Riau Islands

The Riau Islands (Indonesian: Kepulauan Riau) is a province of Indonesia. It comprises a total of 1,796 islands scattered between the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, and Borneo.[4] Situated on one of the world's busiest shipping lanes along the Malacca Strait and the South China Sea, the province shares water borders with neighboring countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei. The Riau Islands also has a relatively large potential of mineral resources, energy, as well as marine resources.[5] The capital of the province is Tanjung Pinang and the largest city is Batam.

Riau Islands | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Coordinates: 3°56′N 108°09′E | |

| Established | 24 September 2002 |

| Capital | Tanjung Pinang |

| Largest city | Batam |

| Divisions | 9 regencies and cities, 70 districts, 416 villages |

| Government | |

| • Body | Riau Islands Provincial Government |

| • Governor | Isdianto |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10,595.41 km2 (4,090.91 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 31st in Indonesia |

| Elevation | 2−5 m (−14 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,165 m (3,822 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (mid 2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 2,241,570 |

| • Rank | 27th in Indonesia |

| • Density | 210/km2 (550/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 10th in Indonesia |

| Demographics (2010)[2] | |

| • Ethnic groups |

|

| • Religion |

|

| • Languages | Indonesian (official) Malay (regional) Other languages: Javanese, Minangkabau, Batak, Buginese, Banjarese, Chinese |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| ISO 3166 code | ID-KR |

| Vehicle registration | BP |

| HDI | |

| HDI rank | 4th in Indonesia (2019) |

| GRP Nominal | |

| GDP PPP (2019) | |

| GDP rank | 12th in Indonesia (2019) |

| Nominal per capita | US$ 8,658 (2019)[3] |

| PPP per capita | US$ 28,460 (2019)[3] |

| Per capita rank | 4th in Indonesia (2019) |

| Website | kepriprov |

The Riau archipelago was once part of the Johor Sultanate, which was later partitioned between the Dutch East Indies and British Malaya after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, in which the archipelago fell under Dutch influence.[6] A Dutch protectorate, the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, was established in the region between 1824 and 1911 before being directly ruled by the Dutch East Indies.[7] The archipelago became a part of Indonesia following the occupation of the Japanese Empire (1942–1945) and the Indonesian National Revolution (1945–1949). The Riau Islands separated from the province of Riau in September 2002, becoming Indonesia's third-youngest province.

A free trade zone of the Indonesia–Malaysia–Singapore Growth Triangle, the Riau Islands has experienced rapid industrialisation since the 1970s. The Riau Islands is one of the country's most prosperous provinces, having a GDP per capita of Rp 72,571.75 (US$8,300.82) as of 2011, the fourth largest among all provinces in Indonesia after East Kalimantan, Jakarta and Riau.[8] In addition, as of 2018, the Riau Islands has a Human Development Index of 0.748, also the fourth largest among all provinces in Indonesia after Jakarta, Special Region of Yogyakarta and East Kalimantan.[9]

The population of the Riau Islands is heterogeneous and is highly diverse in ethnicity, culture, language and religion. The province is home to different ethnic groups such as the Malays, Chinese, Javanese, Minangkabau and others. Economic rise in the region has attracted many immigrants and labors from other parts of Indonesia.[10] The area around Batam is also home to many expatriates from different countries. Approximately 80% of these are from other Asian countries, with most of the westerners coming from the United Kingdom, rest of Europe, Australia and the United States. The province also has the second largest number of foreign tourist arrivals in Indonesia, after Bali.[11]

History

Etymology

There are several possible origins of the word riau. The first possible origins is that riau is derived from the Portuguese word rio, which means river.[12][13] After the fall of the Malacca Sultanate in the early 16th century, the remaining Malaccan nobles and subjects fled from Malacca to mainland Sumatra while being pursued by the Portuguese. The Portuguese is believed to have reached as far as the Siak River.[14]

The second version claims that riau comes from the word riahi which means sea water. The word is allegedly derived from the figure of Sinbad al-Bahar in the book of the One Thousand and One Nights.[13]

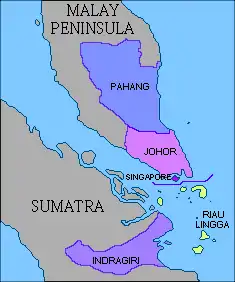

Another version is that riau is derived from the Malay word riuh, which means crowded, frenzied working people. This word is believed used to reflect the nature of the Malay people in present-day Bintan. The name is likely to have become famous since Raja Kecil moved the Malay kingdom center from Johor to Ulu Riau in 1719.[13] This name was used as one of the four main sultanates that formed the kingdoms of Riau, Lingga, Johor and Pahang. However, as the consequences of the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 between the Netherlands and United Kingdom, the Johor-Pahang sultanates fell under British influence, while the Riau-Lingga sultanates fell under Dutch influence.[15][16]

Pre-sultanate era

![]() Sultanate of Riau-Lingga 1823–1911

Sultanate of Riau-Lingga 1823–1911

![]() Dutch East Indies 1911–1942; 1945–1949

Dutch East Indies 1911–1942; 1945–1949

![]() Empire of Japan 1942–1945

Empire of Japan 1942–1945

![]() United States of Indonesia 1949–1950

United States of Indonesia 1949–1950

Due to its strategic location and size, the Riau Archipelago has a rich history. Riau has for centuries been the home of Malay and Orang Laut people (sea nomads). Later migrants came from southern China and Indochina, today people from a large region of Asia has settled here. The Riau archipelago was located aside the China-India maritime trading route, and was early in the 14th century, together with Temasek (Singapore), recorded in Chinese maritime records as one of Riau archipelago's islands that was inhabited by Malay pirates.[17]

As much as two of three hundred ships was used to force Chinese ships returning from the Indian Ocean to their harbors and to attack those who resisted. Large quantities of Chinese ceramics have been recovered on Bintan, some date back to the early Song dynasty (960–1127).[18] An Arabian explorer, Ibnu Battuta, wrote about Riau in the 13th century: "Here there are little islands, from which armed black pirates with poised arrows emerged, possessing armed warships; they plunder people but do not enslave them."[19] Log records of Chinese ships testify these incidents in the 12th century. Even after several centuries, the Riau archipelago, especially Bintan, is still referred by many by the epithet "Pirate Island".[20]

During the 12th to 13th century, the Riau archipelago was a part of Srivijaya Empire on Sumatra. Sri Tri Buana, a member of the royal family of Palembang, visited Riau in 1290. The Queen of Bintan met him, and he combined flotilla of 800 vessels sailed for Bintan where he later became a king. It is also said that it was he who gave name to Singapore. Upon landing on Temasek, the old name of Singapore, he spotted an animal, which he thought was a lion, and renamed Temasek as Singapura (Lion City). He also proclaimed himself as a king of Singapore.[21][20]

According to the Malay Annals, a Srivijaya prince named Seri Teri Buana, fleeing from the sacking of Palembang, stayed on Bintan for several years, gathering his strength before founding the Kingdom of Singapura (Singapore).[22]

Sultanate era

During the rule of Sultan Mansur Shah (1459–1466), the Riau archipelago became the part of the Malacca Sultanate. The Malacca Sultanate then included Kedah, Trengganu, Pahang, Johore, Jambi, Kampar, Bengkalis, Karimun Islands and Bintan. The fall of Malacca Empire started in 1511 when Malacca fell to the Portuguese. Sultan Mahmud Shah fled to Pahang and then to Johor and Bintan in 1521.[23][24] There, he held out against Portuguese attacks, he even laid siege on Malacca in 1524, before a Portuguese counterattack forced him to flee to Sumatra where he died in 1528.[25] Sultan Alauddin succeeded his father and made a new capital in the south. His realm was the Johor Sultanate, the successor of Malacca. The archipelago became the part of "war triangle" between the Portuguese, the Johor Sultanate and the Achehnese of northern Sumatra.

Bintan may have seen many rulers during this time, as the three parties grew and declined in power. Subsequently, the Portuguese attacked Johor in 1587.[26] The battle, known as the Siege of Johor, resulted in the Portuguese emerging victorious. The forces of Johor were incapable of preventing the heavy Portuguese infantry from landing and storming the city after a naval bombardment, and its Sultan was forced to retreat into the jungle in a rout.[27] The Portuguese captured ample spoils, which included over 1000 cannon, the great majority of them of small caliber, 1500 firearms, and burned upwards to 2000 craft of many sizes.[28] Following the attack, Dom Pedro de Lima (brother of Dom Paulo de Lima) also sacked Bintan, then a vassal of Johor.[29]

After the fall of Malacca in 1511, the Riau islands became the centre of political power of the mighty Sultanate of Johor or Johor-Riau, based on Bintan Island, and were for long considered the centre of Malay culture.[30] Like Malacca before it, Riau was also the centre of Islamic studies and teaching. Many orthodox scholars from the Muslim heartlands like the Indian Subcontinent and Arabia were housed in special religious hostels, while devotees of Sufism could seek initiation into one of the many Tariqah (Sufi Brotherhood) which flourished in Riau.[31] In many ways, Riau managed to recapture some of the old Malacca glory. Both became prosperous due to trade but there was a major difference; Malacca was also great due to its territorial conquest.On the northern part of Sumatra around the same period, the Aceh Sultanate was beginning to gain substantial influence over the Straits of Malacca. With the fall of Malacca to Christian hands, Muslim traders often skipped Malacca in favour of Aceh or also of Johor's capital Johor Lama (Kota Batu). Therefore, Malacca and Aceh became direct competitors. With the Portuguese and Johor frequently locking horns, Aceh launched multiple raids against both sides to tighten its grip over the straits.[32] The rise and expansion of Aceh encouraged the Portuguese and Johor to sign a truce and divert their attention to Aceh. The truce, however, was short-lived and with Aceh severely weakened, Johor and the Portuguese had each other in their sights again. During the rule of Sultan Iskandar Muda, Aceh attacked Johor in 1613 and again in 1615.[33][34]

With the fall of Portuguese Malacca in 1641 and the decline of Aceh due to the growing power of the Dutch, Johor started to re-established itself as a power along the Straits of Malacca during the reign of Sultan Abdul Jalil Shah III (1623–1677).[35] Its influence extended to Pahang, Sungei Ujong, Malacca, Klang and the Riau Archipelago.[36]

In the early 18th century, the descendants of the Sultan and the Regent of Johor where fighting for power. Bugis aristocrats from Celebes was asked to assist the Regent of Johor, and managed to achieve control of Riau due to the internal struggle between the members of the Johor Sultanate. The Bugis were great traders and made Bintan as a major trading center. Riau and Bintan also attracted British, Chinese, Dutch, Arabic and Indian traders. The Dutch however started to look upon Riau and the Bugis as a dangerous rival to Dutch trade in the region, drawing away trade from their ports in Malacca and Batavia (Jakarta). A Dutch fleet attacked Riau in 1784 but failed to hold the islands. Another attempt later the same year also failed before they managed to break the Bugis blockade of Malacca in June 1784.[37] The Bugis commander, Raja Haji was killed during battle and the Bugis units retreated, which opened the way for a Dutch counterattack on Riau. The Bugis was expelled from Bintan and Riau, and a treaty between the Dutch and the Malay sultans granted Dutch control over the area.[38] The treaty caused much anger among Malay rulers, and again in 1787 a force that was offered refuge by Sultan Mahmud drove out the Dutch. This also led to the return of the Bugis and the rivalry between Bugis and Malay. Peace between the two parties was finally reached in 1803. Around this time Sultan Mahmud gave Penyengat Island as a wedding gift to his bride, Raja Hamidah, Raja Ali Haji's daughter. Penyengat became for a period the center of government, Islamic religion and the Malay culture.[39]

Colonial rule

In 1812, the Johor-Riau Sultanate experienced a succession crisis.[41] The death of the Mahmud Shah III in Lingga left no heir apparent. Royal custom required that the succeeding sultan must be present at his predecessor's deathbed. However at the time Mahmud Shah III died, the eldest prince, Tengku Hussein, was in Pahang to celebrate his marriage to the daughter of the Bendahara (governor).[42] The other candidate was Tengku Hussein's half-brother, Tengku Abdul Rahman. To complicate matters, neither of the candidates was of full royal blood. The mother of Tengku Hussein, Cik Mariam, owed her origin to a Balinese slave lady and a Bugis commoner.[43] Tengku Abdul Rahman had a similarly lowborn mother, Cik Halimah. The only unquestionably royal wife and consort of Mahmud Shah was Engku Puteri Hamidah, whose only child had died an hour after birth.[44] In the following chaos, Engku Puteri was expected to install Tengku Hussein as the next sultan, because he had been preferred by the late Mahmud Shah. Based on the royal adat (customary observance), the consent of Engku Puteri was crucial as she was the holder of the Cogan (Royal Regalia) of Johor-Riau, and the installation of a new sultan was only valid if it took place with the regalia. The regalia was fundamental to the installation of the sultan; it was a symbol of power, legitimacy and the sovereignty of the state.[45] Nonetheless, Yang Dipertuan Muda Jaafar (then-viceroy of the sultanate) supported the reluctant Tengku Abdul Rahman, adhering to the rules of royal protocol, as he had been present at the late Sultan's deathbed.[46]

Rivalry between the British and the Dutch now came into play. The British had earlier gained Malacca from the Dutch under the Treaty of The Hague in 1795 and saw an opportunity to increase their regional influence. They crowned Tengku Hussein in Singapore, and he took the title Hussein Shah of Johor.[47][48] The British were actively involved in the Johor-Riau administration between 1812 and 1818, and their intervention further strengthened their dominance in the Strait of Malacca. The British recognised Johor-Riau as a sovereign state and offered to pay Engku Puteri 50,000 Ringgits (Spanish Coins) for the royal regalia, which she refused.[49] Seeing the diplomatic advantage gained in the region by the British, the Dutch responded by crowning Tengku Abdul Rahman as sultan instead. They also obtained, at the Congress of Vienna, a withdrawal of British recognition of Johor-Riau sovereignty.[50] To further curtail the British domination over the region, the Dutch entered into an agreement with the Johor-Riau Sultanate on 27 November 1818. The agreement stipulated that the Dutch were to be the paramount leaders of the Johor-Riau Sultanate and that only Dutch people could engage in trade with the kingdom. A Dutch garrison was then stationed in Riau.[51] The Dutch also secured an agreement that Dutch consent was required for all future appointments of Johor-Riau Sultans. This agreement was signed by Yang Dipertuan Muda Raja Jaafar representing Abdul Rahman, without the sultan's consent or knowledge.[39]

Just as the British had done, both the Dutch and Yang Dipertuan Muda then desperately tried to win the royal regalia from Engku Puteri. The reluctant Abdul Rahman, believing he was not the rightful heir, decided to move from Lingga to Terengganu, claiming that he wanted to celebrate his marriage. The Dutch, who desired to control the Johor-Riau Empire, feared losing momentum because of the absence of mere regalia. They therefore ordered Timmerman Tyssen, the Dutch Governor of Malacca, to seize Penyengat in October 1822 and remove the royal regalia from Tengku Hamidah by force. The regalia was then stored in the crown prince's fort in Tanjung Pinang. Engku Puteri was reported to have written a letter to Van Der Capellen, the Dutch Governor in Batavia, about this issue. With the royal regalia in Dutch hands, Abdul Rahman was invited from Terengganu and proclaimed as the Sultan of Johor, Riau-Lingga and Pahang on 27 November 1822. Hence, the legitimate ruler of the Johor-Riau Empire was now Abdul Rahman, rather than the British-backed Hussein.[52]

This led to the partition of Johor-Riau under the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824, by which the region north of the Singapore Strait including the island of Singapore and Johor were to be under British influence, while the south of the strait along with Riau and Lingga were to be controlled by the Dutch. By installing two sultans from the same kingdom, both the British and the Dutch effectively destroyed the Johor-Riau polity and satisfied their colonial ambitions.[53][54] Under the treaty, Tengku Abdul Rahman was crowned as the Sultan of Riau-Lingga, bearing the name of Sultan Abdul Rahman, with the royal seat in Daik, Lingga.[55] Tengku Hussein, backed by the British, was installed as the Sultan of Johore and ruled over Singapore and the Peninsular Johor.[56][48] He later ceded Singapore to the British in return for their support during the dispute. Both sultans of Johor and Riau acted mainly as Puppet monarchs under the guidance of the colonial powers.

The globalization of the 19th century opened new opportunities for the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. Proximity to cosmopolitan Singapore, just 40 miles away, shaped the political climate of the kingdom, giving Riau Malays an opportunity to familiarize themselves with new ideas from the Middle East. The opening of Suez Canal meant a journey to Mecca via Port Said, Egypt and Singapore could take no more than a fortnight; thus these cities became major ports for the Hajj pilgrimage.[57] Inspired by the experience and intellectual progress attained in the Middle East and influenced by the Pan-Islamism brotherhood, the Riau Malay intelligentsia established the Roesidijah (Club) Riouw in 1895. The association was born as a literary circle to develop the religious, cultural and intellectual needs of the sultanate, but as it matured, it changed into a more critical organisation and began to address the fight against Dutch rule in the kingdom.[58] The late 19th century was marked by growing awareness among the elite and rulers of the importance of watan (homeland) and one's duty towards his or her native soil. To succeed to establish a watan, the land must be independent and sovereign, a far-cry from a Dutch-controlled sultanate. Moreover, it was also viewed that the penetration of the west in the state was slowly tearing apart the fabric of the Malay-Muslim identity.

By the dawn of the 20th century, the association had become a political tool for rising against the colonial power, with Raja Muhammad Thahir and Raja Ali Kelana acting as its backbone. Diplomatic missions were sent to the Ottoman Empire in 1883, 1895 and in 1905 to secure the liberation of the kingdom by Raja Ali Kelana, accompanied by a renowned Pattani-born Ulema, Syeikh Wan Ahmad Fatani.[59][60] The Dutch Colonial Office in Tanjung Pinang labelled the organisation as a left-leaning party. The organisation also won momentous support from the Mohakamah (Malay Judiciary) and the Dewan Kerajaan (Sultanate Administrative Board). It critically monitored and researched every step taken by the Dutch Colonial Resident in the sultanate's administration, which outraged the Dutch.

The movement was an early form of Malay nationalism. Non-violence and passive resistance measures were adopted by the association. The main method of the movement was to hold symbolic boycotts. The Dutch then branded the movement as a passive resistance (Dutch: leidelek verset), and passive acts such as ignoring the raising of the Dutch flag were met with anger by the Batavia-based Raad van Indie (Dutch East Indies Council) and the Advisor on Native Affairs, Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje. Hurgronje wrote a secret letter to the Raad van Indie, advocating that the sultanate and association be crushed as resistance in the earlier Aceh War had been. Hurgronje justified this with several arguments, among which were that since 1902 the members of the Roesidijah Klub would gather around the royal court and refuse to raise the Dutch flag on government vessels. The Dutch Colonial Resident in Riau, A.L. Van Hasselt advised the Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies that the Sultan was an opponent to the Dutch and immersed with a group of hardcore resistant. Later, on 1 January 1903, the Dutch Colonial Resident found that the Dutch flag was not being raised during his visit to the royal palace.[61] In his report to the governor he wrote; "it seems that he (Sultan Abdul Rahman II) acted as if he was a sovereign king and he raises his own flag". Based on several records in the Indonesian National Archive, there were some reports that the Sultan then apologized to the governor over the "flag incident".[62]

On 18 May 1905, the Dutch demanded a new agreement with the sultan, stipulating further limits on the powers of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate, requiring that the Dutch flag must be raised higher than the flag of Riau, and specifying that Dutch officials should be given supreme honor in the land. The agreement further stipulated that the Riau-Lingga Sultanate was a mere loan from the Dutch Government. The agreement was drawn up due to the fact that the appointment of Sultan Abdul Rahman II had not been made with the consent of the Dutch and he was also clearly against colonial rule.[63]

The Dutch insisted that the sultan sign the agreement, but after consulting the fellow rulers of the state, Engku Kelana, Raja Ali, Raja Hitam and other members of the ruling elite, he refused, and decided to form a military regiment under the leadership of the prince regent, Tengku Umar. During a visit of the Dutch Resident's visit to Penyengat, the sultan then, on his own authority and without Dutch approval, summoned the rulers of Reteh, Gaung and Mandah, making the Resident feel as if he was being intimidated by the sultanate. The affiliates of the Roesidijah Klub, mainly the members of the administrative class, were thus able to slowly maneuver Abdul Rahman, once a supporter of Dutch rule, to act against the colonial power's wishes.[64]

On the morning of 11 February 1911, when the sultan and the court officials were in Daik to perform the Mandi Safar (a ritual purifying bath), ships of the Royal Netherlands Navy anchored in Penyengat Island and deployed hundreds of native soldiers (Dutch: marechausse) to lay siege to the royal court.[65] This was followed by the arrival of Dutch official K.M Voematra from Tanjung Pinang at the Roesidijah Club headquarters to announce the deposition of Abdul Rahman II.[66] The Dutch then seized the official coronation regalia,[67] and to prevent their seizure by the Dutch, many official buildings were deliberately razed by members of the court themselves. A mass exodus of civilians and officials to Johor and Singapore then took place.To avoid violence and the death of civilians in Pulau Penyengat, the sultan and his officials decided not to fight the Dutch troops. The sultan and Tengku Ampuan (the Queen) left Pulau Penyengat and sailed to Singapore in the royal vessel Sri Daik, while Crown Prince Raja Ali Kelana, Khalid Hitam and the resistance movement in Bukit Bahjah followed a couple of days later. The deposed Abdul Rahman II was forced to live in exile in Singapore, where he died there in 1930 and was buried in Keramat Bukit Kasita, Kampung Bahru Road.

The Dutch officially annexed the sultanate to avoid future claims from the monarchy. Dutch direct rule over the Riau Archipelago began in 1913, and the province was administered as part of the Residency of Riau and Dependencies (Dutch: Residentie Riouw en Onderhoorigheden). The Dutch Residency consisted of Tanjung Pinang, Lingga, the Riau mainland and Indragiri, while the Tudjuh Archipelago was administered separately as part of the Pulau-Tujuh Division (Dutch: Afdeeling Poelau-Toedjoeh).[68]

Japanese occupation and Independence

When World War II broke out, the Dutch initially seemed reluctant to defend their territories in the East Indies. This led the British to consider creating a buffer state in Riau. They discussed prospects for a restoration with Tengku Omar and Tengku Besar, descendants of the sultans, who were then based in Terengganu. However, as the war approached Southeast Asia, the Dutch actively engaged in the defensive system alongside the British, and the British decided to shelve the restoration plan.

In the aftermath of the war and the struggle against Dutch rule, several exile associations collectively known as the Gerakan Kesultanan Riau (Riau Sultanate Movement) emerged in Singapore, planning for a restoration. Some of the groups dated from as early as the dissolution of the sultanate, but started to gain momentum following the post-world war confusion and politics. From the ashes of political uncertainty and fragility in the East Indies following the World War II, a royalist faction known as the Association of the Indigenous Riau Malays (Malay: Persatoean Melayu Riouw Sedjati) (PMRS) emerged to call for the restoration of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The council was financially backed by rich Riau Malay émigrés and Chinese merchants who hoped to obtain tin concession. Initially founded in High Street, Singapore, the association moved to Tanjung Pinang, Riau with the unprecedented approval by the Dutch administrators. Based in Tanjung Pinang, the group managed to gain the consent of the Dutch for self-governance in the region with the foundation of the Riouw Council (Dutch: Riouw Raad, Malay: Dewan Riouw). The Riouw Council was the devolved national unicameral legislature of Riau, a position equivalent to a Parliament.[69]

After establishing itself in Tanjung Pinang, the group formed a new organisation known as Djawatan Koewasa Pengoeroes Rakjat Riow (The Council of Riau People Administration), with the members hailing from Tudjuh Archipelago, Great Karimun, Lingga and Singkep. This group strongly advocated the restoration of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate after the status of Indonesia became official. The leader of the council, Raja Abdullah, claimed that Riau Malays were neglected at the expense of the non-Riau Indonesians who dominated the upper ranks of the Riau civil administration. By restoring the monarch, they believed the position of Riau Malays would be guarded. The royalist association met with resistance from the republican group led by Dr. Iljas Datuk Batuah that sent delegates to Singapore to counter the propaganda of sultanate supporters. Based on Indonesian archive records, Dr. Iljas gained approvals from non-Malay newcomers to Riau, including Minang, Javanese, Palembang, and Batak people. He later formed a group known as the Badan Kedaulatan Indonesia Riouw (BKRI) (Indonesian Riau Sovereign Body) on 8 October 1945. The organisation sought to absorb the Riau Archipelago into the then-newly independent Indonesia, as the archipelago was still retained by the Dutch. BKRI hoped that the new administration under Sukarno would give the pribumis a fair chance to run the local government.

The royalist association would not give any public support to the Indonesian movement, as is evident in its refusal to display the Bendera Merah-Putih (Indonesian Flag) during the Indonesian Independence Day celebration on 17 August 1947 in Singapore. This led republicans to call the royalists 'pro-Dutch'. The royalists however, maintained that Riau was a Dutch territory and that only the Dutch could support it. The Dutch countered the claims of the BKRI by granting autonomous rule to the Riau Council, in which links with the Dutch would be maintained while a restored sultanate would play a secondary role. The council, created following the decree of the Governor General of the East Indies on 12 July 1947, was inaugurated on 4 August 1947, and represented a major step forward in the revival of the monarchy system. Several key members of the PMRS were elected to the Riau Council alongside their BKRI rivals, the Chinese kapitans from Tanjung Pinang and Pulau Tujuh, local Malay leaders of Lingga and Dutch Officials in Tanjung Pinang. On 23 January 1948, the states of the Bangka Council, the Belitung Council, and the Riau Council merged to form the Bangka Belitung and Riau Federation.[70]

The call for revival of the sultanate continued throughout the period of autonomous rule under the Riau Council, although the influence of republicanism also continued to strengthen. The appeal of revival began to subside following the dissolution of the Bangka Belitung and Riau Federation on 4 April 1950. After the official withdrawal by the Dutch in 1950, the Riau Archipelago became Keresidenan Riau under Central Sumatra Province following the absorption by the United States of Indonesia. Being one of the last territories merged into Indonesia, Riau was known as the daerah-daerah pulihan (recovered regions), and the Riau area became a province in August 1957.

The leader of Riau forces, Major Raja Muhammad Yunus, who led the bid to reestablish the sultanate apart from Indonesia fled into exile in Johor after his ill attempt.[71] The Geopolitical roots of the Riau Archipelago had molded her nationalist position to be sandwiched between the kindred monarchist Peninsular Malay Nationalism observed across the border in British Malaya with the pro-republic and pan-ethnic Indonesian Nationalism manifested in her own Dutch East Indies domain.

Contemporary era

After the war, from 1950 the Riau archipelago was a duty-free zone till the Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation in 1963. During this period, the Malaya and British Borneo dollar used in British Malaya was the principal currency in the region. Visa free movement of people, which existed then is now no more prevalent.[72] To affirm its fiscal stake in the region, a decree was passed on 15 October 1963 to replace the Malaya and British Borneo dollar (the circulating currency) with an Indonesian-issued currency, the Riau rupiah, which replaced the dollar at par. Although the rupiah resembled the Indonesian rupiah in appearance, it had a much higher value. Malayan money was withdrawn from 1 November 1963. The Riau rupiah was exchangeable as a foreign currency with the Indonesian rupiah. Since 1 July 1964, the Riau rupiah was no longer a valid currency, being replaced by the Indonesian rupiah at a rate of 1 Riau rupiah = 14.7 Indonesian rupiah.[73]

Due to its proximity to Singapore and Peninsular Malaysia, the Riau Islands area became the focus point during the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation. During this period, the territorial waters of the Riau Islands began to be visited by many Indonesian military forces who were members of the Indonesian Operations Command Corps or better known as the Indonesian Marine Corps. The city of Batam became one of the staging point of Indonesian troops during the confrontation, with the construction of military bases around the city.[74] Anti-Malaysian guerrillas were gathered at Tanjung Balai Karimun to be trained and then sent to Sambu Island for briefing before operation.[75] These guerrillas aimed to sabotage and spread information to help Indonesia fight the British in Malaysia, causing the economy around the Riau Islands, especially Tanjung Balai Karimun, does not function normally due to these military activities.[76] At that time, KOPASKA special forces of the Indonesian Navy infiltrated Singapore from military bases in the Riau Islands, around Batam, Tanjung Balai Asahan and the surrounding area. They usually use small boats with outboard motors and disguise themselves as local residents who usually have relatives on the Malay Peninsula and Singapore. The coastline of Batam and the surrounding islands were heavily fortified to deter possible British and Malaysian invasion.[77]

The end of the Indonesia-Singapore trade during the confrontation had made the economic conditions of the Riau Islands and Singaporeans disturbed. The inhabitants of Riau Islands can no longer barter or sell their produce to Singapore so that they cannot get basic necessities such as rice. Usually the basic needs of the Riau Islands population are brought in more from Singapore than anywhere else in Indonesia. Even vice versa, the supply of some needs of Singapore residents who are usually imported from the Riau Islands has been disrupted.[77] Hostilities ceased in 1966 after the 30 September Movement attempted a coup d'état, resulting in the overthrow of the Sukarno regime which leads to a peace agreement between Indonesia and Malaysia that was signed on 28 May 1966 at Bangkok, Thailand.[78]

In the 1970s, with the initial aim of making Batam a Singaporean version Indonesia, then according to Presidential Decree number 41 of 1973, Batam Island was designated as an industrial working area supported by the Batam Island Industrial Area Development Authority, better known as the Batam Authority Agency (BOB) as a driver of Batam's development. which is now the Batam Development Board (Indonesian: Badan Pengusahan Batam or BP Batam) . Along with the rapid development of Batam Island, in the 1980s, based on Government Regulation No. 34 of 1983, the Batam District which is part of the Riau Islands Regency was upgraded to Batam Municipality which has the duty to run government and community administration and support the development carried out by the Batam Authority (BP Batam).

Some level of unity returned in the Riau region for the first time after 150 years, with the creation of the Sijori Growth Triangle in 1989. But while bringing back some economical wealth to Riau, the Sijori Growth Triangle somewhat further broke the cultural unity within the islands. With Batam island receiving most of the industrial investments and dramatically developing into a regional industrial centre, it attracted hundreds of thousands of non-Malay Indonesian migrants, changing forever the demographic balance in the archipelago. A number of studies and books have detailed the growing violence and concern about identity and social change in the archipelago.[79][80] As the Malay, who were once the dominant ethnic group in the islands, have been reduced to about a third of the population, primarily as a result of immigration from elsewhere in Indonesia, they feel that their traditional rights are threatened. Similarly, the immigrants have felt politically and financially suppressed. Both of these causes have led to increased violence.[81] Piracy in the archipelago is also an issue.[82] There have been various attempts at both independence and autonomy for this part of Indonesia since the founding of Indonesia in 1945.[83]

Politics

Government

The province of Riau Island is led by a governor (gubernur) who is elected directly by the people. The Governor also acts as a representative or extension of the central government in the province, whose authority is regulated in Law No. 32 of 2004 and Government Regulation number 19 of 2010. The legislative branch of the Riau Island government is the Riau Islands Regional People's Representatives Assembly (Indonesian: Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Daerah Kepulauan Riau – DPRD Kepri), which is considered as a unicameral legislative body. Both governors and the members of the assembly are elected by citizens every five years by universal suffrage. Prior to this, the local executives had been elected by a vote of the assembly.[84] The governor office and the province assembly are located in Basuki Rahmat Road at Pulau Dompak, Tanjung Pinang.

The number of members of the assembly is at least thirty-five people and at most one hundred people with a term of office of five years and ends when the new assembly member takes an oath. Assembly membership was formalized by a decision of the Ministry of Home Affairs.[85] As of 2019, there are 45 seats in the assembly, scattered in several political parties. The majority (8 seats) are currently held by Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP) after the 2019 general election.[86]

Prior to Dutch colonization, most of the modern-day province of Riau Islands is part of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. The sultanate was headed by a Sultan.The Sultan, who was a Malay, acted as Head of State while the Dipertuan Muda/Yamtuan Muda (deputy ruler or Viceroy), a position held by the Bugis ruling elite, served as the Head of Government. The sultan's royal palace was located in Penyengat Inderasakti, while the Yang Dipertuan Muda resided in Daik, Lingga. After becoming a Dutch protectorate, a Dutch resident was installed as an adviser to the sultan. For the hereditary position of the Sultan, the sultan was fully subjected under the influence of the Dutch East Indies authority. Albeit he is de jure on the apex of the monarchy system, he is under the direct control of the Dutch Resident in Tanjung Pinang. All matters pertaining the administration of the sultanate including the appointment of the Sultan and the Yang Dipertuan Muda, must be made within the knowledge and even the consent of the Dutch Resident.

After the Dutch fully annexed the sultanate, a Dutch resident was posted in Tanjung Pinang, heading the Residency of Riau and Dependencies. During the 3 years of Japanese occupation, Japanese military officers and local Indonesian nationalist leaders headed the region.

Administrative Divisions

This province is divided into five regencies (kabupaten) and two autonomous cities (kota). These are subdivided into 70 districts (kecamatan) and then into 256 villages (desa or kelurahan). Each regency is headed by a regent (bupati), while each district is headed by a district chief (camat) and each village headed by a village chief (known as a kepala desa or penghulu) for each village in the district.[87]

During the Dutch East Indies era, the Riau Islands was included in the Residency of Riau and Dependencies (Dutch: Residentie Riouw en Onderhoorigheden), which is also based in Tanjung Pinang. The Dutch Residency consisted of Tanjung Pinang, Lingga, the Riau mainland and Indragiri, while the Tudjuh Archipelago was administered separately as part of the Pulau-Tujuh Division (Dutch: Afdeeling Poelau-Toedjoeh).[68]

The population of the regencies and cities of Riau Islands Province according to the 2015 census results and latest official projections.[1] Source: Badan Pusat Statistik, Republik Indonesia (web).

| Regencies and Cities | Capital | Districts | Area (km2) | Population Census 2015 | Population Estimate 2019 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Batam Kota, Batu Aji, Batu Ampar, Belakang Padang, Bengkong, Bulang, Galang, Lubuk Baja, Nongsa, agulung, Sekupang, Sungai Beduk | 1,595.0 | 1,184,978 | 1,420,624 | ||

| 2 | Bukit Bestari, Tanjungpinang Barat, Tanjungpinang Kota, Tanjungpinang Timur | 812.7 | 201,992 | 213,645 | ||

| 3 | Tarempa | Jemaja, Jemaja Timur, Palmatak, Siantan, Siantan Tengah, Siantan Selatan, Siantan Timur | 637.1 | 40,292 | 42,580 | |

| 4 | Teluk Bintan | Bintan Pesisir, Bintan Timur, Bintan Utara, Gunung Kijang, Mantang, Seri Kuala Lobam, Tambelan, Teluk Bintan, Teluk Sebong, Toapaya | 1,318.2 | 152,867 | 161,210 | |

| 5 | Tanjung Balai Karimun | Belat, Buru, Durai, Karimun, Kundur, Kundur Barat, Kundur Utara, Meral, Meral Barat, Moro, Tebing, Ungar | 920.64 | 225,113 | 234,624 | |

| 6 | Daik | Bakung Serumpun, Katang Bidare, Kepulauan Posek, Lingga, Lingga Utara, Lingga Timur, Singkep, Singkep Barat, Singkep Selatan, Singkep Pesisir, Senayang, Selayar, Temiang Pesisir | 2,205.95 | 88,617 | 90,085 | |

| 7 | Ranai | Bunguran Barat, Bunguran Batubi, Bunguran Selatan, Bunguran Tengah, Bunguran Timur, Bunguran Timur Laut, Bunguran Utara, Midai, Pulau Laut, Pulau Tiga, Pulau Tiga Barat, Serasan, Serasan Timur, Suak Midai, Subi | 2,008.8 | 74,454 | 78,802 | |

Environment

Geography and Climate

The total area of the Riau Islands is 10,595.41 km2 (4,090.91 sq miles), making it the 31st largest province in Indonesia, slightly smaller than the province of Banten in Java. 96% of the total area of the province is encompasses of ocean and only 4% of it is encompasses of land . The province shares maritime border with Vietnam and Cambodia to the north, the province of Bangka Belitung Islands and Jambi in the south, East Malaysia, Brunei and the province of West Kalimantan in the east and Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore and mainland Riau in the west.

The island of Batam, which lies within the central core group of islands (the Riau Archipelago), contains a majority of the province's population. Since becoming part of an economic zone with Singapore in 2006, it has experienced high population growth rates. Other highly populated islands in the Riau Archipelago include Bintan and Karimun, while the archipelago also includes islands such as Bulan and Kundur. There are around 3,200 islands in the province, which has its capital at Tanjung Pinang in the south of Bintan Island. The Riau Islands province includes the Lingga Islands to the south of the main Riau Archipelago, while to the northeast lies the Tudjuh Archipelago, between Borneo and mainland Malaysia; the Tudjuh Archipelago consists of four distinct groups – the Anambas Islands, Natuna Islands, Tambelan islands and Badas Islands — which were attached to the new province, though not geographically part of the Riau Archipelago. The 2015 census count was 1,968,313, less than estimated but it was still the second fastest growing province in Indonesia.

The highest point in Riau Islands is Mount Daik with a height of 1,165 meters (3,822 ft), which is located on Lingga Island.[88] Most of the area on Lingga Island is hilly. The Lingga area is generally in the form of an area with a fairly high slope, where there are as many as 76.92 percent of the area which has a slope of more than 15%, while the plain area (slope less than 2%) only encompasses of 3.49 ha or 3.14 percent of the total area.

With strategic geographical location (between South China Sea, Malacca Strait and Karimata Strait) and supported by an abundance of natural potential, Riau Islands could possibly become one of the economic growth centers for Indonesia in the future, especially now that in some areas of the Riau Islands (Batam, Bintan and Karimun), a pilot project for the development of a Special economic zone is being pursued through cooperation with the Singaporean government.[89] The implementation of the SEZ policy in Batam-Bintan-Karimun, is a close cooperation between the central government and local government, and the participation of the business world. This KEK/SER will be the nodes of the leading economic activity centers, supported by excellent service facilities and internationally competitive infrastructure capacity. Every business actor located within it will receive services and facilities of the highest quality that can compete with best practices from similar areas in Asia-Pacific.

As an archipelago, the climatic conditions in the province are affected by wind. Most of the province has wet tropical climate, there is rainy season and dry season interspersed with transition season with the lowest average temperature 20.4 °C. In November to February monsoon winds comes from the north and between June to December the monsoon winds comes from the south. During the northern monsoon the wind velocity at sea could range from 20–30 knots, on land the wind can range from 3–15 knots. This causes potentially extreme weather in the Riau Islands with rainfall of about 150–200 millimeters and wave height between 1.2 meters up to 3 meters. As in most other province of Indonesia, the Riau Islands has a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) bordering on a tropical monsoon climate. The climate is very much dictated by the surrounding sea and the prevailing wind system. It has high average temperature and high average rainfall. According to Köppen and Geiger, this climate is classified as Af. In the Riau Islands, the average annual temperature is 25.2 °C. Precipitation here averages 2607 mm.[90][91]

Oceanographic conditions, mainly wave and sea water current, in the study sites were influenced by wet monsoon period, i.e. from November to April. During the wet monsoon (wet season) the wind is characterized very strong, which blows from North-west to South-east or from South-west to North-east, with velocity ranges 7–20 knot (≈ 13–37 km/hour). The strongest wind usually occurs in around December–February, with velocity is about 45 km/hour.[92][93] During this season the sea wave may very high, sometime > 2 m especially during December–February. While the east monsoon (dry season), it usually occur in period of May to October, with wind velocity is relatively calm, that is about 7- 15 knot (≈ 13–28 km/hour). The sea wave was not very high reaching only around 0.8 m.[93][94] The sea water current in Riau islands follows the current pattern in Malacca strait. It is depends on the different between seawater level in northern part of Andaman Sea and southern part of Malacca Strait. Since seawater level in Pacific Ocean is always higher than in Indian Oceans, the seawater level in South China Sea is also higher than in Andaman Sea through out the year resulted in Malacca Strait there is a current, which flow to Northwest direction through out the year. In November to April, during the Northeast monsoon, Andaman Sea's current goes to the north. Therefore, majority of water masses are transported to the north. Consequent of this, during these months, Andaman Sea's water masses will be empty, and sea water level will be low or the different from South China Sea's sea water level will be higher. This sea water level reaches to maximum in February to March, while the different of sea water level between Northern and southern parts of Strait is about 50 cm, which resulted current velocity is about 12 cm/sec to Northwest.[93]

Conversely, during the southwest monsoon, May to October, most of the currents in western part of Andaman Sea go to east and south, therefore water masses will be gathering in Andaman Sea. This resulted in that sea water level increases in northern part of Malacca Strait, and the different of sea water level to South China Sea’s water level will be small, although in southern part of the Strait the sea water level is still higher. During this season, the water current in Malacca Strait flows to the north, with speed is little bit lower. Current velocity reaches to maximum in around July to August, with speed about 5 cm/sec. Oceanographic pattern is likely to affect the water quality and reef corals in the study sites. Strong wind during the wet monsoon period, for example, could cause water turbulence which affecting on high sediment, especially in coastal areas, and this might be worse with the high sediment run off from surrounding rivers and/or reclamation areas, such as happened in Batam. Water turbidity was recorded about 22 NTU during the wet season, and it is lower (about 7.4 NTU) in the dry season.[93][95]

Biodiversity

.jpg.webp)

Riau Islands became one of the coral reef conservation sites in Indonesia. Examples of coral reef conservation sites in the Riau Islands are Karang Alangkalam and Karang Bali. The area's marine life has made the Natuna Sea into a scuba diving destination. While there were once threats towards the coral reefs in the region, such as blast fishing, a survey by the Indonesian Institute of Sciences found that most of the coral reef ecosystems and mangrove forests in a number of locations in the waters around Batam are in a good condition.[96] Nevertheless, there are some threats that might endanger the ecosystem in the province, such as plastic waste which is mostly produced by households that are thrown into the sea.[97] Illegal fishing is also one of the factor that damages the ecosystem in the region.[98] The sea around the Natuna Islands in the previous years has been home to illegal fishing due to weak law enforcement in the region. Under the Widodo administration, the Natuna Sea has been frequently patrolled by the Indonesian Navy and the Indonesian Maritime Security Agency to prevent illegal fishing. This has resulted in the arrest of hundreds of fishing boats and their crews from countries such as Malaysia, Vietnam and China.[99][100][101]

As most of the Riau Islands consists of islands, many beaches can be found in the province, such as Lagoi Beach, Impian Beach, Trikora Beach, Nongsa Beach, Sakerah Beach, Loola Beach, Padang Melang Beach, Nusantara Beach, Batu Leafy Beach, Indah Beach, Tanjung Siambang Beach, Tanjung Beach, Melur Beach, Melayu Beach, Pelawan Beach, Sisi Beach and Cemaga Beach.

The wealth of flora and fauna in the Riau Islands is also very diverse. The Lutjanus gibbus and Piper betle are the fauna and flora symbol of the Riau Islands province respectively.[102] The Humphead wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus), which is an endangered type of fish, inhabits the Natuna Sea in the northern part of the province. In addition, Dugongs also live in the waters around the island of Bintan. Some other rare animals are the Tarsius, and the Natuna Island surili (Presbytis natunae), native to the island of Natuna. The Natuna Island surili is one of the 25 most endangered primates on Earth.[103] Wealth of flora in the province includes the Oncosperma tigillarium, dragon fruit, areca nut and the rare udumbara plants that live on the Engku Puteri Plateau, Batam Center. The Riau Islands has 2 nature reserves, namely Pulau Burung Nature Reserve and Pulau Laut Nature Reserve.

Economy

Riau Islands GDP share by sector (2017)[104]

The geographical position of the Riau Islands, which is close to neighboring countries located near the Strait of Malacca, which is one of the busiest shipping lane in the world, is also a major factor in the need to increase competitiveness. The geographical location can be a leverage in attracting foreign and domestic investors. However, the strategic geographical location will not provide benefits if the Riau Islands do not have competitiveness. This is because skilled workers and investors are more interested in areas that have competitiveness than regions that are not competitive. Therefore, increasing competitiveness is a necessity to attract investors, both foreign and domestic, to invest in the economic development of the Riau Islands.[105]

The economic growth rate of Riau Islands Province in 2005 was 6.57%.[106] Sectors that grew well (faster than the total GRDP growth) in 2005 included the transportation and communication sector (8.51%), the manufacturing sector (7.41%), the financial sector, leasing, and corporate services (6.89%), the service sector (6.77%), and the trade, hotel and restaurant sector (6.69%). GRDP Per capita of the Riau Islands in the last five years (2001–2005) tends to increase. In 2001 the GRDP per capita (above the prevailing price – without oil and gas) was Rp. 22,808 million, and in 2005 it increased to Rp.29,348 million. But in real terms (without calculating inflation) the Per capita GRDP (without gas) in 2001 was only Rp.20,397 million, and in 2005 it increased to Rp. 22,418 million.[106]

The potential of natural wealth in the Riau Islands comes from mining and the manufacturing industries. The manufacturing sector contributes more than 35% and the processing industry accounts for 15.26% of the economy in Riau Islands with oil and gas commodities. In addition to the mining sector, community economic activities are dominant in the agriculture, plantation and forestry sectors. Riau Islands economic growth continued to decline in the period 2011–2014, then increased in 2014. During the period 2011–2014, the economic performance of the Riau Islands had an average growth rate of 6.31%.[105]

In 2017, the manufacturing sector formed the largest GDP per share in the province, forming around 36.8% of the total GDP per share of the province.[107] Based on the main commodities, mineral fuels, machinery and electrical equipment remain the mainstay trade of the Riau Islands. This type of commodity has not changed significantly compared to previous years. This needs to be considered given the expansion of the market must also be accompanied by an expansion of commodities both in quality and type.[106]

The second largest sector is the Construction industry, forming around 18% of the total GDP sector.[107] The development of the number of construction businesses in the Riau Islands fluctuated considerably during the period 2008–2010. In 2010 the number of construction companies in the province was 1,570, with the value of construction completed (revenue) of Rp 5,483 billion. Number of National Labor Force Survey Results show that the number of residents working in the construction sector has fluctuated from time to time. As many as 43,232 people were recorded in February 2009, then decreased in February 2010 to 29,932 people, again increased in August 2010 to 50,833 people, then decreased in February 2011 to 58,211 and again increased in August 2011 to 59,755 people. Because the Riau Islands is a new developing province and almost half of the existing human resources come from outside the Riau Islands, this has caused housing needs in the Riau Islands to be out of proportion to their availability. This condition also seems to have caused housing costs to rise in the Riau Islands relatively faster than in other regions. The results of the National Socio-Economic Survey show that on average the expenditure per capita of the population for rental costs/housing contracts is the highest type of expenditure for non-food commodities, and the figure tends to increase every year. This fact is in line with the increasing frequency of commodity rental prices in the Riau Islands.[106]

The third largest sector is the mining industry.[107] Riau Islands is the largest bauxite producing region in Indonesia. This can be seen from the number of bauxite mining companies. Since 2008, the number of bauxite mining companies has always been the highest compared to other mining companies, although the number has always dropped from 2008 to 2010. In 2009 the number of bauxite companies fell by 37 companies to 32 in 2010. This decline also had an impact on the decline in the number of workers and output produced by this sector. The tin company is the second largest company in the Riau Islands after bauxite. Tin companies also have the same situation as bauxite companies that are experiencing a decline. The tin company which initially had 25 companies in 2009 decreased to 22 companies in 2010.[106]

A small but significant sector in the province is the agriculture sector, forming around 3.5% of the total GDP sector.[107] Despite having limited agricultural land, and production of food crops (mainly rice), the Riau Islands have not been able to meet the needs food for its population. This problem is caused by rice productivity that is still low. Cassava plants have the highest productivity, then sweet potato and rice plants are ranked third. In 2011, rice productivity in the Riau Islands reached 3.16 tons per hectare, far below the productivity of cassava and sweet potatoes, which amounted to 10.83 tons per hectare and 7.75 tons per hectare, respectively. When viewed from the harvested area and rice production in 2011, it experienced a very small increase as well as productivity. Rice productivity in 2010 was 3.15 tons per hectare, cassava was 10.82 tons per hectare and sweet potatoes was 7.72 tons per hectare. The increase in productivity of rice and cassava was only 0.01 tons per hectare and sweet potatoes was 0.03 tons per hectare. Corn and peanut crops are food crops in Riau Islands with low productivity during 2010–2011. Whereas for corn productivity in 2010 amounted to 2.13 tons per hectare decreased to 2.12 tons per hectare in 2011. While for peanuts the productivity remained, at 0.92 tons per hectare. Decrease in corn productivity is due to the harvested area for maize also has decreased, besides it is also the effect of pests that cause disruption of corn pests.[106] Plantation and horticultural crops are types of plants that are quite potential to be cultivated in Riau Islands. This is based on the high price of agricultural products produced by these two types of businesses. As shown by the NTP (Farmer Exchange Rate) data, only estate and horticultural farmers have almost certainly an index value above 100. This condition is of course caused by the still higher price of goods produced by farmers compared to the price of goods needed, both for consumption and the cost of production. Production of rubber plants in 2011 experienced a very high increase of 118 percent. While coconut plants experienced a very small increase of 2.4 percent. As for fruit production, in 2011, only jackfruit and banana increased, where jackfruit production increased by 5 percent and banana production increased by 50 percent, compared to production in 2010. As for the production of pineapple, durian, orange and rambutan decreased in 2011.[106]

The island of Natuna located in the north-eastern part of the province is home to the largest natural gas field in Indonesia (estimated to 1.3 billion m3). The field was discovered in 1973 by Agip.[108][109] In 1980, the Indonesian state-owned oil company Pertamina and Exxon formed a joint venture to develop Natuna D-Alpha. However, due to the high CO

2 content the partnership was not able to start production.[110] In 1995, the Indonesian government signed a contract with Exxon but in 2007, the contract was terminated.[110][111] In 2008, the block was awarded to Pertamina.[108] The new agreement was signed between Pertamina and ExxonMobil in 2010. Correspondingly, the field was renamed East Natuna to be geographically more precise.[112] In 2011, the principal of agreement was signed between Pertamina, ExxonMobil, Total S.A. and Petronas.[113][114] In 2012, Petronas was replaced by PTT Exploration and Production.[113][115] As of 2016, negotiations about the new principal of agreement have not finalized and consequently, a production sharing contract is not signed.[116] The area around the gas field is currently disputed between Indonesia and China.[117]

Infrastructure

From 2016 until 2020, the central government has outlined more development plan for the province. In 2017, the Indonesian Ministry of Public Works and People's Housing has allocated around Rp. 500 million (US$36 million) for the development of infrastructure in the Riau Islands, which includes building new infrastructure as well as improving existing infrastructure in the province.[118] Meanwhile, in 2019, the Riau islands provincial government has also allocated a budget of around Rp. 15,5 trillion (US$1 billion) that is allocated from the province's Regional Revenue and Expenditures Budget.[119] This is an increase from 2018's annual budget, which is around Rp. 13,9 trillion (US$980 million).[119] The government continues to work towards accelerating maritime development (both economy and tourism) in Indonesia's foremost and outermost regions, one of which is in the Riau Islands province to support economic development, tourism, and marine resources in the Riau Islands.[120]

Energy and water resources

Electricity distribution in the state are operated and managed by the Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN). According to the Indonesian Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, as of 2017, there are 240 power plants in the Riau Islands, consisting of 2 steam power plant, 1 Solar power plant and 237 diesel power plant.[121] Currently, the largest power plant in the Riau Islands is the Tanjung Kasam power plant in Batam, which has a capacity of 430 MW. It started operating in 2012.[122] The power plant supplies around 25% of the total electric needs in Batam and the surrounding region.[123] As of 2017, there are still around 104 villages in the province that is not fully electrified yet.[124] In response, PLN has allocated around Rp. 751 billion (US$5.3 million) to build new power plants in the province with a total capacity of 45.500 KW. The location of the power plants will be scattered at several points such as in Natuna Regency.[125] It also aimed that by 2020, all villages in the Riau Islands will be fully electrified.[126]

All pipes water supply in the province is managed by the Riau Islands Municipal Waterworks (Indonesian: Perusahaan Daerah Air Minum Kepulauan Riau – PDAM Kepri). Reliable water supply is one of the main problem faced by the people of the Riau Islands. The province has often faced a shortage in clean water, mostly due to drought during the dry seasons.[127][128][129] In response, the Indonesian government is currently constructing several dams across the province to anticipate water shortage in the future. Examples of dams that are being constructed are the Sei Gong Dam in Galang Islands, Batam, which as a capacity of 11,8 million m3 of water. Construction of the dam has finished in 2018 and is predicted to begin operation in 2019.[130] Another dam that is also under construction is the Sei Busung Dam in Bintan. It is slated to begin operation 2021 and would have a water capacity of 100 million m3 .[131]

Internet and telecommunication

In 2018, the household internet broadband penetration in the Riau Islands is 70%, which is above the Indonesian national figure around 54.86%, according to the survey results from the Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association (Indonesian: Asosiasi Penyelenggara Jasa Internet Indonesia) (APJII).[132][133] Nonetheless, there are still many regions in the Riau Islands that has limited or no internet access, especially around the outlying regions of Anambas and Natuna Islands.[134] Efforts have been taken by the government to improve internet access in the region, such as the construction of the Palapa ring, which is a massive, nationwide internet network using fiber-optic wires that will provide high-speed internet connection throughout the nation. The project aimed to make all the capital cities of regencies and municipalities in Indonesia connected with broadband or high-speed internet infrastructure. The idea was preceded by the difficulties of the outermost, rural, and disadvantaged regions in Indonesia in obtaining adequate telecommunications access.[135] The project work process began in 2017. Currently Palapa Ring construction has been completed and has also been inaugurated. A number of Indonesian telecommunications operators have begun cooperating with the Indonesian Ministry of Communication and Information Technology so that the internet network can be accessed smoothly. The Palapa Ring network was completed in late 2019 and was inaugurated by the Indonesian president Joko Widodo on 14 October 2019.[136]

Presently, the mobile telecommunication penetration in the outlying regions of the Riau Islands such as Natuna and Anambas are increasing due to the improvement of telecommunication infrastructure compared to the previous years. Several Indonesian network providers such as XL Axiata and Telkom Indonesia has started building more BTS tower around the region to increase network coverage around the region. XL Axiata has been present in Anambas and Natuna since 2008 with 2G services that use satellite connections and then upgraded to 3G services. In March 2019, XL Axiata inaugurated the 4G data network in the Anambas Islands, by using the West Palapa Ring backbone, in collaboration with the Telecommunications and Information Accessibility Agency (BAKTI) in using the West Palapa Ring network.[137] While in 2018, Telkomsel strengthens 4G services in Natuna Regency and Anambas Islands Regency by building two new 4G base transceiver stations. With the deployment of 4G network infrastructure in the country's border areas, Telkomsel now operates 89 BTS tower in Natuna and Anambas, including eight 4G BTS tower.[138]

Land

As most of the Riau Islands consists of oceans and outlying islands, land transportation is only limited to the larger islands in the province, such as Batam and Bintan. As of 2014, there are 4,954 km (3078 mi) of connected roadways in the Riau Islands, with 334 km (208 mi) being national highways, 512 km (318 mi) being provincial highways and the rest being city/regency highways.[139] Most of the main roads in the Riau Islands has been paved, but there are still road sections that remain unpaved, especially in the outlying regions. Despite this, efforts has been taken by the government to improve road infrastructure in the regions, such as building more roads and improve existing roads, as well as building new bridges to connect river and islands in the province.[140]

As in other provinces in Indonesia, the Riau Islands uses a dual carriageway with the left-hand traffic rule, and major cities in the province such as Batam and Tanjung Pinang provide public transportation services such as buses and taxis along with Gojek and Grab services. The Tengku Fisabilillah Bridge which connects Batam and Tonton Island is currently the longest bridge in the Riau Islands. It stretches for 642 meters and is a cable-stayed bridge with two 118 m high pylons and main span 350 m.[141] The bridge is part of the Barelang Bridge, a chain of 6 Bridges of various types that connect the islands of Batam, Rempang, and Galang, Riau Islands that was constructed in 1992 and finished in 1997 and was inaugurated by former Indonesian president B. J. Habibie, who oversaw the project in construction, aiming to transform the Rempang and Galang islands into industrial sites (resembling present-day Batam).[142][143] Travelling from the first bridge to the last is about 50 km and takes about 50 minutes. Over time the bridge sites have grown more into a tourist attraction rather than a transportation route.[144] The Tengku Fisabilillah Bridge will be surpassed as the longest bridge in the province by the Batam-Bintan bridge, which is still under the planning stage. Construction is expected to start in 2020 and finish in 3 to 4 years time. The Batam-Bintan bridge will have a length of around 7 km (4 mi).[140][145][146]

Presently, there is no toll road in the Riau Islands. However, the government has announced a plan to build a new toll road in Batam which would connect Hang Nadim International Airport in the eastern part of the island and the Batu Ampar area in the northern part. The toll road will have a length of 19 km (12 mi) and will be constructed with various construction methods. About 5.2 kilometers of the toll road will elevated while the rest will be at grade.[147][148]

Air

The province is served by several airports, the largest being Hang Nadim International Airport in Batam. Originally developed to handle diversions of aircraft from Singapore Changi Airport in case of an emergency, it has sufficient facilities for wide-body aircraft such as Boeing 747s. The airport has the longest runway in Indonesia and the second longest runway in Southeast Asia, after Kuala Lumpur International Airport, at 4,214 metres (13,825 ft) long. The airport serve flights to major Indonesian cities such as Jakarta, Medan, Surabaya and Palembang, as well as some international destinations such as Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia and cities in China such as Shenzhen and Xi'an. Due to its proximity to Singapore, many people who is travelling abroad usually choose to go to Changi Airport in Singapore since it serves more destinations to other countries compared to Hang Nadim International Airport or Soekarno–Hatta International Airport in Jakarta.

The second-largest airport in the province is the Raja Haji Fisabilillah International Airport in Bintan. It mostly serves flight to Jakarta and destinations within the province such as Batam and Natuna. Other airports in the province are the Dabo Airport in Singkep, Raja Haji Abdullah Airport in Karimun, Letung Airport and Matak Airport in the Anambas Islands and Raden Sadjad Airport in the Natuna Islands. Raden Sadjad Airport is currently being developed as a military airbase due to territory dispute between Indonesia and China on the waters off the coast of the Natuna Islands. Additional facilities, such as aircraft hangars, ILS, refueling hangar are also currently being added.[149]

As the closest neighbour of Singapore and to realise that Soekarno–Hatta International Airport is fully used, Lion Air is developing hangars in Batam Island and Garuda Indonesia is developing a new airport, with runway and maintenance facilities so as to make a new air hub in Bintan Island.[150]

Sea

Due to the fact that the Riau Islands is an archipelago province located in an archipelago country, water transport becomes the main type of transportation. Inter-island connections are often contacted by water transport. This type of water transport includes ferries, canoes, speedboats, freight boats, etc. This ships consists of a ship operated by the state-owned Pelni company as well as private vessels. The main ports are located in Batam and Bintan. There largest cargo port is the Port of Batu Ampar in Batam. It serves cargo ships to and from Batam and has a capacity of 1000 container.[151]

Major cities such as Batam and Tanjung Pinang serves international ferry routes to Singapore and Malaysia. Ferries connect Batam to Singapore, Bintan, and Johor Bahru (Malaysia). Five ferry terminals are on Batam: Batam Harbour Bay Ferry Terminal, Nongsapura Ferry Terminal, Sekupang, Waterfront City, and Batam Center Ferry Terminal. Connections to Singapore are by way of Harbourfront and Tanah Merah Ferry Terminals run by Singapore Cruise Centre (SCC). While in Tanjung Pinang, the Sri Bintan Pura Harbour is the largest harbour in Bintan. This port connects the city of Tanjung Pinang with ports to the north (Lobam port and Bulang Linggi port), with islands to the west, such as Tanjung Balai Karimun, Batam, and islands to the south such as Lingga and Singkep islands. For international ferry services, the port of Sri Bintan Pura also has transportation links to Singapore (HarbourFront and Tanah Merah) and Malaysia (Stulang Laut).

Healthcare

Health-related matters in the Riau Islands is administered by the Riau Islands Health Agency (Indonesian: Dinas Kesehatan Provinsi Kepulauan Riau).[152] According to the Riau Islands branch of the Indonesian Central Agency on Statistics, as of 2016, there are around 28 hospitals in the Riau Islands which consists of 13 state-owned hospitals and 15 private hospitals.[153] According to the Riau Islands provincial government, there are 87 clinics in Riau Islands as of 2018, of which 70 of them are already accredited, while the remaining 17 clinics are not yet accredited.[154] The number of hospitals and clinics in the Riau Islands are still far below the ideal level, according to the Ombudsman of the Republic of Indonesia.[155]

The most prominent hospital is the Riau Islands Regional General Hospital (Indonesian: Rumah Sakit Umum Daerah Kepulauan Riau) in Tanjung Pinang, which is the largest state-owned hospital in the province.[156] Other prominent hospital in the province is the Santa Elisabeth Hospital in Batam and the Embung Fatimah Regional General Hospital which is also located in Batam. Due to lack of adequate health facilities in the province, many people usually travel to neighboring countries such as Malaysia and Singapore to get medical treatment as these countries has better medical infrastructure compared to the Riau Islands.

Education

Main articles: List of universities in Indonesia

Education in the Riau Islands, as well as Indonesia in a whole, falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and Culture (Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan or Kemdikbud) and the Ministry of Religious Affairs (Kementerian Agama or Kemenag). In Indonesia, all citizens must undertake twelve years of compulsory education which consists of six years at elementary level and three each at middle and high school levels. Islamic schools are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Religious Affairs. The Constitution also notes that there are two types of education in Indonesia: formal and non-formal. Formal education is further divided into three levels: primary, secondary and tertiary education. Indonesians are required to attend 12 years of school, which consists of three years of primary school, three years of secondary school and three years of high school.[157]

As of 2019, there are 1,621 schools in the Riau Islands, which consists of 1,051 government-owned schools and 570 private schools.[158] There are several international schools in the Riau Islands, which are mostly located in Batam and the surrounding area, due to its significant expatriate populations, such as Sekolah Global Indo-Asia,[159] independent school Batam,[160] Australian Intercultural School,[161] Sekolah Djuwita Batam,[162] etc. Most of the teachers that worked in these international schools are English-educated teachers from Singapore, Malaysia, United Kingdom, Australia, United States and Philippines.

There are around 40 universities in the Riau islands, both public and private universities. Public universities in the Riau Islands falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Research and Technology (Kementerian Riset dan Teknolog) or the Ministry of Religious Affairs for Islamic universities. Notable public universities in the province is the Raja Ali Haji Maritime University and the Sultan Abdurrahman Islamic College in Tanjung Pinang, and the Batam State Polytechnic in Batam.[163][164] There are at least one international university in the Riau Islands, which is the Batam International University located in Batam.

Demographics

According to the national census released in 2017 by the Indonesian Central Agency on Statistics, Riau Island has a population of 2,082,694 people, spread throughout 6 regencies and 2 cities, consisting of 952,106 males and 909,267 females.[165][166][167] This makes the Riau Islands the 26th most populated province in Indonesia.[168] The population in the province is predicted to increase to 2,768,000 by 2030.[169] In 2015, the population density in the Riau Islands is 241 people per km2 .[170] The city of Batam is the most populated administrative divisions in the province, with a number of 1,283,196 people, while the Anambas Islands Regency is the least populated administrative divisions in the province, with just a number of 76,192 people.[165] Most of the population of Riau Island is concentrated on the island nearest to Singapore, such as Batam and Bintan.

Ethnicity

Riau Islands is a very diverse and multi-ethnic province. Owing to its proximity to Singapore, many people from other parts of Indonesia has migrated to the province. As of 2009, the ethnic groups in Riau Island consist of Malays (35.60%), Javanese (18.20%), Chinese (14.3%), Minangkabau (9.3%), Batak (8.1%), Buginese (2.2%) and Banjarese (0.7%).[172]

The Malays are the largest ethnic group with a composition of 35.60% of the entire population of the Riau Islands. They are the native people of the Riau Archipelago. From the ancient times, the Riau Archipelago is considered the hub of Malay cultures. In the past, several Malay kingdoms and sultanates existed in the archipelago, the most notably being the Riau-Lingga Sultanate. A major sub-group of the Malay inhabiting the province is the Orang laut (sea people). The Orang laut are Malays who are Nomadic in nature and have a rich marine culture. Presently, many Orang laut have settled in coastal areas of the province. The Orang laut are encompasses of numerous tribes and groups inhabiting the islands and estuaries in the Riau-Lingga Archipelagos, the Tudjuh Archipelago, the Batam Archipelago, and the coasts and offshore islands of eastern Sumatra, southern Malaysia Peninsula and Singapore.[173] The geographical condition of the Riau Islands, which has almost 99% of its area as water, has made quite a number of Orang Laut groups living in this area. In the Riau Islands, the Orang laut are usually found in islands and river mouths.[174] The Orang laut are boat-dwelling tribe with main livelihoods as fish finders and other marine animals, such as tripang (sea cucumber). This subsystem economic model is the characteristic of their culture. Since the implementation of the policy of relocation of settlements by the Indonesian Government in the late 1980s to the early 1990s, the customs of the Orang laut are gradually disappearing.[175][176]

_en_Tek_Hwa_Seng_bij_Poeloe_Samboe_TMnr_10010680.jpg.webp)

Other ethnic group are mostly immigrants coming from different parts of Indonesia. Due to its proximity from Singapore, Riau Islands have become a melting pot for different ethnic groups coming from other parts of Indonesia. The Javanese is the dominant ethnic group of the immigrants, forming 18.2% of the total population. The Javanese who stayed here are mostly due to the Transmigration program enacted by the Dutch during the colonial period to reduce the overpopulated Java and continued until the end of the New Order. Another notable immigrants are the Minangkabau (Minang), who mostly originated from West Sumatra. Owing to its rantau (migration) culture, many Minangkabau people has migrated away from their homeland.The history of the Minangkabau migration in West Sumatra to the Riau mainland and the Riau Islands has been recorded to have lasted a very long time. When the means of transportation were still using the river, many Minang people migrated to various cities such as Tanjung Pinang and Batam.[177] Other ethnic groups, such as the Batak from North Sumatra, the Banjarese from South Kalimantan and the Buginese from South Sulawesi also inhabit the province, albeit to a lesser extent.