The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel

The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel is a landmark building at 200 S. Broad Street at the corner of Walnut Street in Center City, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania United States. Constructed in 1904 and expanded to its present size in 1912, it has continued as a well-known institution for more than a century and is still widely known by that original, historic name. In 1988 the building was converted to a mixed-use development. It has been known since then as The Bellevue. The hotel portion is currently managed by Hyatt as The Bellevue Hotel.

| The Bellevue | |

|---|---|

Bellevue Stratford Hotel | |

(1976) | |

| |

| Coordinates | |

| Built | 1902–04 |

| Architect | G. W. & W. D. Hewitt Hewitt & Paist |

| Architectural style | French Renaissance |

| NRHP reference No. | 77001182[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 24, 1977 |

| |

| Former names | Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, Fairmont Hotel, The Westin Bellevue-Stratford, Hotel Atop the Bellevue, Park Hyatt Philadelphia at the Bellevue, Hyatt at the Bellevue |

| Alternative names | Bellevue-Stratford Hotel |

| General information | |

| Address | 200 S. Broad Street |

| Town or city | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Country | United States

Building details |

| |

| Hotel chain | Hyatt |

History

George Boldt

Born Georg Karl Boldt in Prussia in 1851, he immigrated to the United States as a teenager in 1864. Beginning as a kitchen worker, at age 25 was hired by William Kehrer, steward of The Philadelphia Club, as his assistant steward at the time of the 1876 Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia. Soon after he married his employer's daughter, Philadelphia-born Louise Kehrer. Prominent members of the Philadelphia Club assisted the couple in setting up their own hotel, the Bellevue, at the northwest corner of Broad and Walnut Streets, in 1881. A small hotel, it quickly became nationally known for its high standard of service, elite clientele, and fine cuisine; it is believed that Chicken à la King was created in the 1890s by hotel cook William "Bill" King.

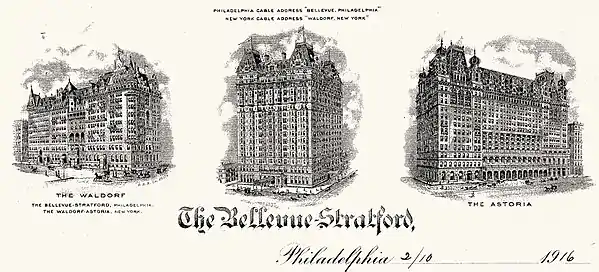

In 1890, George Boldt was invited by William Waldorf Astor to be proprietor of the new Waldorf Hotel in New York City. Louise Boldt had been instrumental in making their Philadelphia hotel attractive and socially acceptable to wealthy women. This was probably a major motivation for Astor in asking George Boldt to become proprietor of his new Waldorf, later expanded by John Jacob Astor IV to become the world-class institution known as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Construction

With his success at managing the enormous Waldorf Astoria, George Boldt decided to build a similarly large and luxurious hotel in his home town. He acquired the Stratford Hotel across Walnut on the southwest corner and commissioned the grand 19 floor Bellevue-Stratford Hotel, designed in the French Renaissance style by G.W. & W.D. Hewitt, with Purdy and Henderson, Engineers. These Philadelphia architects also designed the Boldts' famous landmark residence, Boldt Castle in the Thousand Islands. Opening in 1904 after two years in the making and costing over $8,000,000 (in 1904 dollars), the Bellevue-Stratford was described at the time as the most luxurious hotel in the nation and perhaps the most spectacular hotel building in the world. It had hundreds of guest suites in a variety of styles, the most magnificent ballroom in the United States, delicate lighting fixtures designed by Thomas Edison, stained and leaded glass embellishments in the form of transoms and Venetian windows and sky-lights by Alfred Godwin, and the most celebrated marble and hand-worked iron elliptical staircase in the city. In 1912 a large extension to the west brought it up to a reputed 1,090 guest rooms, and added the top floor domed function rooms.

Early years

From its beginning, the Bellevue-Stratford was the center of Philadelphia's cultural, social and business activities. It soon functioned as a sort of clubhouse for the Philadelphia establishment, not only a place where the rich and powerful dined and occasionally slept, but also the venue for their meetings and social functions. Charity balls, society weddings, club meetings and special family gatherings have all been held in the hotel's ballrooms and meeting rooms. The rich and famous, royalty and heads of state from all over the world, presidents, politicians, actors and famous writers have stayed within its walls. 15 U.S. Presidents, beginning with Theodore Roosevelt and ending with Ronald Reagan, have been guests at the hotel, which is respectfully called the "Grand Dame of Broad Street."

Originally the western end of the building was only three stories high. In 1911 Boldt added extensions to the hotel and carried it to the full nineteen stories. It was completed in 1912 at a cost of $850,000.

In June 1919 the Bellevue was leased to T. Coleman du Pont, together with Lucius M. Boomer, president of Boomer-du Pont Properties Corporation. The ground and building were retained by George C. Boldt Jr. Boomer-du Pont offered the Boldt family $7,500,000 for the hotel. They refused, as the asking price was $10,000,000. In June 1925 the company backed by duPont, The Bellevue Company purchased the hotel for $6,500,000 from the heirs of George C. Boldt. It was said that $3,000,000 was paid in cash and a mortgage was taken over the property for $3,500,000.

In October 1926, Queen Marie of Romania[2] stayed at the hotel. The Royal Suite of 11 rooms on the seventh floor to be occupied by Queen Marie and her entourage of 19 has a history. Among the world-famous people who have occupied the suite are President and Mrs. Calvin Coolidge, Cardinal Mercier of Belgium, President and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, Marshal Joffre, General John J. Pershing, President and Mrs. Warren G. Harding, a brother of the Emperor of Japan, Sir Esme Howard, Ambassador Jules Jusserand, and Ambassador Auckland Geddes.

During the 1920s through the 1940s, the noted global host Claude H. Bennett managed the now 735 room Philadelphia hotel. His son, Robert C. Bennett (Cornell Hotel School 1940), and grandson, Robert Jr. (Drexel Hill, PA), Professor of Hotel Management at a suburban Philadelphia community college (Delaware County Community College), were both on the senior management staff of the "Grand Dame" of Broad Street as late as the 1970s prior to the temporary hotel closing.

Decline

The Great Depression brought hard times to the Bellevue-Stratford, although it continued to be "Philadelphia's hotel." Gradually, through lack of income and attention, the hotel's glitter began to tarnish. During the 1940s and 1950s, the classic architecture and rich decorative details of the hotel were thought to be overpowering, anachronistic and even offensive.[3]

Noted hotelier Charles Todd managed the hotel after this period, bringing it back "into the black." He had managed the Lake Placid facility for the 1932 Winter Olympics, and later retired from the famed Hotel Hershey in Hershey, Pennsylvania in the 1960s.[4] He is also known for teaching a public domain game called "The Landlords Game" (teaching economic principles espoused by the Henry George School of Economics in Philadelphia) in the 1930s to Charles Darrow, who later claimed to have invented it as Monopoly.[5]

The Bellevue-Stratford was the headquarters of the 1936 and 1948 National Conventions of the U.S. Republican Party and the 1948 Convention of the Democratic Party.

On October 30, 1963, the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel became a 'testing ground' of sorts for the 35th U.S. President, John F. Kennedy, as he successfully rode in a 13-mile open car motorcade from the Philadelphia International Airport to the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel.[6] Less than a month later, JFK was assassinated in an open car motorcade through the city of Dallas, Texas.

The hotel gained worldwide notoriety in July 1976, when it hosted a statewide convention of the American Legion. Soon after, a pneumonia-like disease killed 29 people and sickened 182 more who had been in the hotel.[7] The vast majority were members of the convention. The negative publicity associated with what became known as "Legionnaires' Disease" caused occupancy at the Bellevue-Stratford to plummet to 4 percent[8] and the hotel finally closed on November 18, 1976.[8]

In 1977, Dr. Joseph McDade discovered a new bacterium, which was identified as the causative organism. It thrives in hot, damp places like the water of the cooling towers for the Bellevue-Stratford's air-conditioning system, which spread the disease throughout the hotel.[9] The bacterium was named Legionella and the disease, legionellosis, after the first victims.

The empty building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1977.

Restoration

The Bellevue-Stratford was sold in June 1978 to the Richard I. Rubin Company for $8.25 million.[10] Rubin undertook a $25-million restoration. The guest rooms were completely gutted and their number reduced from 725 to 565, while the public areas were painstakingly restored to their 1904 appearance. 44,000 square yards of carpet were imported from Ireland, 25 tons of marble came from Portugal and crystal chandeliers were sourced from Uruguay.[10]

The hotel reopened on September 26, 1979,[11] managed by Fairmont Hotels, as the Fairmont Hotel. The following year, Western International Hotels bought a 49-percent interest in the hotel and assumed management on November 15, 1980.[12] They returned the hotel to its original name, Bellevue Stratford, and announced plans to construct a huge parking garage adjacent to the hotel. Two months later, Western International was itself renamed Westin Hotels, and the hotel was soon renamed The Westin Bellevue Stratford. By the mid-1980s, the hotel was struggling to fill its hundreds of rooms. Philadelphia had lower hotel occupancy rates than other major East Coast cities at the time, and a lengthy conflict between city and state officials[8] over financing for a new convention center, which would eventually open in 1993, meant that demand for hotel rooms in Center City was even lower than expected.[10] With an occupancy rate of 55 percent, far below the 65-70 percent necessary to break even,[8] and having operated at a total cash loss[13] of $25 million from 1979–1985,[14] never once turning a profit since its restoration,[10] the hotel's owners announced in January 1986 that it would close on February 2.[8] A lawsuit by the union representing the hotel's 450+ employees[15] over the short notice given to its members, resulted in an agreement to keep the hotel open until April 2,[14] but with The Westin Bellevue Stratford's advance bookings transferred to other hotels as a result of the closure announcement,[15] only two floors of guest rooms still in use,[16] and only 10 to 15 guests a night in the enormous building by that point, the union accepted a settlement of $500,000 and a promise that the renovated hotel would remain a union shop and agreed to an earlier closing date.[14] The Westin Bellevue Stratford closed on March 7, 1986.[14]

Mixed-use conversion

The Rubin Company bought out Westin's stake in the hotel[8] and again undertook extensive work on the building, at a cost of $100 million, designed by architects from RTKL Associates Inc. in Baltimore and the Vitetta Group-Studio Four of Philadelphia.[17] The building's name was shortened to The Bellevue. The grand public areas on the ground floor were converted to 55,000 sq ft of retail space.[18] A huge atrium was cut into the lobby[19] and escalators were installed leading to an underground shopping area and food court. The parking garage adjacent to the hotel had a 70,000 sq ft fitness club[17] built on top of it to serve the complex. The hotel rooms on floors 3 to 11 were converted into 280,000 sq ft of office space,[18] entered through the original main entrance facing Broad Street, with the office portion opening on December 5, 1988.[17]

The hotel portion was condensed to 170 guest rooms on floors 12-18. The hotel was entered through a small foyer on the ground floor facing Chancellor Court, with the lobby and public rooms on the remodeled 19th floor. The two domed ballrooms on that floor (the South and North Cameo rooms), were turned into the Ethel Barrymore Tea Room and a restaurant called Founders, with statues of Philadelphia fathers William Penn, Benjamin Franklin, David Rittenhouse, and Charles Wilson Peale.[20] The middle wing of the E-shaped building[20] was removed from the guest room floors 12 to 18, and the back side was sealed up, creating an atrium. The historic 19th-floor Rose Ballroom atop this middle wing was retained, however, standing on seven-story stilts which ran through the atrium.[17]

The hotel portion reopened on April 1, 1989,[21] as the Hotel Atop The Bellevue, managed under a 10-year lease by the Cunard Line,[22] The hotel opened to protests by unionized former employees, because Cunard was not part of the agreement to rehire them and had not done so.[23] Cunard's hotel division proved financially unsuccessful and soon folded. Cunard terminated its lease on the hotel on February 7, 1993.[22] Interstate Hotels & Resorts of Pittsburgh assumed management in December 1994[24] and the hotel's name was shortened to match the whole multi-use complex, becoming The Bellevue. On December 1, 1996[24] Hyatt took over management of the hotel, placing it in their Park Hyatt boutique division and renaming it the Park Hyatt Philadelphia at the Bellevue. In 2007 the two restaurants and Founders bar were re-designed by Marguerite Rodgers as XIX (NINETEEN) Cafe, Bar and Restaurant. In 2009 all four balconies outside the cafe and restaurant were restored and opened to the public for the highest outside dining experience in the city. In 2010 the hotel was moved from the Park Hyatt to the Hyatt division and its name was shortened to Hyatt at The Bellevue. The hotel moved to The Unbound Collection division of Hyatt in March 2018, and was renamed The Bellevue Hotel.[25]

In 1993 the city moved its convention center from West Philadelphia to Center City, sparking a boom in hotel occupancy for the Bellevue and other hostelries for a popular facility that subsequently benefited from a major expansion.[26]

See also

Philadelphia portal

Philadelphia portal- National Register of Historic Places listings in Center City, Philadelphia

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on June 21, 2006. Retrieved June 30, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://archinect.com/forum/thread/59850383/the-bellevue-stratford-hotel-of-philadelphia

- https://books.google.com/books?id=d2KfBAAAQBAJ&lpg=PT98&ots=QUprFtsQUA&dq=hotelier%20Charles%20Todd&pg=PT98#v=onepage&q=hotelier%20Charles%20Todd&f=false

- https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/15/business/behind-monopoly-an-inventor-who-didnt-pass-go.html

- https://books.google.com/books?id=cO-yBAAAQBAJ&lpg=PA99&ots=W6QxiyPgL4&dq=October%2030%2C%201963%20jfk%20motorcade%20hotel&pg=PA99#v=onepage&q=October%2030,%201963%20jfk%20motorcade%20hotel&f=false

- "Legionnaire disease". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- "Bellevue Stratford Will Close Mounting Debts Are Blamed". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-01-23. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Legionnaires' Disease – a History of its Discovery" (January 16, 2003)

- Goldberg, Debbie (1986-01-27). "American Journal". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Detroit Free Press from Detroit, Michigan on September 9, 1979 · Page 41". Newspapers.com.

- "Western International returns Bellevue Stratford Hotel to Philadelphia". UPI.

- "New Plan For Bellevue Unveiled Shops, Offices To Be Added To The Hotel". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-02-12. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "The 'Grande Dame' Takes Early Retirement". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-03-07. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "The Final Days Of The Bellevue Debt Is Unwanted Guest On This Hotel's Register". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-01-29. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "The Bellevue Dies – Quietly – Today". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-03-07. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "New Look For An Old Landmark Bellevue Offices Will Open Today". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1988-12-05. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Philadelphia Hotel Is Facing 3d Revival". Chicago Tribune. 1988-10-08. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Inside Look A Makeover For The Historic Bellevue". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1988-03-06. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- Martin, Harold H. (1988-10-16). "The `Grand Old Lady' Of Broad Street". Deseret News. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Hotel Atop The Bellevue Tosses A Gala Former Employees Don't Get Rehired". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1986-02-11. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Luxury Hotel In Philadelphia Ends Its Ties With Cunard". Chicago Tribune. 1993-02-07. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Hotel Workers Set Bellevue Protest On Jobs". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1989-04-01. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "Bellevue Renamed The Park Hyatt The New Management Takes Over On Sunday. Investors Hope To Cash In On The Hyatt Cachet". Philadelphia Inquirer. 1996-11-27. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- "The Unbound Collection by Hyatt to Develop New Hotel in Hollywood, CA". www.hotelnewsresource.com.

- https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/convention-centers/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bellevue-Stratford Hotel. |

- The Bellevue – official building website

- The Bellevue Hotel – official website

- BBC Article about the search for the cause of Legionnaire's Disease

- The disaster that struck the Bellevue Stratford Hotel

- The Bellevue Memorabilia Collection, 1884–2005, including photographs, brochures, programs, drawings and other materials, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-1226, "Bellevue-Stratford Hotel"

- The application for the National Registry

- Listing at Philadelphia Architects and Buildings