List of elements by stability of isotopes

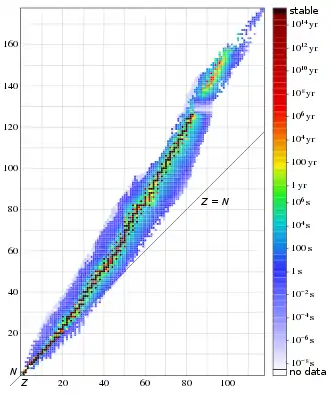

Atomic nuclei consist of protons and neutrons, which attract each other through the nuclear force, while protons repel each other via the electric force due to their positive charge. These two forces compete, leading to some combinations of neutrons and protons being more stable than others. Neutrons stabilize the nucleus, because they attract protons, which helps offset the electrical repulsion between protons. As a result, as the number of protons increases, an increasing ratio of neutrons to protons is needed to form a stable nucleus; if too many or too few neutrons are present with regard to the optimum ratio, the nucleus becomes unstable and subject to certain types of nuclear decay. Unstable isotopes decay through various radioactive decay pathways, most commonly alpha decay, beta decay, or electron capture. Many rare types of decay, such as spontaneous fission or cluster decay, are known. (See Radioactive decay for details.)

Of the first 82 elements in the periodic table, 80 have isotopes considered to be stable.[1] The 83rd element, bismuth, was traditionally regarded as having the heaviest stable isotope, bismuth-209, but in 2003 researchers in Orsay, France, measured the half-life of 209

Bi

to be 1.9×1019 years.[2][3] Technetium and promethium (atomic numbers 43 and 61, respectively[a]) and all the elements with an atomic number over 82 only have isotopes that are known to decompose through radioactive decay. No undiscovered elements are expected to be stable; therefore, lead is considered the heaviest stable element. However, it is possible that some isotopes that are now considered stable will be revealed to decay with extremely long half-lives (as with 209

Bi

). This list depicts what is agreed upon by the consensus of the scientific community as of 2019.[1]

For each of the 80 stable elements, the number of the stable isotopes is given. Only 90 isotopes are expected to be perfectly stable, and an additional 162 are energetically unstable, but have never been observed to decay. Thus, 252 isotopes (nuclides) are stable by definition (including tantalum-180m, for which no decay has yet been observed). Those that may in the future be found to be radioactive are expected to have half-lives longer than 1022 years (for example, xenon-134).

In April 2019 it was announced that the half-life of xenon-124 had been measured to 1.8 × 1022 years. This is the longest half-life directly measured for any unstable isotope;[4] only the half-life of tellurium-128 is longer.

Of the chemical elements, only one element (tin) has 10 such stable isotopes, five have seven isotopes, eight have six isotopes, ten have five isotopes, nine have four isotopes, five have three stable isotopes, 16 have two stable isotopes, and 26 have a single stable isotope.[1]

Additionally, about 30 nuclides of the naturally occurring elements have unstable isotopes with a half-life larger than the age of the Solar System (~109 years or more).[b] An additional four nuclides have half-lives longer than 100 million years, which is far less than the age of the solar system, but long enough for some of them to have survived. These 34 radioactive naturally occurring nuclides comprise the radioactive primordial nuclides. The total number of primordial nuclides is then 252 (the stable nuclides) plus the 34 radioactive primordial nuclides, for a total of 286 primordial nuclides. This number is subject to change if new shorter-lived primordials are identified on Earth.

One of the primordial nuclides is tantalum-180m, which is predicted to have a half-life in excess of 1015 years, but has never been observed to decay. The even-longer half-life of 2.2 × 1024 years of tellurium-128 was measured by a unique method of detecting its radiogenic daughter xenon-128 and is the longest known experimentally measured half-life.[5] Another notable example is the only naturally occurring isotope of bismuth, bismuth-209, which has been predicted to be unstable with a very long half-life, but has been observed to decay. Because of their long half-lives, such isotopes are still found on Earth in various quantities, and together with the stable isotopes they are called primordial isotope. All the primordial isotopes are given in order of their decreasing abundance on Earth.[c]. For a list of primordial nuclides in order of half-life, see List of nuclides.

118 chemical elements are known to exist. All elements to element 94 are found in nature, and the remainder of the discovered elements are artificially produced, with isotopes all known to be highly radioactive with relatively short half-lives (see below). The elements in this list are ordered according to the lifetime of their most stable isotope.[1] Of these, three elements (bismuth, thorium, and uranium) are primordial because they have half-lives long enough to still be found on the Earth,[d] while all the others are produced either by radioactive decay or are synthesized in laboratories and nuclear reactors. Only 13 of the 38 known-but-unstable elements have isotopes with a half-life of at least 100 years. Every known isotope of the remaining 25 elements is highly radioactive; these are used in academic research and sometimes in industry and medicine.[e] Some of the heavier elements in the periodic table may be revealed to have yet-undiscovered isotopes with longer lifetimes than those listed here.[f]

About 338 nuclides are found naturally on Earth. These comprise 252 stable isotopes, and with the addition of the 34 long-lived radioisotopes with half-lives longer than 100 million years, a total of 286 primordial nuclides, as noted above. The nuclides found naturally comprise not only the 286 primordials, but also include about 52 more short-lived isotopes (defined by a half-life less than 100 million years, too short to have survived from the formation of the Earth) that are daughters of primordial isotopes (such as radium from uranium); or else are made by energetic natural processes, such as carbon-14 made from atmospheric nitrogen by bombardment from cosmic rays.

Elements by number of primordial isotopes

An even number of protons or neutrons is more stable (higher binding energy) because of pairing effects, so even–even nuclides are much more stable than odd–odd. One effect is that there are few stable odd–odd nuclides: in fact only five are stable, with another four having half-lives longer than a billion years.

Another effect is to prevent beta decay of many even–even nuclides into another even–even nuclide of the same mass number but lower energy, because decay proceeding one step at a time would have to pass through an odd–odd nuclide of higher energy. (Double beta decay directly from even–even to even–even, skipping over an odd-odd nuclide, is only occasionally possible, and is a process so strongly hindered that it has a half-life greater than a billion times the age of the universe.) This makes for a larger number of stable even–even nuclides, up to three for some mass numbers, and up to seven for some atomic (proton) numbers and at least four for all stable even-Z elements beyond iron.

Since a nucleus with an odd number of protons is relatively less stable, odd-numbered elements tend to have fewer stable isotopes. Of the 26 "monoisotopic" elements that have only a single stable isotope, all but one have an odd atomic number—the single exception being beryllium. In addition, no odd-numbered element has more than two stable isotopes, while every even-numbered element with stable isotopes, except for helium, beryllium, and carbon, has at least three.

Tables

The following tables give the elements with primordial nuclides, which means that the element may still be identified on Earth from natural sources, having been present since the Earth was formed out of the solar nebula. Thus, none are shorter-lived daughters of longer-lived parental primordials, such as radon. Two nuclides which have half-lives long enough to be primordial, but have not yet been conclusively observed as such (244Pu and 146Sm), have been excluded.

The tables of elements are sorted in order of decreasing number of nuclides associated with each element. (For a list sorted entirely in terms of half-lives of nuclides, with mixing of elements, see List of nuclides.) Stable and unstable (marked decays) nuclides are given, with symbols for unstable (radioactive) nuclides in italics. Note that the sorting does not quite give the elements purely in order of stable nuclides, since some elements have a larger number of long-lived unstable nuclides, which place them ahead of elements with a larger number of stable nuclides. By convention, nuclides are counted as "stable" if they have never been observed to decay by experiment or from observation of decay products (extremely long-lived nuclides unstable only in theory, such as tantalum-180m, are counted as stable).

The first table is for even-atomic numbered elements, which tend to have far more primordial nuclides, due to the stability conferred by proton-proton pairing. A second separate table is given for odd-atomic numbered elements, which tend to have far fewer stable and long-lived (primordial) unstable nuclides.

| Z |

Element |

Stable [1] |

Decays [b][1] |

unstable in italics[b] odd neutron number in pink | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | tin | 10 | — | 120 Sn | 118 Sn | 116 Sn | 119 Sn | 117 Sn | 124 Sn | 122 Sn | 112 Sn | 114 Sn | 115 Sn |

| 54 | xenon | 7 | 2 | 132 Xe | 129 Xe | 131 Xe | 134 Xe | 136 Xe | 130 Xe | 128 Xe | 124 Xe | 126 Xe | |

| 48 | cadmium | 6 | 2 | 114 Cd | 112 Cd | 111 Cd | 110 Cd | 113 Cd | 116 Cd | 106 Cd | 108 Cd | ||

| 52 | tellurium | 6 | 2 | 130 Te | 128 Te | 126 Te | 125 Te | 124 Te | 122 Te | 123 Te | 120 Te | ||

| 44 | ruthenium | 7 | — | 102 Ru | 104 Ru | 101 Ru | 99 Ru | 100 Ru | 96 Ru | 98 Ru | |||

| 66 | dysprosium | 7 | — | 164 Dy | 162 Dy | 163 Dy | 161 Dy | 160 Dy | 158 Dy | 156 Dy | |||

| 70 | ytterbium | 7 | — | 174 Yb | 172 Yb | 173 Yb | 171 Yb | 176 Yb | 170 Yb | 168 Yb | |||

| 80 | mercury | 7 | — | 202 Hg | 200 Hg | 199 Hg | 201 Hg | 198 Hg | 204 Hg | 196 Hg | |||

| 42 | molybdenum | 6 | 1 | 98 Mo | 96 Mo | 95 Mo | 92 Mo | 100 Mo | 97 Mo | 94 Mo | |||

| 56 | barium | 6 | 1 | 138 Ba | 137 Ba | 136 Ba | 135 Ba | 134 Ba | 132 Ba | 130 Ba | |||

| 64 | gadolinium | 6 | 1 | 158 Gd | 160 Gd | 156 Gd | 157 Gd | 155 Gd | 154 Gd | 152 Gd | |||

| 76 | osmium | 6 | 1 | 192 Os | 190 Os | 189 Os | 188 Os | 187 Os | 186 Os | 184 Os | |||

| 60 | neodymium | 5 | 2 | 142 Nd | 144 Nd | 146 Nd | 143 Nd | 145 Nd | 148 Nd | 150 Nd | |||

| 62 | samarium | 5 | 2 | 152 Sm | 154 Sm | 147 Sm | 149 Sm | 148 Sm | 150 Sm | 144 Sm | |||

| 46 | palladium | 6 | — | 106 Pd | 108 Pd | 105 Pd | 110 Pd | 104 Pd | 102 Pd | ||||

| 68 | erbium | 6 | — | 166 Er | 168 Er | 167 Er | 170 Er | 164 Er | 162 Er | ||||

| 20 | calcium | 5 | 1 | 40 Ca | 44 Ca | 42 Ca | 48 Ca | 43 Ca | 46 Ca | ||||

| 34 | selenium | 5 | 1 | 80 Se | 78 Se | 76 Se | 82 Se | 77 Se | 74 Se | ||||

| 36 | krypton | 5 | 1 | 84 Kr | 86 Kr | 82 Kr | 83 Kr | 80 Kr | 78 Kr | ||||

| 72 | hafnium | 5 | 1 | 180 Hf | 178 Hf | 177 Hf | 179 Hf | 176 Hf | 174 Hf | ||||

| 78 | platinum | 5 | 1 | 195 Pt | 194 Pt | 196 Pt | 198 Pt | 192 Pt | 190 Pt | ||||

| 22 | titanium | 5 | — | 48 Ti | 46 Ti | 47 Ti | 49 Ti | 50 Ti | |||||

| 28 | nickel | 5 | — | 58 Ni | 60 Ni | 62 Ni | 61 Ni | 64 Ni | |||||

| 30 | zinc | 5 | — | 64 Zn | 66 Zn | 68 Zn | 67 Zn | 70 Zn | |||||

| 32 | germanium | 4 | 1 | 74 Ge | 72 Ge | 70 Ge | 73 Ge | 76 Ge | |||||

| 40 | zirconium | 4 | 1 | 90 Zr | 94 Zr | 92 Zr | 91 Zr | 96 Zr | |||||

| 74 | tungsten | 4 | 1 | 184 W | 186 W | 182 W | 183 W | 180 W | |||||

| 16 | sulfur | 4 | — | 32 S | 34 S | 33 S | 36 S | ||||||

| 24 | chromium | 4 | — | 52 Cr | 53 Cr | 50 Cr | 54 Cr | ||||||

| 26 | iron | 4 | — | 56 Fe | 54 Fe | 57 Fe | 58 Fe | ||||||

| 38 | strontium | 4 | — | 88 Sr | 86 Sr | 87 Sr | 84 Sr | ||||||

| 58 | cerium | 4 | — | 140 Ce | 142 Ce | 138 Ce | 136 Ce | ||||||

| 82 | lead | 4 | — | 208 Pb | 206 Pb | 207 Pb | 204 Pb | ||||||

| 8 | oxygen | 3 | — | 16 O | 18 O | 17 O | |||||||

| 10 | neon | 3 | — | 20 Ne | 22 Ne | 21 Ne | |||||||

| 12 | magnesium | 3 | — | 24 Mg | 26 Mg | 25 Mg | |||||||

| 14 | silicon | 3 | — | 28 Si | 29 Si | 30 Si | |||||||

| 18 | argon | 3 | — | 40 Ar | 36 Ar | 38 Ar | |||||||

| 2 | helium | 2 | — | 4 He | 3 He | ||||||||

| 6 | carbon | 2 | — | 12 C | 13 C | ||||||||

| 92 | uranium | 0 | 2 | 238 U [d] | 235 U | ||||||||

| 4 | beryllium | 1 | — | 9 Be | |||||||||

| 90 | thorium | 0 | 1 | 232 Th [d] | |||||||||

| Z |

Element |

Stab |

Dec |

unstable: italics odd N in pink | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | potassium | 2 | 1 | 39 K | 41 K | 40 K |

| 1 | hydrogen | 2 | — | 1 H | 2 H | |

| 3 | lithium | 2 | — | 7 Li | 6 Li | |

| 5 | boron | 2 | — | 11 B | 10 B | |

| 7 | nitrogen | 2 | — | 14 N | 15 N | |

| 17 | chlorine | 2 | — | 35 Cl | 37 Cl | |

| 29 | copper | 2 | — | 63 Cu | 65 Cu | |

| 31 | gallium | 2 | — | 69 Ga | 71 Ga | |

| 35 | bromine | 2 | — | 79 Br | 81 Br | |

| 47 | silver | 2 | — | 107 Ag | 109 Ag | |

| 51 | antimony | 2 | — | 121 Sb | 123 Sb | |

| 73 | tantalum | 2 | — | 181 Ta | 180m Ta | |

| 77 | iridium | 2 | — | 193 Ir | 191 Ir | |

| 81 | thallium | 2 | — | 205 Tl | 203 Tl | |

| 23 | vanadium | 1 | 1 | 51 V | 50 V | |

| 37 | rubidium | 1 | 1 | 85 Rb | 87 Rb | |

| 49 | indium | 1 | 1 | 115 In | 113 In | |

| 57 | lanthanum | 1 | 1 | 139 La | 138 La | |

| 63 | europium | 1 | 1 | 153 Eu | 151 Eu | |

| 71 | lutetium | 1 | 1 | 175 Lu | 176 Lu | |

| 75 | rhenium | 1 | 1 | 187 Re | 185 Re | |

| 9 | fluorine | 1 | — | 19 F | ||

| 11 | sodium | 1 | — | 23 Na | ||

| 13 | aluminium | 1 | — | 27 Al | ||

| 15 | phosphorus | 1 | — | 31 P | ||

| 21 | scandium | 1 | — | 45 Sc | ||

| 25 | manganese | 1 | — | 55 Mn | ||

| 27 | cobalt | 1 | — | 59 Co | ||

| 33 | arsenic | 1 | — | 75 As | ||

| 39 | yttrium | 1 | — | 89 Y | ||

| 41 | niobium | 1 | — | 93 Nb | ||

| 45 | rhodium | 1 | — | 103 Rh | ||

| 53 | iodine | 1 | — | 127 I | ||

| 55 | caesium | 1 | — | 133 Cs | ||

| 59 | praseodymium | 1 | — | 141 Pr | ||

| 65 | terbium | 1 | — | 159 Tb | ||

| 67 | holmium | 1 | — | 165 Ho | ||

| 69 | thulium | 1 | — | 169 Tm | ||

| 79 | gold | 1 | — | 197 Au | ||

| 83 | bismuth | 0 | 1 | 209 Bi | ||

Elements with no primordial isotopes

| Z |

Element |

t1⁄2[g][1] | Longest- lived isotope |

|---|---|---|---|

| 94 | plutonium | 8.08×107 yr | 244 Pu |

| 96 | curium | 1.56×107 yr | 247 Cm |

| 43 | technetium | 4.21×106 yr | 97 Tc [a] |

| 93 | neptunium | 2.14×106 yr | 237 Np |

| 91 | protactinium | 32,760 yr | 231 Pa |

| 95 | americium | 7,370 yr | 243 Am |

| 88 | radium | 1,600 yr | 226 Ra |

| 97 | berkelium | 1,380 yr | 247 Bk |

| 98 | californium | 900 yr | 251 Cf |

| 84 | polonium | 125 yr | 209 Po |

| 89 | actinium | 21.772 yr | 227 Ac |

| 61 | promethium | 17.7 yr | 145 Pm [a] |

| 99 | einsteinium | 1.293 yr | 252 Es [f] |

| 100 | fermium | 100.5 d | 257 Fm [f] |

| 101 | mendelevium | 51.3 d | 258 Md [f] |

| 86 | radon | 3.823 d | 222 Rn |

| 105 | dubnium | 1.2 d | 268 Db [f] |

| Z |

Element |

t1⁄2[g][1] | Longest- lived isotope |

|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | lawrencium | 11 h | 266 Lr [f] |

| 85 | astatine | 8.1 h | 210 At |

| 104 | rutherfordium | 1.3 h | 267 Rf [f] |

| 102 | nobelium | 58 min | 259 No [f] |

| 87 | francium | 22 min | 223 Fr |

| 106 | seaborgium | 14 min | 269 Sg [f] |

| 111 | roentgenium | 1.7 min | 282 Rg [f] |

| 107 | bohrium | 1 min | 270 Bh [f] |

| 112 | copernicium | 28 s | 285 Cn [f] |

| 108 | hassium | 16 s | 269 Hs [f] |

| 110 | darmstadtium | 12.7 s | 281 Ds [f] |

| 113 | nihonium | 9.5 s | 286 Nh [f] |

| 109 | meitnerium | 4.5 s | 278 Mt [f] |

| 114 | flerovium | 1.9 s | 289 Fl [f] |

| 115 | moscovium | 650 ms | 290 Mc [f] |

| 116 | livermorium | 57 ms | 293 Lv [f] |

| 117 | tennessine | 51 ms | 294 Ts [f] |

| 118 | oganesson | 690 μs | 294 Og [f] |

See also

Footnotes

- a See Stability of technetium isotopes for a detailed discussion as to why technetium and promethium have no stable isotopes.

- b Isotopes that have a half-life of more than about 108 yr may still be found on Earth, but only those with half-lives above 7×108 yr (as of 235U) are found in appreciable quantities. The present list neglects a few isotopes with half-lives about 108 yr because they have been measured in tiny quantities on Earth. Uranium-234 with its half-life of 246,000 yr and natural isotopic abundance 0.0055% is a special case: it is a decay product of uranium-238 rather than a primordial nuclide.

- c There are unstable isotopes with extremely long half-lives that are also found on Earth, and some of them are even more abundant than all the stable isotopes of a given element (for example, beta-active 187Re is twice as abundant as stable 185Re). Also, a bigger natural abundance of an isotope just implies that its formation was favored by the stellar nucleosynthesis process that produced the matter now constituting the Earth (and, of course, the rest of the Solar System) (see also Formation and evolution of the Solar System).

- d While bismuth has only one primordial isotope, uranium has three isotopes that are found in nature in significant amounts (238

U

, 235

U

, and 234

U

; the first two are primordial, while 234U is radiogenic), and thorium has two (primordial 232

Th

and radiogenic 230

Th

). - e See many different industrial and medical applications of radioactive elements in Radionuclide, Nuclear medicine, Common beta emitters, Commonly used gamma-emitting isotopes, Fluorine-18, Cobalt-60, Strontium-90, Technetium-99m, Iodine-123, Iodine-124, Promethium-147, Iridium-192, etc.

- f For elements with a higher atomic number than californium (with Z>98), there might exist undiscovered isotopes that are more stable than the known ones.

- g Legend: a=year, d=day, h=hour, min=minute, s=second.

References

- Sonzogni, Alejandro. "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center: Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- Marcillac, Pierre de; Noël Coron; Gérard Dambier; Jacques Leblanc & Jean-Pierre Moalic (2003). "Experimental detection of α-particles from the radioactive decay of natural bismuth". Nature. 422 (6934): 876–878. Bibcode:2003Natur.422..876D. doi:10.1038/nature01541. PMID 12712201.

- Dumé, Belle (2003-04-23). "Bismuth breaks half-life record for alpha decay". Institute of Physics Publishing.

- Siegel, Ethan. "Dark Matter Search Discovers A Spectacular Bonus: The Longest-Lived Unstable Element Ever". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- "Noble Gas Research". Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2013-01-10. Novel Gas Research. Accessed April 26, 2009