field of synthesizing superheavy elements. It has also been called eka-radon[21] and temporarily by IUPAC ununoctium (Uuo). | ||||

References

- Harper, Douglas. "hydrogen". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Some elements (particularly ancient elements) were associated with Greek (or Roman or other) gods or people, in Greek mythology (or other mythology), and with planets (or other objects in the solar system), such as Mercury (mythology) – Mercury (planet) – Mercury (element), etc.

Also, astrological symbols for the planets were often used as symbols for the ancient elements. - At one time, beryllium was called glucinium, which is from Greek γλυκύς (glykys), which means "sweet", due to the sweet taste of its salts.

- "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: beryl". Houghton Mifflin Company. 2000. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- "Beryl in Online Etymological Dictionary, accessed March 9, 2010". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Harper, Douglas. "carbon". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "nitrogen". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Nitrogen, The pure gas is inert enough that Antoine Lavoisier referred to it as "azote", meaning "without life", since animals placed in it died of asphyxiation. This term became the French for nitrogen and later spread to many other languages.

- Harper, Douglas. "oxygen". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "soda". soda. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- In medieval Europe, sodanum is the Latin name of "a compound of sodium".

- Vygus, Mark (April 2012). Vygus dictionary (PDF). p. 1546.

- "Aluminum in Online Etymological Dictionary, accessed March 9, 2010". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Harper, Douglas. "phosphorus". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Mallory & Adams (2006) The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world, Oxford University Press

- Harper, Douglas. "Sulfur". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "chlorine". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "potash". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "Potassium". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "calcium". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Previous to the discovery of some unknown elements, Prof. Dmitri Mendeleev predicted and described most of their properties; with these, he was able to accurately place them in the gaps in his periodic table. The properties of four predicted elements, eka-boron (Eb), eka-aluminium (El), eka-manganese (Em), and eka-silicon (Es), proved to be good predictors of scandium, gallium, technetium and germanium, respectively. The prefix eka-, from the Sanskrit, means "one" (one place down from a known element in the table), and is sometimes used in discussions about undiscovered elements. For example, unbiunium is sometimes referred to as eka-actinium; see also: Mendeleev's predicted elements

- see List of chemical elements naming controversies

- Harper, Douglas. "chromium". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "iron". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "nickel". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "copper". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "arsenic". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Harper, Douglas. "bromine". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Gemoll W, Vretska K (1997). Griechisch-Deutsches Schul- und Handwörterbuch (Greek–German dictionary), 9th ed. öbvhpt. ISBN 3-209-00108-1.

- Pearse, Roger (2002-09-16). "Syriac Literature". Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996-01-01). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9780802078209.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Tin – The American Heritage Dictionary

- "Antimony | Define Antimony at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Vygus, Mark (April 2012). Vygus dictionary (PDF). p. 1409.

- Antimony,

- LSJ, s.v., vocalisation, spelling, and declension vary; Endlich; Celsus, 6.6.6 ff; Pliny Natural History 33.33; Lewis and Short: Latin Dictionary. OED, s. antimony.

- stimmi is used by the Attic tragic poets of the 5th century BC. Later Greeks also used στίβι (stibi), which is written in Latin by Celsus and Pliny in the first century AD. Pliny also names stimi [sic], larbaris, alabaster (Greek: ἀλάβαστρον), "very common platyophthalmos (πλατυόφθαλμος)", "wide-eye" in Greek (the description refers to the effects of the cosmetic). In Egyptian hieroglyphics, mśdmt; the vowels are uncertain, but in Coptic and according to an Arabic tradition, it is pronounced mesdemet (Albright; Sarton, quotes Meyerhof, the translator). In Arabic, the word for powdered stibnite is kuhl.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Mike Campbell. "Meaning, Origin and History of the Name Ceres". Behind the Name. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Neodymium is frequently misspelled as neodynium

- The ancient Greek derivation of Prometheus from the Greek πρό pro ("before") + μανθάνω manthano ("learn"), thus "forethought", which engendered a contrasting brother Epimetheus ("afterthought"), was a folk etymology; it is succinctly expressed in Servius' commentary on Virgil, Eclogue 6.42: "Prometheus vir prudentissimus fuit, unde etiam Prometheus dictus est ἀπὸ τής πρόμηθείας, id est a providentia." Modern scientific linguistics suggests that the name derived from the Proto-Indo-European root that also produces the Vedic pra math, "to steal," hence pramathyu-s, "thief", cognate with "Prometheus", the thief of fire. The Vedic myth of fire's theft by Mātariśvan is an analog to the Greek account. Pramantha was the tool used to create fire. See: Fortson, Benjamin W. (2004). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing, p. 27.; Williamson (2004), The Longing for Myth in Germany, 214–15; Dougherty, Carol (2006). Prometheus. p. 4.

- Pyykkö, Pekka (2015-07-23). "Magically magnetic gadolinium". Nature Chemistry. 7 (8): 680. Bibcode:2015NatCh...7..680P. doi:10.1038/nchem.2287. PMID 26201746.

- "Thule in Wordnik, accessed March 9, 2010". Wordnik.com. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Woods, Ian (2004). The Elements: Platinum. The Elements. Benchmark Books. ISBN 978-0-7614-1550-3.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Gold in Sanskrit is ज्वल jval; in Greek, χρυσός (khrusos); in Chinese, 金 (jīn).

- Mercury – The Indian alchemy called Rassayana, which means "the way of mercury".

- Lead, Lead was mentioned in the Book of Exodus. Alchemists believed that lead was the oldest metal and associated the element with Saturn.

- Astatine, An earlier proposed name for astatine was alabamine (Ab)

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Protactinium; In 1913, Kasimir Fajans and Otto H. Göhring identified and named element 91 brevium, from Latin brevis, which means "brief, short"; protactinium has a short half-life. The name was changed to "protoactinium" in 1918 and shortened to protactinium in 1949.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- Derived from a Latin masculine genitive.

- Mendelevium, "Mendeleyev" commonly spelt as Mendeleev, Mendeléef, or Mendelejeff, and first name sometimes spelt as Dmitry or Dmitriy

- Darmstadtium, Some humorous scientists suggested the name policium, because 110 is the emergency telephone number for the German police.

Further reading

- Eric Scerri, The Periodic System, Its Story and Its Significance, Oxford University Press, New York, 2007.